Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology Volume 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Rev. Tim Smith Receives Neighborhood Leader Award

Non-profit Organization U. S. Postage 5344 Second Avenue PAID Pittsburgh, PA Pittsburgh, PA 15207 Permit No. 5333 Volume 2, No. 6 June, 2014 PUBLISHED BY HAZELWOOD INITIATIVE, INC. 5344 SECOND AVENUE, PITTSBURGH, PA 15207 Rev. Tim Smith Receives Neighborhood Leader Award his own Shadyside neighborhood by divid- member of the Pittsburgh Rock ‘N Hall ing it into 17 zones and creating a program of Fame and cheered the 2014 Alderdice that could and has been replicated count- Dragons who won the City League Boys less times. He recently received national Basketball Championship. We heralded recognition as recipient of the Iron Eyes the renowned artist Robert L. Qualters Cody Award during Keep America Beauti- Jr. for his life’s work and recognized the ful’s National Conference. Boris literally 2014 Inductees into the Jewish Sports personifies CPC’s mission to improve the Hall of Fame. environmental quality of life of Pittsburgh Space precludes me from highlighting residents through litter and illegal dumping hundreds of other outstanding and dedi- prevention, clean-up and enforcement. cated volunteers who are so worthy of Our office presented a variety of proc- recognition for their many contributions lamations to individuals, organizations, to our neighborhoods, our city and our and athletic teams to recognize their con- region. I offer a sincere thank you to all tributions and talents. We congratulated the unsung volunteers who do so much to Rich Engler who was inducted as the first make Pittsburgh a special place. Rev. Tim Smith’s Achievements As L to R: Corey O’Connor, Aggie Brose-past President of PCRG, Tim Smith, Ernie Listed In The Awards Banquet Program Hogan-Executive Director of PCRG on the dais at the William Penn Hotel for the Tim Smith has devoted his life to communicate positive messages about PCRG Summit. -

Korean Women, K-Pop, and Fandom a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE K- Popping: Korean Women, K-Pop, and Fandom A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Jungwon Kim December 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Deborah Wong, Chairperson Dr. Kelly Y. Jeong Dr. René T.A. Lysloff Dr. Jonathan Ritter Copyright by Jungwon Kim 2017 The Dissertation of Jungwon Kim is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Without wonderful people who supported me throughout the course of my research, I would have been unable to finish this dissertation. I am deeply grateful to each of them. First, I want to express my most heartfelt gratitude to my advisor, Deborah Wong, who has been an amazing scholarly mentor as well as a model for living a humane life. Thanks to her encouragement in 2012, after I encountered her and gave her my portfolio at the SEM in New Orleans, I decided to pursue my doctorate at UCR in 2013. Thank you for continuously encouraging me to carry through my research project and earnestly giving me your critical advice and feedback on this dissertation. I would like to extend my warmest thanks to my dissertation committee members, Kelly Jeong, René Lysloff, and Jonathan Ritter. Through taking seminars and individual studies with these great faculty members at UCR, I gained my expertise in Korean studies, popular music studies, and ethnomusicology. Thank you for your essential and insightful suggestions on my work. My special acknowledgement goes to the Korean female K-pop fans who were willing to participate in my research. -

First Time Viagra User

K-pop Fans’ Reaction Videos and Their Implications for Korean Language Learning Soojin Ahn University of Seoul Abstract As social media platforms such as YouTube have become important access points for Korean popular music (K-pop), international fans have enjoyed recording and sharing their responses to K-pop music videos on social media. In particular, reaction videos have been the most convenient and popular way for many international fans to share their opinions on and reactions to K-pop songs with others. This study aims to investigate the unique characteristics of reaction videos to share K-pop fans’ cultural experiences through YouTube videos and discuss the potential use of such fans’ learner motivation and learning environment for Korean language education. Four YouTube reaction videos were investigated through thematic analysis and through a discourse analysis informed by interactional sociolinguistics. The findings show how the reaction video creators build a community with other fans by establishing familiarity through agreement, considering the audience, and exchanging information, not only about a specific song, but also about K-pop in general and Korean Wave genres. These creators also demonstrated multiliteracies by expressing their opinions and feelings through facial expressions, visuals, and dance. These creators make their reaction videos regularly, proving their long-term enthusiasm for K-pop and the Korean Wave. This research offers important implications for future Korean language education, which will embrace diverse groups of international learners who actively participate in K-pop fan activities online. Keywords: K-pop, Korean Wave, reaction video, Korean as a Foreign Language (KFL), learner motivation, learner autonomy Introduction Since the early 2010s, Korean popular music (K-pop) has enjoyed popularity among increasing numbers of international fans in Asia, Europe, and North America. -

