The New York Times and the Memory of the 1956 Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Visionary: John F. Kennedy's Life and Times

American Visionary: John F. Kennedy’s Life and Times Organized by Wiener Schiller Productions in collaboration with the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Curated by Lawrence Schiller Project Coordinator: Susan Bloom All images are 11 x 14 inches All frames are 17 x 20 inches 1.1 The Making of JFK John “Jack” Fitzgerald Kennedy at Nantasket Beach, Massachusetts, circa 1918. Photographer unknown (Corbis/Getty Images) The still-growing Kennedy family spent summers in Hull, Massachusetts on the Boston Harbor up to the mid-1920s, before establishing the family compound in Hyannis Port. 1.2 The Making of JFK A young Jack in the ocean, his father nearby, early 1920s. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Library Foundation) Kennedy’s young life was punctuated with bouts of illness, but he was seen by his teachers as a tenacious boy who played hard. He developed a great love of reading early, with a special interest in British and European history. 1.3 The Making of JFK Joseph Kennedy with sons Jack (left) and Joseph Patrick Jr., Brookline, Massachusetts, 1919. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Library Foundation) In 1919 Joe Kennedy began his career as stockbroker, following a position as bank president which he assumed in 1913 at age twenty-five. By 1935, his wealth had grown to $180 million; the equivalent to just over $3 billion today. Page 1 Updated 3/7/17 1.4 The Making of JFK The Kennedy children, June, 1926. Photographer Unknown (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum) Left to right: Joe Jr., Jack, Rose Marie, Kathleen, and Eunice, taken the year Joe Kennedy Sr. -

Marijuana-Correspondence.Pdf

Bobbie Walthall From: Peetu PuppyDog <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, March 19, 2019 11:57 AM To: Bobbie Walthall; Lisa Larsen; Matthew Herbert; Jennifer Ananda; Leslie Soden; Stuart Boley Cc: Patrick Wilbur; Tresa McAlhaney; Kirsten Kuhn Subject: Marijuana Ordinance Draft 031919 Some notes I have on the draft ordinance: 1. The second conviction doesn’t need to be $200 plus an evaluation – This seems excessive, there are no ordinances where the second conviction is 200 times worse than the first. The second should also be $1. 2. The age limit needs to be 18 because the higher education act drug provision is still in effect - denying or delaying financial aid for college students who are convicted in state or federal court of a drug-related offense. 3. We should remove the paragraph about the evaluation. If you are convicted in municipal court of battery while drunk, or open container, or consuming alcohol in public you are not required to get a drug & alcohol evaluation, why should we give an otherwise law-abiding citizen an evaluation for possessing marijuana without another serious offense, like driving under the influence? The judge can order an evaluation at any time. I would like to comment on the Lawrence paraphernalia ordinance. I spoke with Maria Garcia yesterday, and she confirmed that is possible to lower the fine from $200 to $1. I think this is wise. It doesn’t make sense to fine someone $1 for marijuana and $200 for a pipe. If someone is found with crack cocaine and a pipe, they would be charged in district court because it’s a felony drug charge. -

The National Film Preserve Ltd. Presents the This Festival Is Dedicated To

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE THIS FESTIVAL IS DEDICATED TO Stanley Kauffmann 1916–2013 Peter O’Toole 1932–2013 THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE Julie Huntsinger | Directors Tom Luddy Kim Morgan | Guest Directors Guy Maddin Gary Meyer | Senior Curator Mara Fortes | Curator Kirsten Laursen | Chief of Staff Brandt Garber | Production Manager Karen Schwartzman | SVP, Partnerships Erika Moss Gordon | VP, Filmanthropy & Education Melissa DeMicco | Development Manager Joanna Lyons | Events Manager Bärbel Hacke | Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell | VP, Publicity Justin Bradshaw | Media Manager Jannette Angelle Bivona | Executive Assistant Marc McDonald | Theater Operations Manager Lucy Lerner | SHOWCorps Manager Erica Gioga | Housing/Travel Manager Beth Calderello | Operations Manager Chapin Cutler | Technical Director Ross Krantz | Technical Wizard Barbara Grassia | Projection and Inspection Annette Insdorf | Moderator Mark Danner | Resident Curators Pierre Rissient Peter Sellars Paolo Cherchi Usai Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Chief Writer Larry Gross (LG) Prized Program Contributors Sheerly Avni (SA), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Jesse Dubus (JD), Geoff Dyer (GD), Gian Luca Farinelli (GLF), Mara Fortes (MF), Scott Foundas (SF), Guy Maddin (GM), Leonard Maltin (LM), Jonathan Marlow (JM), Todd McCarthy (TM), Gary Meyer (GaM), Kim Morgan (KM), Errol Morris (EM), David Thomson (DT), Peter von Bagh (PvB) Tribute Curator Short Films Curators Student Prints Curator Chris Robinson Jonathan Marlow Gregory Nava and Bill Pence 1 Guest Directors Sponsored by Audible.com The National Film Preserve, Ltd. Each year, Telluride’s Guest Director serves as a key collaborator in the A Colorado 501(c)(3) nonprofit, tax-exempt educational corporation Festival’s programming decisions, bringing new ideas and overlooked films. -

