The Chronicle Novel Op Compton Mackenzie 1937-1945 a Study Op the Four Winds Op Love

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

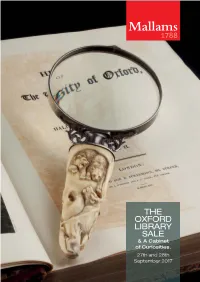

THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & a Cabinet of Curiosities

Mallams 1788 THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & A Cabinet of Curiosities. 27th and 28th September 2017 Chinese, Indian, Islamic & Japanese Art One of a pair of 25th & 26th October 2017 Chinese trade paintings, Final entries by September 27th 18th century £3000 – 4000 Included in the sale For more information please contact Robin Fisher on 01242 235712 or robin.fi[email protected] Mallams Auctioneers, Grosvenor Galleries, 26 Grosvenor Street Mallams Cheltenham GL52 2SG www.mallams.co.uk 1788 Jewellery & Silver A natural pearl, diamond and enamel brooch, with fitted Collingwood Ltd case Estimate £6000 - £8000 Wednesday 15th November 2017 Oxford Entries invited Closing date: 20th October 2017 For more information or to arrange a free valuation please contact: Louise Dennis FGA DGA E: [email protected] or T: 01865 241358 Mallams Auctioneers, Bocardo House, St Michael’s Street Mallams Oxford OX1 2EB www.mallams.co.uk 1788 BID IN THE SALEROOM Register at the front desk in advance of the auction, where you will receive a paddle number with which to bid. Take your seat in the saleroom and when you wish to bid, raide your paddle and catch the auctioneer’s attention. LEAVE A COMMISSION BID You may leave a commission bid via the website, by telephone, by email or in person at Mallams’ salerooms. Simply state the maximum price you would like to pay for a lot and we will purchase it for you at the lowest possible price, while taking the reserve price and other bids into account. BID OVER THE TELEPHONE Book a telephone line before the sale, stating which lots you would like to bid for, and we will call you in time for you to bid through one of our staff in the saleroom. -

Drinkers Order Whisky Galore Island's Entire Stocks … Five

Drinkers order Whisky Galore island’s entire stocks … five years too early 4th may 2009 shân ross Not a brick has been laid to build the first distillery on the island where Whisky Galore! was filmed—but connoisseurs have already signed up to reserve the entire batch of its first-year casks. Peter Brown will begin building the distillery on Barra in the autumn. The distillery, costing more than £1 million, will make about 5,000 gallons of Isle of Barra Single Malt Whisky a year using water from Loch Uisge, the island’s highest loch. It will use barley grown by crofters on the island before being milled and malted locally and be bottled at the distillery in Borve. Whisky needs to be matured for three years before it can legally be called whisky so the distillery will not have its first consignment until 2014. In the meantime Mr Brown has taken orders for the £1,000 oak casks from individuals and groups of friends from countries including Germany, Japan and Sweden, and the rest of the u.k. More than half the casks will be retained by the distillery but he is already selling his public quota of second-year reserve. Mr Brown said it was impossible to tell at this stage what the whisky would taste like but that it was ‘unlikely to be excessively peaty’. He said it would sell at about £30 a bottle at current prices at the premium end of market. Mr Brown, who ran a courier company in Edinburgh before moving to Barra 12 years ago, said: ‘The whisky will be of the island, from the island. -

The Rat Pack and the British Pierrot

THE RAT PACK AND THE BRITISH PIERROT: NEGOTIATIONS OF NATIONAL IDENTITY, ALIENATION AND BELONGING IN THE AESTHETICS AND INFLUENCES OF CONCERTED TROUPES IN POPULAR ENTERTAINMENT. DAVE CALVERT A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Research The University of Huddersfield January 2013 Abstract The thesis below consists of an introduction followed by three chapters that reflect on the performance work of two distinct forms, the British Pierrot troupe and the Rat Pack. The former is a model of performance adopted and adapted by several hundred companies around the British coastline in the first half of the twentieth century. The latter is an exclusive collaboration between five performers with celebrated individual careers in post-World War Two America. Both are indebted to the rise of blackface minstrelsy, and the subsequent traditions of variety or vaudeville performance. Both are also concerned with matters of national unity, alienation and belonging. The Introduction will expand on the two forms, and the similarities and differences between them. While these broad similarities lend a thematic framework to the thesis, the distinctions are marked and specific. Accordingly, the chapters are discrete and do not directly inform or refer to each other. Chapter One considers the emergence of the Pierrot troupe from a historical European aesthetic and argues that despite references to earlier Italian and French modes of performance, the innovations of the new form situate the British Pierrot in its contemporary and domestic context. Chapter Two explores this context in more detail, and looks at the Pierrot’s place in a symbolic network that encompasses royal imagery and identity, the racial implications of blackface minstrelsy and the carnivalesque liminality of the seaside. -

