The Rural Women's Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cradock Four

Saif Pardawala 12/7/2012 TRC Cradock Four Amnesty Hearings Abstract: The Amnesty Hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation show the connection between the South African Apartheid state and the mysterious disappearances of four Cradock political activists. The testimonies of members of the security police highlight the lengths the apartheid state was willing to go to suppress opposition. The fall of Apartheid and the numerous examples of state mandated human rights abuses against its opponents raised a number of critical questions for South Africans at the time. Among the many issues to be addressed, was the need to create an institution for the restoration of the justice that had been denied to the many victims of apartheid’s crimes. Much like the numerous truth commissions established in Eastern Europe and Latin America after the formation of democracy in those regions, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was founded with the aims of establishing a restorative, rather than punitive justice. The goal of the TRC was not to prosecute and impose punishment on the perpetrators of the state’s suppression of its opposition, but rather to bring closure to the many victims and their families in the form of full disclosure of the truth. The amnesty hearings undertaken by the TRC represent these aims, by offering full amnesty to those who came forward and confessed their crimes. In the case of Johan van Zyl, Eric Taylor, Gerhardus Lotz, Nicholas van Rensburg, Harold Snyman and Hermanus du Plessis; the amnesty hearings offer more than just a testimony of their crimes. The amnesty hearings of the murderers of a group of anti-apartheid activists known as the Cradock Four show the extent of violence the apartheid state was willing to use on its own citizens to quiet any opposition and maintain its authority. -

How Women Influence Constitution Making After Conflict and Unrest

JANUARY 2018 RESEARCH REPORT AP Photo / Aimen Zine How Women Influence Constitution Making After Conflict and Unrest BY NANAKO TAMARU AND MARIE O’REILLY RESEARCH REPORT | JANUARY 2018 CONTENTS Executive Summary . 1 Introduction: The Global Context . 3 1 | How Do Women Get Access? . 9 2 | What Impact Do Women Have? . 19 3 | Case Study: Women InfluencingConstitution Reform in Tunisia . 30 4 | Challenges to Women’s Influence . 50 5 | Lessons for Action . 56 Annexes . 61 Acknowledgements . 66 PHOTO ON FRONT COVER | Members of the Tunisian National Constituent Assembly celebrate the adoption of the new constitution in Tunis, January 26, 2014 . How Women Influence Constitution Making t RESEARCH REPORT | JANUARY 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Constitution reform is a frequent feature of peace Despite these hurdles, the cases show that women and transition processes: 75 countries undertook have exerted considerable influence on the decision- constitution reform in the wake of armed conflict, making process, the text of the constitution, and unrest, or negotiated transition from authoritarianism broader prospects for a successful transition to lasting to democracy between 1990 and 2015 . Often peace. Women repeatedly bridged divides in the complementing peace talks, constitutional negotiations negotiating process, contributing to peacebuilding and advance new political settlements, bringing diverse reconciliation in deeply divided societies, while also parties together to agree on how power will be advancing consensus on key issues. They broadened exercised in a country’s future. Increasingly, citizens societal participation and informed policymakers of and international actors alike advocate for participatory citizens’ diverse priorities for the constitution, helping constitution-making processes that include a broader to ensure greater traction for the emerging social cross-section of society—often to address the contract . -

