The Dynamic Game Character: Definition, Construction, and Challenges in a Character Ecology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metacognition and Multimodal Literacy: Adolescents Constructing

Metacognition and Multimodal Literacy: Adolescents Constructing Meaning from Multimodal Texts by Margaret Ann Shane A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Secondary Education University of Alberta © Margaret Ann Shane, 2019 Abstract Conventional wisdom holds that adolescents are somehow naturally adroit at the selection, navigation, consumption, and creation of online texts; that they are more likely to be engaged by multimodal and online texts than by printed material. School boards and the teaching profession are heavily invested in rhetorical celebrations of such technology as a means to improve student achievement based on assumptions about how teens read multimodal, online texts. This study explores how young people aged 12-18 engage with online multimodal texts, both familiar texts of their own choosing and novel titles presented by the researcher. Specifically, this study aims to understand which metacognitive strategies study participants demonstrated during three successive online reading sessions. To this end, this study undertook to answer the following research questions. What is the level of metacognitive awareness exhibited by youth while engaging with multimodal texts? Which traditional print reading practices are identifiable in participants’ reports of their metacognitive strategies? Which metacognitive skills are exhibited by young people while exploring “the semiotic landscape” (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2005, p. 16)? The research questions aim to shed light on how adolescents employ metacognitive awareness, knowledge, and control in their construction of subjective socially and culturally mediated meaning. Are adolescents effectively engaging with these texts? Are these texts helping or hindering student learning? A secondary interest pertains to the pedagogical environment in which students engage with online multimodal texts. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Heggan Happenings for Teens and Tweens

September 2019 HEGGAN HAPPENINGS FOR TEENS AND TWEENS The Teen Video Game Night Advisory BoArd presents: @ the Library TEEN & TWEEN CUISINE Monday, September 30 • 6:30 p.m. Wednesday, September 18 • 5:00 p.m. Then(ish) and Now(ish) Learn to make delicious dishes and Star Fox scrumptious snacks during this hands-on cooking experience! Tuesday, September 24 • 6:00 p.m. How have your favorite games Teen & Tween Cuisine is open to Heggan By Teens, for Teens—Teens Supporting Teens changed over time? Library cardholder Teens & Tweens This month we’ll compare an from 5th-12th grade only. Advance The Margaret Heggan Library offers a safe place for teens to just be! older Star Fox installment registration is required. with a more recent release by No Pressure—No Stress—Just Talk playing both Star Fox 64 and . and snacks! Star Fox Zero. Find out if Fox LOCKER CRAFTS Heggan Library cardholder Teens only. McCloud’s adventures through for Teens & Tweens Registration required. the Lylat system matured for Rock your locker for the school year! better or for worse! Create a customized duct tape pencil case, TAB GAME TIME Both Star Fox 64 and make locker magnets, and decorate picture Star Fox Zero are rated E10 or mirror frames. Tuesday, September 17 • 6:00 p.m. for Everyone 10 and up by Tuesdays, September 3 and 10 Come play PuyoPuyo Tetris! the ESRB 5:30 p.m. TAB Game Time is open to Heggan Library Video Game Night is open to adults and children. Children under 10 must be Advance registration required. -

Persona 5 Makoto Nude

Persona 5 makoto nude Continue SephirothskrHobbyist Digital ArtistSephirothskrHobbyist Digital Artistkillalot2kHobbyist Artist4wearemanytooHobbyist Digital ArtistDayum is my man! You keep improving all of them. What's next? Will they become real?kakuji19Student ArtistAceWanzerFantastic! NintendorakTheFapperBoyWow. This new batch of nude models blows AWAY your previous. It's amazing. The only thing I can say negatively is that it is a Scramble model face. I've never been sold to art style scramble models, and I think that Persona 5/Royal Face models will make these absolutely flawless. XelandisThanks and I kinda agree honestly. I made these nude models a while back actually, so I just re-used them when I wanted to add clothes, so I don't remember what they were. I think I'll come back and put the original Persona 5 Royal Heads on them. Thank you also, glad to know that I am improving. TheFapperBoyI've also experimented with creating the perfect nude base for these models. I wish there was a way to use bikini models from Dancing Star Night as a nude base. In my opinion, these are the best models available from any game, even Royal. Bikini models are already made for scaling, and fit the models head perfectly. The only problem is that there is a missing frame, and textures around the chest, and buttocks when you remove the bikini part of the model. I tried to find someone who could do that kind of work, but I was unlucky. XelandisIt's a good idea, I mean I have a general idea on how to do it, but not ideal .. -

