Lessons from a Dialect Survey of Bena: Analysing Wordlists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Referred to As Class 18A (See Hyman 1980:187)

WS1 Remarks on the nasal classes in Mungbam and Naki Mungbam and Naki are two non-Grassfields Bantoid languages spoken along the northwest frontier of the Grassfields area to the north of the Ring languages. Until recently, they were poorly described, but new data reveals them to show significant nasal noun class patterns, some of which do not appear to have been previously noted for Bantoid. The key patterns are: 1. Like many other languages of their region (see Good et al. 2011), they make productive use of a mysterious diminutive plural prefix with a form like mu-, with associated concords in m, here referred to as Class 18a (see Hyman 1980:187). 2. The five dialects of Mungbam show a level of variation in their nasal classes that one might normally expect of distinct languages. a. Two dialects show no evidence for nasals in Class 6. Two other dialects, Munken and Ngun, show a Class 6 prefix on nouns of form a- but nasal concords. In Munken Class 6, this nasal is n, clearly distinct from an m associated with 6a; in Ngun, both 6 and 6a are associated with m concords. The Abar dialect shows a different pattern, with Class 6 nasal concords in m and nasal prefixes on some Class 6 nouns. b. The Abar, Biya, and Ngun dialects show a Class 18a prefix with form mN-, rather than the more regionally common mu-. This reduction is presumably connected to perseveratory nasalization attested throughout the languages of the region with a diachronic pathway along the lines of mu- > mũ- > mN- perhaps providing a partial example for the development of Bantu Class 9/10. -

Closed Adjective Classes and Primary Adjectives in African Languages Guillaume Segerer

Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages Guillaume Segerer To cite this version: Guillaume Segerer. Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages. 2008. halshs-00255943 HAL Id: halshs-00255943 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00255943 Preprint submitted on 14 Feb 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages Guillaume Segerer – LLACAN (INALCO, CNRS) Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages INTRODUCTION The existence of closed adjective classes (henceforth CAC) has long been recognized for African languages. Although I probably haven’t found the earliest mention of this property1, Welmers’ statement in African Language Structures is often quoted: “It is important to note, however, that in almost all Niger-Congo languages which have a class of adjectives, the class is rather small (...).” (Welmers 1973:250). Maurice Houis provides further precision: “Il y a lieu de noter que de nombreuses langues possèdent des lexèmes adjectivaux. Leur usage en discours est courant, toutefois l’inventaire est toujours limité (autour de 30 à 40 unités).” (Houis 1977:35). These two statements are not further developped by their respective authors. -

Contact N°177-178 About This Issue of Contact for Health

1 Contact n°177-178 About this issue of Contact for Health: Our lead topic is AIDS and malaria and we have From Uganda, Dr Pepper, a Southern Baptist Conven- received news from East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, and tion Missionary, physician and head of the HIV clinic, and Uganda; from Southern Africa and West Africa. internal medicine at the government teaching hospital MUTH, reports his practice of Biblical holistic care and The Ecumenical HIV/AIDS Initiative in Africa was his use of latest technologies: syringes where the launched in Nairobi. p.14 & 41 needle retracts after use. p.15 The Ecumenical Advocacy Alliance will be active in the The Safe Health Care and HIV coalition is petitioning 2004 IAS AIDS Conference in Bangkok. p.4 the 2004 World Health Assembly and proposing an amendment to insure total safety. p.42 “Africa could be depopulated by AIDS to an extent Coming together to confront AIDS, is the message of the not seen since Slavery!”, Reverend Dr. Samuel Kobia, The Inter Religious Council of Uganda received from General Secretary of the WCC, told Contact : “AIDS is Rev. Sam Lawrence Ruteikara, AIDS Director. p.15 the enemy”. p.5 The Church of the Province of West Africa, Anglican Special report TANZANIA (p.7-13) Provincial Health Service in Accra, Ghana, report that “In faith, we are breaking ground slowly”. p.16 “FAIR TRADE”, Tanzania’s Deputy Health Minister Hussein A. Mwinyi tells the world, “would best assist From the South African Catholic Bishops’ Conference Africa in meeting the challenge of HIV AIDS”. p.12 AIDS Office comes a call and a commitment for treat- ment. -