Accessing Information for Better Basic Education

ACCESSING INFORMATION FOR BETTER BASIC EDUCATION South African History Archive - Since 1988 ABOUT THE SOUTH AFRICAN HISTORY ARCHIVE The South African History Archive (SAHA) is an independent human rights archive dedicated to documenting, supporting and promoting greater awareness of past and contemporary struggles for justice in South Africa. Through its Freedom of Information Programme (FOIP) SAHA aims to extend the boundaries of freedom of information in South Africa by: • creating awareness of the right to information and its power as an enabling right that can be used to protect, promote and fulfil other human rights • empowering individuals and organisations to understand and utilise the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) as a strategic advocacy tool • increasing compliance with, and the use of, PAIA For more information about FOIP, please contact: The South African History Archive Box 31719 Braamfontein 2017 Tel: +27117182563 Fax: +27865001600 Web: www.saha.org.za OSF Logo O plus text.pdf 03-Aug-05 11:28:15 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The material in this guide was developed by the South African History Archive (SAHA) as part of a long-term strategy aimed at building the capacity of individuals, communities and organisations to understand and utilise the Promotion of Access to Information Act, 2000 (PAIA) to forward different kinds of struggles for justice in South Africa. SAHA gives permission for this guide to be used and reproduced, with acknowledgement, by all those seeking to better understand and utilise PAIA. CREDITS: This guide was made possible through the generous support of the Open Society Foundation for South Africa and the Atlantic Philanthropies. -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

LEARNING from LEADERS CISSIE GOOL, CHERYL CAROLUS, DESMOND TUTU and NELSON MANDELA Cover Image: © Rashid Lombard

GRADE 4 LEARNING FROM LEADERS CISSIE GOOL, CHERYL CAROLUS, DESMOND TUTU AND NELSON MANDELA Cover image: © Rashid Lombard 2 City of Cape Town LESSON PLAN OVERVIEW: FOR THE EDUCATOR Lesson plan title: Learning from leaders Learning area: Social Science (History) Grade: 4 Curriculum link: Learning from leaders Learning outcomes (LO): These outcomes are Assessment standards (AS) drawn directly from Curriculum Assessment according to CAPS: Policy Statements (CAPS) LO 1: The learner will be able to use inquiry skills AS 2 and 3 to investigate the past and present. LO 2: The learner will be able to demonstrate AS 2 historical knowledge and understanding. LO 3: The learner will be able to interpret AS 3 aspects of history. CONTENT LINKS Looking back at: Current: Looking ahead to: Grade 3: Work Grade 4: Learning Grade 5: Heritage trail covered in Life Skills from leaders Grade 9: Civil resistance Grade 11: Segregation as the foundation for apartheid, and the nature of resistance to apartheid Context: The activities are designed to give learners without (and even those with) access to additional history materials an overview of local leaders of the liberation struggle. The activities will help learners understand what it means to be a good leader. The source material explains that history is not simply about ‘great’ men or women. The content also addresses bullying and children’s rights. The activities and associated source material introduce learners to new concepts and ideas. Educators should determine the time required for learners to complete activities. ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES Activity aims: Learners will be able to make reasonable conclusions about leaders from reading source material, and draw reasoned conclusions about what constitutes good leadership qualities. -

CIVIL RESISTANCE in SOUTH AFRICA, 1970S to 1980S Learning from Leaders Across a Range of Anti-Apartheid Organisations

GRADE 12 CIVIL RESISTANCE IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1970s TO 1980s Learning from leaders across a range of anti-apartheid organisations. Learning from leaders across a range of anti-apartheid organisations Black Sash, Food and Canning Workers Union (FCWU), End Conscription Campaign (ECC) and United Democratic Front (UDF), with reference to Liz Abrahams, Mary Burton, Ashley Kriel, Ivan Toms and Nelson Mandela. Cover image: © Rodger Bosch 2 City of Cape Town LESSON PLAN OVERVIEW: FOR THE EDUCATOR Civil resistance in South Africa, 1970s to 1980s Learning area: Social Science (History) Grade: 12 Curriculum link: Civil resistance in South Africa, 1970s to 1980s Learning outcomes (LO): These outcomes are Assessment standards (AS) drawn directly from Curriculum Assessment according to CAPS: Policy Statements (CAPS) LO 1: Historical inquiry AS 1 to 4 LO 2: Historical concepts AS 1 to 3 LO 3: Knowledge construction and communication AS 1 to 3 CONTENT LINKS: Looking back at: Current: Grade 9: Turning points and civil resistance Grade 12: Civil resistance in South Africa, Grade 11: Segregation as the foundation 1970s to 1980s for apartheid, and the nature of resistance to apartheid Context: The activities are designed to introduce learners without (and even those with) access to additional history materials to civil resistance in the apartheid era. This includes the growing power of the trade union movement, various responses to Botha’s “reforms”, the ECC and Black Sash, and the international anti-apartheid movement’s “Free Mandela” campaign. ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES Activity aims: Learners will learn to: • collect information to fill in the broader picture; • select relevant information; • analyse and weigh up conclusions reached or opinions about events or people from the past; • engage in debate about what happened, and how and why it happened; • use evidence to back up an argument in a systematic way; and • understand that different persons, communities or countries choose to remember the past in a certain way. -

