Conversations with the Dead: Crisis in the Humanities and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking the Pulse of the Class of 1971 at Our 45Th Reunion Forty-Fifth. A

Taking the pulse of the Class of 1971 at our 45th Reunion Forty-fifth. A propitious number, or so says Affinity Numerology, a website devoted to the mystical meaning and symbolism of numbers. Here’s what it says about 45: 45 contains reliability, patience, focus on building a foundation for the future, and wit. 45 is worldly and sophisticated. It has a philanthropic focus on humankind. It is generous and benevolent and has a deep concern for humanity. Along that line, 45 supports charities dedicated to the benefit of humankind. As we march past Nassau Hall for the 45th time in the parade of alumni, and inch toward our 50th, we can at least hope that we live up to some of these extravagant attributes. (Of course, Affinity Numerology doesn’t attract customers by telling them what losers they are. Sixty-seven, the year we began college and the age most of us turn this year, is equally propitious: Highly focused on creating or maintaining a secure foundation for the family. It's conscientious, pragmatic, and idealistic.) But we don’t have to rely on shamans to tell us who we are. Roughly 200 responded to the long, whimsical survey that Art Lowenstein and Chris Connell (with much help from Alan Usas) prepared for our virtual Reunions Yearbook. Here’s an interpretive look at the results. Most questions were multiple-choice, but some left room for greater expression, albeit anonymously. First the percentages. Wedded Bliss Two-thirds of us went to the altar just once and five percent never married. -

Ideological Tension in Four Novels by Saul Bellow

Ideological Tension in Four Novels by Saul Bellow June Jocelyn Sacks Dissertation submitted in fulfilmentTown of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts atCape the Universityof of Cape Town Univesity Department of English April 1987 Supervisor: Dr Ian Glenn The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Contents Page. Abstract i Acknowledgements vi Introduction Chapter One Dangling Man 15 Chapter Two The Victim 56 Chapter Three Herzog 99 Chapter Four Mr Sammler's Planet 153 Notes 190 Bibliography 212 Abstract This study examines and evaluates critically four novels by Saul Bellow: Dangling Man, The Victim, Herzog and Mr Sammler's Planet. The emphasis is on the tension between certain aspects of modernity to which many of the characters are attracted, and the latent Jewishness of their creator. Bellow's Jewish heritage suggests alternate ways of being to those advocated by the enlightened thought of liberal Humanism, for example, or by one of its offshoots, Existenti'alism, or by "wasteland" ideologies. Bellow propounds certain ideas about the purpose of the novel in various articles, and these are discussed briefly in the introduction. His dismissal of the prophets of doom, those thinkers and writers who are pessimistic about the fate of humankind and the continued existence of the novel, is emphatic and certain. -

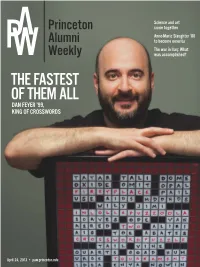

The Fastest of Them

00paw0424_coverfinalNOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 4/11/13 10:16 AM Page 1 Science and art Princeton come together Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 Alumni to become emerita The war in Iraq: What Weekly was accomplished? THE FASTEST OF THEM ALL DAN FEYER ’99, KING OF CROSSWORDS April 24, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu PAW_1746_AD_dc_v1.4.qxp:Layout 1 4/2/13 8:07 AM Page 1 Welcome to 1746 Welcome to a long tradition of visionary Now, the 1746 Society carries that people who have made Princeton one of the promise forward to 2013 and beyond with top universities in the world. planned gifts, supporting the University’s In 1746, Princeton’s founders saw the future through trusts, bequests, and other bright promise of a college in New Jersey. long-range generosity. We welcome our newest 1746 Society members.And we invite you to join us. Christopher K. Ahearn Marie Horwich S64 Richard R. Plumridge ’67 Stephen E. Smaha ’73 Layman E. Allen ’51 William E. Horwich ’64 Peter Randall ’44 William W. Stowe ’68 Charles E. Aubrey ’60 Mrs. H. Alden Johnson Jr. W53 Emily B. Rapp ’84 Sara E. Turner ’94 John E. Bartlett ’03 Anne Whitfield Kenny Martyn R. Redgrave ’74 John W. van Dyke ’65 Brooke M. Barton ’75 Mrs. C. Frank Kireker Jr. W39 Benjamin E. Rice *11 Yung Wong ’61 David J. Bennett *82 Charles W. Lockyer Jr. *71 Allen D. Rushton ’51 James K. H. Young ’50 James M. Brachman ’55 John T. Maltsberger ’55 Francis D. Ruyak ’73 Anonymous (1) Bruce E. Burnham ’60 Andree M. Marks Jay M. -

