Recognition of Black Issues by Non-Black Members of Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William F. Haddad Interviewer: Larry J

William F. Haddad Oral History Interview – RFK, 02/27/1969 Administrative Information Creator: William F. Haddad Interviewer: Larry J. Hackman Date of Interview: February 27, 1969 Place of Interview: New York, New York Length: 35 pages Biographical Note Haddad was the Associate Director, Inspector General of the Peace Corps, 1961-1963; Special Assistant to Robert F. Kennedy, 1960 Presidential Campaign; Campaign Advisor Robert F. Kennedy for President, 1968. In this interview, he discusses his work on the campaigns of multiple politicians, the organizing of Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign, and RFK’s strengths as a political leader, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed June 5, 2002, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Ford Newsletter April-May 1972

April 3, 1972 HOUSE PASSES FAR-REACHING WATER POLLUTION CONTROL BILL After three days of debate and consideration of numerous amendments, the House last week approved a momentous $24.6 billion three-year water pollution control bill with authority tor a crash program to clean up the Great Lakes. I strongly supported the bill. I resurrected the special Great Lakes cleanup program after the Office of Management and Budget had shot it down by l eaving it out of the fiscal 1973 budget. In a colloquy on the House floor with Rep. Bob Jones, D-Ala. , floor manager of the bill, Rep. William Harsha, R-Ohio, senior Republican on the House Public Works Committee, and Rep. John Blatnlk~ D-Minn .• Committee chairman, I established the fact that there is ample authority in existing law and in the House bill to proceed with the Great Lakes crash cleanup program. Earlier r met vi th officials of the Environmental Protection Agency, who assured me there would be sufficient funds under the overall $24.6 billion authorization in the bill to take care of the Great Lakes program. I now will york on the House Appropriations Committee to obtain funds for a Great Lakes cleanup. The main thrust of the Great Lakes program is a $100 million attack on the problem of com bined sanitary and storm vater sewage. EPA wants the storm vater as well as the sanitary sewage treated before it flows into the Great Lakes . I aim to see that the program is launched. WATER POLLUTION CONTROL BILL IS LANDMARK LEGISLATION As Congressman Harsha remarked , "Anyone who thinks the House water pol lution control bill is \leak simply doesn't know what's in it. -

<Iongrcssional Record

<iongrcssional Record. United States of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 92d CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-Monday, September 18, 1972 The House met at 12 o'clock noon. Senate had passed with amendments in agreeing votes of the two Houses thereon,. The Chaplain, Rev. Edward G. Latch, which the concurrence of the House is and appoints Mr. FULBRIGHT, Mr. SPARK D.D., offered the following prayer: requested bills and joint resolutions of MAN, Mr. CHURCH, Mr. SYMINGTON, Mr. I turn my face to the Lord God, seek the House of the following titles: AIKEN, Mr. CASE, and Mr. COOPER to be ing Him by prayer and supplications H .R. 10243. An act to establish an Office of the conferees on the part of the Senate. with fasting.-Daniel 9: 3. Technology Assessment for the Congress as The message also announced that the Eternal God, our rock of refuge in an aid in the identification .and consideration Senate disagrees to the amendment of of existing and probable impacts of techno the· House to the bill (S. 141) entitled every age and our strength for the pres logical appHcation; to amend the National ent hour, we come before Thee realizing "An act to establish the Fossil Butte Na Science Foundation Act of 1950; and for tional Monument in the State of Wy that we have mishandled the life Thou other purposes;- hast entrusted to us. We have done those H.R. 11948. An act to amend the joint res oming, and for other purposes," requests things we ought not to have done and olution authorizing appropriations for a conference with the House on the dis have left undone those things we ought p.articipation by the United States in the agreeing votes of the two Houses thereon, to have done. -

