Chamorro Diaspora and the Transpacific Home a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual/Media Arts

A R T I S T D I R E C T O R Y ARTIST DIRECTORY (Updated as of August 2021) md The Guam Council on the Arts and Humanities Agency (GCAHA) has produced this Artist Directory as a resource for students, the community, and our constituents. This Directory contains names, contact numbers, email addresses, and mailing or home address of Artists on island and the various disciplines they represent. If you are interested in being included in the directory, please call our office at 300-1204~8/ 7583/ 7584, or visit our website (www.guamcaha.org) to download the Artist Directory Registration Form. TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCIPLINE PAGE NUMBER FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS 03 - 17 VISUAL/ MEDIA ARTS 18 - 78 PERFORMING ARTS 79 - 89 LITERATURE/ HUMANITIES 90 - 96 ART RELATED ORGANIZATIONS 97 – 100 MASTER’S 101 - 103 2 FOLK/ TRADITIONAL ARTS Folk Arts enriches the lives of the Guam community, gives recognition to the indigenous and ethnic artists and their art forms and to promote a greater understanding of Guam’s native and multi-ethnic community. Ronald Acfalle “ Halu’u” P.O. BOX 9771 Tamuning, Guam 96931 [email protected] 671-689-8277 Builder and apprentice of ancient Chamorro (seafaring) sailing canoes, traditional homes and chanter. James Bamba P.O. BOX 26039 Barrigada, Guam 96921 [email protected] 671-488-5618 Traditional/ Contemporary CHamoru weaver specializing in akgak (pandanus) and laagan niyok (coconut) weaving. I can weave guagua’ che’op, ala, lottot, guaha, tuhong, guafak, higai, kostat tengguang, kustat mama’on, etc. Arisa Terlaje Barcinas P.O.BOX 864 Hagatna, Guam 96932 671-488-2782, 671-472-8896 [email protected] Coconut frond weaving in traditional and contemporary styles. -

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage

束 9mm Proceedings ISBN : 978-4-9909775-1-1 of the International Researchers Forum: Perspectives Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage IRCI Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Published by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage 2 cho, Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0802, Japan Tel: +81 – 72 – 275 – 8050 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.irci.jp © International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) Published on 10 March 2020 Preface The International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society was organised by the International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) in cooperation with the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan and the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties on 17–18 December 2019. -

Using a Short Message System to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake Among Chuukese Women in Guam

Using a Short Message System to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake among Chuukese Women in Guam: Lessons Learned from Linking Distance Technology Between Carriers and Using Telehealth Communication in a Cross-Cultural Context Lilnabeth P. Somera PhD; Ana Joy P. Mendez RN, PhD; and Angelina Mummert Abstract Based on the results of previous research,2 a study to test the efficacy of SMS to increase cervical cancer screening among This paper reports on a project aimed at using a short message system (SMS) Pacific Islander women in Guam and Hawai‘i was developed. to increase cervical cancer screening uptake among Chuukese women in Guam. The study in Guam focused on Chuukese women, the biggest It documents the process and identifies the unexpected challenges which led group of migrants from the Federated States of Micronesia to the early termination of the study. Although the original aims of the project were not met, there were some lessons learned about technology incompat- (FSM) in Guam. The FSM 2013-2018 Comprehensive Cancer ibility in the context of Guam’s and the United States’ cell phone technology Control Plan noted that only 6% of eligible women received interface, the cultural nuances of cell phone use in the study population, and Pap tests in Chuuk.3 Chuukese women bear a disproportionate the necessity to follow a protocol for the termination of a project. burden of cervical cancer morbidity and mortality.4,5 The data presented in the Cancer in the US Affiliated Pacific Islands Keywords 2007-2015 indicate that 73% of cervical cancer cases in Guam were diagnosed at advanced stages5 and that Chuukese women SMS, cervical cancer screening, technology challenges comprised a higher proportion of the advanced stage cases based on an unpublished analysis from the Centers for Disease Abbreviations Control and Prevention National Program of Cancer Registries. -

