Pdf/Gabrieli Dante E L Oriente.Pdf ———

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 Front-1 Late Front 09.Qxd

y k y cm JUMPING TIME FRAMES VIJAYAN REELS OUT STATS SERIOUS THREAT Actor Shruti Haasan says it was fun to prep Though Covid cases rise in Kerala, CM Vijayan Locust attacks are posing a serious threat for her character, an older woman, in defends state with statistics, saying to food security in parts of East Africa, India and Pak the upcoming film Yaara LEISURE | P2 everything is under control TWO STATES | P7 INTERNATIONAL | P10 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 111 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | WEDNESDAY, JULY 22 | 2020 12 PAGES | `4.00 Airborne transmission ‘distinctly possible’: CSIR AGENCIES idence of airborne spread of "In open spaces, the small- emerging evidence of air- the novel coronavirus. sized droplets get dissipated borne spread after an open New Delhi, July 21: Alluding In a blogpost on CSIR's web- in the air very quickly. letter by over 200 scientists to the emerging evidence, site, Mande referred to findings Moreover, emerging evidence outlined evidence that showed Council of Scientific and of various studies and wrote, also suggests that the encap- floating virus particles can Industrial Research (CSIR) "All these emerging evidences sulated virus in such droplets infect people who breathe chief Shekhar C Mande has and arguments suggest that also gets inactivated by sun- them in. For months, the WHO asserted that airborne trans- indeed airborne transmission light. However, the concen- had insisted that Covid-19 is mission of COVID-19 is indeed of SARS-CoV-2 is a distinct tration of virion-encapsulated transmitted via droplets emit- a "distinct possibility" and ad- possibility." The CSIR chief droplets is likely to be higher ted when people cough or vised people to wear masks advised people to avoid large in places that are not well ven- sneeze. -

51 International Film Festival of India, 2020

51st Hkkjr dk 51ok¡ vUrjkZ"Vªh; fQ+Ye lekjksg] 2020 51st International Film Festival of India, 2020 vkf/kdkfjd foojf.kdk: Hkkjrh; flusek Official Catalogue: Indian Cinema Hkkjr dk 51ok¡ vUrjkZ"Vªh; fQ+Ye lekjksg] xksok 51st International Film Festival of India, Goa TkUkOkjh 16-24, 2021 January 16-24, 2021 vk;kstd & fQYe lekjksg funs'kky; lwpuk vkSj izlkj.k ea=ky;] Hkkjr ljdkj Organized by the Directorate of Film Festivals Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India 001 OFFICIAL CATALOGUE INDIAN CINEMA IFFI 2020 Festival Director: Chaitanya Prasad, Additional Director General Indian Panorama, Indian Sections & Administration: Tanu Rai, Deputy Director Editors: Shambhu Sahu (English), Pankaj Ramendu (Hindi) Assisted by: Kaushalya Mehra, Arvind Kumar, Kamlesh Kumar Rawat Festival Coordinator: Sarwat Jabin, Rudra Pratap Singh, Shyam R Raghavendran, Design & Creative Director: Mukesh Chandra Photograph (Jury): Photo Division Acknowledgements: NFAI/NFDC/Film Producers/Production Houses for providing the films and other related materials. We are also grateful to various film and festival publications/websites, the extracts from which have helped enrich this book. All views expressed in this publication are not necessarily that of the editor or of the IFFI Secretariat. Published by the Directorate of Film Festivals Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Government of India You can visit us at www.iffigoa.org. www.dif.gov.in Hkkjr dk 51ok¡ vUrjkZ"Vªh; fQ+Ye lekjksg] xksok 51st International Film Festival of India, Goa TkUkOkjh 16-24, 2021 January 16-24, 2021 003 UNION MINISTER INFORMATION & BROADCASTING AND ENVIRONMENT, FOREST & CLIMATE CHANGE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MESSAGE I welcome you all to the 51st edition of the International Film Festival of India. -

