Edvard Munch's Fatal Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

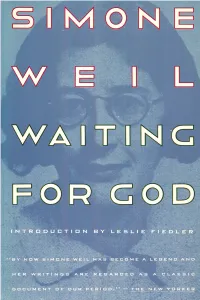

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Knut Hamsun at the Movies in Transnational Contexts

KNUT HAMSUN AT THE MOVIES IN TRANSNATIONAL CONTEXTS Arne Lunde This article is a historical overview that examines how the literary works of Knut Hamsun have been adapted into films over the past century. This “Cook’s Tour” of Hamsun at the movies will trace how different national and transnational cinemas have appropri- ated his novels at different historical moments. This is by no means a complete and exhaustive overview. The present study does not cite, for example, Hamsun films made for television or non-feature length Hamsun films. Thus I apologize in advance for any favorite Hamsun-related films that may have been overlooked. But ideally the article will address most of the high points in the international Hamsun filmography. On the subject of the cinema, Hamsun is famously quoted as having said in the 1920s: “I don’t understand film and I’m at home in bed with the flu” (Rottem 2). Yet while Hamsun was volun- tarily undergoing psychoanalysis in Oslo in 1926, he writes to his wife Marie about wishing to learn to dance and about going to the movies more (Næss 129). Biographer Robert Ferguson reports that in 1926, Hamsun began regularly visiting the cinemas in Oslo “taking great delight in the experience, particularly enjoying adventure films and comedies” (Ferguson 286). So we have the classic Hamsun paradox of conflicting statements on a subject, in this case the movies. Meanwhile, it is also important to remember that the films that Hamsun saw in 1926 would still have been silent movies with intertitles and musical accompaniment, and thus his poor hearing would not have been an impediment to his enjoyment. -

Correspondences – Jean Sibelius in a Forest of Image and Myth // Anna-Maria Von Bonsdorff --- FNG Research Issue No

Issue No. 6/20161/2017 CorrespondencesNordic Art History in – the Making: Carl Gustaf JeanEstlander Sibelius and in Tidskrift a Forest för of Bildande Image and Konst Myth och Konstindustri 1875–1876 Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff SusannaPhD, Chief Pettersson Curator, //Finnish PhD, NationalDirector, Gallery,Ateneum Ateneum Art Museum, Art Museum Finnish National Gallery First published in RenjaHanna-Leena Suominen-Kokkonen Paloposki (ed.), (ed.), Sibelius The Challenges and the World of Biographical of Art. Ateneum ResearchPublications in ArtVol. History 70. Helsinki: Today Finnish. Taidehistoriallisia National Gallery tutkimuksia / Ateneum (Studies Art inMuseum, Art History) 2014, 46. Helsinki:81–127. Taidehistorian seura (The Society for Art History in Finland), 64–73, 2013 __________ … “så länge vi på vår sida göra allt hvad i vår magt står – den mår vara hur ringa Thankssom to his helst friends – för in att the skapa arts the ett idea konstorgan, of a young värdigt Jean Sibeliusvårt lands who och was vår the tids composer- fordringar. genius Stockholmof his age developed i December rapidly. 1874. Redaktionen”The figure that. (‘… was as createdlong as wewas do emphatically everything we anguished, can reflective– however and profound. little that On maythe beother – to hand,create pictures an art bodyof Sibelius that is showworth us the a fashionable, claims of our 1 recklesscountries and modern and ofinternational our time. From bohemian, the Editorial whose staff, personality Stockholm, inspired December artists to1874.’) create cartoons and caricatures. Among his many portraitists were the young Akseli Gallen-Kallela1 and the more experienced Albert Edelfelt. They tended to emphasise Sibelius’s high forehead, assertiveThese words hair were and addressedpiercing eyes, to the as readersif calling of attention the first issue to ofhow the this brand charismatic new art journal person created compositionsTidskrift för bildande in his headkonst andoch thenkonstindustri wrote them (Journal down, of Finein their Arts entirety, and Arts andas the Crafts) score. -

A Comparative Study of the Bell Jar and the Poetry of a Few Indian Women Poets

AKHTAR JAMAL KHAN, BIBHUDUTT DASH Approaches to Angst and the Male World: A Comparative Study of The Bell Jar and the Poetry of a Few Indian Women Poets Pitting Sylvia Plath’s speakers against male chauvinism is a usual critical practice, but this antinomy primarily informs her work. Most of her writings express an anguish that transcends the torment of the individual speakers in question, and voices or represents the despair of all women who undergo similar anguish. As David Holbrook writes: “When one knows Sylvia Plath’s work through and through, and has penetrated her inner topography, the confusion, hate and madness become frighteningly apparent” (357). The besetting question is what causes this angst. Apparently, a stifling patriarchal system that sty- mies woman’s freedom seems to be the cause of this anguish. However, it would be lopsided to say that Plath’s work is simply an Armageddon between man and woman. This paper compares Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar (1963) and the poetry of a few twentieth-century Indian women poets such as Kamala Das, Mamta Kalia, Melanie Silgardo, Eunice de Souza, Smita Agarwal and Tara Patel to study the angst experienced by the speakers and their approaches to the male world. Here, the term ‘male world’ refers to any social condition where man overtly or tacitly punctuates a woman’s life. Thus, it precisely refers to a patriarchal social order. Talking about twentieth-century poetry and making references to the posi- tion of women poets, John Brannigan writes: “In their time, Elizabeth Jennings, Sylvia Plath and Eliza- beth Bishop seemed isolated and remote from the male-dominated generation of the fifties and sixties” (Poplawski 632). -