By 2007 a Dissertation Presented in Fulfilment of the Requirements of The

THE PROVOCATION OF SAUL BELLOW: PERFECTIONISM AND TRAVEL IN THE ADVENTURES OF AUGIE MARCH AND HERZOG by ADAM ATKINSON 2007 A dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in English University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy School of Humanities and Social Sciences ii * I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgment is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. ____________________________________ Adam Atkinson 30 June 2007 iii iv Abstract A consistent feature of Saul Bellow’s fiction is the protagonist’s encounter with one or more teaching figures. Dialogue with such individuals prompts the Bellovian protagonist to reject his current state of selfhood as inadequate and provokes him to re-form as a new person. The teacher figure offers a better self to which the protagonist is attracted; or, more frequently in Bellow, the protagonist is repelled by both his teacher and his own current state to form a new, previously unrepresented self. -

Download Ravelstein Penguin Great Books of the 20Th Century Pdf Book by Saul Bellow

Download Ravelstein Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century pdf book by Saul Bellow You're readind a review Ravelstein Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century ebook. To get able to download Ravelstein Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this ebook on an database site. Ebook Details: Original title: Ravelstein (Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century) Series: Penguin Great Books of the 20th Century 233 pages Publisher: Penguin Books; Reissue edition (May 1, 2001) Language: English ISBN-10: 9780141001760 ISBN-13: 978-0141001760 ASIN: 0141001763 Product Dimensions:5.1 x 0.6 x 7.8 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 6359 kB Description: Abe Ravelstein is a brilliant professor at a prominent midwestern university and a man who glories in training the movers and shakers of the political world. He has lived grandly and ferociously-and much beyond his means. His close friend Chick has suggested that he put forth a book of his convictions about the ideas which sustain humankind, or kill... Review: This is not a novel in any conventional sense of the word. It is something else. Yes, there is a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end; and something in the way of a structure--one, however, that more often than not resembles an old-fashioned rambling memoir, or even a long scholarly philosophical essay in a learned academic journal.Bellow is.. -

Moonglow by Michael Chabon

Moonglow: A Novel by Michael Chabon A man bears witness to his grandfather's deathbed confessions, which reveal his family's long- buried history and his involvement in a mail-order novelty company, World War II, and the space program. OTHER BOOKS BY MICHAEL CHABON: The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (1988), A Model World and Other Stories (1991), Werewolves in their Youth (1999), The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (2000)*, Wonder Boys (2002), Summerland (2002), The Final Solution (2004)*, The Yiddish Policemen's Union (2007)*, Gentlemen of the Road (2007)*, Maps & Legends (2008)*, Manhood for Amateurs (2009)*, and Telegraph Avenue (2012).* READ-ALIKES: The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow* Refusing to submit to specialization, Augie March wanders from job to job, experiencing life in its fullness. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr A blind French girl on the run from the German occupation and a German orphan-turned-Resistance tracker struggle with their respective beliefs after meeting on the Brittany coast. The Angel of Losses by Stephanie Feldman* When she discovers her grandfather's notebook, which is filled with stories of a miracle worker named the White Rebbe in league with the mysterious Angel of Losses, Marjorie embarks on a journey into the past to unlock the secrets he kept. Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer* Follows a young writer on his travels through Eastern Europe in search of the woman who saved his grandfather from the Nazis, and guided by his Ukrainian translator, he discovers a past that will resonate far into the future. -

