February 1949 Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation Between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong,” February 04, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, APRF: F. 39, Op. 1, D. 39, Ll. 54-62. Reprinted in Andrei Ledovskii, Raisa Mirovitskaia and Vladimir Miasnikov, Sovetsko-Kitaiskie Otnosheniia, Vol. 5, Book 2, 1946-February 1950 (Moscow: Pamiatniki Istoricheskoi Mysli, 2005), pp. 66-72. Translated by Sergey Radchenko. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113318 Summary: Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong discuss the independence of Mongolia, the independence movement in Xinjiang, the construction of a railroad in Xinjiang, CCP contacts with the VKP(b), the candidate for Chinese ambassador to the USSR, aid from the USSR to China, CCP negotiations with the Guomindang, the preparatory commisssion for convening the PCM, the character of future rule in China, Chinese treaties with foreign powers, and the Sino-Soviet treaty. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation On 4 February 1949 another meeting with Mao Zedong took place in the presence of CCP CC Politburo members Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Ren Bishi, Zhu De and the interpreter Shi Zhe. From our side Kovalev I[van]. V. and Kovalev E.F. were present. THE NATIONAL QUESTION I conveyed to Mao Zedong that our CC does not advise the Chinese Com[munist] Party to go overboard in the national question by means of providing independence to national minorities and thereby reducing the territory of the Chinese state in connection with the communists' take-over of power. -

February 03, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation Between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified February 03, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong,” February 03, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, APRF: F. 39, Op. 1, D. 39, Ll. 47-53. Reprinted in Andrei Ledovskii, Raisa Mirovitskaia and Vladimir Miasnikov, Sovetsko-Kitaiskie Otnosheniia, Vol. 5, Book 2, 1946-February 1950 (Moscow: Pamiatniki Istoricheskoi Mysli, 2005), p. 62-66. Translated by Sergey Radchenko. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113239 Summary: Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong converse about the mediation talks between the CCP and the Guomindang, Yugoslavia, coordination between the communist parties of the Asian countries, and the history of the CCP. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation On the evening of 3 February 1949 another conversation took place with Mao Zedong, in which CCP CC Politburo members Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Ren Bishi and Zhu De, as well as the interpreter Shi Zhe, took part. I[van] V. Kovalev. and [Soviet China specialist] E.F. Kovalev were present from our side. ON THE FOREIGN MEDIATION IN THE TALKS BETWEEN THE GUOMINDANG AND THE CCP After mutual greetings the conversation began with me stating that we know that England, America and France stood for taking up for themselves the functions of mediation between the Guomindang and the CCP. Later, having learned somehow that the USSR and the CCP are against foreign mediation, these powers, not wishing to shame themselves, changed their position and declined mediation. In this connection it is necessary to take up seriously the questions of conspiracy and take an interest in whether there are any babbling people around the CCP, through whom this information could reach the Americans. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Typescript records of programmes, 1935-54, broadcast by the BBC Scottish Region (later Scottish Home Service). 1. February-March, 1935. 2. May-August, 1935. 3. September-December, 1935. 4. January-April, 1936. 5. May-August, 1936. 6. September-December, 1936. 7. January-February, 1937. 8. March-April, 1937. 9. May-June, 1937. 10. July-August, 1937. 11. September-October, 1937. 12. November-December, 1937. 13. January-February, 1938. 14. March-April, 1938. 15. May-June, 1938. 16. July-August, 1938. 17. September-October, 1938. 18. November-December, 1938. 19. January, 1939. 20. February, 1939. 21. March, 1939. 22. April, 1939. 23. May, 1939. 24. June, 1939. 25. July, 1939. 26. August, 1939. 27. January, 1940. 28. February, 1940. 29. March, 1940. 30. April, 1940. 31. May, 1940. 32. June, 1940. 33. July, 1940. 34. August, 1940. 35. September, 1940. 36. October, 1940. 37. November, 1940. 38. December, 1940. 39. January, 1941. 40. February, 1941. 41. March, 1941. 42. April, 1941. 43. May, 1941. 44. June, 1941. 45. July, 1941. 46. August, 1941. 47. September, 1941. 48. October, 1941. 49. November, 1941. 50. December, 1941. 51. January, 1942. 52. February, 1942. 53. March, 1942. 54. April, 1942. 55. May, 1942. 56. June, 1942. 57. July, 1942. 58. August, 1942. 59. September, 1942. 60. October, 1942. 61. November, 1942. 62. December, 1942. 63. January, 1943. -

