Which Side Are You On? the Worlds of Grant Morrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

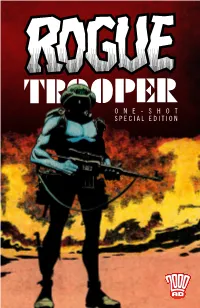

One-Shot Special Edition Script Gerry Finley-Day Guy Adams Art Dave Gibbons Darren Douglas Lee Carter Letters Simon Bowland Dave Gibbons

ONE-SHOT SPECIAL EDITION SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY GUY ADAMS ART DAVE GIBBONS DARREN DOUGLAS LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND DAVE GIBBONS REBELLION Creative Director and CEO Junior Graphic Novels Editor JASON KINGSLEY OLIVER BALL Chief Technical Officer Graphic Design CHRIS KINGSLEY SAM GRETTON, OZ OSBORNE & MAZ SMITH Head of Books & Comics Reprographics BEN SMITH JOSEPH MORGAN 2000 AD Editor in Chief PR & Marketing MATT SMITH MICHAEL MOLCHER Graphic Novels Editor Publishing Assistant KEITH RICHARDSON OWEN JOHNSON Rogue Trooper Published by Rebellion, Riverside House, Osney Mead, Oxford OX2 0ES. All contents © 1981, 2014, 2015, 2018 Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. All rights reserved. Rogue Trooper is a trademark of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. Reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form or by any means in whole or part without prior permission of Rebellion 2000 AD Ltd. is strictly forbidden. No similarity between any of the fictional names, characters, persons and/or institutions herein with those of any living or dead persons or institutions is intended (except for satirical purposes) and any such similarity is purely coincidental. ROGUE TROOPER SCRIPT GERRY FINLEY-DAY ART DAVE GIBBONS LETTERS DAVE GIBBONS ROGUE TROOPER DREGS OF WAR SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE FEAST SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART LEE CARTER LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND ROGUE TROOPER THE DEATH OF A DEMON SCRIPT GUY ADAMS ART DARREN DOUGLAS LETTERS SIMON BOWLAND THE END ROGUE TROOPER GRAPHIC NOVELS FROM 2000 AD ROGUE TROOPER ROGUE -

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

Club Add 2 Page Designoct07.Pub

H M. ADVS. HULK V. 1 collects #1-4, $7 H M. ADVS FF V. 7 SILVER SURFER collects #25-28, $7 H IRR. ANT-MAN V. 2 DIGEST collects #7-12,, $10 H POWERS DEF. HC V. 2 H ULT FF V. 9 SILVER SURFER collects #12-24, $30 collects #42-46, $14 H C RIMINAL V. 2 LAWLESS H ULTIMATE VISON TP collects #6-10, $15 collects #0-5, $15 H SPIDEY FAMILY UNTOLD TALES H UNCLE X-MEN EXTREMISTS collects Spidey Family $5 collects #487-491, $14 Cut (Original Graphic Novel) H AVENGERS BIZARRE ADVS H X-MEN MARAUDERS TP The latest addition to the Dark Horse horror line is this chilling OGN from writer and collects Marvel Advs. Avengers, $5 collects #200-204, $15 Mike Richardson (The Secret). 20-something Meagan Walters regains consciousness H H NEW X-MEN v5 and finds herself locked in an empty room of an old house. She's bleeding from the IRON MAN HULK back of her head, and has no memory of where the wound came from-she'd been at a collects Marvel Advs.. Hulk & Tony , $5 collects #37-43, $18 club with some friends . left angrily . was she abducted? H SPIDEY BLACK COSTUME H NEW EXCALIBUR V. 3 ETERNITY collects Back in Black $5 collects #16-24, $25 (on-going) H The End League H X-MEN 1ST CLASS TOMORROW NOVA V. 1 ANNIHILATION A thematic merging of The Lord of the Rings and Watchmen, The End League follows collects #1-8, $5 collects #1-7, $18 a cast of the last remaining supermen and women as they embark on a desperate and H SPIDEY POWER PACK H HEROES FOR HIRE V. -

