Taking a Stand? Debating the Bauhaus and Modernism, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net 2021, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polygon Radial Prints 2 Sessions – 90 Minutes Each

Polygon Radial Prints 2 Sessions – 90 minutes each Essential Question: How can we arrange polygons to show rhythm and movement? Lesson Goal Students create a bilaterally symmetrical design with various types of quadrilaterals (or triangles) and repeatedly print their design to create radial symmetry. Lesson Objectives Students will be able to: • recognize radial movement as a visual concept and apply it to their compositions. • create artworks using a printmaking technique. • describe and classify different types of quadrilaterals (or triangles) in their own and others’ art. Common Core State Standards for Mathematics Reason with shapes and their attributes. Understand that shapes in different categories (e.g., rhombuses, rectangles, and others) may share attributes (e.g., having four sides), and that the shared attributes can define a larger category (e.g., quadrilaterals). Recognize rhombuses, rectangles, and squares as examples of quadrilaterals, and draw examples of quadrilaterals that do not belong to any of these subcategories. California Visual Art Content Standards ARTISTIC PERCEPTION 1.1: Perceive and describe rhythm and movement in works of art and in the environment. CREATI VE EXPRESSION 2.6: Create an original work of art emphasizing rhythm and movement, using a selected printing process. HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL CONTEXT 3.1: Compare and describe various works of art that have a similar theme and were created at a different time. AESTHETIC VALUING 4.1: Compare and contrast selected works of art and describe them, using appropriate -

Jacob Hertzell Styles Sven Markelius's Pythagoras for Bemz

Press release LONDON, October 2015 Jacob Hertzell styles Sven Markelius’s Pythagoras for Bemz in collaboration with Ljungbergs Factory Jacob Hertzell’s curation of Pythagoras – Red by Sven Markelius for Ljungbergs Factory Watch Jacob Hertzell’s curation video here. More high-resolution images here. October 13, 2015 - Bemz, known for its designer covers for IKEA furniture, is very proud to introduce the most quintessential example of 1950s Swedish design, Pythagoras created by Sven Markelius, into its 10th Anniversary Limited Edition Designer-Curated collection. For the launch, Bemz commissioned renowned Swedish stylist, Jacob Hertzell to curate a Pythagoras covered Stockholm sofa with textiles from the existing Bemz collection. Jacob Hertzell created an inspiring milieu that exudes mid-century modern elements with clear references to the ECO-SOC session hall of the UN building in New York for which the fabric was originally created. Sven Markelius (1889-1972) was one of Sweden’s most iconic 20th century designers and a strong advocate of Swedish Functionalism. Several of his well-known textile patterns, such as Pythagoras and Prisma, have been exhibited internationally as representatives of 1950s Swedish textile design. Press release Sven Markelius / Ljungbergs Factory & Bemz – October 13, 2015 !1 The hand-printed pattern Pythagoras was originally created in 1952 when Sven Markelius participated in the architectural group designing the UN-buildings in New York. The team included other prominent architects such as Le Corbusier and Oscar Niemeyer. Tasked with designing the session hall for economic and social issues in 1952, Sven Markelius came up with the hand- printed pattern, Pythagoras for a curtain made of elegant velvet. -