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger

• Joe ALFERS • Peter AUF DER HEYDE • Omar BADSHA • Rodger BOSCH • Julian COBBING • Gille DE VLIEG • Brett ELOFF • Don EDKINS • Ellen ELMENDORP • Graham GODDARD • Paul GRENDON • George HALLETT • Dave HARTMAN • Steven HILTON-BARBER • Mike HUTCHINGS • Lesley LAWSON • Chris LEDOCHOWSKI • John LIEBENBERG • Herbert MABUZA • Humphrey Phakade "Pax" MAGWAZA • Kentridge MATABATHA • Jimi MATTHEWS • Rafs MAYET • Vuyi Lesley MBALO • Peter MCKENZIE • Gideon MENDEL • Roger MEINTJES • Eric MILLER • Santu MOFOKENG • Deseni MOODLIAR (Soobben) • Mxolisi MOYO • Cedric NUNN • Billy PADDOCK • Myron PETERS • Biddy PARTRIDGE • Chris QWAZI • Jeevenundhan (Jeeva) RAJGOPAUL • Wendy SCHWEGMANN • Abdul SHARIFF • Cecil SOLS • Lloyd SPENCER • Guy TILLIM • Zubeida VALLIE • Paul WEINBERG • Graeme WILLIAMS • Gisele WULFSOHN • Anna ZIEMINSKI • Morris ZWI 1 AFRAPIX PHOTOGRAPHERS, BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES • Joe ALFERS Joe (Joseph) Alfers was born in 1949 in Umbumbulu in Kwazulu Natal, where his father was the Assistant Native Commissioner. He attended school and university in Pietermaritzburg, graduating from the then University of Natal with a BA.LLB in 1972. At University, he met one of the founders of Afrapix, Paul Weinberg, who was also studying law. In 1975 he joined a commercial studio in Pietermaritzburg, Eric’s Studio, as an apprentice photographer. In 1977 he joined The Natal Witness as a photographer/reporter, and in 1979 moved to the Rand Daily Mail as a photographer. In 1979, Alfers was offered a position as Photographer/Fieldworker at the National University of Lesotho on a research project, Analysis of Rock Art in Lesotho (ARAL) which made it possible for him to evade further military service. The ARAL Project ran for four years during which time Alfers developed a photographic recording system which resulted in a uniform collection of 35,000 Kodachrome slides of rock paintings, as well as 3,500 pages of detailed site reports and maps. -

Meeting History Face-To-Face a Guide to Oral History Research and Writing: Dr Patricia Watson and Diane Favis

