The Characterization of the Borg in Star Trek: the Next Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene Roddenberry: the Star Trek Philosophy

LIVING TREKISM – Database Gene Roddenberry: The Star Trek Philosophy "I think probably the most often asked question about the show is: ‘Why the Star Trek Phenomenon?’ And it could be an important question because you can ask: ‘How can a simple space opera with blinking lights and zap-guns and a goblin with pointy ears reach out and touch the hearts and minds of literally millions of people and become a cult in some cases?’ Obviously, what this means is, that television has incredible power. They’re saying that if Star Trek can do this, then perhaps another carefully calculated show could move people in other directions – as to keep selfish interest to creating other cults for selfish purposes – industrial cartels, political parties, governments. Ultimate power in this world, as you know, has always been one simple thing: the control and manipulation of minds. Fortunately, in the attempt however to manipulate people through any – so called Star Trek Formula – is doomed to failure, and I’ll tell you why in just a moment. First of all, our show did not reach and affect all these people because it was deep and great literature. Star Trek was not Ibsen or Shakespeare. To get a prime time show – network show – on the air and to keep it there, you must attract and hold a minimum of 18 million people every week. You have to do that in order to move people away from Gomer Pyle, Bonanza, Beverly Hill Billies and so on. And we tried to do this with entertainment, action, adventure, conflict and so on. -

Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 1986 Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek" Mary Jo Deegan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Deegan, Mary Jo, "Sexism in Space: The rF eudian Formula in "Star Trek"" (1986). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 368. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/368 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THIS FILE CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING MATERIALS: Deegan, Mary Jo. 1986. “Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in ‘Star Trek.’” Pp. 209-224 in Eros in the Mind’s Eye: Sexuality and the Fantastic in Art and Film, edited by Donald Palumbo. (Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, No. 21). New York: Greenwood Press. 17 Sexism in Space: The Freudian Formula in IIStar Trek" MARY JO DEEGAN Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of the starship Enterprise, its five year mission to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before. These words, spoken at the beginning of each televised "Star Trek" episode, set the stage for the fan tastic future. -

Creating “Star Trek CATAN – Federation Space”

Creating “Star Trek CATAN – Federation Space” After Star Trek Catan was so well received, and as many of you asked us to take this joint venture of the two franchises Catan and Star Trek even further towards the “Final Frontier,” we thought long and hard about what kind of game expansion you would enjoy. As we knew that a lot of players liked our Catan Geographies™ maps so much, which take the whole Settlers of Catan experience towards a real map to put settlements in, we thought: Let us take Star Trek Catan into a “real” region of space to put our little NCC-1701 spaceships in. The crucial question was: Is there a region of space sufficiently “real” inside the Star Trek – The Original Series time period? After a bit of research, we discovered this wonderful map titled “The Explored Galaxy” over at the Memory Alpha wiki. As it turned out, this was “as real as it could get,” as it had been first shown hanging on a wall in none other than Captain James T. Kirk’s quarters in the Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country motion picture (and subsequently in various episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation). Every true Star Trek fan knows that this particular map depicts a lot of the known and beloved locations shown in The Original Series of the 60s, and some of those from The Animated Series of the 70s. We took great effort to investigate and cross-reference all these depicted celestial bodies with their respective episodes. © CATAN GmbH - Page 1 We then added a couple of planets that were not actually shown on this map but that we would really want to have in our game, and tried to pinpoint their locations according to mostly in-canon and sometimes semi-canon sources. -

Abstracts and Backgrounds

Abstracts and Backgrounds NAVY Con TABLE OF CONTENTS DESTINATION UNKNOWN ................................................................................. 3 WAR AND SOCIETY ............................................................................................. 5 MATT BUCHER – POTEMKIN PARADISE: THE UNITED FEDERATION IN THE 24TH CENTURY ............ 5 ELSA B. KANIA – BEYOND LOYALTY, DUTY, HONOR: COMPETING PARADIGMS OF PROFESSIONALISM IN THE CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS OF BABYLON 5 ............................................ 6 S.H. HARRISON – STAR CULTURE WARS: THE NEGATIVE IMPACT OF POLITICS AND IMPERIALISM ON IMPERIAL NAVAL CAPABILITY IN STAR WARS ................................................................................ 6 MATTHEW ADER – THE ARISTOCRATS STRIKE BACK: RE-ECALUATING THE POLITICAL COMPOSITION OF THE ALLIANCE TO RESTORE THE REPUBLIC ......................................................... 7 LT COL BREE FRAM, USSF – LEADERSHIP IN TRANSITION: LESSONS FROM TRILL .......................... 7 PAST AND FUTURE COMPETITION ................................................................ 8 WILLIAM J. PROM – THE ONCE AND FUTURE KING OF BATTLE: ARTILLERY (AND ITS ABSENCE) IN SCIENCE FICTION .......................................................................................................................... 8 TOM SHUGART – ALL ABOUT EVE: WHAT VIRTUAL FOREVER WARS CAN TEACH US ABOUT THE FUTURE OF COMBAT ................................................................................................................... 10 -