Paimio Sanatorium

MARIANNA HE IKINHEIMO ALVAR AALTO’S PAIMIO SANATORIUM PAIMIO AALTO’S ALVAR ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: : PAIMIO SANATORIUM ARCHITECTURE AND TECHNOLOGY: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium TIIVISTELMÄ rkkitehti, kuvataiteen maisteri Marianna Heikinheimon arkkitehtuurin histo- rian alaan kuuluva väitöskirja Architecture and Technology: Alvar Aalto’s Paimio A Sanatorium tarkastelee arkkitehtuurin ja teknologian suhdetta suomalaisen mestariarkkitehdin Alvar Aallon suunnittelemassa Paimion parantolassa (1928–1933). Teosta pidetään Aallon uran käännekohtana ja yhtenä maailmansotien välisen moder- nismin kansainvälisesti keskeisimpänä teoksena. Eurooppalainen arkkitehtuuri koki tuolloin valtavan ideologisen muutoksen pyrkiessään vastaamaan yhä nopeammin teollis- tuvan ja kaupungistuvan yhteiskunnan haasteisiin. Aalto tuli kosketuksiin avantgardisti- arkkitehtien kanssa Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne -järjestön piirissä vuodesta 1929 alkaen. Hän pyrki Paimion parantolassa, siihenastisen uransa haastavim- massa työssä, soveltamaan uutta näkemystään arkkitehtuurista. Työn teoreettisena näkökulmana on ranskalaisen sosiologin Bruno Latourin (1947–) aktiivisesti kehittämä toimijaverkkoteoria, joka korostaa paitsi sosiaalisten, myös materi- aalisten tekijöiden osuutta teknologisten järjestelmien muotoutumisessa. Teorian mukaan sosiaalisten ja materiaalisten toimijoiden välinen suhde ei ole yksisuuntainen, mikä huo- mio avaa kiinnostavia näkökulmia arkkitehtuuritutkimuksen kannalta. Olen ymmärtänyt arkkitehtuurin -

Sven Markelius and Uno Åhrén

A Tribute to the Memory of Sven Markelius and Uno Åhrén by Eva Rudberg, PhD. Dr. Tech. architect, associate professor and former researcher at Arkitekturmuseet (museum of architecture) Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) 1 2 A Tribute to the Memory of Sven Markelius and Uno Åhrén Presented at the 2017 Annual Meeting of the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences by Eva Rudberg, PhD. Dr. Tech. architect, associate professor and former researcher at Arkitekturmuseet (museum of architecture) 3 The Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA) is an independent, learned society that promotes the engineering and economic sciences and the development of industry for the benefit of Swedish society. In cooperation with the business and academic communities, the Academy initiates and proposes measures designed to strengthen Sweden’s industrial skills base and competitiveness. For further information, please visit IVA’s website at www.iva.se. Published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences (IVA), Eva Rudberg, Phd. Dr., architect, associate professor and former researcher at Arkitekturmuseet (museum of architecture) IVA, P.O. Box 5073, SE-102 42 Stockholm, Sweden Phone: +46 8 791 29 00 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iva.se IVA-M 490 • ISSN 1102-8254 • ISBN 978-91-7082-964-2 Editor: Anna Lindberg, IVA Translation: Diane Hogsta Layout and production: Hans Melcherson, Grafisk Form, Stockholm, Sweden Photos: ArkDes, Lennart Nilsson, Lennart Olsson, Bo Törngren, Karl Schultz, Barbro Soller Printed by Pipline, Stockholm, Sweden, 2017 4 Foreword Each year the Royal at Kungsträdgården park in Stockholm. Swedish Academy of He planned suburbs such as Björkhagen, Engineering Sciences Högdalen and Vällingby while serving as (IVA) produces a book urban planning director in Stockholm. -

Architectural Research in Sweden After Le Corbusier's Projects

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/LC2015.2015.893 Experimenting with prototypes: architectural research in Sweden after Le Corbusier’s projects I. Campo-Ruiz Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Abstract: Le Corbusier’s architectural production throughout the twentieth century served as a reference for subsequent developments in architecture and urban planning in Sweden. Some of the buildings and urban plans subsequently developed in Sweden and influenced by Le Corbusier’s ideas and projects also impacted on the international architectural scene. This research analyses how the study of Le Corbusier’s works affected projects in Sweden from the 1920s to the 1970s and how they also became an international standard. Le Corbusier’s works provided a kind of prototype, with which Swedish architects experimented in alternative ways. During the 1920s, Le Corbusier’s Pavilion de l’Esprit Nouveau and the Stuttgart Weissenhofsiedlung impressed influential Swedish architect, including Uno Åhrén, Gunnar Asplund and Sven Markelius, who later became proponents of modernism in Sweden. The 1930 Stockholm Exhibition marked a breakthrough for functionalism in Sweden. After 1930, urban plans for Stockholm and its suburbs reflected some of Le Corbusier’s ideas, such as the urban plan by Sven Markelius, and Vällingby’s town centre by Leif Reinius and Sven Backström. After 1950, Léonie Geisendorf , Ralph Erskine, Sigurd Lewerentz and Peter Celsing placed considerable emphasis on rough texture in poured concrete. Lewerentz, who admired the works of Le Corbusier, designed the churches of Markuskyrkan in 1956 and St Peter’s in Klippan in 1966, with a wider international impact. -