TCU DAILY SKIFF the Mid 50* and the High in the Upper 70S TCU DAILY SKIFF, THURSDAY

Dow tones Stocks WeatHet Today's weather will be partly cloudy and warm with the low in TCU DAILY SKIFF the mid 50* and the high in the upper 70s TCU DAILY SKIFF, THURSDAY. MARCH 11,1982 Senators draft No vote taken budget version on House bill WASHINGTON (API - Senate said Reagan "didn't rule out any something bad In be done to Republicans hope to finish drafting possibility. He did not embrace Btiy By USA ixr/lKH eliminate those not fulfdliug their an alternative to President Reagan's change It's clear to me that he's Staff Writer duties red-ink budget by next week, saying willing to consider any reasonable "We were elected to represent they are convinced he will consider suggestions that we make. I don't Alter debate failed to bring certain dorms and orca m/.limits.'' revisions. doubt that he's still fully committed agreement, the Student House of Monge said, "and we base a David R. Gergen, Reagan's to his defense numbers and to his tax Representatives Tuesday sent an responsibility to the House If we assistant for communications, said plan. Rut [ think nothing is off absenteeism bill back to committee. don! want hi attend meetings uyr the president was advised during limits." The Flections and Regulations shouldn't take the responsibilits ." meetings Tuesday to "take his case to After Reagan's visit Tuesday, Baker CommlttW will reconsider the lull, Representative Mark BaUheltlrr the country." and other key GOP senators held which proposes new measures tor said he fell current pro^ttlures ol Work on alternatives to Reagan's their second meeting of the week m a dealing with representative ab- excusing mentliers who Bjntff) IIK* big-deficit 1983 budget picked up continuing effort to pare a list of senteeism I rom House meetings president lielorehand should not lie steam after upbeat Capitol Hill possible changes in Reagan's budget Under the proposed bill, all ab- altered. -

Publications Editor Prized Program Contributors

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE Julie Huntsinger | Directors Tom Luddy Gary Meyer Muffy Deslaurier | Director of Support Services Brandt Garber | Production Manager Karen Schwartzman | SVP, Partnerships Erika Moss Gordon | VP, Filmanthropy Melissa DeMicco | Development Manager Jannette Angelle Bivona | Assistant to the Directors Kate Sibley | Education Programs Dean Jenny Jacobi | Operations Manager Joanna Lyons | Events Manager Bärbel Hacke | Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell | VP, Publicity Marc McDonald | Theater Operations Manager Lucy Lerner | SHOWCorps Manager Erica Gioga | Housing/Travel Manager Chapin Cutler | Technical Director Ross Krantz | Technical Wizard Barbara Grassia | Projection Chief Annette Insdorf | Moderator Mark Danner | Resident Curators Godfrey Reggio Pierre Rissient Peter Sellars Paolo Cherchi Usai Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Chief Writer Larry Gross (LG) Prized Program Contributors Sheerly Avni (SA), Michael Barker (MB), Meredith Brody (MBr), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Mark Danner (MD), Jesse Dubus (JD), Roger Ebert (RE), Scott Foundas (SF), Barry Jenkins (BJ), Dorna Khazeni (DK), Jonathan Marlow (JM), Todd McCarthy (TM), Colin MacCabe (CM), Gary Meyer (GM), Peter Sellars (PS), Milos Stehlik (MS), David Thomson (DT), Angela Valles (AV) Tribute Curator Short Films Curators Chris Robinson Barry Jenkins and Godfrey Reggio 1 Shows The National Film Preserve, Ltd. Introducing A Colorado 501(c)(3) nonprofit, tax-exempt educational corporation THE WERNER HERZOG THEATER Founded in 1974 by James Card, Tom Luddy and Bill & Stella Pence Directors Emeriti Bill & Stella Pence Board of Governors Peter Becker, Ken Burns, Peggy Curran, Michael Fitzgerald, Julie Huntsinger, Linda Lichter, Tom Luddy, Gary Meyer, Elizabeth Redleaf, Milos Stehlik, Shelton g. Stanfill (Chair), Joseph Steinberg Esteemed Council of Advisors Laurie Anderson | New York, NY Werner at TFF 7, 1980 Jeremy Barber | Los Angeles, CA Chuck Jones represents cinema’s joie de vivre, Abel Gance its vision and Alberto Barbera | Torino, Italy ingenuity. -