Music in Pacific Island Cultures Instructor's Manual by Sarah H

Music in Pacific Island Cultures Instructor’s Manual by Sarah H. Watts, Ph.D. Chapter 1 Diversity in Pacific Island Music (1) S, C/U Pictorial Timeline The Pacific Island region is an area of the globe that has been impacted substantially by various colonial influences. Explore these influences by choosing a Pacific Island locale and creating a pictorial timeline of outside colonial influences on the region including dates of arrival, intents of mission, and evidence of cross-cultural pollination in music and the arts. Your pictorial timeline may include photographs, drawings, or digital illustrations of important events accompanied by short captions describing each event in more detail. (2) AA Musical Diversity Polynesia is a region that is home to many languages, subcultures, and customs and is described by the authors as “musically diverse.” Are there other regions of the world that boast musical diversity? Research another area in the world that features richness and diversity in its musical expressions and compare/contrast it with Polynesia. Use Resource 1.1 as a guide. Follow up by sharing your findings with a classmate. (3) AA Your Family Tree Polynesian cultures place a great deal of importance on genealogy, that is, the tracing of one’s ancestry in order to understand one’s own history. In the spirit of Polynesian cultures, research and trace your own genealogy back four generations using the template provided in Resource 1.2. Were there any surprises? (4) S, C/U The Power of Words The authors refer to music of the Pacific Island region as logogenic, that is, a view of music that places emphasis on the text rather than the music. -

Download This Volume

Photograph by Carim Yanoria Nåna by Kisha Borja-Quichocho Like the tåsa and haligi of the ancient Chamoru latte stone so, too, does your body maintain the shape of the healthy Chamoru woman. With those full-figured hips features delivered through natural birth for generations and with those powerful arms reaching for the past calling on our mañaina you have remained strong throughout the years continuously inspire me to live my culture allow me to grow into a young Chamoru woman myself. Through you I have witnessed the persistence and endurance of my ancestors who never failed in constructing a latte. I gima` taotao mo`na the house of the ancient people. Hågu i acho` latte-ku. You are my latte stone. The latte stone (acho` latte) was once the foundation of Chamoru homes in the Mariana Islands. It was carved out of limestone or basalt and varied in size, measuring between three and sixteen feet in height. It contained two parts, the tasa (a cup-like shape, the top portion of the latte) and the haligi (the bottom pillar) and were organized into two rows, with three to seven latte stones per row. Today, several latte stones still stand, and there are also many remnants of them throughout the Marianas. Though Chamorus no longer use latte stones as the foundations of their homes, the latte symbolize the strength of the Chamorus and their culture as well as their resiliency in times of change. Micronesian Educator Editor: Unaisi Nabobo-Baba Special Edition Guest Editors: Michael Lujan Bevacqua Victoria Lola Leon Guerrero Editorial Board: Donald Rubinstein Christopher Schreiner Editorial Assistants: Matthew Raymundo Carim Yanoria Design and Layout: Pascual Olivares ISSN 1061-088x Published by: The School of Education, University of Guam UOG Station, Mangilao, Guam 96923 Contents Guest Editor’s Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the Mortgage Market

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | JULY 2021 Data Point: Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the Mortgage Market Using the 2020 HMDA Data 1 This is another occasional series of publications from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Office of Research. These publications are intended to further the Bureau’s objective of providing an evidence-based perspective on consumer financial markets, consumer behavior, and regulations to inform the public discourse. See 12 U.S.C. §5493(d). [1] [1] This report was prepared by Young Jo and Alexandra Dobre. 2 DATA POINT: ASIAN AMERICAN AND PACIFIC ISLANDERS IN THE MORTGAGE MARKET Table of contents Table of contents ..............................................................................................................3 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................4 2. Characteristics of Mortgages .....................................................................................7 3. Characteristics of Borrowers ...................................................................................18 4. Characteristics of Lenders........................................................................................20 5. Conclusion...................................................................................................................22 3 1. Introduction A widely held perception of Asian American and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) as a homogeneous group with high income and education level has contributed -

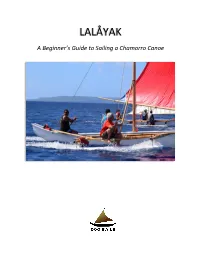

Lalåyak – a Beginner's Guide to Sailing a Chamorro Canoe

LALÅYAK A Beginner’s Guide to Sailing a Chamorro Canoe © 2019 500 Sails. All rights reserved. This project was made possible by support from the Northern Marianas Humanities Council, a non-profit, private corporation funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Northern Marianas Humanities Council will have non-exclusive, nontransferable, irrevocable, royalty-free license to exercise all the exclusive rights provided by copyright. Cover photo: Jack Doyle Pictured left to right: Cecilio Raiukiulipiy, Ivan Ilmova, Pete Perez (close canoe); Sophia Perez, Arthur De Oro, Vickson Yalisman (far canoe) Sail between Saipan and Tinian in Tinian Channel. Aguiguan Island in background. Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Historic Context ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Sakman Design .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sailing Vocabulary ........................................................................................................................................ -

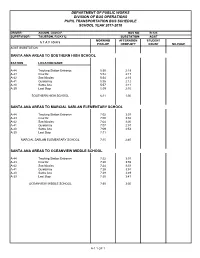

Department of Public Works Division of Bus Operations Pupil Transportation Bus Schedule School Year 2017-2018