Meeting history face-to-face A guide to oral history Research and Writing: Dr Patricia Watson and Diane Favis Design and Layout: Crisp Media Photographs: Sunday Times (memorial photos), Zweli Gamede, Patricia Watson (school photos), Gille de Vlieg (Driefontein photos). Project director: Lauren Segal Project management: Seitiso Mogoshane, and assisted by Tshidi Semakale Schools project coordinator: Thapelo Pelo Oral history researcher: Tshepo Moloi Oral history transcriber: Plantinah Dire Project Reference Group: Professor Philip Bonner (University of the Witwatersrand) Dr Cynthia Kros (University of the Witwatersrand) Noor Nieftagodien (History Workshop, University of the Witwatersrand), Piers Pigou (Director of the South African History Archives – SAHA, University of the Witwatersrand). Art project management: Monna Mokoena and Lesley Perkes Special thanks to: The Atlantic Philanthropics for funding the SAHA/ Sunday Times School Oral History Project The project partners: The Department of Education, Race and Values Directorate; The South African History Archive; Sunday Times; and Johncom Learning. The Grade 10 and 11 learners who participated in the project from the following schools: Bodibeng Secondary and Brentpark Secondary in Kroonstad; Kgaiso Secondary and Capricorn High in Polokwane; and Mzinoni Secondary in Bethal. The history educators: Faith Mashiya (Bodibeng Secondary, Kroonstad) Giesela Strydom (Brentpark Secondary, Kroonstad), Heleen Pearsnall (Capricorn High, Polokwane), Eddie Nkosi (Mzinoni Secondary, Bethal). The Directorate of Race and Values in the Free State Department of Education for the workshop that allowed the book to be trialled. The publishers gratefully acknowledge permission to reproduce copyright material in this publication. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, but if any copyright infringements have been made, SAHA would be grateful for information that would enable any omissions or errors to be corrected in subsequent impressions. -

Celebrating Women in South African History ,, ,, for Freedom and Equality’ Celebrating Women in South African History

The Legacy Series’ ,, ,, For Freedom and Equality’ Celebrating Women in South African History ,, ,, For freedom and equality’ celebrating women in south african history For more information on the role of women in our history The Legacy Series visit www.sahistory.org.za , wathint , ’ abafazi, wathint ’ imbokotho , This Booklet was produced for the Department of you ve tampered with the women 978-1-4315-03903-2 , Basic Education by South African History Online you ve knocked against a rock Foreword - Celebrating the role of women in South African History and Heritage t gives me great pleasure that since I took office i as Minister of Basic Education, my Department is, for the first time, launching a publication that showcases the very important role played by the past valiant and fearless generations of women in our quest to rid our society of patriarchal oppres- sion. While most of our contemporaries across the globe had, since the twentieth century, benefited from the international instruments such as the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights and the Convention for the Elimination of Discrimina- tion against Women (CEDAW), which barred all forms of discrimination, including gender discrimi- nation, we in this Southernmost tip of the African continent continued to endure the indignity of gender discrimination across all spheres of national life. Gender oppression was particularly inhuman Minister Angie Motshekga. during apartheid, where women suffered a triple Source: Department of Basic Education. oppression of race, class and gender. The formal promulgation of the Constitution of the Republic in 1996 was an important milestone, par- ticularly for women, in our new democracy. -

Dark Impact Steven Humblet Imperial Impact Ariella Azoulay Relations

00 Dark Impact 00 The Impact of the Camera on Wheels: Steven Humblet The Moving Gaze in the Modern Subject 00 Imperial Impact Sara Dominici Ariella Azoulay 00 Fashioning an ‘Image Space’ in Apartheid 00 Relations and Representations of Artistic South Africa: Afrapix Photographers’ ‘Impact’ in Rio’s Favelas Collective and Agency Simone Kalkman M. Neelika Jayawardane 00 Shine a Light in Dark Places 00 The Crisis of the Cliché. Has conflict Donald Weber photography become boring? 00 So You Want to Change the World Peter Bouckaert Lewis Bush 00 On Iconic Photography 00 The Reliable Image: Impact and Rutger van der Hoeven Contemporary Documentary Photography 00 Burning Images for Punishment and Change Wilco Versteeg Florian Göttke 00 Radical Intimacies: (Re)Designing the 00 Photographing the Anthropocene Impact of Documentary Photography Taco Hidde Bakker Oliver Vodeb 00 Break the Cycle. Latin American 00 Imagining Otherwise: The impact of photobooks and the audience aesthetics in an ethical framework Walter Costa Chris Becher and Mads Holm 00 What if We Stopped Claiming the Photobook? 00 Reclaiming Political Fires in Bangladesh. Stefan Vanthuyne Interview Shahidul Alam Shadman Shahid 00 Antwerpen Alberto García del Castillo 00 A Letter to Dr. Paul Julien. Pondering the Photographic Legacy of a Dutch ‘Explorer of Africa’ Andrea Stultiens 00 The Impact of the White, Male Gaze Andrew Jackson and Savannah Dodd 2 Titel 3 The first meaning of ‘impact’ refers to a forceful a genuine belief in the power of images to sway Preface striking of two bodies against each other—a Dark public opinion. Photographs are here supposed to collision, simply put. -