Orissa High Court Filing Report As on :30/06/2021

ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :30/06/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 1 BLAPL/0004961/2021 MANGAL SINGH MUNDARY BIREN SANKAR TRIPATHY K.BALANG /51 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 2 BLAPL/0004962/2021 DIPTIMAYA SAMANTARAY SATYA RANJAN MULIA DHENKANAL SADAR /403 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 3 BLAPL/0004963/2021 MITHILESH GUPTA SATYA RANJAN MULIA BANARAPAL /186 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 4 BLAPL/0004964/2021 AJIT KUMAR SINGH PRASANNA KUMAR MISHRA S.P.(CID-CRL),CUTTACK /33 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 5 BLAPL/0004965/2021 NABIR SK. @ NOBIR SK. SHAKTI PRASAD DAS JHUMPURA /26 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 6 BLAPL/0004966/2021 TUKUNA SAHU ASHOK KUMAR SARANGI BANTALA /126 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 7 BLAPL/0004967/2021 ABODH KUMAR SETHY SUSHANTA HARICHANDAN / /0 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 8 BLAPL/0004968/2021 SAMI ULLHA SIDDIQUI JAGANNATH KAMILA KORAPUT TOWN /222 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 9 BLAPL/0004969/2021 PRAKASH CHANDRA BEHERA BHABANI SANKAR DAS NUAGAM (DIGAPAHANDI) /125 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 10 BLAPL/0004970/2021 BIJAY MOHANTY DASRATHI DASH SPL.TASK FORCE /15 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 11 BLAPL/0004971/2021 HEMANTA KUMAR BEHERA CHANDAN SAMANTARAY K.NUAGAON /280 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // Page 1/37 ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :30/06/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 12 BLAPL/0004972/2021 GHANASHYAM RANA SATYABRATA PANDA KANTAMAL -

E:\Election Backgrounder\P1-10

SEVENTEENTH GENERAL ELECTIONS TO LOK SABHA ELECTION BACKGROUNDER, ODISHA-2019 Shri Sanjay Kumar Singh, I.A.S Shri Laxmidhar Mohanty, O.A.S(SAG) Commissioner-cum-Secretary Director Shri Subhendra Kumar Nayak, O.A.S(S) Shri Niranjan Sethi Joint Secretary Addl. Director-cum-Joint Secretary Shri Barada Prasanna Das Deputy Director-cum-Deputy Secretary Compilation & Editing Shri Surya Narayan Mishra Shri Debasis Pattnaik Shri Sachidananda Barik Dr. Prasant Kumar Praharaj Co-ordination Shri Biswajit Dash Shri Santosh Kumar Das Shri Prafulla Kumar Mallick Shri Pathani Rout Cover Design Shri Manas Ranjan Nayak DTP & Layout Shri Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Shri Kabyakanta Mohanty Shri Abhimanyu Gouda Published by Information & Public Relations Department Government of Odisha CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD 2. SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA ELECTION, ODISHA, 2019 3. LIST OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES GOING TO POLL (2019) ON PHASE-WISE 4. FACTS AT A GLANCE (SUCCESSIVE GENERAL ELECTIONS) 5. ALL INDIA PARTY POSITION IN LOK SABHA FROM 1951-52 TO 2014 6. VOTES POLLED–SEATS WON ANALYSIS (1996, 1998, 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014) 7. STATE/UT-WISE SEATS IN THE LOK SABHA 8. LOK SABHA ELECTION, ODISHA (1951-52 TO 2014) 9. PARTY-WISE PERFORMANCE IN LOK SABHA ELECTIONS OF ODISHA FROM 1951 TO 2014 10. PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES AFTER DELIMITATION 11. ELECTIONS TO THE SIXTEENTH LOK SABHA, 2014 : ODISHA AT A GLANCE 12. ELECTIONS TO THE SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA, 2019 : ODISHA AT A GLANCE 13. TOTAL NUMBER OF POLLING STATIONS (CONSTITUENCY-WISE) SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA, 2019 14. NUMBER OF ELECTORS IN THE ELECTORAL ROLL 2019 (P.C. / A.C.-WISE) WITH POLLING STATIONS 15. -