Download the Borg Assimilation

RESISTANCE IS FUTILE… BORG CUBES Monolithic, geometric monstrosities capable of YOU WILL BE ASSIMILATED. defeating fleets of ships, they are a force to be Adding the Borg to your games of Star Trek: Ascendancy feared. introduces a new threat to the Galaxy. Where other civilizations may be open to negotiation, the Borg are single-mindedly BORG SPIRES dedicated to assimilating every civilization they encounter into Borg Spires mark Systems under Borg control. the Collective. The Borg are not colonists or explorers. They are Over the course of the game, Borg Spires will build solely focused on absorbing other civilizations’ technologies. new Borg Cubes. The Borg are not controlled by a player, but are a threat to all the forces in the Galaxy. Adding the Borg also allows you to play BORG ASSIMILATION NODES games with one or two players. The rules for playing with fewer Borg Assimilation Nodes are built around Spires. Built than three players are on page 11. Nodes indicate how close the Spire is to completing a new Borg Cube and track that Borg System’s current BORG COMPONENTS Shield Modifier. • Borg Command Console Card & Cube Card BORG TECH CARDS • 5 Borg Cubes & 5 Borg Spires Players claim Borg Tech Cards when they defeat • 15 Borg Assimilation Nodes & 6 Resource Nodes the Borg in combat. The more Borg technology you • 20 Borg Exploration Cards acquire, the better you will fare against the Borg. • 7 Borg System Discs • 20 Borg Technology Cards BORG COMMAND CARDS • 30 Borg Command Cards Borg Command Cards direct the Cubes’ movement • 9 Borg Dice during the Borg’s turn and designate the type of System each Cube targets. -

'Star Trek' Actors Head for Videogame Frontier 6 June 2012

'Star Trek' actors head for videogame frontier 6 June 2012 The actors who played Captain James T. Kirk and lead game producer Brian Miller. Spock in the 2009 film reboot of "Star Trek" will give voice to those characters in a videogame "Kirk and Spock find themselves in an incredibly based on the beloved science fiction franchise. challenging amount of mayhem as they confront the Gorn throughout the game." Paramount Pictures and game publisher NAMCO BANDAI Games America Inc. announced on The game is being developed by Canada-based Tuesday that Chris Pine and Zachary Quinto will studio Digital Extremes, according to NAMCO. reprise their roles from the "Star Trek" film directed by J.J. Abrams. (c) 2012 AFP "We are thrilled to have these incredible actors lending their voice to the legendary characters of Kirk and Spock in the videogame realm," said LeeAnne Stables, head of Paramount's videogame unit. "Players are in for a truly authentic experience." The "Star Trek" videogame is scheduled for release early next year, with versions tailored for play on Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 videogame consoles as well as on personal computers powered by Windows software. "There are certain elements at the core of Star Trek -- insurmountable odds, exploration, villains like the Gorn and heroes like Kirk and Spock," said NAMCO vice president of marketing Carlson Choi. "Our goal is to pull gamers as deep into the Star Trek universe as possible and an integral part of that is the talent that makes these characters their own." An original storyline for the game was being created by Marianne Krawczyk, a writer known for her work on the hit "God of War" videogame franchise, and people working on an upcoming "Star Trek" film, according to Paramount. -

Hasbro's KRE-O STAR TREK Beams Into the Toy Aisle with New Building Sets and a Stop Motion Digital Short Produced by Bad Robot