Anxiety, Angst, Anguish in Fin De Siècle Art and Literature

Anxiety, Angst, Anguish in Fin de Siècle Art and Literature Anxiety, Angst, Anguish in Fin de Siècle Art and Literature Edited by Rosina Neginsky, Marthe Segrestin and Luba Jurgenson Anxiety, Angst, Anguish in Fin de Siècle Art and Literature Edited by Rosina Neginsky, Marthe Segrestin and Luba Jurgenson This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Rosina Neginsky, Marthe Segrestin, Luba Jurgenson and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4383-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4383-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix Introduction .............................................................................................. xiv Part I: Thresholds Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Le Pays intermédiaire saloméen: un lieu entre expérience de l’angoisse et libération créatrice – The Salomean Land Between: A Place between Experience of Anguish and Creative Liberation Britta Benert Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

Géraldine Crahay a Thesis Submitted in Fulfilments of the Requirements For

‘ON AURAIT PENSÉ QUE LA NATURE S’ÉTAIT TROMPÉE EN LEUR DONNANT LEURS SEXES’: MASCULINE MALAISE, GENDER INDETERMINACY AND SEXUAL AMBIGUITY IN JULY MONARCHY NARRATIVES Géraldine Crahay A thesis submitted in fulfilments of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in French Studies Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures June 2015 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix Declaration and Consent ........................................................................................................... xi Introduction: Masculine Ambiguities during the July Monarchy (1830‒48) ............................ 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework: Masculinities Studies and the ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity ............................. 4 Literature Overview: Masculinity in the Nineteenth Century ......................................................... 9 Differences between Masculinité and Virilité ............................................................................... 13 Masculinity during the July Monarchy ......................................................................................... 16 A Model of Masculinity: -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

An Analysis of Heracles As a Tragic Hero in the Trachiniae and the Heracles

The Suffering Heracles: An Analysis of Heracles as a Tragic Hero in The Trachiniae and the Heracles by Daniel Rom Thesis presented for the Master’s Degree in Ancient Cultures in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Annemaré Kotzé March 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis is an examination of the portrayals of the Ancient Greek mythological hero Heracles in two fifth century BCE tragic plays: The Trachiniae by Sophocles, and the Heracles by Euripides. Based on existing research that was examined, this thesis echoes the claim made by several sources that there is a conceptual link between both these plays in terms of how they treat Heracles as a character on stage. Fundamentally, this claim is that these two plays portray Heracles as a suffering, tragic figure in a way that other theatre portrayals of him up until the fifth century BCE had failed to do in such a notable manner. This thesis links this claim with a another point raised in modern scholarship: specifically, that Heracles‟ character and development as a mythical hero in the Ancient Greek world had given him a distinct position as a demi-god, and this in turn affected how he was approached as a character on stage. -