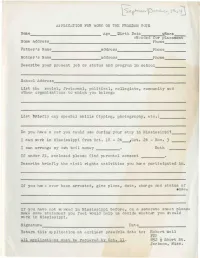

Describe Your Present Job Or Status and Program in School School

j ^-e-^^^Vrcv JO cH-«Jo-_- | <* c? *f 1 APPLICATION FOR WORK ON THE FREEDOM VOTE Name Age Dirth Date _Race vNeeded for placement Home Address Phone Father's Name Address Phone_ Mother's Name Address Phone_ Describe your present job or status and program in school School Address List the social, fraternal, political, collegiate, community aid other organizations to which you belong: List briefly any special skills (typing, photography, etc.)_ Do you have a car you could use during your stay in Mississippi?^ I can work in Mississippi from Oct. 18 - 26 ,Qct. 26 - Nov. 3 I can arrange my own bail money . Both _ If under 21, enclosed please find parental consent . Describe briefly the civil rights activities you ha/e participated in, If you have ever been arrested, give place, date, charge and status of •ase. If you have not TO rked in Mississippi before, on a separate sheet please make some statement you feel would help us decide whether you should work in Mississippi. Signature Date Return this qp plication at earliest possible date to: Robert Weil FDP All applications must be recieved by Oct. 11. 852 ^ Short St. Jackson, Miss. [ho-v^UrT, /96-<7] HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES CONGRESS OP THE UNITED STATES In the Matter of the NOTICE OF INTENTION TO CONTEST ELECTION Contested Election of JAMIE L. WHITTEN PURSUANT TO TITLE 2 in the 2nd Congressional District of U.S.C. Sec. 201 Mississippi. TO: JAMIE L. WHITTEN, Charleston, Mississippi: The undersigned hereby notifies you, pursuant to Title 2, U.S.C. -

Gateway Alai

basic information september 1975 1 , 5 :a GATEWAY ALAI 1 1 NATIONAL RECREATION AREA / NEW YORK-NEW JERSEY -1 690 /139 994 PURPOSE The purpose of Gateway National Recreation Area, as defined in its enabling legislation (Public Law 92-592, October 27,1972), is to "preserve and protect . for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations an area possessing outstanding natural and recreational features. ." DESCRIPTION Four management units have been designated at Gateway, which correspond to the geographically separated land areas that are joined by New York Bay (see Gateway map): The Jamhica Bay Unit, encompassing approximately 16,000 acres of drylands, marshlands, and waters in and adjacent to Jamaica Bay, includes the lands and facilities of the former naval air station at Floyd Bennett Field (the present park headquarters site), the existing parklands at Dead Horse Bay, Frank Charles Memorial Park, Plumb Beach, and Canarsie Beach Park, and the important Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. The Breezy Point Unit, south of Jamaica Bay on the western end of Rockaway Peninsula, contains about 1,600 acres and 4% miles of ocean beaches, including the popular Jacob Riis Park, the lands and facilities at Fort Tilden, and the shoreline abutting the Breezy Point Cooperative. The Staten Island Unit, extending along the eastern shore of Staten Island, includes Great Kills Park, Miller Field, and a portion of historic Fort Wadsworth, as well as two small manmade islands, Hoffman and Swinburne - a total of more than 2,900 acres. The Sandy Hook Unit contains nearly 4,600 acres along the largely undisturbed peninsula at the northern end of the New Jersey coast. -

Ronnie Eldridge Oral History Interview – RFK #1, 4/21/1970 Administrative Information

Ronnie Eldridge Oral History Interview – RFK #1, 4/21/1970 Administrative Information Creator: Ronnie Eldridge Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: April 21, 1970 Length: 98 pages Biographical Note Eldridge, New York City district leader for the Reform Independent Democrats (1963- 1968) and vice chairperson of Citizen’s Committee for Robert F. Kennedy (1968), discusses Robert F. Kennedy’s (RFK) 1964 New York senatorial campaign, the 1966 New York surrogate court’s race, and Frank O’Connor’s 1966 gubernatorial campaign, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 21, 1994, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

John J. Burns, Oral History Interview – RFK#1, 11/25/1969 Administrative Information

John J. Burns, Oral History Interview – RFK#1, 11/25/1969 Administrative Information Creator: John J. Burns Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: November 25, 1969 Location: New York, New York Length: 46 pages Biographical Note Burns was Mayor of Binghamton, NY (1958-1966); chairman of the New York State Democratic Party (1965-1973); delegate to the Democratic National Convention (1968); and a Robert Kennedy campaign worker (1968). In this interview, he discusses the Robert F. Kennedy’s (RFK) decision to run for president in 1968, and the presidential campaign in New York State; RFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and Johnson’s decision not to run for reelection in 1968; negotiations with the Eugene J. McCarthy campaign over electoral delegates, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials have passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Eighty-Seventh Congress January 3, 1961, to January 3, 1963

EIGHTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1961, TO JANUARY 3, 1963 FIRST SESSION-January 3, 1961, to September 27, 1961 SECOND SESSION-January 10, 1962,1 to October 13, 1962 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES-RICHARD M. NIXON,2 of California;LYNDON B. JOHNSON,2 of Texas PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE-CARL HAYDEN, of Arizona SECRETARY OF THE SENATE-FELTON MCLELLAN JOHNSTON, of Mississippi SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE-JOSEPH C. DUKE, of Arizona SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-SAM RAYBURN,4of Texas; JOHN W. MCCORMACK,5 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE-RALPH R. ROBERTS,6 of Indiana SERGEANT OF ARMS OF THE HOUSE-ZEAKE W. JOHNSON, JR.,6 ofTennessee DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE-WILLIAM M. MILLER,6 of Mississippi POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE-H. H. MORRIS,6 of Kentucky ALABAMA Barry M. Goldwater, Phoenix John E. Moss, Jr., Sacramento SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES William S. Mailliard, San Francisco Lister Hill, Montgomery John J. Rhodes, Mesa John F. Shelley, San Francisco John J. Sparkman, Huntsville Stewart L. Udall,' Tucson John F. Baldwin, Martinez Morris K. Udall,8 Tucson Jeffery Cohelan, Berkeley REPRESENTATIVES George P. Miller, Alameda Frank W. Boykin, Mobile ARKANSAS J. Arthur Younger, San Mateo George M. Grant, Troy Charles S. Gubser, Gilroy George W. Andrews, Union Springs SENATORS John J. McFall, Manteca Kenneth A. Roberts, Anniston John L. McClellan, Camden Bernice F. Sisk, Fresno Albert Rains, Gadeden J. William Fulbright, Fayetteville Charles M. Teague, Ojai Armistead I. Selden, Jr., Greensboro REPRESENTATIVES Harlan F. Hagen, Hanford Carl A. Elliott, Jasper Ezekiel C. Gathings, West Memphis Gordon L. -

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: Background and Recent

THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY Background lnformaUon for SUpportive Campaigns by Campus Groups repared by STEVE MAX Political Education ProJect, Room 309, 119 Firth Ave., N. Y .c. 10003 Associated with Students for a Democratic Society THE MISSISSIPPI FREEDOM DEMOCRATIC PARTY: BACKGROUND AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS by STEVE IvlAX The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was founded April 26, 1964 in order to create an opportunity for meaningful political expres sion for the 438,000 adult Negro Mississippians ~ho traditionally have been denied this right. In-addition to being a political instrument, the FDP provides a focus for the coordination of civil rights activity in the state and around the country. Although its memters do not necessarily· think in the se -terms, the MFDP is the organization above all others whose work is most directly forcing a realignment within the Democratic Party. All individuals and organizations who understand that ' when the Negro is not free, then all are in chains; who realize that the present system of discrimi nation precludes the abolition of poverty, and who have an interest in t he destruction of the Dixiecrat-Republican alliance and the purging of the racists from the Democratic Party are poteptial allies of the MFDP. BACKGROUND INFORMATION- The Mississippi Democratic Party runs the state of Mississippi _wit h an iron hand·. It controls the legislative, executive and judicial be nches of the state government. Prior to the November, 1964 elec tion all 49 state Senators and all but one of the 122 Representa tives were Democrats. Mississippi sent four Democrats and one Goldwater Republican to Congress last November. -