Newtownpub-180212Vallingby.Pdf

New Towns on the Cold War Frontier Content Dodoma, Tanzania 468 *Prologue 12 Zanzibar New Town 550 A Thousand and One Garden Cities 1899-1945 The Origin and Pedigree of the New Towns Model Ciudad Guyana, Venezuela 586 Changpin, China 592 *Chapter 1 24 “An Iron Curtain has descended across the continent” Islamabad, Pakistan 598 The First Generation New Towns in the West and the Eastern Block Hanoi Vietnam 604 Stevenage, England 30 Kabul, Afghanistan 610 Hoogvliet, The Netherlands 36 Habana del Este, Cuba 616 Westelijke Tuinsteden, The Netherlands 60 Unidad Independencia, Mexico 622 Vällingby, Sweden 66 Nowe Tychy, Poland 274 *Chapter 3 716 Vernacular Spectacular Neo Beograd, Serbia 280 Critique from the Inside-Out on the Diagrams of the New Towns Eisenhuttenstadt, Germany 286 Toulouse Le Mirail, France 722 23 de Enero, Caracas 292 Poulad Shahr, Iran 728 Rourkela, India 734 *Chapter 2 298 Export to Developing Countries 10th of Ramadan, Egypt 740 Urban Planning as a Weapon in the Cold War Milton Keynes, United Kingdom 746 Arad, Israël 304 Baghdad, Iraq 310 *Epilogue 752 How to survive the twentieth century? Tema, Ghana 316 The fate of the old New Town, the rise of the new generation, and the ongoing search for context. Against a sky with cumulus clouds, the Swedish New Town Vällingby’s logo is watching over you as a giant blue eye visible from every angle. Bent in neon the turning Vällingby, Sweden V-sign is striving aft er a utopia, however, reminding you that you are close to Sweden’s capital Stockholm. Although the community centre Vällingby Centrum has acquired the Anglicism of Vällingby City, the similarity with the famous images that toured architectural journals worldwide fi ve decades ago is striking: the same characteristic TOO GOOD TO BE lampposts, the same typography snaking on signs, the same fountain with pigeons and locals, resting on benches. -

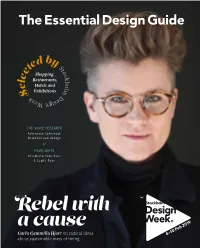

Rebel with a Cause

The Essential Essential Design Guide Design Guide by d by S t te o c Shopping, c k e Restaurants, h l o Hotels and l e m S Exhibitions D e k s e i e g n W THE SPACE DESIGNER Astronaut lifestyle inspires new design // HIGHLIGHTS Stockholm Furniture & Light Fair by Rebel with a cause Carla Cammilla Hjort on radical ideas about sustainable ways of living In 2018, the collaboration between Note Design Studio and Tarkett resulted in The Lookout, selected as the ”Editors’ Choice Award for Best Stand” at Stockholm Furniture Fair, short-listed on Dezeen Design Awards and acclaimed internationally by design publications. This year’s installation Snowtopped, exhibited in the center of Stockholm, further showcases the possibilities of Tarkett materials by exploring the colors and shapes of snow. Snowtopped Stockholm When: Monday, February 4 and continue throughout Stockholm Design Week Where: Stockholm under Stjärnorna, Brunkebergstorg 2 2019 Annons_The Stockholm Design Week_380x240.indd 1 2018-11-15 20:41 A net of electroluminescent cables wraps the façade of the Italian Cultural Institute designed by Gio’ Ponti in Stockholm. The art instal- lation, called RELATIONAL, is a work by the Italian artists Bianco- Valente. The blue lining in the darkness of the Diplomatic neighbor- Welcome to meet the darkness, hood highlights the role and the mission of the Institute as much as it represents aesthetically the exchanges and the relationships between individuals and cultures. the cold and the warm hospitality — at the launch of the 18th edition of Stockholm Design Week! AS ONE OF the major centers of contemporary Stay informed European innovation, Stockholm attracts the very Participating companies and cutting-edge international entrepreneurs, tech start-ups events will be announced at Five Italian architects furnish the Auditorium window, each and students, but the city is also a fascinating destination one with a design object meant to be a tribute to Gio’ Ponti. -