Special Libraries, February 1949

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1949 Special Libraries, 1940s 2-1-1949 Special Libraries, February 1949 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1949 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, February 1949" (1949). Special Libraries, 1949. 2. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1949/2 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1940s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1949 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Libraries VOLUME40 . Established 1910 . NUMBER2 CONTENTS FOR FEBRUARY 1949 Religious Libraries in Profile . HOLLISWEBSTER HERING The Administration of a Library of Religion . JOHN F. LYONS Classification and Cataloging in Theological Libraries . HELENBORDNER UHRICH The Religious Library and the Professor's Attitude . R. PIERCEBEAVER Cooperation in Boston . FRANCISW. ALLEN It Will Happen in Los Angeles . HAZELA. PULLING Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux Twenty-third Annual Conference, September 17-19, 1948 . RUTH M. JACOBS International Federation of Library Associations Convenes for 14th Session in London . RUTH M. JACOBS SLA Chapter Highlights . SLA Group Highlights . Announcements . Indexed in Industrial Arts Index, Public &airs Information Service, and Library Literature ALMACLARVOE MITCHILL KATHLEENBROWN STEBBINS Editor Advertising Manager The articles which appear in SPECIALLIBRARIES express the views of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the opinion or the policy of the editorial staff and publisher. -

Participation in the Security Council by Country 1946-2010

Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council http://www.un.org/en/sc/repertoire/ Participation in the Security Council by Country 1946-2010 Country Term # of terms Total Presidencies # of Presidencies years on the Council Algeria 3 6 4 2004-2005 December 2004 1 1988-1989 May 1988,August 1989 2 1968-1969 July 1968 1 Angola 1 2 1 2003-2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 8 16 13 2005-2006 January 2005,March 2006 2 1999-2000 February 2000 1 1994-1995 January 1995 1 1987-1988 March 1987,June 1988 2 1971-1972 March 1971,July 1972 2 1966-1967 January 1967 1 1959-1960 May 1959,April 1960 2 1948-1949 November 1948,November 1949 2 Australia 4 8 8 1985-1986 November 1985 1 1973-1974 October 1973,December 1974 2 1956-1957 June 1956,June 1957 2 1946-1947 February 1946,January 1947,December 3 1947 Austria 3 6 3 2009-2010 ---no presidencies this term (yet)--- 0 1991-1992 March 1991,May 1992 2 1973-1974 November 1973 1 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998-1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000-2001 March 2000,June 2001 2 1 Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council http://www.un.org/en/sc/repertoire/ 1979-1980 October 1979 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007-2008 June 2007,August 2008 2 1991-1992 April 1991,June 1992 2 1971-1972 April 1971,August 1972 2 1955-1956 July 1955,July 1956 2 1947-1948 February 1947,January 1948,December 3 1948 Benin 2 4 3 2004-2005 February 2005 1 1976-1977 March 1976,May 1977 2 Bolivia 2 4 5 1978-1979 June 1978,November 1979 2 1964-1965 January 1964,December 1964,November 3 1965 Bosnia and Herzegovina 1 2 0 2010-2011 ---no presidencies this -