$ ^`Cv Urjd W`C CR[ ^R `Vfgcz X

# % B% ! 4)%% 57%<44*=74 " !8 4)%% )-=74 " !8 4)%% ="-/! &' ! &!( )&!*+ ",*!-*./ #<! %"D4 E@2 22F20 20 2 3 3(0 .0 .. 2 0 E 33 0 2 32 3 3 + @ . E @ C%3 ) 9 '$ C 2#7-% 5 88! 7<!% 1$41 7 *7 ( (634&6*,,>8 - ()*+'# , -.& other MLAs in collusion with R the BJP were “hatching a con- shok Gehlot and Sachin spiracy” to topple it,” Gehlot study conducted from June APilot camps got three more alleged without taking the A27 to July 10 by the days to whet their knives before name of Pilot or any other National Center for Disease the Rajasthan High Court party leader. “This is intolera- Control (NCDC) in collabora- declares the winner of the legal ble and condemnable. Those tion with the Delhi bout and leaves the floor open betraying the party will not be Government indicated that a for political bloodletting. able to show their faces in pub- large number of infected per- The court on Tuesday con- lic,” Gehlot added. sons remain asymptomatic. cluded its hearing on petition According to a statement Delhi’s sero-prevalence study filed by the Pilot camp on dis- last one week. issued by Congress chief whip has found that 23.48 per cent qualification notice served by Addressing the Cabinet Mahesh Joshi, Gehlot said of the people have been affect- the Assembly Speaker on 19 meeting Gehlot reiterated that efforts are being made to ed by Covid-19 in the city, rebel MLAs and reserved its a conspiracy to topple his “weaken democracy” in the which has several pockets of judgement till Friday, directing Government was being country but Congress MLAs dense population. -

Fully Com- Andharua on the City’S Outskirts for Mitted to Implement the Project and the Park

y k y cm INSANELY IN LOVE GUNS TRAINED ON STALIN NEW ‘HOPE’ Actor Priyanka Chopra thanks Nick Jonas for DMK president Stalin has said the coronavirus The United Arab Emirates thinking of her all the time and calls spread in Chennai is higher than launched its first mission to Mars Monday herself world’s ‘luckiest girl’ LEISURE | P2 that of China TWO STATES | P7 INTERNATIONAL | P10 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 110 | www.orissapost.com BHUBANESWAR | TUESDAY, JULY 21 | 2020 12 PAGES | `4.00 Bharat Biotech’s city project in deep freeze BISWA BHUSAN MOHAPATRA, OP Bharat Biotech to implement the proj- OPPORTUNITY LOST ect,” said a senior official of IDCO. Bhubaneswar, July 20: The state A Arunachalam, who is in charge government had decided to set up a Foundation stone for the project of BBIL’s Odisha project, has not given biotechnology park on the outskirts of was laid Oct 25, 2009 and again any satisfactory answer for the delay. Nov 16, 2017 the city to make Bhubaneswar a hub “There are many reasons for the delay. for investors in biotechnology. The State govt handed over 65 acres The state government has provided all government identified 65 acres at at Andharua 10 years ago kinds of support. We are fully com- Andharua on the city’s outskirts for mitted to implement the project and the park. Biotech plans to make a vaccine very soon, may be in next two months, Hyderabad-based vaccine major against malaria, injectable polio work will start,” Arunachalam said. Incentives for Bharat Biotech International Ltd vaccine, Covid-19 human papil- Asked about the present status of the (BBIL), a front runner in Covid vaccine loma vaccine in first phase project, he said, “We have got required programme, was chosen as an anchor approval from the State Pollution tenant for the project. -