Memories of Pitsford a 100 Years Ago

49 MEMORIES OF PITSFORD A HUNDRED YEARS AGO T. G. TUCKER Introduction by the late Joan Wake* All my life I had heard of the clever Pitsford boy, Tom Tucker-whose name was a legend in the Wake family. I knew he had emigrated to Australia a.s a young man and I had therefore never expected to see him in the flesh-when all of a sudden in the middle of my third war-he turned up! This was in 1941. He got into touch with my aunt, Miss Lucy Wake, who had known him as a boy, and through her I invited him to come and stay with me for a few days in my little house at Cosgrove. He was then a good-looking, white haired old gentleman, of marked refinement, and of course highly cultivated, and over eighty years of age. He was very communicative, and I much enjoyed his visit. Tom's father was coachman, first to my great-great-aunt Louisa, Lady Sitwell, at Hunter- combe near Maidenhead in Berkshire, and then to her sister, my great-grandmother, Charlotte, Lady Wake, at Pitsford. Tom described to me the two days' journey in the furniture van from one place to the other-stopping the night at Newport Pagnell, and the struggle of the horses up Boughton hill, slippery with ice, as they neared the end of their journey. That must have been in 1868 or 1869. He was then about eight years of age. My great-grandmother took a great interest in him after discovering that he was the cleverest boy in the village, and he told me that he owed everything to her. -

Beautiful, Spacious Beachside Island Home

Beautiful, Spacious Beachside Island Home Suidheachan, Eoligarry, Isle of Barra, HS9 5YD Entrance hallway • Kitchen • Dining room • Utility room Drawing room / games room • Sitting room • Inner hallway • Bathroom Master bedroom with en suite 4 further bedrooms • Butler’s pantry • Shower room Bedroom 5 / study Directions The isle of Barra is often If you are taking the ferry from described as the jewel of the Oban you will arrive at Castle Hebrides with its spectacular Bay – turn right and continue beaches, rugged landscaped north for approximately 8.3 and flower laden machair, while miles; Suidheachan is on the the wildlife rich isles of left hand side adjacent to Vatersay (linked by a causeway Barra Airport. to Barra) and Mingulay (accessed by boat) are equally If flying to Barra Airport – stunning and also boast idyllic Suidheachan is adjacent to beaches. The beaches in Barra the airport. and Vatersay are among the very best in the world with Flights to Barra Airport from fabulously white sands and Glasgow Airport take around 1 crystal clear waters. The hour 10 minutes in normal beaches offer large and empty flying conditions. The ferry stretches of perfect sand and from Oban takes are also popular with sea approximately 4 hours 30 kayakers and surfers. The minutes in normal wildlife on the island is sailing conditions. stunning, with numerous opportunities for wildlife Situation watching including seals, The beautiful isle of Barra is a golden eagles, puffins, 23 square mile island located guillemots and kittiwakes, with approximately 80 miles from oyster catchers and plovers on the mainland reached by either the seashore. -

David Lodge's Campus Fiction

UNIVERSITY OF UMEÅ DISSERTATION ISSN 0345-0155 — ISBN 91-7174-831-8 From the Department of English, Faculty of Humanities, University of Umeå, Sweden. CAMPUS CLOWNS AND THE CANON DAVID LODGE’S CAMPUS FICTION AN ACADEMIC DISSERTATION which will, on the proper authority of the Chancellor’s Office of Umeå University for passing the doctoral examination, be publicly defended in Hörsal G, Humanisthuset, on Saturday, December 18, at 10 a.m. Eva Lambertsson Björk University of Umeå Umeå 1993 Lambertsson Björk, Eva: Campus Clowns and the Canon: David Lodge's Campus Fiction. Monograph 1993,139 pp. Department of English, University of Umeå, S-901 87 Umeå, Sweden. Acta Universitatis Umensis. Umeå Studies in the Humanities 115. ISSN 0345-0155 ISBN 91-7174-831-8 Distributed by Almqvist & Wiksell International P.O. Box 4627, S-116 91 Stockholm, Sweden. ABSTRACT This is a study of David Lodge's campus novels: The British Museum is Falling Down, Changing Places , Small World and Nice Work. Unlike most previous studies of Lodge's work, which have focussed on literary-theoretical issues, this dissertation aims at unravelling some of the ideological impulses that inform his campus fiction. A basic assumption of this study is that literature is never disinterested; it is always an ideological statement about the world. Mikhail Bakhtin's concept of the dialogical relationship between self and other provides a means of investigating the interaction between author and reader; central to this project is Bakhtin’s notion of how to reach an independent, ideological consciousness through the active scrutiny of the authoritative discourses surrounding us. -