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. BUS NO. B-123 SUPERVISOR: TAIJERON, RICKY U. SUBSTATION: AGAT MORNING AFTERNOON STUDENT S T A T I O N S PICK-UP DROP-OFF COUNT MILEAGE AGAT SUBSTATION SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL STATION LOCATION NAME A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 SANTA ANA AREAS TO MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:02 3:03 A-43 Cruz #2 7:00 3:02 A-42 San Nicolas 7:04 3:00 A-41 Quidachay 7:07 2:57 A-40 Santa Ana 7:09 2:53 A-39 Last Stop 7:11 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:15 2:40 SANTA ANA AREAS TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:22 3:57 A-43 Cruz #2 7:20 3:55 A-42 San Nicolas 7:24 3:53 A-41 Quidachay 7:26 3:51 A-40 Santa Ana 7:28 3:49 A-39 Last Stop 7:30 3:47 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:30 A-1 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: BORJA, GARY P. -

Designing a Woman-Friendly Workplace: a Prognosis and Prescription for Institutional Health at the University of Guam Helen Thompson

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 13 May-2009 Designing a Woman-friendly Workplace: A Prognosis and Prescription for Institutional Health at the University of Guam Helen Thompson Andrea Sant Hartig Diane Thurber Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Helen; Hartig, Andrea Sant; and Thurber, Diane (2009). Designing a Woman-friendly Workplace: A Prognosis and Prescription for Institutional Health at the University of Guam. Journal of International Women's Studies, 10(4), 203-219. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol10/iss4/13 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2009 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Designing a Woman-friendly Workplace: A Prognosis and Prescription for Institutional Health at the University of Guam By Helen Thompson,1 Andrea Sant Hartig,2 & Diane Thurber3 Abstract This article explores the campus activist and research efforts made possible through a Campus Action Project grant awarded by AAUW (2006-2007) to the University of Guam (UOG). Faculty-student researchers developed a workshop series addressing women's workplace concerns and conducted research investigating the health of UOG through selected key indicators of a woman-friendly institution. This article focuses on the research findings, the impact of the grant efforts, and recommendations for institutional changes. -

Micronesian College Students in Hawaiʻi

SUCCESSFUL PRACTICES OF MICRONESIAN COLLEGE STUDENTS IN HAWAIʻI: UTILIZING POSITIVE DEVIANTS TO DEVELOP STRENGTH-BASED STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES IN HIGHER EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION IN PROFESSIONAL EDUCATIONAL PRACTICE AUGUST 2017 By Vidalino S. Raatior Dissertation Committee: Jeffrey A.S. Moniz, Chairperson Mary Therese Perez Hattori Denise L. Uehara Keywords: Micronesia. Positive Deviance, Strength-based student services DEDICATION Atʻtirow Tirow womi rewe Urupuwulo Kuor, father figure, promised brother, and role model of dignity, wisdom, generosity, love, and humility for me and my siblings. Ngenir fin me re Pwaraka me Alengeitaw, my ancestors whose DNA of strong women, brave warriors, humble chiefs, wise navigators, loving parents, and compassionate leaders I proudly carry in my blood. All shortcomings are entirely mine. Ngenir rhoe naai Tupuniol, Naihangiluk me Rahutow, my wife and children whose love have kept me going on this difficult doctoral journey and in life. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT Iʻm grateful for the pilooy (companions) on this journey without whom I would have been lost in the vast sea of academia. Tupuniol - To Desha, my companion for life and most trusted captain of the Staley-Raatior canoe, who continues to guide the family canoe with such strength, grace, compassion, and conscientiousness. Thank you for your love and encouragement, your belief in me, but especially for taking care of our family while I pursued my dream. Your love is my constant companion on lonely days when all I had were lofty ideas and a basket of frustrations. -

Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders Melody Dawn Ratliff The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ratliff, Melody Dawn, "Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4275. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4275 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUTATING MORPHOSCOPIC TRAIT FREQUENCIES OF SOUTHEAST ASIANS AND PACIFIC ISLANDERS By MELODY DAWN RATLIFF Bachelor of Arts, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 2012 Master’s Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Randall R. Skelton, Ph.D., Chair Department of Anthropology Ashley H. McKeown, Ph.D., Co-Chair Department of Anthropology Jeffrey M. Good, Ph.D., Co-Chair Division of Biological Sciences Joseph T. Hefner, Ph.D., D-ABFA Co-Chair JPAC-CIL, Hickam AFB, HI COPYRIGHT by Melody Dawn Ratliff 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Ratliff, Melody, M.A., May 2014 Anthropology Evaluating Morphoscopic Trait Frequencies of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders Chairperson: Randall Skelton, Ph.D.