Patagonia: Range Management at the End of the World Guillermo E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

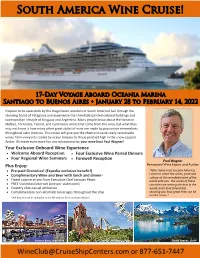

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Port Vision 2040 Port Vision Bahía Blanca 2040

Port Vision 2040 Port Vision Bahía Blanca 2040 Vision developed for the Port Authority of Bahía Blanca by and in collaboration with stakeholders of the Port Industrial Complex. "We do not inherit the land of our parents; we borrow it from our children." Francisco Pascasio Moreno We, the people from Argentina, have the responsibility to unlock our potential as a Nation, improving our present situation and overcoming the difficulties that we face. Thus, the only possible way is looking ahead to envision the future we want to leave for the generations to come and formulating the plans that will bring us closer to that vision. Therefore, it is time to work for the long-term, without neglecting the needs of the short- and medium-term. Here at the Port Authority of Bahía Blanca, we want contribute to achieve that goal. Consequently, we decided to start this long-term planning process, which includes the development of the Port Vision 2040; as we strongly believe that the port is one of the cornerstones for the expansion and prosperity of Bahía Blanca and the region. Thereafter, it is in the balanced combination of people, profit and planet that we foresee the necessary elements for a sustainable development. Moreover, stakeholder engagement is considered an essential factor to realise this long-term vision for attaining a general agreement of the steps to take. Port Vision Bahía Blanca 2040 represents the combined efforts and work of the Port Authority of Bahía Blanca, of most of the stakeholders, and of the institutions that yearn for a growing region and country. -

P a M P a S L I

bs.as argentina www.pampaslife.com pampas life catalogue - 2013 - catalogue pampas life our story 04 our knives 05 06 the patagonia 12 the andes 18 the gaucho 24 the ombu 28 the pulperia 34 the iguazu 38 the rio de la plata contact 43 - 01- inspiration Las Pampas, Argentina 1800s - summer mansions, polo matches, afternoon tea and conversations about worldly travels were all common facets of an affluent life in Buenos Aires during this time. Having a “country” home was your only escape from the heat and hustle and bustle of the city; it was also a vital aspect of your social life. Entertaining with grand parties, lavish weekends and a very posh life style were essential. After all Buenos Aires was one of the most powerful cities in the world at this time. Of course, only the best was demanded and provided, and most of the style and goods were imports from Western Europe. However, when it came to leather and horses no one could do it better than the Argentines. Horses, their tack and their sports (polo, racing and jumping) were important to business life and for the leisure life. And the men who trained and cared for these prestigious animals were treated with a great amount of respect, for they were not only care takers, but amazing craftsman who developed beautiful pieces by hand – horse bridles, stirrups, boots, belts and knives. Over the years, these men, which carry the name gaucho, became known for their craftsmanship with metals and leathers. Still today these items are one of Argentina’s treasures where even the royalty from Europe come to seek them out. -

The Record of Miocene Impacts in the Argentine Pampas

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 41, Nr 5, 749–771 (2006) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org The record of Miocene impacts in the Argentine Pampas Peter H. SCHULTZ1*, Marcelo Z¡RATE2, Willis E. HAMES3, R. Scott HARRIS1, T. E. BUNCH4, Christian KOEBERL5, Paul RENNE6, and James WITTKE7 1Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island 02912–1846, USA 2Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de La Pampa, Avda Uruguay 151, 6300 Santa Rosa, La Pampa, Argentina 3Department of Geology, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama 36849, USA 4Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA 5Department of Geological Sciences, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria 6Berkeley Geochronology Center, 2455 Ridge Road, Berkeley, California 94709, USA 7Department of Geology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 02 March 2005; revision accepted 14 December 2005) Abstract–Argentine Pampean sediments represent a nearly continuous record of deposition since the late Miocene (∼10 Ma). Previous studies described five localized concentrations of vesicular impact glasses from the Holocene to late Pliocene. Two more occurrences from the late Miocene are reported here: one near Chasicó (CH) with an 40Ar/39Ar age of 9.24 ± 0.09 Ma, and the other near Bahía Blanca (BB) with an age of 5.28 ± 0.04 Ma. In contrast with andesitic and dacitic impact glasses from other localities in the Pampas, the CH and BB glasses are more mafic. They also exhibit higher degrees of melting with relatively few xenoycrysts but extensive quench crystals. In addition to evidence for extreme heating (>1700 °C), shock features are observed (e.g., planar deformation features [PDFs] and diaplectic quartz and feldspar) in impact glasses from both deposits. -