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

Community Concerns of Orphans and Development Association (Cocoda) P

COMMUNITY CONCERNS OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION (COCODA) P. O. BOX 712, NJOMBE - CHAUNGINGI STREET ALONG SONGEA ROAD, OPPOSITE TANESCO REGIONAL OFFICE Email: [email protected] Website: www.cocoda.or.tz COCODA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT COMMUNITY CONCERN OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION REPORTING PERIOD: 1 JANUARY – 31 DECEMBER 2019 Projects Implemented Councils • SAUTI Project Njombe Region councils: Njombe Town Council • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA Project • • Njombe District Council • USAID Tulonge Afya • Makambako Town Council • Makete District Council • Wanging’ombe District Council • Ludewa District Council Prime Recipients Implementing Partners • DELOITTE CONSULTANCY LTD • LGAs JHPIEGO • • Health facilities • PACT TANZANIA • FHI360 Programme/Project Budget/Year Programme Duration • SAUTI 182,970,583 5 Years • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA 297,158,227 5 Years • USAID TULONGE AFYA 159,376,560 5 Years TOTAL: 639,505,370 Report Submitted By o Name: Mary Kahemele o Title: Executive Director o Organization: COCODA o Email address: [email protected] o Phone No: 0754 071 288 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms / Abbreviations ................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ..................................................................................... 5 I. SAUTI PROJECT ................................................................................................. -

A Case of Kibena to Kimaswitule in Njombe District, Tanzania

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching ISSN: 2537 - 1754 ISSN-L: 2537 - 1754 Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/edu doi: 10.5281/zenodo.496189 Volume 2 │ Issue 2 │ 2017 SOCIAL FACTORS INFLUENCING LANGUAGE CHANGE: A CASE OF KIBENA TO KIMASWITULE IN NJOMBE DISTRICT, TANZANIA Leopard Jacob Mwalongoi The Northeast Normal University, 5268 Renmin Street, Changchin City, Post Code 130024, Jilin, China Abstract: The aim of the study was to examine the Language change from Kibena to Kimaswitule, specifically the study ought to identify social factors of Language change from Kibena to Kimaswitule; also to explore the impact of language change to the society. The study was done in Njombe District. The targeted population was the youth; the middle age and the elders (men and women) from Njombe district, below 15 years were not included in this study since they had little knowledge on the language change and shift from Kibena to Kimaswitule. 50 respondents were included in the study. The study used qualitative and quantitative approaches. The purposive and random sampling were used, the researcher predominantly used snowball sampling method to have sample for the study. Data were collected through, Focus Group Discussion (FGD), structured interview, questionnaire, observation and checklist methods. Data were analysed by scrutinizing, sorted, classified, coded and organized according to objectives of the study. The findings showed that, participant, personal needs, influence of other languages and development of towns are social factors for language change and the research concluded that, changes of Kibena to Kimaswitule has endangered the indigenous education of Wabena because change in the society goes hand in hand with the changes of the norms and values as language embeds culture. -

1 Parameters of Morpho-Syntactic Variation

This paper appeared in: Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 105:3 (2007) 253–338. Please always use the published version for citation. PARAMETERS OF MORPHO-SYNTACTIC VARIATION IN BANTU* a b c By LUTZ MARTEN , NANCY C. KULA AND NHLANHLA THWALA a School of Oriental and African Studies, b University of Leiden and School of Oriental and African Studies, c University of the Witwatersrand and School of Oriental and African Studies ABSTRACT Bantu languages are fairly uniform in terms of broad typological parameters. However, they have been noted to display a high degree or more fine-grained morpho-syntactic micro-variation. In this paper we develop a systematic approach to the study of morpho-syntactic variation in Bantu by developing 19 parameters which serve as the basis for cross-linguistic comparison and which we use for comparing ten south-eastern Bantu languages. We address conceptual issues involved in studying morpho-syntax along parametric lines and show how the data we have can be used for the quantitative study of language comparison. Although the work reported is a case study in need of expansion, we will show that it nevertheless produces relevant results. 1. INTRODUCTION Early studies of morphological and syntactic linguistic variation were mostly aimed at providing broad parameters according to which the languages of the world differ. The classification of languages into ‘inflectional’, ‘agglutinating’, and ‘isolating’ morphological types, originating from the work of Humboldt (1836), is a well-known example of this approach. Subsequent studies in linguistic typology, e.g. work following Greenberg (1963), similarly tried to formulate variables which could be applied to any language and which would classify languages into a number of different types. -