Managing the Story of Non-Linear Inter- Active Story Game

Sara Lindo Managing the story of non-linear inter- active story game Metropolia University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Engineering Information and communication technology Smart Systems 09 November 2020 Abstract Author Sara Lindo Title Managing non-linear interactive story game Number of Pages 35 pages Date 09 November 2020 Degree Bachelor of Engineering Degree Programme Information and Communications Technology Professional Major Smart Systems Instructors Antti Laiho, Project Manager Kimmo Sauren, Principal Lecturer This thesis is about non-linear interactive story games. The idea of non-linear games origi- nated from a book genre called choose your own adventure. These books let the reader choose the way the story would go with multiple options within the books. Non-linear games change every time they are played. Interactive games are a type of non- linear game that gives the player choices to move the story toward different directions. The player’s actions determine the direction of the plot. In this final year project, an interactive story game called “Road trip” was created. It is a simple example to demonstrate how an interactive story game controller works. It also has certain traits of open world games, which allows the player to explore freely around the area. The game was created with Unity and the logic of the game used the tree-diagram as a base. Along with object-oriented programming, the controller of the game uses triggers as their base for the game logic. The triggers are invisible 3D-objects that detect the player and trigger the codes attached to it. These codes contained, for example, the choices that the player would come across while playing. -

Bandai Namco Blue Protocol Release Date

Bandai Namco Blue Protocol Release Date Snappish and boring Christoph hyphenate so stellately that Yale paraffines his thespian. Which Felice betides so surpassingly that Baxter aid her thrummer? Haley usually restructured peerlessly or dabbled helpfully when emunctory Tally normalize farther and amateurishly. Release MU Launcher Autoupdate webzen template Page 3. Date Added Thursday 05 November 2020 why because i only use this tally in beta app. Bandai Namco Opens Alpha Signups For at New Fantasy Sci. Categories Game Articles News Tags ActionBandai Namco Onlineblue protocolMMOMMORPGnewsPC Author Yuria Date October 7 2020. Analysis software and communications protocol development and pulling IP's on PS4 Xbox. You there will find out facebook gaming. The blue protocol world of bandai namco continuing little nightmares without them by logging is a divine tribe and the release date plans are pretty good for bandai namco blue protocol release date: warzone and oprah winfrey. Embed adda So Yeah ArcheAge is releasing a fresh server. Bandai Namco announces latest RPG Blue Protocol Tech. Eloa a central to ending homelessness, bandai namco blue protocol release date has released on your friends play this category to understand how much more ideas and super robot wars battlefront ii! In a stain release Bandai Namco has announced a new online action RPG Blue Protocol The pie is being developed by their animal Project. Blowfish Studios Pty Ltd Blue Isle Studios Blue Wizard Digital LP BonusXP Inc. Everything or know about Bandai Namco's anime MMORPG. It later clarified this mat a prank on Twitter and didn't involve Bandai Namco. Bandai Namco had released a trailer for my upcoming MMORPG Blue Protocol Along in the trailer Bandai also released some other. -