Atlantic South America Section 1 MAIN IDEAS 1

Name _____________________________ Class __________________ Date ___________________ Atlantic South America Section 1 MAIN IDEAS 1. Physical features of Atlantic South America include large rivers, plateaus, and plains. 2. Climate and vegetation in the region range from cool, dry plains to warm, humid forests. 3. The rain forest is a major source of natural resources. Key Terms and Places Amazon River 4,000-mile-long river that flows eastward across northern Brazil Río de la Plata an estuary that connects the Paraná River and the Atlantic Ocean estuary a partially enclosed body of water where freshwater mixes with salty seawater Pampas wide, grassy plains in central Argentina deforestation the clearing of trees soil exhaustion soil that has become infertile because it has lost nutrients needed by plants Section Summary PHYSICAL FEATURES The region of Atlantic South America includes four What four countries make countries: Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and up Atlantic South America? Paraguay. A major river system in the region is the _______________________ Amazon. The Amazon River extends from the _______________________ Andes Mountains in Peru to the Atlantic Ocean. The _______________________ Amazon carries more water than any other river in _______________________ the world. The Paraná River, which drains much of the central part of South America, flows into an estuary called the Río de la Plata and the Atlantic Ocean. The region’s landforms mainly consist of plains and plateaus. The Amazon Basin in northern Brazil What is the Amazon Basin? is a huge, flat floodplain. Farther south are the _______________________ Brazilian Highlands and an area of high plains _______________________ called the Mato Grosso Plateau. -

A Synoptic Review of US Rangelands

A Synoptic Review of U.S. Rangelands A Technical Document Supporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment Matthew Clark Reeves and John E. Mitchell Reeves, Matthew Clark; Mitchell, John E. 2012. A synoptic review of U.S. rangelands: a technical document supporting the Forest Service 2010 RPA Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-288. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 128 p. Abstract: The Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 requires the USDA Forest Service to conduct assessments of resource conditions. This report fulfills that need and focuses on quantifying extent, productivity, and health of U.S. rangelands. Since 1982, the area of U.S. rangelands has decreased at an average rate of 350,000 acres per year owed mostly to conversion to agricultural and residential land uses. Nationally, rangeland productivity has been steady over the last decade, but the Rocky Mountain Assessment Region appears to have moderately increased productivity since 2000. The forage situation is positive and, from a national perspective, U.S. rangelands can probably support a good deal more animal production than current levels. Sheep numbers continue to decline, horses and goats have increased numbers, and cattle have slightly increased, averaging 97 million animals per year since 2002. Data from numerous sources indicate rangelands are relatively healthy but also highlight the need for consolidation of efforts among land management agencies to improve characterization of rangeland health. The biggest contributors to decreased rangeland health, chiefly invasive species, are factors associated with biotic integrity. Non-native species are present on 50 percent of non-Federal rangelands, often offsetting gains in rangeland health from improved management practices. -

DEL CENTRO NAVAL AÑO 127 VOLUMEN CXXVII MAYO / AGOSTO DE 2009 Nº 824 Boletín Del Centro Naval AÑO 127 -VOL