CREES NEWSLETTER the Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies

SPRING 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS CREES NEWSLETTER The Center for Russian, East European & Eurasian Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS _____________________________ From the Director CREES in Action Director’s Letter Hosting Civic Educators and Leaders from Georgia U.S. Russia Foundation Grant First Annual World Languages Fair Pages 2-3 Welcome to New REES M.A. Student Meet our Rising Stars and New Faculty Affiliate Fulbright Scholar Alexander Zhidchenko Pages 10-13 Laura Searcy, Fulbright ETA in Uzbekistan Pages 4-7 Our Community Faculty News and Updates In Memoriam Student and Alumni News BG John Reppert Become a CREES Donor Kenneth L. Smock Pages 14-16 Pages 8-9 CREES Team From the Director... It is my pleasure to wel- Director Vitaly Chernetsky come you back to a new Spring semester! We begin Assistant Director this new year with excit- Justyna Beinek ing news to share! CREES has won a prestigious grant Outreach Coordinator (nearly $100,000) for 2020 Lisa Giullian from the U.S. Russia Foun- dation, which will fund Office Manager many beneficial initiatives, Amanda Hill strengthen Russian Stud- ies at KU, and enhance and Applications Committee broaden our K-12 outreach and programming. (University of Northern Col- Peter Bobkowski Journalism and Mass Communications As part of the grant, CREES orado) based on his recent will offer four paid FMSO/ book, Map Men: Transnation- Mehrangiz Najafizadeh CREES Security Analyst in- al Lives and Deaths of Geog- Sociology ternships to students. We’ll raphers in the Making of East work collaboratively with oth- Central Europe. As part of the Executive Committee er Area Studies Centers to of- Palij lecture series, the New 2019-2020 fer an interdisciplinary series York-based award-winning of events connected by the Ukrainian writer Vasyl Makh- Chair theme of legacies of the Cold no presented his works of po- Vitaly Chernetsky War, including a scholarly etry and prose. -

Paris Match – S´Wiat: East/West Image Transfer in the Weekly Magazine S´Wiat (1951–1969) and the Impact of the Magnum Style on Photo-Reportage in Poland

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 Life – Paris Match – S´wiat: East/West Image Transfer in the Weekly Magazine S´wiat (1951–1969) and the Impact of the Magnum Style on Photo-Reportage in Poland Margarete Wach HCM 5 (1): 101–129 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.525 Abstract Polish photo-reportage of the 1950s and 1960s was crucially shaped by the illustrated weekly newspaper S´wiat (The World, 1951–1969). The magazine was conceived in the heyday of Stalinism and the social- ist realist doctrine to keep pace with its Western counterparts Life, Paris Match or Picture Post during the Cold War. In the new political system, the social role of photography was to agitate, but the photo- editor-in-chief, Władysław Sławny (1907–1991), designed S´wiat in the style of Henry Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’ aesthetics. He published the works of Magnum photographers and other Western colleagues. This article analyzes the massive transfer of knowledge, human resources and photography between Poland and France which flowered in the 1950s. The transcultural exchange was implemented with the aid of personal contacts and editorial practice that promoted photo transfer from the West and corresponded with the atmosphere of the ‘thaw’ after Stalin’s death. It shows that photographers trav- elled eastwards as well as westwards, and that the Iron Curtain was visually more permeable in both directions than has previously been suggested. -