December-January 2015

Page 1 December 2014/January 2015 PCCC’s VISIONS Volume XLIII Issue 2 The Student Newspaper of Passaic County Community College, Paterson, NJ December 2014/January 2015 Human trafficking in our own backyard By Mahmuda Alam Although we believe slavery end- iarity with surroundings, laws and rights, ed in the U.S. in 1865, human trafficking language fluency, and cultural under- is still going on around the globe. Human standing. trafficking is a form of modern-day slav- Human trafficking is a mar- ery in which traffickers use force, fraud, ket-driven criminal industry that is based manipulation and/or coercion to control on the principles of supply and demand, the victims and gain profit from their like drugs or arms trafficking. Many fac- work. They use violence, threats, decep- tors make children and adults vulnerable tion, debt, bondage and other manipula- to human trafficking; however, it does not tive tactics to trap the victim in horrific exist because people are vulnerable to situations in America. All these victims exploitation. Instead, human trafficking share one common experience – the loss is operated by a demand for cheap labor, of freedom. services and commercial sex. There are two types of human traf- As stated by Polaris Project, an- ficking: sex trafficking (commercial sex) nually, human traffickers produce billions and labor trafficking (labor/services). In of dollars in profits by victimizing mil- the United States, sex trafficking usually lions of people in the U.S. and around the happens in online escort services, residen- world. Traffickers are estimated to exploit tial brothels, brothels disguised as mas- tions and this is one of the reasons why PCCC 20.9 million victims, with an estimated sage businesses or spas, and in street prostitution. -

Korean Vocabulary Quiz Workbook O Fastest Way to Learn Over 1,000 + Words & Expressions Learn Over 400 Korean Words with Exciting Practice Exercises R E A

Based in Seoul and Denver, NEW AMPERSAND PUBLISHING was founded in 2016. With the lofty vision of “Connecting The World Through Literature”, we are one of the few COPYRIGHT INQURIES companies that specialize in publishing Korea-related titles in languages other than Korean. [email protected] It is our mission to cater to the needs of readers around the world, by breaking into previously VOLUME ORDERS unexplored markets with universally popular topics about Korea using dedicated brands – [email protected] including the hugely popular K-POP (under Fandom Media), Korean Study (under Bridge Education), Korean Culture, as well as Korean Classic Literature. With the rapidly-growing popularity of Korean Wave, or Hallyu, we understand that there is an imbalance between customers’ demand and the number of titles supplied, which can be translated into a huge growth potential. Many of our titles have already made a splash around the world. Our leading title, The KPOP Dictionary, has been Amazon.com’s best seller in multiple categories since its release back in 2016, with the overall sales rank as high as #840, among tens of millions of books available on the site. It’s also well received in markets outside North America, including the UK and other EU nations. Of course, other K-POP titles and Korean Study titles have a strong presence and are making a huge impact as well. In the coming years, we aim to expand and diversify our portfolio by collaborating with celebrities, Korean entertainment companies, and establishing partnerships with government organizations who can further provide us with more unique and attractive content for international readers. -

Board of Works to Be Formed the New Mayor

THE CHATHAM PRESS VOL. XX. NO. 2 CHATHAM, MORRIS CQUNTYr N; J.f JANUARY 8, '19UT PRICE, iTVE CENTS which should be replaced with new as Jeremiah C. White, a Democrat, for BOARD OF WORKS soon as possible. The report was ac- THE NEW MAYOR many years, was abolished, and J. THE HOME AND SCHOOL ASSOCIATION cepted and filed. • Fred Runyon was elected clerk of com- A tentative budget of $17,000, the mittees at a salary of $100 a month. TO BE FORMED same as last year, was adopted, which ' IS SWORN IN His predecessor received $75. It was LOOK—REMEMBER. their eyes as they come In sight of budget will be revised, downward we stated tliat Mr. Runyou muBt give his the home-place. hope, when the various committees An Ordinance Providing for F. L. Auble To SUC* time to the work, audit all bills sub- Dr. Florence Richards will speak at If this is the worth-while-thing In have made their estimates of the mitted, ami keep track of things In the Public School Auditorium this Sat- life, home-dwellers must train the Such a Body Introduced at amounts to be expended during the Ceed Him HS a Member general. urday afternoon, January 8th, at 2.30 young for home-making; boys for year. The present budget is made up the Council Meeting A tentative budget of $450,175 was o'clock,. Admission free to all mothers fatherhood and girls for maternity. It of the following amounts: Roads, LIST OF APPOINTMENTS^.,lopted as against $505,000 for 1916. -