Eighty-Eighth Congress January 3, 1963, to January 3, 1965

EIGHTY-EIGHTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1963, TO JANUARY 3, 1965 FIRST SESSION—January 9, 1963, 1 to December 30, 1963 SECOND SESSION—January 7, 1964, 2 to October 3, 1964 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—LYNDON B. JOHNSON, 3 of Texas PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—CARL HAYDEN, of Arizona SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—FELTON MCLELLAN JOHNSTON, of Mississippi SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—JOSEPH C. DUKE, of Arizona SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JOHN W. MCCORMACK, 4 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—RALPH R. ROBERTS, 4 of Indiana SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—ZEAKE W. JOHNSON, JR., 4 of Tennessee DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM M. MILLER, 4 of Mississippi POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—H. H. MORRIS, 4 of Kentucky ALABAMA Barry M. Goldwater, Phoenix John E. Moss, Sacramento SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Robert L. Leggett, Vallejo John J. Rhodes, Mesa John F. Shelley, 10 San Francisco Lister Hill, Montgomery 11 John J. Sparkman, Huntsville Morris K. Udall, Tucson Phillip Burton, San Francisco George F. Senner, Jr., Miami William S. Mailliard, San REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Francisco George M. Grant, Troy ARKANSAS Jeffery Cohelan, Berkeley George Andrews, Union Springs George P. Miller, Alameda Kenneth A. Roberts, Anniston SENATORS John L. McClellan, Camden Don Edwards, San Jose Albert Rains, Gadsden Charles S. Gubser, Gilroy Armistead I. Selden, Jr., J. William Fulbright, Fayetteville J. Arthur Younger, San Mateo Greensboro REPRESENTATIVES Burt L. Talcott, Salinas Carl Elliott, Jasper E. C. Gathings, West Memphis Charles M. Teague, Ojai Robert E. Jones, Scottsboro Wilbur D. Mills, Kensett George Huddleston, Jr., John F. -

H. Doc. 108-222

EIGHTY-EIGHTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1963, TO JANUARY 3, 1965 FIRST SESSION—January 9, 1963, 1 to December 30, 1963 SECOND SESSION—January 7, 1964, 2 to October 3, 1964 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—LYNDON B. JOHNSON, 3 of Texas PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—CARL HAYDEN, of Arizona SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—FELTON MCLELLAN JOHNSTON, of Mississippi SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—JOSEPH C. DUKE, of Arizona SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—JOHN W. MCCORMACK, 4 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—RALPH R. ROBERTS, 4 of Indiana SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—ZEAKE W. JOHNSON, JR., 4 of Tennessee DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—WILLIAM M. MILLER, 4 of Mississippi POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—H. H. MORRIS, 4 of Kentucky ALABAMA Barry M. Goldwater, Phoenix John E. Moss, Sacramento SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES Robert L. Leggett, Vallejo John J. Rhodes, Mesa John F. Shelley, 10 San Francisco Lister Hill, Montgomery 11 John J. Sparkman, Huntsville Morris K. Udall, Tucson Phillip Burton, San Francisco George F. Senner, Jr., Miami William S. Mailliard, San REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Francisco George M. Grant, Troy ARKANSAS Jeffery Cohelan, Berkeley George Andrews, Union Springs George P. Miller, Alameda Kenneth A. Roberts, Anniston SENATORS John L. McClellan, Camden Don Edwards, San Jose Albert Rains, Gadsden Charles S. Gubser, Gilroy Armistead I. Selden, Jr., J. William Fulbright, Fayetteville J. Arthur Younger, San Mateo Greensboro REPRESENTATIVES Burt L. Talcott, Salinas Carl Elliott, Jasper E. C. Gathings, West Memphis Charles M. Teague, Ojai Robert E. Jones, Scottsboro Wilbur D. Mills, Kensett George Huddleston, Jr., John F. -

Linda Melconian Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript

Linda Melconian Assistant Counsel and Legislative Assistant, Speaker Thomas P. (Tip) O’Neill of Massachusetts Oral History Interview Final Edited Transcript June 7, 2018 Office of the Historian U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. “One time, we were talking to other female Members and maybe there were three or four of us— two staff people and one or two Members. Male Members would come over to us and say, ‘Oh, what are you girls cooking up? Are you conspiring against us?’ . Three or more women . on the floor congregating—chatting—would cause concern among the male Members. Were we conspiring against them? What I found so fascinating about this experience is that years later, when I served in the Massachusetts senate [during] my freshman year, I was talking to two other female members. I had male state senators come up to us and say, ‘Are you three conspiring against us?’ I thought, ‘I can’t believe this. It’s happening here in Massachusetts years later—the same thing that happened on the House Floor in Washington.’” Linda Melconian June 7, 2018 Table of Contents Interview Abstract i Interviewee Biography ii Editing Practices iii Citation Information iii Interviewer Biography iv Interview One 1 Notes 55 Abstract Linda Melconian was a recent college graduate when Congressman Thomas P. (Tip) O’Neill of Massachusetts hired her in 1971. During the next decade, she worked closely with O’Neill as he moved up the leadership ladder from Majority Whip, to Majority Leader, and, finally, to Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.