EDVARD MUNCH Cast

EDVARD MUNCH EDVARD MUNCH Cast EDVARD MUNCH Geir Westby MRS. HEIBERG Gros Fraas The Munch Family in 1868 The Munch Family in 1875 SOPHIE Kjersti Allum SOPHIE Inger Berit Oland EDVARD Erik Allum EDVARD Åmund Berge LAURA Susan Troldmyr LAURA Camilla Falk PETER ANDREAS Ragnvald Caspari PETER ANDREAS Erik Kristiansen INGER Katja Pedersen INGER Anne Marie Dæhli HOUSEMAID Hjørdis Ulriksen The Munch Family in 1884 Also appearing DR. CHRISTIAN MUNCH Johan Halsbog ODA LASSON Eli Ryg LAURA CATHRINE MUNCH Gro Jarto CHRISTIAN KROHG Knut Kristiansen TANTE KAREN BJØLSTAD Lotte Teig FRITZ THAULOW Nils Eger Pettersen INGER MUNCH Rachel Pedersen SIGBJØRN OBSTFELDER Morten Eid LAURA MUNCH Berit Rytter Hasle VILHELM KRAG Håkon Gundersen PETER ANDREAS MUNCH Gunnar Skjetne DR. THAULOW Peter Esdaile HOUSEMAID Vigdis Nilssen SIGURD BØDTKER Dag Myklebust JAPPE NILSSEN Torstein Hilt MISS DREFSEN Kristin Helle-Valle AASE CARLSEN Ida Elisabeth Dypvik CHARLOTTE DØRNBERGER Ellen Waaler The Bohemians of Kristiania Patrons of the Café "Zum Schwarzen Ferkel" HANS JÆGER Kåre Stormark AUGUST STRINDBERG Alf Kåre Strindberg DAGNY JUELL Iselin von Hanno Bast STANISLAV PRZYBYSZEWSKI Ladislaw Rezni_ek Others BENGT LIDFORS Anders Ekman John Willy Kopperud Asle Raaen ADOLF PAUL Christer Fredberg Ove Bøe Axel Brun DR. SCHLEICH Kai Olshausen Arnulv Torbjørnsen Geo von Krogh DR. SCHLITTGEN Hans Erich Lampl Arne Brønstad Eivind Einar Berg RICHARD DEHMEL Dieter Kriszat Tom Olsen Hjørdis Fodstad OLA HANSSON Peter Saul Hassa Horn jr. Ingeborg Sandberg LAURA MARHOLM Merete Jørgensen Håvard Skoglund Marianne Schjetne Trygve Fett Margareth Toften Erik Disch Nina Aabel Pianist: Einar Henning Smedby Peter Plenne Pianist: Harry Andersen We also wish to thank the men, women and children of Oslo and Åsgårdstrand who appear in this film. -

Classical Images – Greek Pegasus

Classical images – Greek Pegasus Red-figure kylix crater Attic Red-figure kylix Triptolemus Painter, c. 460 BC attr Skythes, c. 510 BC Edinburgh, National Museums of Scotland Boston, MFA (source: theoi.com) Faliscan black pottery kylix Athena with Pegasus on shield Black-figure water jar (Perseus on neck, Pegasus with Etrurian, attr. the Sokran Group, c. 350 BC Athenian black-figure amphora necklace of bullae (studs) and wings on feet, Centaur) London, The British Museum (1842.0407) attr. Kleophrades pntr., 5th C BC From Vulci, attr. Micali painter, c. 510-500 BC 1 New York, Metropolitan Museum of ART (07.286.79) London, The British Museum (1836.0224.159) Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus Pegasus Attic, red-figure plate, c. 420 BC Source: Wikimedia (Rome, Palazzo Massimo exh) 2 Classical images – Greek Pegasus Pegasus London, The British Museum Virginia, Museum of Fine Arts exh (The Horse in Art) Pegasus Red-figure oinochoe Apulian, c. 320-10 BC 3 Boston, MFA Classical images – Greek Pegasus Silver coin (Pegasus and Athena) Silver coin (Pegasus and Lion/Bull combat) Corinth, c. 415-387 BC Lycia, c. 500-460 BC London, The British Museum (Ac RPK.p6B.30 Cor) London, The British Museum (Ac 1979.0101.697) Silver coin (Pegasus protome and Warrior (Nergal?)) Silver coin (Arethusa and Pegasus Levantine, 5th-4th C BC Graeco-Iberian, after 241 BC London, The British Museum (Ac 1983, 0533.1) London, The British Museum (Ac. 1987.0649.434) 4 Classical images – Greek (winged horses) Pegasus Helios (Sol-Apollo) in his chariot Eos in her chariot Attic kalyx-krater, c. -

Between Journalism and Fiction: Three Founders of Modern Norwegian Literary Reportage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives This file was downloaded from the institutional repository BI Brage - http://brage.bibsys.no/bi (Open Access) Between journalism and fiction: three founders of modern Norwegian literary reportage Jo Bech-Karlsen BI Norwegian Business School Literary Journalism Studies, 5(2013)1: 11-25 This is an open access journal, peer-reviewed, sponsored by the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies (IALJS) 11 Between Journalism and Fiction: Three Founders of Modern Norwegian Literary Reportage Jo Bech-Karlsen BI Norwegian Business School, Norway The modern origins of literary reportage in Norway can be traced back to the second half of the nineteenth century and a time of uncertain generic boundaries. n the ongoing effort to excavate the different traditions of literary report- Iage globally, Norway has its own history. To understand it I will examine three influential Norwegian reporters with origins in the nineteenth century: A. O. Vinje (1818-1870), Christian Krohg (1852-1925), and Knut Hamsun (1859-1952).1 I have chosen them because they were innovative in their time and worked as reporters for decades. They have “survived”; they are still pres- ent in discussions of journalism in Norway, written about in textbooks and biographies, and admired as models. Indeed, we can consider them to be the founders of the modern Norwegian tradition of literary reportage, a term I use in deference to Norwegian and indeed Continental usage, as opposed to the American usage of literary journalism. Vinje, Krohg, and Hamsun were not only journalists, however.