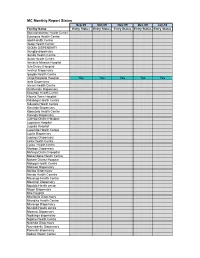

MC Monthly Report Status

MC Monthly Report Status Sep-09 Oct-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Jan-10 Facility Name Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Bomalang'ombe Health Centre Bulongwa Health Centre Idodi Health Centre Ifwagi Health Center IGOMA DISPENSARY Ihungilo dispensary Ikonda Health Centre Ikuwo Health Centre Ilembula Mission Hospital Ilula District Hospital Imalinyi Dispensary Ipogolo Health Centre Iringa Regional Hospital Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Isele Dispensary Ismani Health Centre Itulahumba Dispensary Kasanga Health Centre Kibena Town Hospital Kidabaga Health Centre Kidugala Health Centre Kimande Dispensary Kiponzelo Health Centre Kisanga Dispensary Ludewa District Hospital Lugalawa Hospital Lugoda Hospital Lupembe Health Centre Lupila Dispensary Lupingu Dispensary Lwila Health Centre Lyasa Health centre Madege Dispensary Mafinga District Hospital Makambako Health Centre Makete District Hospital Makoga Health Centre Makowo Dispensary Maliwa Dispensary Manda Health Ceantre Mavanga Health Centre Mawengi Dispensary Mgololo Health center Migori Dispensary Milo Hospital Mtambula Dispensary Mtandika Health Centre Mtwango Dispensary Mundidi Health centre Mwatasi Dispensary Ngalanga dispensary Ngome Health Centre Nyombo Dispensary Nyumbanitu Dispensary Pomerini dispensary Sadani Health Center Saint Lukes Dispensary Tanangozi Dispensary TANWAT Hospital Tosamaganga District Hospital Ugwachanya Dispensary Ujuni Dispensary Ukalawa dispensary Uliwa Dispensary Usokami HC Key: Not Applicable Available Not Available Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 May-10 Jun-10 Jul-10 -

Mkoa Wa Njombe Orodha Ya Wanafunzi Waliochaguliwa Kujiunga Na Shule Za Sekondari Kidato Cha Kwanza Januari 2021 A.Shule Za Bweni 1

MKOA WA NJOMBE ORODHA YA WANAFUNZI WALIOCHAGULIWA KUJIUNGA NA SHULE ZA SEKONDARI KIDATO CHA KWANZA JANUARI 2021 A.SHULE ZA BWENI 1. UFAULU MZURI (SPECIAL SCHOOLS) I. WAVULANA Na. NAMBA YA PREM JINA LA MWANAFUNZI SHULE ATOKAYO HALMASHAURI ILIPO SHULE AENDAYO 1 20141473414 EGAN GABRIEL NYUNJA MAMALILO LUDEWA DC KIBAHA 2 20143026593 DEUSDEDITH ADALBERT MGIMBA MAMALILO LUDEWA DC MZUMBE 3 20141421779 CLEVER KISWIGO MWAIKENDA ST.MONICA MAKETE DC MZUMBE 4 20140550889 FLOWIN VENANCE NGAILO SAINT MARYS' NJOMBE TC ILBORU 5 20141210886 MAKUNGANA ISDORY NYONI ST. BENEDICT NJOMBE TC KIBAHA 6 20141488623 GIDION HERMAN SHULI SIGRID MAKAMBAKO TC MZUMBE 7 20141488632 JOSEPH DAUD BEHILE SIGRID MAKAMBAKO TC KIBAHA 8 20140417413 OMEGA ADAMU KINYAMAGOHA IGIMA WANGING'OMBE DC ILBORU 9 20141421798 NASSAN CHRISTIAN KALINGA ST.MONICA MAKETE DC MZUMBE 10 20140821466 ABELINEGO FIDELIS MPONDA HAVANGA NJOMBE DC ILBORU 11 20140371530 KELVIN BEATUS MDZOVELA IGWACHANYA WANGING'OMBE DC ILBORU 2. SHULE ZA SEKONDARI UFUNDI Na. NAMBA YA PREM JINA LA MWANAFUNZI SHULE ATOKAYO HALMASHAURI ILIPO SHULE AENDAYO 1 20141210890 MARK - ERNEST ERNEST LUHANGANO ST. BENEDICT NJOMBE TC TANGA TECHNICAL 2 20141473370 BRIAN GABRIEL NYUNJA MAMALILO LUDEWA DC TANGA TECHNICAL 3 20141347868 ROBBY FRANK ILOMO UHURU MAKAMBAKO TC IFUNDA TECHNICAL 4 20140550884 ALPHA FAUSTINO MTITU SAINT MARYS' NJOMBE TC IFUNDA TECHNICAL 5 20141396387 MALIKI ALLY CHIEE MAMALILO LUDEWA DC TANGA TECHNICAL 6 20140156511 PETRO GODFRID MWALONGO MAMALILO LUDEWA DC IFUNDA TECHNICAL 7 20141488639 LOUIS NESTORY WILLA SIGRID -