Aug CUSTOMER ORDER FORM

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18 aug 2013 aug COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Aug13 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 3:05:51 PM Available only DEADPOOL: “TACO ENTHUSIAST” from your local BLUE T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! THE WALKING DEAD: STREET FIGHTER: DOCTOR WHO: “THE DIXON BROS.” “THE STREETS” “DON’T BLINK” GLOW ZIP HOODIE RED T-SHIRT IN THE DARK T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now 8 Aug 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 7/3/2013 10:34:19 AM PrETTY DEADLY #1 ImAgE COmICS THE SHAOLIN COWBOY #1 DArk HOrSE COmICS THE SANDmAN: OVErTUrE #1 DC COmICS / VErTIgO VELVET #1 ELFQUEST SPECIAL: ImAgE COmICS THE FINAL QUEST DArk HOrSE COmICS SAmUrAI JACk #1 IDW PUBLISHINg SUPErmAN/WONDEr mArVEL kNIgHTS: WOmAN #1 SPIDEr-mAN #1 DC COmICS mArVEL COmICS Aug13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 7/3/2013 9:04:01 AM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Uber Volume 1 Enhanced HC l AVATAR PRESS Imagine Agents #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Shadow Now #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Cryptozoic Man #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Peanuts Every Sunday 1952-1955 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Battling Boy GN/HC l :01 FIRST SECOND Letter 44 #1 l ONI PRESS 1 1 Ben 10 Omniverse Volume 1: Ghost Ship GN l PERFECT SQUARE X-O Manowar Deluxe HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Miss Peregrine’s Home For Peculiar Children HC l YEN PRESS BOOKS The Superman Files HC l COMICS Doctor Who 50th Anniversary Anthology l DOCTOR WHO Doctor Who: The Vault: Treasures from the First 50 Years HC l DOCTOR WHO Dc Comics Guide To Creating Comics Sc l HOW-TO Star Trek: Mr. -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2010 “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep’Em Down at the Farm Now That They’Ve Seen Paree?”: France

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2010 American Shakespeare / Comic Books “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics Nicolas Labarre Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/4943 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.4943 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference Nicolas Labarre, ““How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2010, Online since 02 September 2010, connection on 22 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/4943 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/transatlantica.4943 This text was automatically generated on 22 September 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France... 1 “How ‘ya gonna keep’em down at the farm now that they’ve seen Paree?”: France in Super Hero Comics Nicolas Labarre 1 Super hero comics are a North-American narrative form. Although their ascendency points towards European ancestors, and although non-American heroes have been sharing their characteristics for a long time, among them Obelix, Diabolik and many manga characters, the cape and costume genre remains firmly grounded in the United States. It is thus unsurprising that, with a brief exception during the Second World War, super hero narratives should have taken place mostly in the United States (although Metropolis, Superman’s headquarter, was notoriously based on Toronto) or in outer space. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

1 in Our Culture, the Decisive Political Conflict, Which Governs Every

THE GRAPHIC NOVEL SOPHIST: GRANT MORRISON’S ANIMAL MAN IAN HORNSBY In our culture, the decisive political conflict, which governs every conflict, is that between the animality and the humanity of man. (Agamben) The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, in his book The Open: Man and Animal (2004), argues that while in early modern western philosophy, at least since Descartes, the human has been consistently described as the separation of body and mind, we would do better to re-describe the human, as that which results from the practical and political division of humanity from animality. After beginning with a brief outline of Agamben’s concept of ‘Bare Life’, as the empty interval between human and animal, which is neither “human life” nor “animal life,” but a life separated and excluded from itself; I will closely examine these ideas in relation to Grant Morrison’s DC Vertigo comic Animal Man (1988-90) to disclose aspects of sophist logic displaced in Agamben’s text. 1 § 1 Bare Life The concept of ‘bare life’ (2004, 38) is central to the philosophy of Agamben, not least, because he sees this empty interval between the animal and the human as the site for rethinking the future of politics and philosophy and preventing the onward progress of the ‘anthropological machine’ (2004, 37). A term he uses to describe the mechanism that has and continues to produces our recognition of what it means to be human. As Agamben states ‘It is an optical Machine constructed of a series of mirrors in which man, looking at himself, sees his own image always already deformed in the features of an ape. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Batman Miniature Game Teams

TEAMS IN Gotham MAY 2020 v1.2 Teams represent an exciting new addition to the Batman Miniature Game, and are a way of creating themed crews that represent the more famous (and infamous) groups of heroes and villains in the DC universe. Teams are custom crews that are created using their own rules instead of those found in the Configuring Your Crew section of the Batman Miniature Game rulebook. In addition, Teams have some unique special rules, like exclusive Strategies, Equipment or characters to hire. CONFIGURING A TEAM First, you must choose which team you wish to create. On the following pages, you will find rules for several new teams: the Suicide Squad, Bat-Family, The Society, and Team Arrow. Models from a team often don’t have a particular affiliation, or don’t seem to have affiliations that work with other members, but don’t worry! The following guidelines, combined with the list of playable characters in appropriate Recruitment Tables, will make it clear which models you may include in your custom crew. Once you have chosen your team, use the following rules to configure it: • You must select a model to be the Team’s Boss. This model doesn’t need to have the Leader or Sidekick Rank – s/he can also be a Free Agent. See your team’s Recruitment Table for the full list of characters who can be recruited as your team’s Boss. • Who is the Boss in a Team? 1. If there is a model with Boss? Always present, they MUST be the Boss, regardless of a rank.