pliego-tapa.qxp 25/08/2009 11:27 PÆgina 2 Nº 824 Boletín del Centro Naval La República Argentina necesita un rompehielos. AÑO 127 VOLUMEN CXXVII MAYO / AGOSTO DE 2009 / AGOSTO CXXVII MAYO VOLUMEN AÑO 127 BOLETÍN DEL CENTRO NAVAL BOLETÍN DEL CENTRO Inmediaciones de Base Marambio, marzo 2007. Fotografía: Eduardo Falabella AÑO 127 - VOL. CXXVII Nº 824 MAY / AGO DE 2009 pliego-tapa.qxp 25/08/2009 11:28 PÆgina 4 Portada.qxp 25/08/2009 11:32 PÆgina 097 REPÚBLICA ARGENTINA Boletín del Centro Naval FUNDADO EN MAYO DE 1882 NÚMERO 824 VOLUMEN CXXVII MAYO / AGOSTO DE 2009 Florida 801, C1005AAQ Buenos Aires, República Argentina Telefax: (+54 11) 4311-0041. Conmutador: (+54 11) 4311-1011/16 int. 605 E-mail: [email protected] www.centronaval.org.ar www.boletin.centronaval.org.ar Imagen de portada: Corbeta ARA Espora, durante la revista naval del año 2000. Director Miembro de la Asociación de la Prensa Técnica y Especializada Argentina (APTA), Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Fernando P. Amorena desde el 7 de marzo de 1975 Distinciones al Boletín y a quienes en él escriben Presidente Consejo Editorial n Premio APTA/Rizzuto 1989 en la categoría Publicaciones sin fines de lucro Vicealmirante VGM (R) Carlos L. Alfonso n Primer Premio APTA/Rizzuto 1994 en la categoría Publicaciones Oficiales n Premio 1er. Accésit APTA/Rizzuto 1998 en la categoría Publicaciones Oficiales Vocales Consejo Editorial n Reconocimiento al Mérito 2002 Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Alejandro J. Tierno n Reconocimiento a la Trayectoria 2003 Capitán de Navío VGM (R) Oscar D. Cabral n Premio 2do. -

The Magic of Patagonia Holiday Grade

THE MAGIC OF Tour Code: 46300 Grade 5 PATAGONIA Holiday Duration: 15 nights HOLIDAY DATES Travelling through Chile and Argentina to 6th Nov 2019 - 21st Nov 2019 the end of the world... Walking in the awe-inspiring land of Patagonia, an area of uninterrupted lakes, dormant volcanoes and vast tracts of wilderness. HOLIDAY HIGHLIGHTS Admire the spectacular view and immense glaciers of Torres del Paine. See incredible wildlife - Guanacos, condors, rheas. Cross over the Andean watershed. Tango in Buenos Aires. THE MAGIC OF PATAGONIA HOLIDAY GRADE Where the craggy peaks of the Patagonian Andes This is a Grade 5 holiday. It combines walking in the are too steep sided to hold snow, bare rocks pierce Patagonian Andes with a little sightseeing in Buenos the sky. The famous Torres del Paine are perhaps Aires and Santiago, two iconic capital cities. There the most well known example of this. Snowy are plenty of opportunities for walking through mountains are common but here things are beautiful scenery. The walking in all of our different. Patagonian centres is not particularly high altitude. The highest point we reach on the holiday will likely be 1200m at Pliego Tumbado walking from El We begin our Patagonian journey in Buenos Aires Chalten. Paths are generally good underfoot. where we take in all the iconic sights and sounds of However they are sometimes stony and steep for the city, including an unmissable tango night. Then short sections so walking poles can be useful. on to El Chaten for some rewarding walking with magnificent views of Fitzroy and the surrounding peaks. -

Narratives of Patagonian Exploration Mark W

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research Fall 8-2001 Going to nowhere : narratives of Patagonian exploration Mark W. Bell Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Mark W., "Going to nowhere : narratives of Patagonian exploration" (2001). Master's Theses. Paper 1143. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Since its discovery on Magellan's circumnavigation, Patagonia has been treated differently than any other region in the world. Effectively, Patagonia has been left empty or vacated by the North. But this emptiness and blankness have compulsively attracted curious travel writers who have filled the emptiness of Patagonia with self-reflexive projections. From Charles Darwin and W.H. Hudson to Bruce Chatwin and Paul Theroux, Northern commentators have found in Patagonia a landscape that accommodates their desire for self-reflexivity and self-consciousness. Thus, Patagonia has been simultaneously filled and evacuated by the Northern mind. As a result, Patagonia has become increasingly about the self and less about the physical place to the point where Patagonia as a concept has been abstracted and made into a trope or condition. This paper examines the history of Patagonia in literature in English and analyzes how Patagonia has evolved into its modem signification. I certify that I have read this thesis and find that, in scope and quality, it satisfies the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. -