Orissa High Court Filing Report As on :08/05/2020

ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :08/05/2020 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 1 BLAPL/0003062/2020 NANDAKISHORE NAYAK R.C.BARIK CHANDAKA P.S. /136 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 2 BLAPL/0003063/2020 SADIK MOHAMMED @ SK SADIK MOHAMMEDPRAVASH CHANDRA JENA JALESWAR /89 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 3 BLAPL/0003064/2020 AVIK MAITY PRAVASH CHANDRA JENA JALESWAR /89 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 4 BLAPL/0003065/2020 SUBASH CH. KHUNTIA @ SUBASH CHANDRA RAJENDRA.N.ROUTKHUNTIA KUAKHIA /68 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 5 BLAPL/0003066/2020 JITU PRADHAN @ JITENDRA PRADHAN JYOTIRMAYA SAHOO CHATRAPUR /13 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 6 BLAPL/0003067/2020 SUMANTA BALIARSINGH JYOTIRMAYA SAHOO ADVA /13 /2006 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 7 BLAPL/0003068/2020 PRAVEEN PASWAN MANORANJAN PADHY SUNABEDA /209 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 8 BLAPL/0003069/2020 BHAGIRATHI SAHU PRAKASH KUMAR MISHRA RAMBHA (KHALLIKOTE) /284 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 9 BLAPL/0003070/2020 BIDYADHAR BEHERA KASHINATH PATTNAIK DHENKANAL SADAR /355 /2018 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 10 BLAPL/0003071/2020 RAJENDRA SAMAREDY MANORANJAN PADHY NANDAPUR /60 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 11 BLAPL/0003072/2020 ANANTA SINGH ASHOK KUMAR SAHOO PATTAMUNDAI /316 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // Page 1/22 ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :08/05/2020 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 12 BLAPL/0003073/2020 KRISHNA GUPTA @ KENIYA DEVASHIS PANDA -

About Baripada College in a Nut Shell

Self Study Report of Baripada College, Baripada-2................................ 1 About Baripada College in a nut shell.... Baripada College is an institute with a human face. The history of Baripada College is the history of expansion of knowledge and education in North Odisha. At a time when there was no such wide spread of college education and people had to send their children to the outside for higher education, there came a group of intellectuals to establish a college in the name of Baripada College in the heart of the town. Baripada College is on the threshold of celebrating of its 34 years eventful existence in 2015. The college was started with I.A. class in 1981 affiliated to Utkal University, Bhubaneswar. Today Baripada College has transformed itself from budding institute into a value based high quality college over a period of time. The learning environment, rich academic resources and high intellectual capital base provide the right ambience and perfect platform for developing a bright young mind into a dynamic and socially conscious citizen of India. The college as a pioneer institute takes every effort to imbibe the values of social sensitivity, ethical courage and self tride motivation among students. Walking along the corridors of history with much ups and downs, the college has been accreditated by NAAC with ‘B’ Grade with CGPA of 2.23 in 2009. Now the college is fortunate enough to face 2nd cycle of NAAC accreditation with its newly built up academic blocks, Library- cum-Reading Room, Boys’ Hostel, Women’s Hostel and many more infrastructural set up. -

Prof. Sudhakar Panda Finance Department–Annexe Building, Chairman State Secretariat, Bhubaneswar State Finance Commission, Telephone – (0674)-2391598 – Off