From Acceptera to Vällingby: the Discourse on Individuality and Community in Sweden (1931-54) Lucy Creagh

5 From acceptera to Vällingby: The Discourse on Individuality and Community in Sweden (1931-54) Lucy Creagh In Sweden, the relationship of modern architec- critics and considered a ‘yardstick’ for new housing ture to the welfare state starts with their common developments in the 1950s - be seen as the horizon ascendance around 1931-32. It was in this period of the discourse on ‘the individual and the mass’, that the group responsible for the design of the not only reflecting but, it might be argued, enforcing Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 - Uno Åhrén, Gunnar the social contract that was established between Asplund, Sven Markelius, Gregor Paulsson, Eskil the citizen and the state?3 Sundahl and Wolter Gahn - penned the functional- ist manifesto acceptera, and the Social Democrats Public collectivism, private individualism achieved their first majority in the Stockholm munic- The Social Democrats inherited a desperate ipal elections, also forming their first national housing situation upon their ascension to govern- government under Per Albin Hansson. The essen- ment. Despite a surge in housing construction tial terms for the debate on modern architecture in and an increase in real wages for workers over Sweden after 1931 - and indeed the welfare state the course of the 1920s, affordable, hygienic and itself - are set out in word and image on the frontis spatially adequate housing was beyond the means to acceptera: [fig. 1] of the vast majority. A housing market dominated by private speculation resulted in some of the highest The individual and the mass … rents in Europe, with an apartment of two rooms The personal or the universal? and a kitchen consuming 38% of the yearly wage Quality or quantity? for an industrial worker in 1928. -

Form Follows Fiction a Story of Stockholm Kollektivhus (1906-2018): from Modernist Ideal to Grass-Roots Appeal

Form Follows Fiction A Story of Stockholm Kollektivhus (1906-2018): From Modernist ideal to grass-roots appeal AR3EX320 Explore Lab Graduation MSc Architecture, Technische Universiteit Delft Benjamin Summers 4624831 [email protected] October 2018 Explore Lab Ir. L.C. Tummers, Ir. P. Kuitenbrouwer, Ir. G. Koskamp, Ir. E. van Dooren Abstract – This paper researches the formation of the Swedish variant of cohousing (kollektivhus) by examining the ideas and cultures which inspired it and asks the question: what has been the contribution of the architect within this history? Re-writing the script for life at home has been a collective task involving many agents of change and, perhaps most interestingly, the role of the architect in Sweden has extended beyond usual domains of operation to be crucial to the genesis and sustenance (as well as delivery) of the cohousing movement. Through writing radical manifestos, creating resident groups and indeed living in their own projects, architects have been instrumental in developing what is now a self-sustaining movement for progressive housing of a social ambition. Significantly though, it is the transition from a top-down institutional application of the concept to a grass-roots driven movement – and the accompanying integration of end- users in the design process as experts in living - that proves to be the defining moment addressed by this research. Key words – kollektivhus, cohousing, collaborative housing, ideal home, domestic labour, shared kitchens, Sweden, Stockholm 1 0 Contents 1. Introduction 4 1.1. Fetishization of the ideal home & the disparity between fiction and reality 1.2. Ideological tensions as basis for fictional atmospheres 1.3. -