May 7, 2013 Hasbro's KRE-O STAR TREK Beams into the Toy Aisle with New Building Sets and a Stop Motion Digital Short Produced by Bad Robot The Digital Short, Utilizing KRE-O STAR TREK Building Sets Now On Shelves, Will Make its TV Broadcast Premiere May 13 on Cartoon Network PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS), announced the availability of the new KRE-O STAR TREK line at retail locations beginning today. Also releasing today is a stop motion animated short featuring KRE-O building sets and KREON figures based on the iconic STAR TREK film franchise. Fans can watch the video, with a new stand-alone STAR TREK storyline, now on the official KRE-O YouTube channel at youtube.com/KREO. The digital short will make its television broadcast premiere May 13 at 7:30 p.m. EST on Cartoon Network. The KRE-O STAR TREK stop motion digital short animation was produced through film director J.J. Abrams' production company, Bad Robot, with special effects for the piece created by Kelvin Optical, one of the visual effects teams also working on the soon-to-be released STAR TREK INTO DARKNESS from Paramount Pictures. "KRE-O STAR TREK marks the first time the STAR TREK universe has been available as building sets, and we are thrilled to show off the universe of KRE-O STAR TREK building sets and KREON figures with this exciting stop motion digital short from the Bad Robot team," says Kim Boyd, KRE-O senior brand director for Hasbro. "We're especially excited that kids The KRE-O STAR TREK U.S.S. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

NX Class Cruiser Introductory Guide

THE NX CLASS CRUISER AN INTRODUCTORY GUIDE Edited by: Chris Wallace Published by Panda Press Interstellar Masthead CHIEF EDITOR AND PUBLISHER Admiral Chris Wallace, Ret. TECHNICAL EDITOR Fio Piccolo LAYOUT CONSULTANT Sakura Shinguji Panda Press Interstellar PROJECT COORDINATOR Alison Walters DATA ANALYST Kiki Murakami GRAPHICS Commodore David Pipgras Region Five Office of Graphic Design SENIOR CONSULTANTS Doctor Bernd Schneider, PhD. Commodore Masao Okazaki This document and its entire contents Copyright © 2002 Panda Productions. All rights reserved. We request that no part of this document be reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored on any electronic server (ftp or http) without the written permission of the publishers. Permission to make on printout for personal use is granted. This document includes artwork from other sources. Where possible, permission has been obtained to use them in this document. Any display of copyrighted material in the document is not intended as an infringement of the rights of any of the copyright holders. This is a publication of Panda Productions, Post Office Box 52663, Bellevue, Washington, 98015- 2663. Created and published in the United States of America. NX Class Introductory Guide As the first ships in Starfleet service with a drive capable of sustained Warp 5 operation, the four vessels of the NX class are expected to immediately expand the “envelope” of exploration. Stellar charts provided by the Vulcans show almost 10,000 worlds within 1 year’s travel of Earth. Ships of the NX class mount the most advanced equipment available on Earth and are expected to give decades of fine service. -

STAR TREK the TOUR Take a Tour Around the Exhibition

R starts CONTents STAR TREK THE TOUR Take a tour around the exhibition. 2 ALL THOSE WONDERFUL THINGS.... More than 430 items of memorabilia are on show. 10 MAGIC MOMENTS A gallery of great Star Trek moments. 12 STAR TREK Kirk, Spock, McCoy et al – relive the 1960s! 14 STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION The 24th Century brought into focus through the eyes of 18 Captain Picard and his crew. STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE Wormholes and warriors at the Alpha Quadrant’s most 22 desirable real estate. STAR TREK: VOYAGER Lost. Alone. And desperate to get home. Meet Captain 26 Janeway and her fearless crew. STAR TREK: ENTERPRISE Meet the newest Starfleet crew to explore the universe. 30 STARSHIP SPECIAL Starfleet’s finest on show. 34 STAR TREK – THE MOVIES From Star Trek: The Motion Picture to Star Trek Nemesis. 36 STAR trek WELCOMING WORDS Welcome to Star TREK THE TOUR. I’m sure you have already discovered, as I have, that this event is truly a unique amalgamation of all the things that made Star Trek a phenomenon. My own small contribution to this legendary story has continued to be a source of great pride to me during my career, and although I have been fortunate enough to have many other projects to satisfy the artist in me, I have nevertheless always felt a deep and visceral connection to the show. But there are reasons why this never- ending story has endured. I have always believed that this special connection to Star Trek we all enjoy comes from the positive picture the stories consistently envision. -