Two Gentlemen of Verona

39th Season • 378th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / FEBRUARY 21 THROUGH MARCH 30, 2003 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design DARCY SCANLIN JOYCE KIM LEE GEOFF KORF Composer/Sound Design Vocal Consultant Production Manager Stage Manager ARAM ARSLANIAN URSULA MEYER JEFF GIFFORD *SCOTT HARRISON Directed by MARK RUCKER Honorary Producers HASKELL & WHITE, LLP Two Gentlemen of Verona • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Valentine ................................................................................. *Gregory Crane Proteus .......................................................................................... *Scott Soren Speed, a servant to Valentine ............................................. *Daniel T. Parker Julia, beloved of Proteus ................................................... *Jennifer Elise Cox Lucetta, waiting woman to Julia ...................................... *Rachel Dara Wolfe Antonio, father to Proteus .............................................................. *Don Took Panthino, a servant to Antonio .............................................. *Hal Landon Jr. Silvia, beloved of Valentine ....................................................... *Nealy Glenn Launce, a servant to Proteus .................................................... *Travis Vaden Thurio, a rival to Valentine .................................................. *Guilford -

Women's University Fiction, 1880-1945

Alberta Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 61.2, Summer 2015, 250-254 Book Review Women’s University Fiction, 1880-1945 Anna Bogen London: Pickering & Chatto, 2014 Reviewed by: Jennifer Helgren University of the Pacific In Women’s University Fiction, 1880-1945, Anna Bogen sets out to challenge interpretations of women’s university fiction as flat or failed. Her sophisticated literary analysis of early 20th- century university fiction, or coming-of-age fiction within the Oxbridge (University of Oxford in Oxford, England, and University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England) setting, adds to our understanding of women’s place in the university and demonstrates how gender affects genre. Bogen sees university fiction as a particular subgenre of Bildungsroman in which the main character reaches self-realization and an independent subject position through education. Comparing men’s and women’s novels, Bogen argues that women’s exclusion from the center of university life made it difficult for women authors to comfortably fit their narratives into the traditional Bildungsroman structure. However, rather than jettison the genre, women authors used it to expose women’s marginality in the university and in the process, exposed the genre’s tensions. Bogen’s texts include those that received critical analyses, such as Compton Mackenzie’s foundational Sinister Street (1913), Virginia Woolf’s “A Woman’s College from the Outside” (1926), and Rosamond Lehmann’s Dusty Answer (1927) as well as texts that many critics ignored. Bogen’s book complements Elaine Showalter’s Faculty Towers: The Academic Novel and Its Discontents (2005), an examination of university fiction after World War II, but it is the first sustained analysis of early 20th-century women’s university fiction in England. -

Northamptonshire Past & Present

~nqirnt and MODERN .... large or small. Fine building is synonymous with Robert Marriott Ltd., a member of the Robert Marriott Group, famous for quality building since 1890. In the past 80 years Marriotts have established a reputation for meticulous craftsmanship on the largest and small est scales. Whether it is a £7,000,000 housing contract near Bletchley, a new head quarters for Buckinghamshire County Council at Aylesbury (right) or restor ation and alterations to Easton Maudit Church (left) Marriotts have the experi ence, the expertise and the men to carry out work of the most exacting standards and to a strict schedule. In the last century Marriotts made a name for itself by the skill of its crafts men employed on restoring buildings of great historical importance. A re markable tribute to the firm's founder, the late Mr. Robert Marriott was paid in 1948 by Sir Albert Richardson, later President of the Royal Academy, when he said: "He was a master builder of the calibre of the Grimbolds and other famous country men. He spared no pains and placed ultimate good before financial gain. No mean craftsman him self, he demanded similar excellence from his helpers." Three-quarters of a century later Marriotts' highly specialised Special Projects Division displays the same inherent skills in the same delicate work on buildings throughout the Midlands. To date Hatfield House, Long Melford Hall in Suffolk, the Branch Library at Earls Barton, the restoration of Castle Cottage at Higham Ferrers, Fisons Ltd., Cambridge, Greens Norton School, Woburn Abbey restorations and the Falcon Inn, Castle Ashby, all bear witness to the craftsmanship of Marriotts. -