Experienceprinceton

ExperiencePrinceton: DIVERSEPERSPECTIVES The Right Will I fit in here? Question to Ask The Right Question As you think about where to go to college, we expect one of the big questions on your mind is this: “Will I fit in here?” Perhaps the question first occurred to you when to Ask you were doing online research or when you visited a college and observed a classroom, talked to a professor, reached out to a current student, went to a dining hall or attended an athletic event. It’s the right question to ask. At Princeton, we work hard to ensure that our students succeed not only academically but also in every other way. Wherever you go on our campus, you will find others who share your values, heritage and interests, as well as those who don’t. And just as important, when you don’t, you will find students and faculty who are interested in what makes you tick and are open to hearing about your experiences. We believe this is the time of your life to grow in every way. While you value where you came from, you no doubt are seeking a learning experience that will take you someplace you have never been — intellectually, emotionally and physically. Our driving philosophy is to ensure an environment where you will be comfortable and challenged. We spend many months seeking students who will help us build a community that is as diverse and intellectually stimulating as possible. Living and learning in such a rich cultural environment will transform your life. Within these pages, you will see how our community comes together. -

THE POST KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 1908 Newsstand 10£ Per Copy School Budget Is Cut

THE POST KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 1908 Newsstand 10£ per copy School Budget Is Cut $45,877 Deleted, New Election Set Next Week At a special meeting conducted last Friday, the South,Brunswick Board of Education voted to re NICHOLAS MAUL duce the 1968-69 school budget of EDGAR RENK JAMES McNALLEN $4,076,115, by $45,877 before re submitting it to the voters on Wednesday, Feb, 28. The vote was 7 -2 , with M rs. Jaycees Name Five JudgesCarolyn McCallum and James Wachtel casting the negative votes, explaining they considered the cuts Soldier Gives His Life, Comes Home excessive. However, through aseparate de An Army honor guard carries the flag-draped coffin of Timothy Ochs, who To SelectrOutstanding Man cision by the Township Committee was killed in Viet Nam, at Franklin Memorial Park Saturday, Specialist the previous Saturday, it appears Ochs, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Carl F; Ochs of Dayton, received full mil The names of the five judges that the local tax levy may be re tion. He Is also a past master last year’ s Outstanding Young Man itary honors at the funeral. who will select South Brunswick's duced by almost one-quarter mil of Pioneer Grange. awards "Outstanding Young'Man of 1967" lion dollars. Mr. McNallen, a Junior Cham were released this week by the An attorney practicing in New The Township Committeo In ber International Senator,Is a past South Brunswick Jaycees, who Brunswick, M r. Greene has served cluded In Its budget a $206,000 president of the South Brunswick sponsor the annual honor. -

![A Companion to American Literature]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2424/a-companion-to-american-literature-3252424.webp)

A Companion to American Literature]

Journal of Transnational American Studies 10.2 (Winter/Spring 2019–20) Reprise Connecting a Different Reading Public: Compiling [A Companion to American Literature] Yu Jianhua Shanghai International Studies University At the end of 2015, ten years after the project was initiated, A Companion to American Literature was finally published by Commercial Press in Beijing. This was the first attempt in Chinese academia at compiling a large-scale handbook covering foreign literature published in China and in Chinese. The Companion provides readers in China with easy access to sources in order for them to gain a better understanding of three hundred years of American literature. It includes well-known authors and their major works, literary historians and critics, literary journals, awards, organizations and movements, as well as terminologies such as “tall tale” and “minstrel show” that are unique to American literature. We started in a small way in 2003 after a suggestion from Fudan University Press that we provide a handy companion on American literature for Chinese undergraduates and graduate students. After American Literature: Authors and Their Works was published in 2005, a more ambitious plan emerged for a new handbook that was to be more comprehensive, and one that was to be written in Chinese for Chinese readers. The proposition received financial support from the Shanghai International Studies University Research Fund, and later, The National Social Science Fund of China, with more than thirty professors and young scholars participating in the project. After decisions were made in regard to the general layout and entries, we set to work, each responsible for an area that he or she specialized in, and together we contributed to the project that came to fruition ten years later. -

