The Royal Navy and Economic Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Family of Admiral Sir Philip Broke, Bt

FRIENDS OF HMS TRINCOMALEE SUMMER 2016 The Life of Sir Philip Broke TS Foudroyant at the Movies Mess Deck Crossword / Wordsearch / Future events Annual General Meeting Notice is hereby given of our: Annual General Meeting 2016 Wednesday 14th September at 7.30pm Hart Village Hall, Hartlepool, TS27 3AW AGENDA: 1. Welcome and apologies for absence 2. Minutes of the last Annual General Meeting held on 23rd September 2015 3. Chairman’s report 4. Honorary Treasurer’s report and accounts for the 12 month period ending 31st March 2016 5. Election of Trustees 6. Appointment of Honorary Auditor 7. Any other business (Notified to the Secretary prior to the meeting) Members interested in joining the Committee are warmly encouraged to make themselves known to the Secretary of the ‘Friends’. All candidates for election need at least one nominee from the present Committee. The closing time for all nominations to be submitted to the Secretary is 2nd September 2016. Ian Purdy Hon. Secretary Any correspondence concerning the Friends Association should be sent to: The Secretary, Ian Purdy 39 The Poplars, Wolviston, Billingham TS22 5LY Tel: 01740 644381 E-mail: [email protected] Correspondence and contributions for the magazine to: The Editor, Hugh Turner Chevin House, 30 Kingfisher Close, Bishop Cuthbert, Hartlepool TS26 0GA Tel: 01429 236848 E-Mail: [email protected] Membership matters directed to: The Membership Secretary, Martin Barker The Friends of HMS Trincomalee, Jackson Dock, Maritime Avenue, Hartlepool TS24 0XZ E-Mail: [email protected] –– 22 –– Editorial At the time of writing this editorial, our negotiations with the National Museum of the Royal Navy are still in progress. -

A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Sailor of King George Author: Frederick Hoffman Release Date: December 13, 2008 [Ebook 27520] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE*** [I] A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE THE JOURNALS OF CAPTAIN FREDERICK HOFFMAN, R.N. 1793–1814 EDITED BY A. BECKFORD BEVAN AND H.B. WOLRYCHE-WHITMORE v WITH ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET 1901 [II] BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS, LONDON AND TONBRIDGE. [III] PREFACE. In a memorial presented in 1835 to the Lords of the Admiralty, the author of the journals which form this volume details his various services. He joined the Navy in October, 1793, his first ship being H.M.S. Blonde. He was present at the siege of Martinique in 1794, and returned to England the same year in H.M.S. Hannibal with despatches and the colours of Martinique. For a few months the ship was attached to the Channel Fleet, and then suddenly, in 1795, was ordered to the West Indies again. Here he remained until 1802, during which period he was twice attacked by yellow fever. The author was engaged in upwards of eighteen boat actions, in one of which, at Tiberoon Bay, St. -

Hornblower's Ships

Names of Ships from the Hornblower Books. Introduction Hornblower’s biographer, C S Forester, wrote eleven books covering the most active and dramatic episodes of the life of his subject. In addition, he also wrote a Hornblower “Companion” and the so called three “lost” short stories. There were some years and activities in Hornblower’s life that were not written about before the biographer’s death and therefore not recorded. However, the books and stories that were published describe not only what Hornblower did and thought about his life and career but also mentioned in varying levels of detail the people and the ships that he encountered. Hornblower of course served on many ships but also fought with and against them, captured them, sank them or protected them besides just being aware of them. Of all the ships mentioned, a handful of them would have been highly significant for him. The Indefatigable was the ship on which Midshipman and then Acting Lieutenant Hornblower mostly learnt and developed his skills as a seaman and as a fighting man. This learning continued with his experiences on the Renown as a lieutenant. His first commands, apart from prizes taken, were on the Hotspur and the Atropos. Later as a full captain, he took the Lydia round the Horn to the Pacific coast of South America and his first and only captaincy of a ship of the line was on the Sutherland. He first flew his own flag on the Nonsuch and sailed to the Baltic on her. In later years his ships were smaller as befitted the nature of the tasks that fell to him. -