Now Whisky Galore Isle to Build Its Own £2.5M Distillery

Source: Scottish Daily Mail {Main} Edition: Country: UK Date: Tuesday 29, January 2019 Page: 28 Area: 125 sq. cm Circulation: 90121 Daily Ad data: page rate £5,040.00, scc rate £20.00 Phone: Keyword: Barra Distillery Now Whisky Galore isle to build its own £2.5m distillery Daily Mail Reporter in cases when it ran aground in 1941. The crew were rescued IT was once the island home unharmed. of Whisky Galore author Sir Sir Compton’s 1947 novel inspired the 1949 Ealing comedy Compton Mackenzie. Barra in the Outer Hebrides in which many islanders were used as extras. was also used in making the classic film of his book, which Barra Distillery director Peter was based on the true-life Brown said: ‘You cannot buy the grounding of the SS Politician publicity that the mere hint of with a cargo of the spirit on the Whisky Galore gives.’ neighbouring island of Eriskay. Now it is hoped there really ‘Environmentally will be whisky galore on Barra friendly’ after the launch of a shares offer for a £2.5million distillery project. It is looking for £1.5million of the cash through crowdfunding. The scheme, which already has planning permission for a site above the township of Borve, aims to be the ‘most environmentally friendly whisky distillery’ in the UK. Four wind turbines have already been built. Two hydro turbines as well as solar panels will be added to meet all energy requirements. The distillery will use the peaty water from the island reservoir at Loch Uisge. It is hoped to secure a local supply of barley, grown in Barra or neighbouring Uist. -

Stratford-Upon-Avoh Festival

A H A N D BOO K TO THE STRATFO RD - U PON - AVON FESTIVAL A Handb o o k to the St rat fo rd- u p o n- A V O H Fe st iv al WITH ART I C LE S BY N R . B N O F . E S ARTHUR HUTCHINSO N N R EG I A L D R . B UC K L EY CECI L SH RP J. A A ND [ LL USTRA TI ONS P UBLI SHED UNDER TH E A USPICES A ND WITH THE SPECIAL SANCTION OF TH E SHAKESPEARE M EMORIAL COUNCI L LONDON NY L GEO RGE ALLEN COM PA , T D. 44 45 RATH B ONE P LA CE I 9 1 3 [All rig hts reserved] P rinted b y A L L A NT Y NE A NSON ér' B , H Co . A t the Ballant ne P ress y , Edinb urg h P R E F A IC E “ T H E Shakespeare Revival , published two years ago , has familiarised many with the ideas inseparable from any national dramatic Festival . But in that book one necessarily Opened up vistas of future development beyond the requirements of those who desire a Hand a book rather than Herald of the Future . For them an abridgment and revision are effected here . Also there are considerable additions , and Mr . Cecil J . Sharp contributes a chapter explaining the Vacation School of Folk Song o f and Dance , which he became Director since the previous volume was issued . The present volume is intended at once to supplement and no t condense , to supersede , the library edition . -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS The Rural Tradition: a Study of the Non-Fiction Prose Writers of the English Countryside. By W.J. Keith. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974. Pp. xiv, 310. $15.00. Thirteen years ago, a young university teacher and novelist enquired what I had done my recently completed Ph.D. dissertation on; and when I told him it was on George Sturt and English rural labouring life, he asked if 1 was joking. I could see why. On the face of it, writers like Sturt or Richard Jefferies - assuming one knew of them at all - were simply not the kind whose non-fiction about rural life demanded academic treatment. They wrote about relatively uncomplicated beings and doings, in lucid and unostentatious prose. There were no metaphysical depths to sound in them, no paradoxes to tease out, no striking historical obscurities to elucidate. Their works did not belong in any obvious genre, and there had been no significant critical controversies about them. Yet these very qualities could make such writers peculiarly interesting to work on if one was moved by them and wanted to find out why. 1n 1965, W.J. Keith gave us the first academic book on Richard Jefferies, based in part on an MA. thesis of his own. It was a very decent piece of work, unmarred by special pleading or a self-servingly ingenious discovery of non-existent complexities, and it was well calculated to get Jefferies taken seriously by readers ignorant of, or prejudiced against, the important review-article on hirp by Q.D. Leavis in Scrutiny (1938).