Prof. Sudhakar Panda Finance Department–Annexe Building, Chairman State Secretariat, Bhubaneswar State Finance Commission, Telephone – (0674)-2391598 – Off. Orissa Dated the, 27th January, 2010 To His Excellency, the Governor of Orissa Bhubaneswar. Sir, The Third State Finance Commission was constituted under Article 243 -I of the Constitution of India read with sections 3 & 8 of the Orissa Finance Commission (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act, 1993, (Orissa Act 28 of 1993) on 10th September, 2008 by His Excellency, the Governor of Orissa (Vide Notification No.41424/F Dt.10.9.2008 of Finance Dept.).The Commission started functioning from 1st October, 2008 and submitted the 1st Report (interim) meant for the Thirteenth Finance Commission to His Excellency, the Governor on 9th February, 2009. The Commission was asked to make recommendation relating to the following matters: (i) The principles which should govern- (a) the distribution between State and Panchayati Raj Institutions and the Municipalities of the net proceeds of taxes, duties, tolls and fees leviable by the State which may be divided amongst them under Part-IX and Part-IX A of the Constitution and the allocation between the Panchayats at all levels and Municipalities of their respective shares of such proceeds, (b) the determination of taxes, duties, tolls and fees which may be assigned to, or appropriated by Grama Panchayats, Panchayat Samities and Zilla Parishads or the case may be, Municipalites and (c) the Grants-in-aid to Grama Panchayats, Panchayat Samities, Zilla Parishads or as the case may be, Municipalities from the Consolidated Fund of the State; (ii) the measures needed to improve the financial position of the Grama Panchayats, Panchayat Samities, Zilla Parishads and Municipalities; (iii) any other matters, which the Governor may refer to the Commission in the interest of sound finance of Grama Panchayats, Panchayat Samities, Zilla Parishads and Municipalities. -

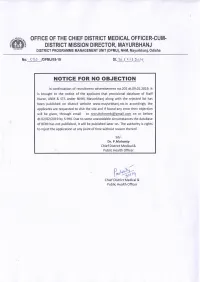

Notige for No Objegtion

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF DISTRICT MEDICAL OFFICER.CUM. -w DISTRICT MISSION DIRECTOR, MAYURBHANJ DISTRICT PROGRAMME MANAGEMENT UNIT (DPMU), NHM, Mayurbhanj, Odisha No. f4 d /DPMU/18-19 Dt.3_t:)_t_a)q NOTIGE FOR NO OBJEGTION In continuation of recruitment advertisement no.202 dt.09.01.2019. lt is brought to the notice of the applicant that provisional database of Staff Nurse, ANM & STS under NHM, Mayurbhanj along with the rejected list has been published on district website www.mayurbhanj.nic.in accordingly the applicants are requested to visit the site and if found any error then objection will be given, through email to [email protected] on or before dt.O2/02/2019 by 5 PM. Due to some unavoidable circumstances the database of BDM has not published, it will be published later on. The authority is rights to reject the application at any point of time without reason thereof. sd/_ Dr. P.Mohanty Chief District Medical & Public Health Officer ./ ?^^re'Y<,^ lrrv ..-3o,1 r"( Chief District Medical & Public Health Officer PROVISIONAL DATABASE OF THE CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF STAFF NURSE UNDER NHM, MAYURBHANJ Educational Qualification HSC/ Equivalent CHSE (Excluding 4th Extra Optional) GNM/B.SC Nursing Number of Years Name & Address Remark Stream Working as Sl. No GNM Regd. 7th/HSC Full Mark Mark (OH/VI/HI) Full Mark % of Mark % of (Science/Art % of No ASHA Knowledg Full Mark in Secured in Application No. Mark in Secured Secured Secured in Secured s/Commerc Secured (Registratio DOB (dd/mm/yyyy) e in Odia in C.H.S.E GNM/B.Sc GNM/B.Sc Physically Challenged H.S.C. -