Frederick Forsyth – the Devil's Alternative 4

Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative BANTAM BOOKS NEW YORK • TORONTO • LONDON • SYDNEY • AUCKLAND 4 Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative This edition contains the complete text of the original hardcover edition. NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED. THE DEVIL’S ALTERNATIVE A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with Viking Penguin. PUBLISHING HISTORY Viking edition published December 1979 Literary Guild edition March 1980 Serialized in PENTHOUSE; condensed by Reader’s Digest Condensed Books Bantam edition / July 1980 Bantam reissue / August 1995 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1979 by AHIARA International Corporation, S.A. Cover art copyright © 1995 by Bantam Books. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address: Viking Penguin, 375 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10014. If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” ISBN 0-553-26490-7 Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Bantam Double-day Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, 1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA RAD 24 23 5 Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative FOR FREDERICK STUART, WHO DOES NOT KNOW YET 6 Frederick Forsyth – The Devil’s Alternative Contents PROLOGUE.................................................................................................................................................. -

Brian Urquhart, “Finding the Hidden UN,” New York Review of Books , 27 May 2010

Brian Urquhart, “Finding the Hidden UN,” New York Review of Books , 27 May 2010 No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations by Mark Mazower Princeton University Press, 236 pp., $24.95 UN Ideas That Changed the World by Richard Jolly, Louis Emmerij, and Thomas G. Weiss, with a foreword by Kofi A. Annan Indiana University Press, 310 pp., $65.00; $24.95 (paper) (and fourteen supporting volumes in the United Nations Intellectual History Project Series) Lisa Larsen/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Image UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and General Assembly President Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit at a meeting of the assembly, September 1953 1. In its first sixty-five years the United Nations has been called many things—”a permanent partnership…among the peoples of the world for their common peace and common well-being” (President Harry Truman) and a “cesspool” (a mayor of New York). In the memoirs of a recent US ambassador to the UN, we find the heading “There Is No Such Thing as the United Nations.” While surviving these and countless other characterizations, the UN has somehow continued to reinvent itself, never to the total satisfaction of anyone. The current demand for reinvention is as pressing as any the organization has faced. The United Nations Charter is a mixture of great-power hardheadedness and a series of more or less idealistic notions about the future. The idea of giving the leaders of the victorious wartime alliance, which had been fighting since 1942 under the collective title “United Nations,” the task, as permanent members of the Security Council, of securing and if necessary enforcing the peace seemed in 1945 to be a logical course to follow. -

FOCUS Is Published Quarterly by the Boise State University Office of News Services

-t ..=> z- :a ..... • ~ "'.. 0"' -• "'z I.. i ..•0 .."'e Iu e -• 0 0 ..0 • ..I I :a "' BARBARA MCFARLAND, WEST ONE BANKER. CHILDREN'S VILLAGE VOLUNTEER. t. ~ IJ)hvld Aflt}'-/>U_ hhJ cf: &n ~ ~ tLi J~uJ. ~ 1itbaL ~ w'+Mn Nlfs ~ Qlmm~ . .{jrd Yhil~ L ~f-1- n· ~~ -rJf 1-VtlMti West One Bank. A friendly, neighborhood bank with the resources of an intermountain giant. We have more than 140 offices in Idaho, Utah, Oregon and Washington. $4.3 billion in assets. And 3,217 people with the good-hearted grace of Barbara McFarland. WE BRING A WEALTH OF EXPERIENCE To WORK. JJ'EST()NE" BANK Member FDIC Discover the Magical World of "NURSERY RHYMES" Through the Eyes of Artist JAMES CHRISTENSEN ' NURSERY RHYMES by james Christensen ©1990 The Greenwich Workshop, Inc. 30 Lindeman Dr. Trumbull, CT 06611 "Nursery Rhymes" Available as a three piece open edition print We cordially invite you to visit Gallery 601 and preview these and other James Christensen works of art, shown exclusively in Boise and Sun Valley at Gallery 601. Call for your full color brochure. 400 Sun Valley Road 601 Main Street P.O. Box 2318 Boise, Idaho 83702 Ketchum, Idaho 83340 (Located in Old Boise) 726-5899 336-5899 ~ GREENWICH WORKSHOPW a m II a a BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY VOL. XV, NO.4 SUMMER 1990 FEATURES RURAL REVIVAL 16 Turning towns around. DIRE NEEDS 21 The ills of rural health care. TOWN PORTRAIT 24 Shoshone weathers slow times. AIRWAVE EDUCAnON 26 BSU delivers education to all corners of Idaho. LOCAL HEROES 30 Some of BSU's best come from small towns. -