Scanned Using Fujitsu 6670 Scanner and Scandall Pro Ver 1.7

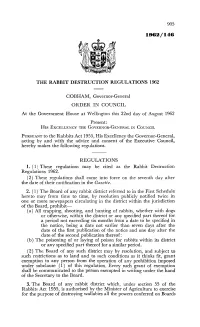

905 1962/146 THE RABBIT DESTRUCTION REGULATIONS 1962 COBHAM, Governor-General ORDER IN COUNCIL At the Government House at Wellington this 22nd day of August 1962 Present: HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL IN COUNCIL PURSUANT to the Rabbits Act 1955, His Excellency the Governor-General, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. REGULATIONS 1. (1) These regulations may be cited as the Rabbit Destruction Regulations 1962. (2) These regulations shall come into force on the seventh day after the date of their notification in the Gazette. 2. (1) The Board of any rabbit district referred to in the First Schedule hereto may from time to time, by resolution publicly notified twice in one or more newspapers circulating in the district within the jurisdiction of the Board, prohibit- (a) All trapping, shooting, and hunting of rabbits, whether with dogs or otherwise, within the district or any specified part thereof for a period not exceeding six months from a date to be specified in the notice, being a date not earlier than seven days after the date of the first publication of the notice and one day after the date of the second publication thereof: (b) The poisoning of or laying of poison for rabbits within its district or any specified part thereof for a similar period. (2) The Board of any such district may by resolution, and subject to such restrictions as to land and to such conditions as it thinks fit, grant exemption to any person from the operation of any prohibition imposed under subclause (1) of this regulation. -

Arthur Elder Papers

ARTHUR ELDER - DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS COLLECTION 20 Manuscript boxes Processed August 1965 BY PB Accession Number 75 This collection was deposited with the Labor History Archives in 1964 by Mrs. Arthur Elder, Francis Comfort, Florence Sweeny and Blanche Rinehart. Arthur Elder was a Detroiter active in the labor movement and particularly concerned with the AFL affiliate, the American Federation of Teachers. He served as vice-president of the AFT and president and secretary of the Michigan and Detroit federations. Elder was also director of the University of Michigan Workers Education Service. His dismissal from this post, in 1948, produced a controversy over the influence of General Motors in Michigan and University politics. The collection covers the period from 1921 to 1953, with emphasis on the 1940's. Among the correspondents are: Albert Einstien Mark Starr Frank Martel Norman Thomas Frank Murphy Arthur Vandenberg Important subjects covered are: History of the American Federation of Teachers The AFT and the Communist issue New York City teacher's dispute Federal aid to education Flint, Michigan dismissal cases Tenure for teachers The Workers' Education Service Description of Series: Boxes Description 1 Correspondence, reports and scrapbook relating to the AFL and education. Arranged chronologically for the period, 1941-1949. 2-10 Correspondence, reports, resolutions and hearings pertaining to the AFT. Arranged by subject for the period 1934-1950. 10-12 Correspondence, studies, resolutions, clippings and hearings relating to the MFT. Arranged by subject for the years 1937-1949. 12 Correspondence, clippings and bulletins concerning the DFT. Also minutes for the Detroit Federation of Labor, arranged by subject 1921-1951 13 Correspondence dealing with the dismissal of teachers in the Flint area for their support of the GM sit-downers, 1937-1949. -

Treaty of Peace with Italy, Signed at Paris, on 10 February 1947 Parties: Italy, France, Allied Powers Basin: Lake of Mont Cenis Date: 2/10/1947

Treaty: Treaty of Peace with Italy, signed at Paris, on 10 February 1947 Parties: Italy, France, Allied Powers Basin: Lake of Mont Cenis Date: 2/10/1947 No. 747. TREATY 1 OF PEACE WITH ITALY. SIGNED AT PARIS ON 10 FEBRUARY 1947 The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the United States of America, China, France, Australia, Belgium, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, Brazil, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Ethiopia, Greece, India, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Union of South Africa, and the People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, hereinafter referred to as "the Allied and Associated Powers", of the one part, and Italy, of the other part: Whereas Italy under the Fascist regime became a party to the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Japan, undertook a war of aggression and thereby provoked a state of war with all the Allied and Associated Powers and with other United Nations, and bears her share of responsibility for the war; and Whereas in consequence of the victories of the Allied forces, and with the assistance of the democratic elements of the Italian people, the Fascist regime in Italy was overthrown on July 25, 1943, and Italy, having surrendered unconditionally, signed terms of Armistice on September 3 and 29 the same year; and Whereas after the said Armistice Italian armed forces, both of the Government and of the Resistance Movement, took an active part in the war against Germany, and Italy declared war on Germany as from -