The Oxford Guide to the Bantu Languages

submitted for The Oxford Guide to the Bantu Languages Bantu languages: Typology and variation Denis Creissels (3rd draft, August 12 2019) 1. Introduction With over 400 languages, the Bantu family provides an excellent empirical base for typological and comparative studies, and is particularly well suited to the study of microvariation (cf. Bloom & Petzell (this volume), Marlo (this volume)). This chapter provides an overview of the broad typological profile of Bantu languages, and of the major patterns and parameters of variation within the family. Inheritance from Proto-Bantu and uninterrupted contact between Bantu languages are certainly responsible for their relative typological homogeneity. It is however remarkable that the departures from the basic phonological and morphosyntactic structure inherited from Proto-Bantu are not equally distributed across the Bantu area. They are typically found in zone A, and to a lesser degree in (part of) zones B to D, resulting in a relatively high degree of typological diversity in this part of the Bantu area (often referred to as ‘Forest Bantu’), as opposed to the relative uniformity observed elsewhere (‘Savanna Bantu’). Typologically, Forest Bantu can be roughly characterized as intermediate between Savanna Bantu and the languages grouped with Narrow Bantu into the Southern Bantoid branch of Benue-Congo. Kiessling (this volume) provides an introduction to the West Ring languages of the Grassfields Bantu group, the closest relative of Narrow Bantu. Departures from the predominant typological profile -

The Inflectional Structure of Lubukusu Verbs Aggrey

i THE INFLECTIONAL STRUCTURE OF LUBUKUSU VERBS AGGREY WAFULA WATULO C50/NKU/CE/28191/2013 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER 2018 ii DECLARATION iii DEDICATION In memory of my dear late, mum Edith Nekoye, my late uncles Jeff Watulo and Fred Wenyaa for being my mentors. To my late grand mums Rosa and Rasoa who took good care of me after the demise of my mum. Lastly, to my dear wife Naomi who with unwavering support took good care of our lovely sons Ken and Mike while I was busy connecting dots during mid night and day time to make my writing scholarly. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT With a lot of humility, I appreciate our Almighty God for enriching me with sufficient grace and patience until this moment. I would not have travelled this long journey had it not been for God‟s mercy and guidance in all the activities I carried out in building my research work. My project has finally come to a success because of Dr. Nandelenga‟s dedication to read the many drafts I send to him. I am deeply indebted to Dr. Nandelenga‟s passionate guidance and advice during the time I was struggling to read and write my work. My profound gratitude goes to my linguistics MA lecturers whom I met during my course work. To Dr. Kirigia, Prof. Khasandi and Dr. Wathika thank you for taking me through course work. -

United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania The United Republic of Tanzania Jointly prepared by Ministry of Finance and Planning, National Bureau of Statistics and Njombe Regional Secretariat Njombe Region National Bureau of Statistics Njombe Dodoma November, 2020 Njombe Region Socio-Economic Profile, 2018 Foreword The goals of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025 are in line with United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and are pursued through the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) or MKUKUTA II. The major goals are to achieve a high-quality livelihood for the people, attain good governance through the rule of law and develop a strong and competitive economy. To monitor the progress in achieving these goals, there is need for timely, accurate data and information at all levels. Problems especially in rural areas are many and demanding. Social and economic services require sustainable improvement. The high primary school enrolment rates recently attained have to be maintained and so is the policy of making sure that all pupils who passed Primary School Leaving Examination must join form one. The Nutrition situation is still precarious; infant and maternal mortality rates continue to be high and unemployment triggers mass migration of youths from rural areas to the already overcrowded urban centres. Added to the above problems, is the menace posed by HIV/AIDS, the prevalence of which hinders efforts to advance into the 21st century of science and technology. The pandemic has been quite severe among the economically active population leaving in its wake an increasing number of orphans, broken families and much suffering. AIDS together with environmental deterioration are problems which cannot be ignored.