Orissa High Court Filing Report As on :11/08/2021

ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :11/08/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 1 BLAPL/0006541/2021 SAMBARIA DAS JYOTIRMAYA SAHOO PURUSHOTTAMPUR /147 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 2 BLAPL/0006542/2021 E. SAROJ KUMAR SENAPATI JYOTIRMAYA SAHOO PURUSHOTTAMPUR /211 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 3 BLAPL/0006543/2021 SUSANTA PRADHAN MANORANJAN ACHARYA RANPUR /123 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 4 BLAPL/0006544/2021 RANA BHADRA MD. BANI ISRAIL EOW,BHUBANESWAR /1 /2018 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 5 BLAPL/0006545/2021 BIRENDRA NAIK SUSHANTA KU JOSHI PATNAGARH /128 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 6 BLAPL/0006546/2021 RABI MURMU SOUBHAGYA KUMAR DASH GHASIPURA /118 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 7 BLAPL/0006547/2021 GURUDEV SINGH BHABANI SHANKAR DASPARIDA JODA /109 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 8 BLAPL/0006548/2021 MUNA KHILAR BHABANI SHANKAR DASPARIDA ANGUL TOWN /354 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 9 BLAPL/0006549/2021 BABU @ SASHI BHUSAN PRADHAN BHABANI SHANKAR DASPARIDA SORO /254 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 10 BLAPL/0006550/2021 SAMBARU SIRIKA DIPTI RANJAN BHOKTA SEMILLIGUDA /27 /2012 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 11 BLAPL/0006551/2021 MASHI MUNDA MALAYA KUMAR SWAIN K.BALANG /34 /2019 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // Page 1/60 ORISSA HIGH COURT FILING REPORT AS ON :11/08/2021 SL FILING NO NAME OF PETNR./APPEL COUNSEL FOR PETNR./APPEL PS CASE/LOWER COURT CASE/DISTRICT 12 BLAPL/0006552/2021 BAYA @ SAROJ KUMAR DAS DEEPAK KUMAR SAHOO MARSHAGHAI /285 /2021 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 13 BLAPL/0006553/2021 RANJIT DAS DHIRENDRA KUMAR MOHAPATRA RAJGANGPUR /402 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 14 BLAPL/0006554/2021 RINKU @ RAHUL SAHU SANGRAM KESHARI ROUT HIRAKUD /2 /2017 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 15 BLAPL/0006555/2021 SWADHIN NAIK SUSANTA KUMAR ROUT JEYPORE SADAR /229 /2020 VS VS () STATE OF ODISHA // 16 BLAPL/0006556/2021 PRABHAKAR MUDILI @ PABANI R.N.MOHANTY LINGARAJ P.S. -

The Year in Which the COVID-19 Pandemic Held the World in a Deadly Grip Has Also Left Behind Some Memories to Cherish

POSTAL REGD. NO. BN/237/20-22 RNI REGD. NO. ODIENG/2013/51524 Vol-8, Issue-10 january, 2021 BhuBaneswar PAGES 40 PRICE `20 MOVING AHEAD...TOGETHER FLASH B CK THE YEAR IN WHICH THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HELD THE WORLD IN A DEADLY GRIP HAS ALSO LEFT BEHIND SOME MEMORIES to CHERISH FOLLOW @MyCityLinks @MyCityLinks @MyCityLinks.in @MyCityLinks www.mycitylinks.in CovER | STORY www.mycitylinks.in MOVING AHEAD...TOGETHER Vol-8, Issue-10 january, 2021 BhuBaneswar EDITOR'S DESK Group Editor: Sandeep Mishra Consulting Editor: Vinay Jha As 2021 Beckons, Some Positive Takeaways Editor: Satyabrat (Sanu) Ratho From A Year That One Would Want To Forget Senior Associate Editor: Dikhya Tiwari S one looks back at 2020, nothing Swasti Singh has been pedaling her way to Associate Editor: defines the year better than what glory since she burst onto the cycling scene in made headlines more often than 2015. From making a mark at the state level to Monojit Dasgupta not - the COVID-19 pandemic. winning her first national title in 2018, her early Publisher : Yet, there were moments, includ- years in the sport laid the foundation for what Sameer Hans ingA several even as the pandemic raged on, that would soon turn into an impressive career. The Chief Content Supervisor: make one believe that the year was not entirely 17-year-old sensation is our Sportsperson of the Debi Prasad Sahu about doom and gloom. In our Cover Story, we Month. look at some of these moments which made Odi- The Kalinga Stadium Sports Complex has Reporters: sha and its people proud.