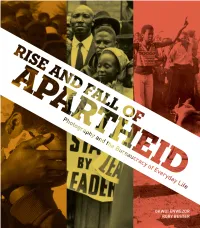

Rise and Fall of Apartheid

Events in the 1980s represent a significant coming to In light of these sweeping global changes, the scene in RISE AND FALL OF APARTHEID terms with the apartheid state at every level.8 It is within this Cape Town on that day in parliament can be properly encap- PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE BUREAUCRACY OF EVERYDAY LIFE context that the Detainees’ Hunger Strike at Diepkloof Prison sulated as an appointment with history. The announcement Okwui Enwezor in Soweto, which started on January 23, 1989, was pivotal in of the end of apartheid was part of a carefully choreographed F. W. de Klerk’s act of rapprochement that occurred a year lat- and coordinated plan: first the unbanning of the African Na- er. The strike appeared to be the trigger that finally brought tional Congress (ANC), Pan-African Congress (PAC), South Apartheid is Violence. Violence is used to subjugate and to deny basic rights to black people.1 But no matter how the policy of the apartheid government to the table for serious negotiation. African Communist Party (SACP), Congress of South African apartheid has been applied over the years, both black and white democrats have actively opposed it. It is in the struggle for Twenty prisoners detained under the 1986 state of emergen- Trade Unions (COSATU), and other political, labor, and civic justice that the gulf between artists, writers, and photographers and the people has been narrowed. cy laws began a hunger strike with an unequivocal demand: organizations; the lifting of the state of emergency; and the —Omar Badsha, South Africa: The Cordoned Heart, 1986 the unconditional release of all political prisoners. -

1980S: Women Organise Botha Made a Desperate Effort to Make Reforms by Introduc- Ing a New Constitution and Created the Tricameral Parliament

1980s: Women organise Botha made a desperate effort to make reforms by introduc- ing a new constitution and created the Tricameral Parliament. Three parliaments were set up - one each for those classified n the 1980s, the context of resistance changed. Interna- as ‘white’, ‘coloured’ and Indian. However, this was widely re- i tional opposition to apartheid had grown and interna- jected by ‘coloured’ and Indian people and seemed doomed tional boycotts of Apartheid South Africa were under way. to fail from the start. Opposition took many forms - many countries had economic Press freedom was more strictly restricted. Resistance contin- sanctions against South Africa, the foreign investment in the ued, with ethnic conflict and struggles between hostel and country began to decline and sporting boycotts restricted town dwellers adding to the turmoil. In an attempt to deal the country’s participation in international events. Internal with the escalating protests, the government implemented resistance organizations had also grown and become more successive States of Emergency during which many people militant, and there were more alliances across race and class were detained and organisations restricted. About 1% of barriers. Rioting, protests and confrontations with police and the 050 people detained in 1986/87 were women and girls. the army were occurring on an almost daily basis. Some of these women were tortured. Pregnant women were From the end of the 1970s, women were integrated into many often assaulted, which led to miscarriage. Body searches, aspects of the liberation struggle. They occupied positions of vaginal examinations and other humiliating procedures also leadership in political organisations and trade unions and occurred, and were all reported by former detainees at the played prominent roles.