Naval Documents of the American Revolution

Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 4 AMERICAN THEATRE: Feb. 19, 1776–Apr. 17, 1776 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Feb. 1, 1776–May 25, 1776 AMERICAN THEATRE: Apr. 18, 1776–May 8, 1776 Part 7 of 7 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1969 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2012 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. MAY 1776 1413 5 May (Sunday) JOURNAL OF H.M. SLOOPHunter, CAPTAINTHOMAS MACKENZIE May 1776 ' Remarks &c in Quebec 1776 Sunday 5 at 5 A M Arrived here his Majestys Sloop surprize at 8 the surprise & Sloop Martin with part of the 29th regt landed with their Marines Light Breezes & fair Sally'd out & drove the rebels off took at different places several pieces of Cannon some Howitzers & a Quantity of Ammunition 1. PRO, Admiralty 511466. JOURNALOF H.M.S. Surprize, CAPTAINROBERT LINZEE May 1776 Runing up the River [St. Lawrence] - Sunday 5. at 4 AM. Weigh'd and came to sail, at 9 Got the Top Chains up, and Slung the yards the Island of Coudre NEBE, & Cape Tor- ment SW1/2W. off Shore 1% Mile. At 10 Came too with the Best Bower in 11 fms. of Water, Veer'd to 1/2 a Cable. at 11 Employ'd racking the Lanyards of the Shrouds, and getting every thing ready for Action. Most part little Wind and Cloudy, Remainder Modre and hazey, at 2 [P.M.] Weigh'd and came to sail, Set Studding sails, nock'd down the Bulk Heads of the Cabbin at 8 PM Came too with the Best Bower in 13 £ms Veer'd to % of a Cable fir'd 19 Guns Signals for the Garrison of Quebec. -

Rhodri Evans

Rhodri Evans The Cosmic Microwave Background How It Changed Our Understanding of the Universe Astronomers’ Universe More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/6960 Rhodri Evans The Cosmic Microwave Background How It Changed Our Understanding of the Universe 123 Rhodri Evans School of Physics & Astronomy Cardiff University Cardiff United Kingdom ISSN 1614-659X ISSN 2197-6651 (electronic) ISBN 978-3-319-09927-9 ISBN 978-3-319-09928-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-09928-6 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: : 2014957530 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

Freedom by Reaching the Wooden World: American Slaves and the British Navy During the War of 1812

Freedom by Reaching the Wooden World: American Slaves and the British Navy during the War of 1812. Thomas Malcomson Les noirs américains qui ont échappé à l'esclavage pendant la guerre de 1812 l'ont fait en fuyant vers les navires de la marine britannique. Les historiens ont débattu de l'origine causale au sein de cette histoire, en la plaçant soit entièrement dans les mains des esclaves fugitifs ou les Britanniques. L'historiographie a mis l'accent sur l'expérience des réfugiés dans leur lieu de réinstallation définitive. Cet article réexamine la question des causes et se concentre sur la période comprise entre le premier contact des noirs américains qui ont fuit l'esclavage et la marine britannique, et le départ définitif des ex-esclaves avec les Britanniques à la fin de la guerre. L'utilisation des anciens esclaves par les Britanniques contre les Américains en tant que guides, espions, troupes armées et marins est examinée. Les variations locales en l'interaction entre les esclaves fugitifs et les Britanniques à travers le théâtre de la guerre, de la Chesapeake à la Nouvelle-Orléans, sont mises en évidence. As HMS Victorious lay at anchor in Lynnhaven Bay, off Norfolk, in the early morning hours of 10 March 1813, a boat approached from the Chesapeake shore.1 Its occupants, nine American Black men drew the attention of the sailors in the guard boat circling the 74 gun ship. The men were runaway slaves. After a cautious inspection, the guard boat’s crew towed them to the Victorious where the nine Black men climbed up the ship’s side and entered freedom. -

The Naval Engineer

THE NAVAL ENGINEER SPRING/SUMMER 2019, VOL 06, EDITION NO.2 All correspondence and contributions should be forwarded to the Editor: Welcome to the new edition of TNE! Following the successful relaunch Clare Niker last year as part of our Year of Engineering campaign, the Board has been extremely pleased to hear your feedback, which has been almost entirely Email: positive. Please keep it coming, good or bad, TNE is your journal and we [email protected] want to hear from you, especially on how to make it even better. By Mail: ‘..it’s great to see it back, and I think you’ve put together a great spread of articles’ The Editor, The Naval Engineer, Future Support and Engineering Division, ‘Particularly love the ‘Recognition’ section’ Navy Command HQ, MP4.4, Leach Building, Whale Island, ‘I must offer my congratulations on reviving this important journal with an impressive Portsmouth, Hampshire PO2 8BY mix of content and its presentation’ Contributions: ‘..what a fantastic publication that is bang up to date and packed full of really Contributions for the next edition are exciting articles’ being sought, and should be submitted Distribution of our revamped TNE has gone far and wide. It is hosted on by: the MOD Intranet, as well as the RN and UKNEST webpages. Statistics taken 31 July 2019 from the external RN web page show that there were almost 500 visits to the TNE page and people spent over a minute longer on the page than Contributions should be submitted average. This is in addition to all the units and sites that received almost electronically via the form found on 2000 hard copies, those that have requested electronic soft copies, plus The Naval Engineer intranet homepage, around 700 visitors to the internal site. -