Over Berlin Means N-War Rei .Lohn Blanchfield Will Be the W^Rilo.S

- The Wtatiicr PAGE FOURTEEN ForM H t of D. B. W m Om t 1 / Not as cold tonight, know Bkoly hy morning Low^4hntght In Ma, 'X The Woman'a Society of the Majiche«t«r Liodg* of Maaona 1 TKuraday clMidjr, oeeiaolonal snow, Community Hapttat Church will will hold a special meeting to lltllr temporatnro <iiang«. High About Town conduct a food sale at the .1. W. night. Lodge will open at 7 o'clock In 80*. X ------- / Hale Store ThurAdav, starting at and pTOceeP t the Holnioa Funer- i MancheStejr— A City of Village Charm 'lUiine IiOdr>. No. TS^kniRhU of 10 a.m. ' — a I Home to conduct a Masonic A PyUiilM, will meet txrtnorrow at 8 Memorial service at 7;.V0 for; tun. In Orange' HiialV Grand CTan- The Most Holv Rosary Mothers Walter F,. Barbier. j MANCftEST^iR, CONN., WEDNESDAY MARCH 11 19.i9 (ClMslflsd AdvsrUi g on Pago tf) PRICE FIVE OBNTB ? ^ o r A l « t Circle will met at the home of Mrs. A Coventry gesident ha» been and hla make their of- Chsrles B. Smith, 4 Diane Dr,, to The problems of teacher eer\i- j named -by the Rockville Chapter of — --------------- :------- morrow’ night St "S o clock. Mrs. ficlal vlait to the lodge at this fleatton and a merit pay plan for the Ameriiian Red Crow.-to run a Sunshk^dirUi Council, similar meeting. A social thne with re-, l>ee Spinella will be the co teachers Will discussed at the ' to com^UK organized recently in freslunenU will fo llo w ^ ? inisiness hostess. -

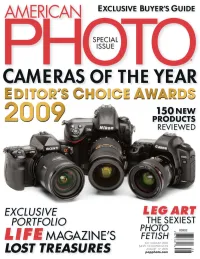

Cameras of the Year

EXCLUSIVE BUYER’S GUIDE SPECIAL ISSUE CAMERAS OF THE YEAR 150 NEW PRODUCTS REVIEWED EXCLUSIVE LEG ART PORTFOLIO THE SEXIEST PHOTO LIFE MAGAZINE’S FETISH JULY/AUGUST 2009 $4.99 ON DISPLAY UNTIL LOST TREASURES AUGUST 17, 2009 popphoto.com In this family, everyone is photogenic. The Sony® Series DSLR Cameras © 2009 Sony Electronics Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or whole is prohibited without prior written consent of Sony. Sony, the Sony logo, alpha, and the HDNA logo are trademarks of Sony. Hands-on photography workshops Presented by the experts at Popular Photography. Photo tips for any camera brand. Improve your photographic technique. Learn digital workflow. Photograph live models. "!,4)-/2% -$s#()#!'/ ),s.%79/2+ .9 Whether you’re looking to step up to the world of higher-end photography or you’re already a professional photographer, Sony has the DSLR camera for you. With features like Quick Auto Focus Live View on the 300 and professional-level 35mm full frame 24.6 Megapixel CMOS Sensor on the 900, the Sony Series DSLR cameras have every feature you need to get the best shot. Learn more at sony.com/alpha Sponsored by Sign up today! www.digitaldaysphoto.com For more information, call toll free 888-243-6464 34,/5)3 -/s0/24,!.$ /2s/2,!.$/ &, Volume XX Numberco 4 July/August 2009ntents 57 27 portfolio 57 LIFE’s Lost Treasures When a new website, never been published. LIFE.com, launched this Here’s an exclusive spring, the world began look at what we found. to get a glimpse of the vast, grand archive 78 The of the late, great LIFE Photographers magazine.