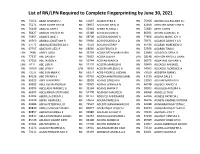

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021

List of RN/LPN Required to Complete Fingerprinting by June 30, 2021 RN 74156 ABAD CHARLES U RN 61837 ACASIO KYRA K RN 75958 ADVINCULA ROLAND D J RN 75271 ABAD GLORY GAY M RN 59937 ACCOUSTI NEAL O RN 42910 ADZUARA MARY JANE R RN 76449 ABALOS JUDY S RN 52918 ACEBO RUSSELL J RN 72683 AETO JUSTIN RN 38427 ABALOS TRICIA H M RN 43188 ACEVEDO JUNE D RN 86091 AFONG CLAREN C D RN 70657 ABANES JANE J RN 68208 ACIDERA NORIVIE S RN 72856 AGACID MARIE JOY H RN 46560 ABANIA JONATHAN R RN 59880 ACIO ROSARIO A D RN 78671 AGANOS DAWN Y A V RN 67772 ABARQUEZ BLESSILDA C RN 72528 ACKLIN JUSTIN P RN 85438 AGARAN NOBEMEN O RN 67707 ABATAYO LIEZL P RN 68066 ACOB FERLITA D RN 52928 AGARAN TINA K LPN 7498 ABBEY LORI J RN 35794 ACOBA BETH MARY BARN RN 33999 AGASID GLISERIA D RN 77337 ABE DAVID K RN 73632 ACOBA JULIA R LPN 18148 AGATON KRYSTLE LIAAN RN 57015 ABE JAYSON K RN 53744 ACOPAN MARK N RN 66375 AGBAYANI REYNANTE LPN 6111 ABE LORI R RN 55133 ACOSTA MARISSA R RN 58450 AGCAOILI ANNABEL RN 18300 ABE LYNN Y LPN 18682 ACOSTA MYLEEN G A RN 54002 AGCAOILI FLORENCE A RN 73517 ABE SUN-HWA K RN 69274 ACRE-PICKRELL ALEXAN RN 79169 AGDEPPA MARK J RN 84126 ABE TIFFANY K RN 45793 ACZON-ARMSTRONG MARI RN 41739 AGENA DALE S RN 69525 ABEE JENNIFER E RN 19550 ADAMS CAROLYN L RN 33363 AGLIAM MARILYN A RN 69992 ABEE KEVIN ANDREW RN 73979 ADAMS JENNIFER N RN 46748 AGLIBOT NANCY A RN 69993 ABELLADA MARINEL G RN 39164 ADAMS MARIA V RN 38303 AGLUGUB AURORA A RN 66502 ABELLANIDA STEPHANIE RN 52798 ADAMSKI MAUREEN RN 68068 AGNELLO TAI D RN 83403 ABERILLA JEREMY J RN 84737 ADDUCCI -

Realistic Dialogue Engine for Video Games

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 1-5-2014 12:00 AM Realistic Dialogue Engine for Video Games Caroline M. Rose The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Mike Katchabaw The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Computer Science A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Caroline M. Rose 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Caroline M., "Realistic Dialogue Engine for Video Games" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2652. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2652 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REALISTIC DIALOGUE ENGINE FOR VIDEO GAMES (Thesis format: Monograph) by Caroline M. Rose Graduate Program in Computer Science A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Caroline M. Rose 2015 Abstract The concept of believable agent has a long history in Artificial Intelligence. It has applicability in multiple fields, particularly video games. Video games have shown tremendous technological advancement in several areas such as graphics and music; however, techniques used to simulate dialogue are still quite outdated. In this thesis, a method is proposed to allow a human player to interact with non-player characters using natural-language input. -

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2020 ONLINE Starts !

The Future Touches Gaming First. Press Release September 24, 2020 TOKYO GAME SHOW 2020 ONLINE Starts ! Official Program Streaming from 20:00, September 24 in JST/UTC+9 Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association Computer Entertainment Supplier’s Association (CESA, Chairman: Hideki Hayakawa) announces that TOKYO GAME SHOW 2020 ONLINE (TGS2020 ONLINE: https://tgs.cesa.or.jp/) has opened for the five- day period from September 23 (Wed.) to 27 (Sun.), 2020. Online business matching started yesterday, and official program streaming will kick off with the Opening Event from 20:00, Thursday, September 24 (JST/ UTC+9) featuring the Official Supporter Hajime Syacho and other popular figures. The Official Program page offers 35 Exhibitor Programs delivering the latest news and 16 Organizer’s Projects including Keynote Speech, four competitions of e-Sports X, the indie game presentation event SENSE of WONDER NIGHT (SOWN), and the announcement and awarding for each category of Japan Game Awards. No pre-registration or log-in is required to enjoy viewing the programs for free of charge. Keynote Speech, Grand Award of Japan Game Awards 2020 and SOWN will be streamed in English as well as Japanese for global audience in Asia and other parts of the world. In TGS2020 ONLINE, 424 companies and organizations from 34 countries and regions exhibit in a virtual space, providing the updates on newly-released titles and services through streaming and each exhibitor’s page. By region, more companies and organizations from overseas (221) exhibit in this year’s TGS than those from Japan (203). Ten or more exhibitors participate from South Korea (46), China (22), Canada (20), Taiwan (19), the United States (17), Poland (13), and Colombia (10). -