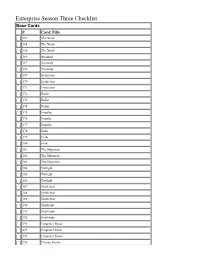

Enterprise Season Three Checklist

Enterprise Season Three Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 163 The Xindi [ ] 164 The Xindi [ ] 165 The Xindi [ ] 166 Anomaly [ ] 167 Anomaly [ ] 168 Anomaly [ ] 169 Extinction [ ] 170 Extinction [ ] 171 Extinction [ ] 172 Raijin [ ] 173 Raijin [ ] 174 Raijin [ ] 175 Impulse [ ] 176 Impulse [ ] 177 Impulse [ ] 178 Exile [ ] 179 Exile [ ] 180 Exile [ ] 181 The Shipment [ ] 182 The Shipment [ ] 183 The Shipment [ ] 184 Twilight [ ] 185 Twilight [ ] 186 Twilight [ ] 187 North Star [ ] 188 North Star [ ] 189 North Star [ ] 190 Similitude [ ] 191 Similitude [ ] 192 Similitude [ ] 193 Carpenter Street [ ] 194 Carpenter Street [ ] 195 Carpenter Street [ ] 196 Chosen Realm [ ] 197 Chosen Realm [ ] 198 Chosen Realm [ ] 199 Proving Ground [ ] 200 Proving Ground [ ] 201 Proving Ground [ ] 202 Stratagem [ ] 203 Stratagem [ ] 204 Stratagem [ ] 205 Harbinger [ ] 206 Harbinger [ ] 207 Harbinger [ ] 208 Doctor's Orders [ ] 209 Doctor's Orders [ ] 210 Doctor's Orders [ ] 211 Hatchery [ ] 212 Hatchery [ ] 213 Hatchery [ ] 214 Azati Prime [ ] 215 Azati Prime [ ] 216 Azati Prime [ ] 217 Damage [ ] 218 Damage [ ] 219 Damage [ ] 220 The Forgotten [ ] 221 The Forgotten [ ] 222 The Forgotten [ ] 223 E2 [ ] 224 E2 [ ] 225 E2 [ ] 226 The Council [ ] 227 The Council [ ] 228 The Council [ ] 229 Countdown [ ] 230 Countdown [ ] 231 Countdown [ ] 232 Zero Hour [ ] 233 Zero Hour [ ] 234 Zero Hour Checklist Cards (1:16 packs) # Card Title [ ] C1 Checklist 1 [ ] C2 Checklist 2 [ ] C3 Checklist 3 MACOs In Action (1:10 packs) # Card Title [ ] M1 Military Assault Command -

Trekonderoga 2018

Special Guests Karl Urban Original Star Trek series fan and New Zealand-born actor Karl Urban actively pursued and won the role of Dr. Leonard McCoy on 2009’s motion picture named, appropriately enough, Star Trek. In his portrayal, Karl evoked many of the subtle mannerisms and vocalisms made famous by one DeForest Kelley of an earlier era – one could consider his performance as an ultimate fan tribute. Karl was interested in acting from a very early age, debuting at age 8 in the New Zealand television series Pioneer Woman. Internationally he appeared in both Hercules: The Legendary Journeys and its spin-off Xena: Warrior Princess, playing recurring roles in both American/New Zealand series. He eventually started working on Hollywood productions and in relatively no time was in big productions such as The Lord of the Rings, The Bourne Supremacy, The Chronicles of Riddick, and Doom. Hollywood press has speculated that he could have landed the role of “James Bond” had not previous film commitments gotten in the way (the role went to Daniel Craig). Other films he appeared in include Red, Dredd, The Loft, Pete’s Dragon, while Karl most recently appeared as “Skurge” in 2016’s Thor: Ragnarok. Karl is active on the convention circuit and makes his first bombshell appearance at this year’s edition of Trekonderoga! Be sure not to miss your opportunity to meet Karl onboard the original Enterprise – where else but in Sickbay, naturally – in a time-defying trip back to the original series sets with today’s Dr. McCoy! Appears Saturday & Sunday only Gates McFadden Not many Enterprise-D characters could call their Captain by his first name, but Doctor Beverly Crusher, memorably played by Gates McFadden, certainly could – and did.