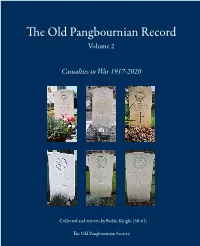

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

'The Admiralty War Staff and Its Influence on the Conduct of The

‘The Admiralty War Staff and its influence on the conduct of the naval between 1914 and 1918.’ Nicholas Duncan Black University College University of London. Ph.D. Thesis. 2005. UMI Number: U592637 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592637 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS Page Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Abbreviations 6 Introduction 9 Chapter 1. 23 The Admiralty War Staff, 1912-1918. An analysis of the personnel. Chapter 2. 55 The establishment of the War Staff, and its work before the outbreak of war in August 1914. Chapter 3. 78 The Churchill-Battenberg Regime, August-October 1914. Chapter 4. 103 The Churchill-Fisher Regime, October 1914 - May 1915. Chapter 5. 130 The Balfour-Jackson Regime, May 1915 - November 1916. Figure 5.1: Range of battle outcomes based on differing uses of the 5BS and 3BCS 156 Chapter 6: 167 The Jellicoe Era, November 1916 - December 1917. Chapter 7. 206 The Geddes-Wemyss Regime, December 1917 - November 1918 Conclusion 226 Appendices 236 Appendix A. -

BLACK LONDON Life Before Emancipation

BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation ^^^^k iff'/J9^l BHv^MMiai>'^ii,k'' 5-- d^fli BP* ^B Br mL ^^ " ^B H N^ ^1 J '' j^' • 1 • GRETCHEN HOLBROOK GERZINA BLACK LONDON Other books by the author Carrington: A Life BLACK LONDON Life before Emancipation Gretchen Gerzina dartmouth college library Hanover Dartmouth College Library https://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/digital/publishing/ © 1995 Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina All rights reserved First published in the United States in 1995 by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey First published in Great Britain in 1995 by John Murray (Publishers) Ltd. The Library of Congress cataloged the paperback edition as: Gerzina, Gretchen. Black London: life before emancipation / Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 0-8135-2259-5 (alk. paper) 1. Blacks—England—London—History—18th century. 2. Africans— England—London—History—18th century. 3. London (England)— History—18th century. I. title. DA676.9.B55G47 1995 305.896´0421´09033—dc20 95-33060 CIP To Pat Kaufman and John Stathatos Contents Illustrations ix Acknowledgements xi 1. Paupers and Princes: Repainting the Picture of Eighteenth-Century England 1 2. High Life below Stairs 29 3. What about Women? 68 4. Sharp and Mansfield: Slavery in the Courts 90 5. The Black Poor 133 6. The End of English Slavery 165 Notes 205 Bibliography 227 Index Illustrations (between pages 116 and 111) 1. 'Heyday! is this my daughter Anne'. S.H. Grimm, del. Pub lished 14 June 1771 in Drolleries, p. 6. Courtesy of the Print Collection, Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. 2. -

A British Perspective on the War of 1812 by Andrew Lambert

A British Perspective on the War of 1812 by Andrew Lambert The War of 1812 has been referred to as a victorious “Second A decade of American complaints and economic restrictions action. Finally, on January 14th 1815 the American flagship, the rights and impressment. By accepting these terms the Americans War for Independence,” and used to define Canadian identity, only served to convince the British that Jefferson and Madison big 44 gun frigate USS President commanded by Stephen Decatur, acknowledged the complete failure of the war to achieve any of but the British only remember 1812 as the year Napoleon were pro-French, and violently anti-British. Consequently, was hunted down and defeated off Sandy Hook by HMS their strategic or political aims. Once the treaty had been marched to Moscow. This is not surprising. In British eyes, when America finally declared war, she had very few friends Endymion. The American flagship became signed, on Christmas Eve 1814, the the conflict with America was an annoying sideshow. The in Britain. Many remembered the War of Independence, some HMS President, a name that still graces the list British returned the focus to Europe. Americans had stabbed them in the back while they, the had lost fathers or brothers in the fighting; others were the of Her Majesty’s Fleet. The war at sea had British, were busy fighting a total war against the French sons of Loyalists driven from their homes. turned against America, the U.S. Navy had The wisdom of their decision soon Empire, directed by their most inveterate enemy.