The Chicago Lakefront, Montgomery Ward, and the Public Dedication Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago's Evolving City Council Chicago City Council Report #9

Chicago’s Evolving City Council Chicago City Council Report #9 June 17, 2015 – March 29, 2017 Authored By: Dick Simpson Maureen Heffern Ponicki Allyson Nolde Thomas J. Gradel University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Political Science May 17, 2017 2 Since Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the new Chicago City Council were sworn in two years ago, there have been 67 divided roll call votes or roughly three per month. A divided roll call vote is not unanimous because at least one or more aldermen votes against the mayor and his administration. The rate of divided roll call votes – twice the rate in Emanuel’s first four year term – combined with an increase in the number of aldermen voting against the mayor – are indications that the aldermen are becoming more independent. Clearly, the city council is less of a predictable “rubber stamp” than it was during Mayor Richard M. Daley’s 22 years and Emanuel’s first four year term from 2011-2015. However, this movement away from an absolute rubber stamp is small and city council is only glacially evolving. The increase in aldermanic independence is confirmed by a downward trend in the vote agreement with the mayor, with only five aldermen voting with him 100% of the time and another 22 voting with him 90%. The number of aldermen voting with the mayor less than 90% of the time on divided votes has risen to 23 over the last two years. Aldermen are also more willing to produce their own legislation and proposed solutions to critical city problems than in the past rather than wait for, or to clear their proposals with, the 5th floor. -

From Rubber Stamp to a Divided City Council Chicago City Council Report #11 June 12, 2019 – April 24, 2020

From Rubber Stamp to a Divided City Council Chicago City Council Report #11 June 12, 2019 – April 24, 2020 Authored By: Dick Simpson Marco Rosaire Rossi Thomas J. Gradel University of Illinois at Chicago Department of Political Science April 28, 2020 The Chicago Municipal Elections of 2019 sent earthquake-like tremors through the Chicago political landscape. The biggest shock waves caused a major upset in the race for Mayor. Chicago voters rejected Toni Preckwinkle, President of the Cook County Board President and Chair of the Cook County Democratic Party. Instead they overwhelmingly elected former federal prosecutor Lori Lightfoot to be their new Mayor. Lightfoot is a black lesbian woman and was a partner in a major downtown law firm. While Lightfoot had been appointed head of the Police Board, she had never previously run for any political office. More startling was the fact that Lightfoot received 74 % of the vote and won all 50 Chicago's wards. In the same elections, Chicago voters shook up and rearranged the Chicago City Council. seven incumbent Aldermen lost their seats in either the initial or run-off elections. A total of 12 new council members were victorious and were sworn in on May 20, 2019 along with the new Mayor. The new aldermen included five Socialists, five women, three African Americans, five Latinos, two council members who identified as LGBT, and one conservative Democrat who formally identified as an Independent. Before, the victory parties and swearing-in ceremonies were completed, politically interested members of the general public, politicians, and the news media began speculating about how the relationship between the new Mayor and the new city council would play out. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

Beyond Right Field Fence

Homers by Ruth and Bodie Win for Yankees Ov^r Cardinals.Giants Defeat San Antonio Babe's Clout Clears House McGraw Shifts How to Start the Day Wrong By BRIGGS Ponteau Beats Beyond Right Field Fence Veteran Benton ArchieWalker FlMC MORMiM<$- Tnewe^s <Seo«se PaptagaS- Tm« TRA1M 13 LATE BUT A nic«s 3e5AT BY The MrNM- - . Louisiana Towii Declares Half To Second Nine WALK To J'Ll tAJAve To HIM-- t DOm'T WHAT O*" IT ? <S66 NNMI* Wimdoxju- - njovjl> for a in Honor of A NiCE B»i5K K*JOVAJ HIM VERY XA^eCX- 8l)T WHY JUMP ON TMtr RA.IL- In 3 Holiday Tne ROAoa - - CaMFORTABLE R|7>E To Rounds STaTiOm l'M rceuiHG FIWE Tmev'Re ooinG Bambino's First and TctxaJM --'. TVll-S IS a Visit, Capacity Croyd Gives No r ^est AS LIGHT 7hsir se-sr PlN(2"TRAlf>» Sees the INines in a Fast Contest Manager Explana AS A FeATHE« 135-Ponnd State Big League tion of Move That Ma^ Loses Chaaipion Be Result of "Zim" Decision to Negre By R. J. Kelly AlTaii Boxer in Bout at Garden LAKE CHARLES, La., March 16.-.The Yankees emerged triumphant. By Charles A. Taylor The Amateur Athletic from their first test of the training season against Union held » major league opposi- SAN ANTONIO, Tex., March 16..Th< boxing tournament at Madison tion by defeating Branch Rickey's Cardinala in an old-fashioned slugging Giants defeated tho San Antonio Bcar.< Garden last Square' contest night. At least it wa, here this afternoon by a score of 14 to 9. -