Modern Swedish Design

Creagh Kåberg Modern Swedish Design Lane Three Founding Texts Lucy Creagh (coauthor and coeditor) is an architect and PhD candidate in Architectural History and Theory at Columbia University, specializing in twentieth- century Swedish architecture and consumer culture. Her dissertation on the archi- tecture of Kooperativa Förbundet was awarded the Graham Foundation’s Carter Manny Award for 2004. Her work has been published in Domus M, Transitions, and Architecture Australia, and her essay on Asger Jorn and Swedish architectural debate in the 1940s is included in Art + Architecture: New Visions, New Strategies (Alvar Aalto Foundation, 2007). Modern Swedish Design: Three Founding Texts Modern Swedish Design: Three Founding Texts Helena Kåberg (coauthor and coeditor) is a curator at the National Museum of Edited and with introductions by Lucy Creagh, Fine Arts, Stockholm. She holds a PhD in Art History from Uppsala University, which Edited and with introductions by Lucy Creagh, Helena Kåberg, and Barbara Miller Lane Helena Kåberg, and Barbara Miller Lane published her dissertation, Rationell arkitektur: Företagskontor för massproduktion och Modern Swedish Design masskommunikation (Rational Architecture: Corporate Offices for Mass Production Essay by Kenneth Frampton and Mass Communication), in 2003. She has lectured on the history of architecture Essay by Kenneth Frampton and design at institutions including Uppsala University, Konstfack, and the Cooper- 352 pages; 14 color and 246 black-and-white illustrations Hewitt National Design Museum. -

Léonie Geisendorf KONTOR VILLOR the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design 12Th April – 31St August 2014

31st 2014 August – The Architecture of Léonie Geisendorf Léonie of Architecture The The Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design 12th April upwind UPWIND · The Architecture of Léonie Geisendorf · An exhibition at the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design 2014 ARKITEKTUR · NR 2 · 2014 · VILLOR · Tham & Videgård · Elding Oscarson · Jonas Lindvall · Mikroboende · Asplunds okända hus · Valerio Olgiati ARKITEKTUR · NR 1 · 2014 · KONTOR · Ryska Posten · Mojang · AMF Fastigheter · Framtidens arbetsplats · Nya Krematoriet Skogskyrkogården upwind In the exhibition at the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design, Testbedstudio architects has designed an exhibition which invites visitors to discover the architecture of Léonie Geisendorf. Catalogue produced for the exhibition Upwind – the Architecture of Léonie Geisendorf, 12th April–31st August 2014 at the Swedish Centre for Architecture and Design, Stockholm. The exhibition marks the hundredth birthday of architect Léonie Geisendorf and presents a selection of her characterful buildings and projects, mainly from the Stockholm region. For In this room, a number of objects, photographs, stylish sports car, built on the standard Volkswagen Léonie and designs from her offi ce. Objects in drawers, programme, guided viewings etc., visit www.arkdes.se architectural drawings, models and more tell diff erent chassis, her projects can be seen as testaments to in cases and on tables provide further insight into stories – about Geisendorf’s architectural projects her dedication to improving people’s everyday life: her visions and projects. The room is an installation and about Léonie and her life. elegant, powerful projects with an attitude, projects encouraging curiosity and dialogue – a spatiality to be Curator and project manager: Tove Dumon-Wallsten/Testbed- Here you can see her car, a Karmann Ghia in which that also refl ect Geisendorf’s strong involvement inhabited. -

Airports in Architectural Competitions 1920-40

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft Airports in Architectural Competitions 1920-40 Mats T. Beckman 457 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft 458 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft KE Y W O RDS Commercial Aviation before 1940 Airport Planning Airports before 1940 Architectural Competition Air Station Design 459 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft SOM E DAT A O N T H E A U T H O R Construction Engineer and Architect. Licentiate in Engineering at Lund University 2010. Chief Architect of the Swedish CAA 1990-96. Design leader of CAA-building projects 1997-2005 Secretary General of the National Association of Swedish Architects, SAR, 1977-90. Researcher 1970-77 at the National Board of Public Building and the School of Architecture, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH ). Earlier career included work as engineering draftsman and architect. Now independant Architecture and Planning Professional living in Stockholm, Sweden. ACR O N YMS a n d E XPLANATI O N o f T E R M S CAA Civil Aviation Administration DDL, DNL, ABA, SAS First national Danish, Norwegian and Swedish Airlines. Established 1918, 1919, and 1924. DDL, DNL and ABA founded Scandinavian Airlines System, SAS, in 1948. KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, established 1919 RIBA Royal Institute of British Architects WWI, WWII Acronyms for the first World War 1914-1918 and the Second World War 1939-1945 FHS Acronym for Flyghamnsstyrelsen, Municipal Board for Airports, Stockholm 1928-46, responsible for the planning and construction of Bromma Airport. Aircraft Synonyms are airplane or aeroplane. Aircraft most common today.