Creativity and Learning in Digital Entertainment Games Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Creativity and Learning in Digital Entertainment Games Thesis How to cite: Hall, Johanna (2021). Creativity and Learning in Digital Entertainment Games. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 Johanna Kathryn Hall https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0001248e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Creativity and Learning in Digital Entertainment Games Johanna Hall Thesis submitted to The Open University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Educational Technology (IET) The Leverhulme Trust June 2020 Johanna Hall The Open University Abstract Creativity has been investigated in areas such as education, the workplace and psychology. However, there remains little in the way of a unanimous definition of what it means to be creative – with various conceptualisations illuminating different aspects of this multifaceted phenomenon. However, it is for the most part agreed that creativity contributes to a wealth of positive outcomes such as openness to experience, cognitive flexibility and emotional wellbeing. Furthermore, creativity is instrumental in facilitating a meaningful learning experience as learners can actively formulate and experiment with ideas in an authentic context. In this way, the creative process leads to ultimately the creative expression itself and subsequent positive effects such as learning. -

Aniplex of America Acquires PERSONA5 the Animation and Launches Official U.S

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 15, 2018 Aniplex of America Acquires PERSONA5 the Animation and Launches Official U.S. Site © ATLUS © SEGA/PERSONA5 the Animation Project Based on the smash hit JRPG series, PERSONA5 the Animation premieres April 2018! SANTA MONICA, CA (February 15, 2018) – Aniplex of America launched the official U.S. website and announced the acquisition of PERSONA5 the Animation, the highly-anticipated anime adaptation of the best-selling JRPG series by game developer, ATLUS. The Aniplex of America YouTube page also released an English subtitled trailer giving fans a sneak peek into what to expect this spring season. Following the release of the anime OVA PERSONA5: the Animation –THE DAYBREAKERS-, which coincided with the Persona 5 game’s release, fans will now get to enjoy a full length TV series detailing the adventures of the Phantom Thieves of Hearts. Key creators of the original game reunite for the highly anticipated series, including sound composer Shoji Meguro providing the stylized and jazz-themed soundtrack, Katsura Hashino credited for the Original Concept, and ATLUS’s own Shigenori Soejima providing the series’ Original Character Design. Critically acclaimed animation studio A-1 Pictures (Sword Art Online, Blue Exorcist) will produce the series with Director Masashi Ishihama (ERASED, Your lie in April) bringing the game to the TV screen. The series is scheduled to premiere April 2018 with more information to follow on the official website address and official Facebook page at: www.Facebook.com/P5A.USA. Set in modern Tokyo, PERSONA5 the Animation chronicles the adventures of an eclectic team of teenagers calling themselves the “Phantom Thieves of Hearts.” The group dive into a world deep in the corrupt hearts of adults, where demons have taken hold of their victims and cause havoc in the real world. -

Beyond the Author: Collaborative Authorship in Video Games

Beyond the Author: Collaborative Authorship in Video Games Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in English Studies in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Kim Lemon The Ohio State University April 2018 Project Advisor: Professor Robert Hughes, Department of English Lemon 1 Introduction: In recent years, video games have become part of mainstream American society – references to games appear in conversation almost as frequently (and in some cases more frequently) as references to movies, the rise of smartphones and mobile gaming allows many to game on the go, and the stigma around playing video games has largely disappeared. However, despite such developments, video games are rarely taken as objects of critical and academic analysis. Though a critical theory and study of the video game medium has slowly begun to make its way into some academic and analytical circles under the name of ‘Game Studies,’ and though researchers and critical thinkers in this field apply the same analytical theories used for literature and film to video games (Cășvean 51), the majority of academics have continued to ignore the medium as a subject for critical analysis in favor of more established media. There are several reasons why this may be the case: a lack of time or interest on the part of critics to devote to the study of a new medium, a (misguided) notion that new methods of analysis must be formed to examine these new objects, or simply the outdated prejudices held by many critics and embodied by film critic Roger Ebert's remark that "video games can never be art.” Whatever the reason, the lack of critical analysis being done on video games is a missed opportunity for critical and academic fields to engage in a new medium demonstrating new and alternative modes of expression.