The Tourism of Titillation in Tijuana and Niagara Falls: Cross-Border Tourism and Hollywood Films Between 1896 and 1960"

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Érudit Article "The Tourism of Titillation in Tijuana and Niagara Falls: Cross-Border Tourism and Hollywood Films between 1896 and 1960" Dominique Brégent-Heald Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 17, n° 1, 2006, p. 179-203. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/016107ar DOI: 10.7202/016107ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 9 février 2017 10:21 The Tourism of Titillation in Tijuana and Niagara Falls: Cross-Border Tourism and Hollywood Films between 1896 and 1960 DOMINIQUE BRÉGENT-HEALD Abstract In the popular imaginary, Tijuana, Mexico is notorious for its liberal laws concerning prostitution, gambling, and narcotics. Conversely, Niagara Falls, Canada apparently offers visitors only wholesome attractions. Yet this sweep- ing generalization belies the historic parallels that exist between these iconic border towns. -

Frankl in Fiction: Logotherapy in Selected Works of Saul Bellow

FRANKL IN FICTION: LOGOTHERAPY IN SELECTED WORKS OF SAUL BELLOW A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of California State University Dominguez Hills In Pa1tial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Humanities by Aaron Lowers Fall 2016 Copyright by AARON LOWERS 2016 All Rights Reserved In loving memory of my mother, Diana, without whom this work would not have been possible . 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to acknowledge my mentor and thesis committee chair, Patricia Cherin, for her constant encouragement and insightful advice . I want to thank Reality Thornewood whose research assistance made this work possible. I want to aclmowledge Cory Dauer and Sharon Dias for adjusting my work schedule to allow me to pursue my studies. I also want to thank Emiliano Lopez , M. Medonis and B. Cruz for their technical assistance. Finally, I want to thank my family for their understanding and patience throughout this process. l V TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE COPYRIGHT·PAGE ............................................................. .................................. ............ ii DEDICATION ................... .......................... ................................................................. ..... iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................. ........ .......................... ................ iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................ ..................................................... v ABSTRACT ...................... .................................. ....................... -

Research on Jewish American Writers in Recent Ten Years

ISSN 1712-8358[Print] Cross-Cultural Communication ISSN 1923-6700[Online] Vol. 11, No. 12, 2015, pp. 96-98 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/8076 www.cscanada.org Research on Jewish American Writers in Recent Ten Years XU Li[a],* [a]Foreign Language Teaching Department, Inner Mongolia University Workshop at the University of Iowa. Jonathan Safran Foer for the Nationalities, Tongliao, China. is best known for his novels Everything Is Illuminated *Corresponding author. (2002), Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2005), Supported by the Scientific Research Funds Project of Inner Mongolia and for his non-fiction work Eating Animals (2009). He University for the Nationalities “Research on the Jewish American teaches creative writing at New York University. Michael Fictions in the Recent Ten Years” (NMDYB15056). Chabon is the bestselling and Pulitzer Prize-winning Received 8 October 2015; accepted 12 December 2015 author of The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, A Model World, Published online 26 December 2015 Wonder Boys, Werewolves in Their Youth, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, The Final Solution, Abstract The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, Maps and Legends, In recent ten years, Jewish American writers emerge in Gentlemen of the Road, and the middle grade book large numbers. Among them, Nathan Englander, Jonathan Summerland. He altogether writes 10 fictions till now. Safran Foer and Michael Chabon are distinguished and His fictions involve intense male-male relationships and popular among the readers. Their fictions represent the his work has become increasingly and explicitly Jewish- third generation of the Jewish writers and have their own centered. There are also some specific topics in his fiction, characteristics, such as holocaust, Jewish identity and such as Holocaust in Chabon’s fiction or his depiction of Jewish problems and so on.