Internal Affairs and Foreign Affairs 1945-1949

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files INTERNAL AFFAIRS AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS 1945-1949 UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files THE FAR EAST 1945-1949 INTERNAL AFFAIRS Decimal Number 890 and FOREIGN AFFAIRS Decimal Numbers 790 and 711.90 Project Coordinator Gregory Murphy Guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. The Far East, 1945-1949 [microform]: internal affairs, decimal number 890 : foreign affairs, decimal numbers 790 and 711.90 / [project coordinator, Gregory Murphy]. microfilm reels Accompanied by printed reel guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. ISBN 1-55655-314-5 1. East Asia-Politics and government-Sources. 2. East Asia- Foreign relations-Sources. 3. United States. Dept. of State- Archives. I. Murphy, Gregory, 1960- . II. Hydrick, Blair. III. United States. Dept. of State. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) [DS503] 327.7305~dc20 92-17988 CIP The documents reproduced in this publication are among the records of the U.S. Department of State in the custody of the National Archives of the United States. No copyright is claimed in these official U.S. government records. Copyright © 1991 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-314-5. TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Scanned Using Fujitsu 6670 Scanner and Scandall Pro Ver 1.7 Software

698 1958/128 THE RABBIT DESTRUCTION REGULATIONS 1958 COBHAM, Govemor-General ORDER IN COUNCIL At the Government House at Wellington this 17th day of September 1958 Present: HIS EXCELLE NCY TilE GOVERNOR-GENERAL IN COUNCIL PURSUANT t; the Rabbits Act 1955, His Excellency the Governor-General, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. REGULATIONS 1. (I) These regulations may be cited as the Rabbit Destruction Regulations 1958. (2) These regulations shall come into force on the seventh day after the date of their notification in the Ga.::.ette. 2. In these regulations, unless the context otherwise requires, "Board" means the Board of any rabbit district to which these regulations for the time being apply. 3. These regulations shall apply to the rabbit districts constituted under the Rabbits Act 1955 referred to in the First Schedule hereto. 4. (1) The Board may from time to time, by resolution publicly notified twice in some one or more newspapers circulating in the district within the jurisdiction of the Board, prohibit- (a) All trapping, shooting, and hunting of rabbits, whether with dogs or otherwise, within the district for a period not ex ceeding six months from a date to be specified in the notice, being a date not earlier than seven days after the first publica tion of the notice and one day after the second publication thereof: (b) The poisoning of or laying of poison for rabbits within its district for a similar period. (2) The Board may by resolution, and subject to such restrictions as to land and to such conditions as it thinks fit, grant exemption to any person from the operation of any prohibition imposed under subclause (I) of this regulation. -

Publications from Niagara Area Companies

Publications from Niagara area Companies The Tapping Pot, the Electro Metallurgical Company, Unit of Union Carbide and Carbon Corporation Issues: Vol. 18, No. 7---July, 1948 Cooperation, Kimberly-Clark Corporation Issues: March-April 1940 May-June 1942 March-April 1944 May-June 1944 The Lowdown, Lake Ontario Ordnance Works Issues: Volume 1, No. 3-- November, 1942 The Carbo-Wheel, The Employees’ News-Magazine of the Carborundum Company, Niagara Falls, N.Y. Vol. 2, No. 9—September, 1944 (only cover) Vol. 2, No. 12—December, 1944 Vol.3, No. 1—January, 1945 Vol. 3, No.2—February, 1945 (2 copies) Vol. 3, No. 3—March, 1945 Vol. 3, No. 11—December, 1945 Vol. 4, No. 2—February, 1946 Vol. 4, No. 3—March, 1946 Vol. 4, No. 4—April, 1946 Vol. 4, No.7—August, 1946 Vol. 4, No. 8—September, 1946 Vol. 4, No. 9—October, 1946 Vol. 4, No. 10—November, 1946 Vol. 4, No. 11—December, 1946 Vol. 5, No. 1---January, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 2—February, 1947 Vol. 5, No.3—March, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 4—April, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 5—May, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 6—June, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 8—August, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 9—September, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 10—October, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 11—November, 1947 Vol. 5, No. 12—December, 1947 Vol. 6, No. 1—January, 1948 Vol. 6, No. 2—February, 1948 Vol. 6, No. 3—March, 1948 Vol. 6, No. 4—April, 1948 Vol. 6, No. 7—July, 1948 Vol. 6, No. 8—August, 1948 Vol.