S" Qe Ay% ~ ~O&A Yo, 1O Q1 B5

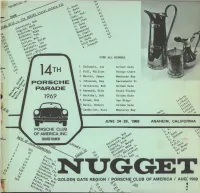

41 6 ~ @ete Ge Qe +~~ sts' seta ~o oe~ G' Octo Qe ~/Sf coot ~Qe ~ Cpa Oe ~aa ~ +eea sob y 0 Oe St ~eai Ge CP goe ~ea s" Qe ay% ~ ~o&a yO, 1O Q1 b5 yO Reitmeir, Joe Golden Gate ~4$ TH 2 Roll, William Grange Coas t 3 Masinl& James Monterey Bay 4 PORSCHE 4 Johansen, Ray Sacramento Vz 5 Garretson, Bob Golden Gate PARADE 6 Raymond, Dick Great Plains , ~ epee Wo~ 1969 Buckthal, Bob Golden Gate 8 Brown, Bob San Diego 9 Daves, Robert Golden Gate Sandholdt~ Pete Monterey Bay w~ 1o~ on JUMf 24-28, 1969 ANANf IIN, CALIFORNA PORSCHE eve v OF AMERICA We. ~o ~e 555K MNR 0 9 Oa oo eS g', 0 op yQ ae3 6J Oe p~ eel~ ie~ dO 6d ldG ~e e„, Jest, 'J. @~o GOLDEN GATE RE/ION / PORSCHE ClUS OF:AMERICA / Ale 0- -i This Noath~s nesting features the Rouse Specialty dinner «t KONNA ~ The barbequod Now Torh strip steak is fsnous for at least a nile md a half in all directions~ snd the Nsklava, that waits in your nouch, hem authentic Creek dessert Creat Chat you wiH especially reaeaher. After the dinner «esting you will wsnt Co stay for the late show in the lounge with dancing snd music haportsd d~y froms Athena, Ie en reservations (wo have roon for at least RSC), but dsn~t be late getting ~yours in; this dinner you wcn't want Co miss. N~EU XORNA Specialty Ssla4 New York Steah RSSO sa ssmccw AVDNK ~ SAM JOSE Sarboqued Strip Pheea: 20$-HBk Bshed potato «ith Sour Croaa Vegetable proach Nroad Nahlava ~Ok: Saturday Fling, August 9 QIBRMR: 'y:00 p n. -

The Chicago City Manual, and Verified by John W

CHICAGO cnT MANUAL 1913 CHICAGO BUREAU OF STATISTICS AND MUNICIPAL UBRARY ! [HJ—MUXt mfHi»rHB^' iimiwmimiimmimaamHmiiamatmasaaaa THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY I is re- The person charging this material or before the sponsible for its return on Latest Date stamped below. underlining of books Theft, mutilation, and disciplinary action and may are reasons for from the University. result in dismissal University of Illinois Library L161-O-1096 OFFICIAL CITY HALL DIRECTORY Location of the Several City Departments, Bureaus and Offices in the New City Hall FIRST FLOOR The Water Department The Fire Department Superintendent, Bureau of Water The Fire Marshal Assessor, Bureau of Water Hearing Room, Board of Local Improve^ Meter Division, Bureau of Water ments Shut-Off Division, Bureau of Water Chief Clerk, Bureau of Water Department of the City Clerk Office of the City Clerk Office of the Cashier of Department Cashier, Bureau of Water Office of the Chief Clerk to the City Clerk Water Inspector, Bureau of Water Department of the City Collector Permits, Bureau of Water Office of the City Collector Plats, Bureau of Water Office of the Deputy City Collector The Chief Clerk, Assistants and Clerical Force The Saloon Licensing Division SECOND FLOOR The Legislative Department The Board's Law Department The City Council Chamber Board Members' Assembly Room The City Council Committee Rooms The Rotunda Department of the City Treasurer Office of the City Treasurer The Chief Clerk and Assistants The Assistant City Treasurer The Cashier and Pay Roll Clerks -