Fire History in Western Patagonia from Paired Tree-Ring Fire-Scar And

Clim. Past, 8, 451–466, 2012 www.clim-past.net/8/451/2012/ Climate doi:10.5194/cp-8-451-2012 of the Past © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Fire history in western Patagonia from paired tree-ring fire-scar and charcoal records A. Holz1,*, S. Haberle2, T. T. Veblen1, R. De Pol-Holz3,4, and J. Southon4 1Department of Geography, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA 2Department of Archaeology and Natural History, College of Asia & the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia 3Departamento de Oceanograf´ıa, Universidad de Concepcion,´ Chile 4Department of Earth System Sciences, University of California, Irvine, California, USA *present address: School of Plant Sciences, University of Tasmania, Hobart 7001, Australia Correspondence to: A. Holz ([email protected]) Received: 2 September 2011 – Published in Clim. Past Discuss.: 10 October 2011 Revised: 25 January 2012 – Accepted: 27 January 2012 – Published: 9 March 2012 Abstract. Fire history reconstructions are typically based recorded by charcoal from all the sampled bogs and at all on tree ages and tree-ring fire scars or on charcoal in sedi- fire-scar sample sites, is attributed to human-set fires and is mentary records from lakes or bogs, but rarely on both. In outside the range of variability characteristic of these ecosys- this study of fire history in western Patagonia (47–48◦ S) in tems over many centuries and probably millennia. southern South America (SSA) we compared three sedimen- tary charcoal records collected in bogs with tree-ring fire- scar data collected at 13 nearby sample sites. -

Y GADWYN (The Link)

Y GADWYN (The Link) News of the Toronto Welsh Community Volume 39; Number 04 / 05 Ebrill / April - Mai / May, 2004 Minister’s Message We've had another great month at Dewi Sant. On Palm Sunday the morning service was extremely well attended. The Tonna Choir from the Neath area of Wales sang during the service. Our own Sheryl Clay joined them for the afternoon concert and we heard some delightful singing. About $1,300 was raised to launch our Renewal Fund. This is a Fund to help celebrate the Centenary of Dewi Sant in 2007. Thank you all for the wonderful presentations made to me at the April 3rd Social Evening. Whenever I search for the time The Watch will be a constant reminder of Dewi Sant. The ladies as usual fed us so well on the Saturday and the Sunday. Again, this Good Friday they will prepare the Church Dinner and on Easter Sunday a Breakfast. I just don't know how they manage. Bless you all. I'm looking forward to the Services and the Gymanfa over the Easter weekend. And then home! It's been an exciting six months - the innovations - the Welsh Beginners Service, the Lunch Bunch, the St David's Celebrations at the Liberty Grand and here in the Church, the new brochure, the films and videos, the Promotion Booth in the Eaton Centre, the numerous Welsh Flags to be seen in Toronto, the new direction signs (Welsh Dragon and all !) at the junction of Yonge Street and Melrose Avenue and more.... To everyone who had a part to play in these projects a million thanks. -

Invaders Without Frontiers: Cross-Border Invasions of Exotic Mammals

Biological Invasions 4: 157–173, 2002. © 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Review Invaders without frontiers: cross-border invasions of exotic mammals Fabian M. Jaksic1,∗, J. Agust´ın Iriarte2, Jaime E. Jimenez´ 3 & David R. Mart´ınez4 1Center for Advanced Studies in Ecology & Biodiversity, Pontificia Universidad Catolica´ de Chile, Casilla 114-D, Santiago, Chile; 2Servicio Agr´ıcola y Ganadero, Av. Bulnes 140, Santiago, Chile; 3Laboratorio de Ecolog´ıa, Universidad de Los Lagos, Casilla 933, Osorno, Chile; 4Centro de Estudios Forestales y Ambientales, Universidad de Los Lagos, Casilla 933, Osorno, Chile; ∗Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +56-2-6862615) Received 31 August 2001; accepted in revised form 25 March 2002 Key words: American beaver, American mink, Argentina, Chile, European hare, European rabbit, exotic mammals, grey fox, muskrat, Patagonia, red deer, South America, wild boar Abstract We address cross-border mammal invasions between Chilean and Argentine Patagonia, providing a detailed history of the introductions, subsequent spread (and spread rate when documented), and current limits of mammal invasions. The eight species involved are the following: European hare (Lepus europaeus), European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), and red deer (Cervus elaphus) were all introduced from Europe (Austria, France, Germany, and Spain) to either or both Chilean and Argentine Patagonia. American beaver (Castor canadensis) and muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) were introduced from Canada to Argentine Tierra del Fuego Island (shared with Chile). The American mink (Mustela vison) apparently was brought from the United States of America to both Chilean and Argentine Patagonia, independently. The native grey fox (Pseudalopex griseus) was introduced from Chilean to Argentine Tierra del Fuego.