Lng·HAM YNEWS L 12 PAGES

If yoa sccl( a delightful· pcnimula, loolj about you. 1 A great city i.~ a gmH ]: , -Motto of M chlgan. solitude; a little city yiclcl.v l great friends,,: ' lNG·HAM YNEWS l 12 PAGES. NO MIN A'rED FOR MAYOR J~WETT ~HO~fN MAYOR, INOIIAI~( IS }rfllll'll IN A~IOUNT OF OASII RJDCElVED, OI'~CNINO Olr IIUNTING SIDASON RfGAINS SfAT IS NICX'l' 'l'UESDAY, DOUBTS '1111AT REAL SANOl'IONS ~liNTON \VJlLL UE A!l'l'UED, ' ,J, A. UHOWER NO~rJNA'l'JIJO AS Army Of lluntorK AwrtUM Opening, JUS'l'IOE OF l'Et\OE. Scrt~on Bu.g Umll.!! Arc Clumgcll Olu.llns Ethllljlla llu.M UeBn European On ·PhOtloSun J,~. Prtwn For ntatny Yeur111 Conntry Ila&s Sllwlu: Value. Ulg Crowd Att~miH Caumu, Inetun· bcntl!i ltot.nln OlflcoM, .ll~M. Wttg"· Ethiopians scunylng for covor to goner Nnmod TreJILSIJrcr, esca.pe the bombing· of Signor Musso· lint's sky troops will havo the sym pathy of Michigan gamo birds next wcelt, The upland gamo season opens Tuesday morning, October 15, at sun rlso nnd continues until sundown on · October 27. Fox squirrels may be hunted until sundown of October 21 and ralls may be hunted until Novem ber 10. Tho·seasoJJ onrnbblts Is stag· gored, North of th!3 norlh line of 'l'own 1B tho season Is, open from Oc tober 15 to January 81; soutl1 of that line, the season closes January 1. Ga.me which may bu Jogully hunted In the lower peninsula next Tuesd~y Includes pheasants, ruffod grouse, prairie chlclten, sharp tailed grouse, fox squirrels, ralls, except coots, woodcock and rabbits, Season bug limits on several species of birds have been lnca·ensed over la.st year by the 1935 legislature. -

The Impact of the WPI PLAN on Students. a Report of a Three Year

18 Mr. fAhies 1,,,low show the numher students on the Plan and the number in fhadifional pro,;ram who tool,.the examination and either passed lyf from the data is that there was a sLafisri.illy ficAnt d111,,riecc hctt...t.en the s-ores ot thy Plan students who Ihe Plan i And the non-Plan students w11,, did likewise. AverAd 8 t. a. h thei sc ii s tfhis includes scures both Af fhose nased And wit, did a i,ass, Assn ,i,ht that tunics ho d d not pass received rain S;c., i.e., 65--fhe lioarJ would no m,lanert: whi i e the non-Pian students figured on a 1.era.ge sc)res of 8.37. W10 Look the examination, 887, passed (average score not AL WPI, the Plan students who Look the examination pat;sed and h At.terage passing score was 8 .8;for the non-Plan students, only pas'-ed tne xam and their average passing score was80.6. In hriet, no matter hot,one examines the data, itis readily apparent ngineering competency, there is no way that t1taf, an rht:-; part ( lar index ,i .)ne can say that tiw P1An studeats did notsurpass the non-Plan students to some extent. hi a indexis only one indicatP,n ot actual engineering competency,and many other factors ths: he Laken into account, manyprofessionals in the field r,,ard thy EIT test_ ic ores As sili,nificant. and "hard" datawhich indicates the This EIT result: then, points to the valueof value of -1 petf.*Aa a An en'f;i.neer. -

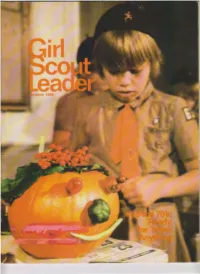

Who Pays What for Girl Scouting? H Ma an P a at O of the D Ne·E T • Ds of C G Ated Tog Is a D ·He R T Oops a D Os

irl ORDER N • Allow two to four ~· ' weeks for delivery. Calendars come • I) i ~ packed 100 to the 5 h carton and must be ordered by the carton. Min1mum order is one carton. \h - ,, H Unsaid calendars cannot be returned. 1! Orden from troops must be received '" by OC1ober 1 S 1969 to be auured of )) 2\ del1very \l) !0 -- _I,- 2~ 29 _,7* 26 QUANTITIES and PRICES Within the United States 100 to 1000 copies .. 17c each 11 00 to 2500 copies ... 16c each Please ship_ copies of the 1970 Girl Scout Calendar a t_ c each, 2600 to 5000 copies ... 15c each to arrive (date)__ ____ 5100 to 10000 copies ... 14c each 101 00 to 25000 copies ... 13c each 0 We agree to remit total amount 30 days after our sale. 25100 to 75000 copies ... 12c each 0 Enclosed is full payment of $ 75100 and over . 11 c each (00 NOT SENO PART/At PAYMENT Outside the continental United States We have permission from our council 0 ; our lone troop (i ncluding Alcuko one! Howoii committee 0 to hold a Calendar Sale. Each calendar ....... 20c prepaid NAME ......................................... ............. Calendar orders from lroopt on foreign STREET ......................................................... soil .and APO addreues mutt include full remittance-orders from thete troops will not be accepted aher October 1, 1969. CITY ...... .".............. ..... STATE .......... ZIP CODE ....... three reasons why Girl Scout NUT PRODUCTS WILL SELL FASTER THAN EVER BEFORE three md•v•dua vacuum packs 1n<ade one tJox Now, you can earn greater profits 1n less ttme Thrs new three pack has mstant customer appeal Many v.