CHICAGO: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress

CHICAGO: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress A Guide and Resources to Build Chicago Progress into the 8th Grade Curriculum With Literacy and Critical Thinking Skills November 2009 Presenting sponsor for education Sponsor for eighth grade pilot program BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS “Our children must never lose their zeal for building a better world. They must not be discouraged from aspiring toward greatness, for they are to be the leaders of tomorrow.” Mary McLeod Bethune “Our children shall be taught that they are the coming responsible heads of their various communities.” Wacker Manual, 1911 Chicago, City of Possibilities, Plans, and Progress 2 More Resources: http://teacher.depaul.edu/ and http://burnhamplan100.uchicago.edu/ BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS Table of Contents Teacher Preview …………………………………………………………….4 Unit Plan …………………………………………………………………11 Part 1: Chicago, A History of Choices and Changes ……………………………13 Part 2: Your Community Today………………………………………………….37 Part 3: Plan for Community Progress…………………………………………….53 Part 4: The City Today……………………………………………………………69 Part 5: Bold Plans. Big Dreams. …………………………………………………79 Chicago, City of Possibilities, Plans, and Progress 3 More Resources: http://teacher.depaul.edu/ and http://burnhamplan100.uchicago.edu/ BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS Note to Teachers A century ago, the bold vision of Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s The Plan of Chicago transformed 1909’s industrial city into the attractive global metropolis of today. The 100th anniversary of this plan gives us all an opportunity to examine both our city’s history and its future. The Centennial seeks to inspire current civic leaders to take full advantage of this moment in time to draw insights from Burnham’s comprehensive and forward-looking plan. -

Masters Thesis

WHERE IS THE PUBLIC IN PUBLIC ART? A CASE STUDY OF MILLENNIUM PARK A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corrinn Conard, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Masters Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. James Sanders III, Advisor Advisor Professor Malcolm Cochran Graduate Program in Art Education ABSTRACT For centuries, public art has been a popular tool used to celebrate heroes, commemorate historical events, decorate public spaces, inspire citizens, and attract tourists. Public art has been created by the most renowned artists and commissioned by powerful political leaders. But, where is the public in public art? What is the role of that group believed to be the primary client of such public endeavors? How much power does the public have? Should they have? Do they want? In this thesis, I address these and other related questions through a case study of Millennium Park in Chicago. In contrast to other studies on this topic, this thesis focuses on the perspectives and opinions of the public; a group which I have found to be scarcely represented in the literature about public participation in public art. To reveal public opinion, I have conducted a total of 165 surveys at Millennium Park with both Chicago residents and tourists. I have also collected the voices of Chicagoans as I found them in Chicago’s major media source, The Chicago Tribune . The collection of data from my research reveal a glimpse of the Chicago public’s opinion on public art, its value to them, and their rights and roles in the creation of such endeavors. -

LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014

THE LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014 Mayor Rahm Emanuel City Hall - 121 N LaSalle St. Chicago, IL 60602 Dear Mayor Emanuel, As co-chairs of the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Site Selection Task Force, we are delighted to provide you with our report and recommendation for a site for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. The response from Chicagoans to this opportunity has been tremendous. After considering more than 50 sites, discussing comments from our public forum and website, reviewing input from more than 300 students, and examining data from myriad sources, we are thrilled to recommend a site we believe not only meets the criteria you set out but also goes beyond to position the Museum as a new jewel in Chicago’s crown of iconic sites. Our recommendation offers to transform existing parking lots into a place where students, families, residents, and visitors from around our region and across the globe can learn together, enjoy nature, and be inspired. Speaking for all Task Force members, we were both honored to be asked to serve on this Task Force and a bit awed by your charge to us. The vision set forth by George Lucas is bold, and the stakes for Chicago are equally high. Chicago has a unique combination of attributes that sets it apart from other cities—a history of cultural vitality and groundbreaking arts, a tradition of achieving goals that once seemed impossible, a legacy of coming together around grand opportunities, and not least of all, a setting unrivaled in its natural and man-made beauty. -

Chicago No 16

CLASSICIST chicago No 16 CLASSICIST NO 16 chicago Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 20 West 44th Street, Suite 310, New York, NY 10036 4 Telephone: (212) 730-9646 Facsimile: (212) 730-9649 Foreword www.classicist.org THOMAS H. BEEBY 6 Russell Windham, Chairman Letter from the Editors Peter Lyden, President STUART COHEN AND JULIE HACKER Classicist Committee of the ICAA Board of Directors: Anne Kriken Mann and Gary Brewer, Co-Chairs; ESSAYS Michael Mesko, David Rau, David Rinehart, William Rutledge, Suzanne Santry 8 Charles Atwood, Daniel Burnham, and the Chicago World’s Fair Guest Editors: Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker ANN LORENZ VAN ZANTEN Managing Editor: Stephanie Salomon 16 Design: Suzanne Ketchoyian The “Beaux-Arts Boys” of Chicago: An Architectural Genealogy, 1890–1930 J E A N N E SY LV EST ER ©2019 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 26 All rights reserved. Teaching Classicism in Chicago, 1890–1930 ISBN: 978-1-7330309-0-8 ROLF ACHILLES ISSN: 1077-2922 34 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Frank Lloyd Wright and Beaux-Arts Design The ICAA, the Classicist Committee, and the Guest Editors would like to thank James Caulfield for his extraordinary and exceedingly DAVID VAN ZANTEN generous contribution to Classicist No. 16, including photography for the front and back covers and numerous photographs located throughout 43 this issue. We are grateful to all the essay writers, and thank in particular David Van Zanten. Mr. Van Zanten both contributed his own essay Frank Lloyd Wright and the Classical Plan and made available a manuscript on Charles Atwood on which his late wife was working at the time of her death, allowing it to be excerpted STUART COHEN and edited for this issue of the Classicist. -

Calendar Highlights-October FINAL.01-20-10

October 2009 Calendar of Exhibits and Events Visit burnhamplan100.org to learn about the plans of more than 250 program partners offering hundreds of ways for the people of Chicago's three-state metropolitan region to dream big and plan boldly. October Events: Public Programs, Tours, Lectures, Performances, Symposia John Marshall Law School Law As Hidden Architecture October 1 Chicago Public Library, Sulzer Make No Little Plans: Daniel Burnham and the Regional Library American City Documentary Film October 1 A Portrait of Daniel Burnham: Historical Chicago Ridge Public Library Reenactment October 1 Chicago Architecture Foundation White City Revisited Tour October 3 Burnham and Bennett from the Boat: River Chicago Architecture Foundation Cruise with Geoffrey Baer October 3 Niles Public Library District The Life and Contributions of Billy Caldwell October 4 Museum of Science and Industry Blueprints to Our Past Tour October 4 Daniel Burnham's Chicago: Historical Evanston Public Library Reenactment October 4 Chicago Architecture Foundation Daniel Burnham: Architect, Planner, Leader Tour October 4 & 16 Lewis University The Imprint of the World Columbian Exposition October 5 Chicago Public Library, Harold One Book, One Chicago: The Unraveling of Washington Library Chicago Public Housing October 6 Chicago Public Library, Woodson Make No Little Plans: Daniel Burnham and the Regional Library American City Documentary Film October 7 A Portrait of Daniel Burnham: Historical Indian Prairie Public Library Reenactment October 7 Chicago as the Nation's