The First Anglo-Afghan War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resettlement Policy Framework

Khyber Pass Economic Corridor (KPEC) Project (Component II- Economic Corridor Development) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Peshawar Public Disclosure Authorized March 2020 RPF for Khyber Pass Economic Corridor Project (Component II) List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank AH Affected household AI Access to Information APA Assistant Political Agent ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan BHU Basic Health Unit BIZ Bara Industrial Zone C&W Communication and Works (Department) CAREC Central Asian Regional Economic Cooperation CAS Compulsory acquisition surcharge CBN Cost of Basic Needs CBO Community based organization CETP Combined Effluent Treatment Plant CoI Corridor of Influence CPEC China Pakistan Economic Corridor CR Complaint register DPD Deputy Project Director EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA Environmental Protection Agency ERRP Emergency Road Recovery Project ERRRP Emergency Rural Road Recovery Project ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FBR Federal Bureau of Revenue FCR Frontier Crimes Regulations FDA FATA Development Authority FIDIC International Federation of Consulting Engineers FUCP FATA Urban Centers Project FR Frontier Region GeoLoMaP Geo-Referenced Local Master Plan GoKP Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa GM General Manager GoP Government of Pakistan GRC Grievances Redressal Committee GRM Grievances Redressal Mechanism IDP Internally displaced people IMA Independent Monitoring Agency -

The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War

wbhr 1|2012 The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War JIŘÍ KÁRNÍK Afghanistan is a beautiful, but savage and hostile country. There are no resources, no huge market for selling goods and the inhabitants are poor. So the obvious question is: Why did this country become a tar- get of aggression of the biggest powers in the world? I would like to an- swer this question at least in the first case, when Great Britain invaded Afghanistan in 1839. This year is important; it started the line of con- flicts, which affected Afghanistan in the 19th and 20th century and as we can see now, American soldiers are still in Afghanistan, the conflicts have not yet ended. The history of Afghanistan as an independent country starts in the middle of the 18th century. The first and for a long time the last man, who united the biggest centres of power in Afghanistan (Kandahar, Herat and Kabul) was the commander of Afghan cavalrymen in the Persian Army, Ahmad Shah Durrani. He took advantage of the struggle of suc- cession after the death of Nāder Shāh Afshār, and until 1750, he ruled over all of Afghanistan.1 His power depended on the money he could give to not so loyal chieftains of many Afghan tribes, which he gained through aggression toward India and Persia. After his death, the power of the house of Durrani started to decrease. His heirs were not able to keep the power without raids into other countries. In addition the ruler usually had wives from all of the important tribes, so after the death of the Shah, there were always bloody fights of succession. -

The Causes of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, a Probe Into the Reality of the International Relations in Central Asia in the Second Half of the 19Th Century1

wbhr 01|2014 The Causes of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, a Probe into the Reality of the International Relations in Central Asia in the Second Half of the 19th Century1 JIŘÍ KÁRNÍK Institute of World History, Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague Nám. J. Palacha 2, 116 38 Praha, Czech Republic [email protected] Central Asia has always been a very important region. Already in the time of Alexander the Great the most important trade routes between Europe and Asia run through this region. This importance kept strengthening with the development of the trade which was particularly connected with the famous Silk Road. Cities through which this trade artery runs through were experiencing a real boom in the late Middle Ages and in the Early modern period. Over the wealth of the business oases of Khiva and Bukhara rose Samarkand, the capital city of the empire of the last Great Mongol conqueror Timur Lenk (Tamerlane).2 The golden age of the Silk Road did not last forever. The overseas discoveries and the rapid development of the transoceanic sailing was gradually weakening the influence of this ancient trade route and thus lessening the importance and wealth of the cities and areas it run through. The profits of the East India companies were so huge that it paid off for them to protect their business territories. In the name of the trade protection began also the political penetration of the European powers into the overseas areas and empires began to emerge. 1 This article was created under project British-Afghan relations in 19th century which is dealt with in 2014 at Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague with funds from Charles University Grant Agency. -

'Great Game': the Russian Origins of the Second Anglo-Afghan

Beyond the ‘Great Game’: the Russian origins of the second Anglo-Afghan War* ALEXANDER MORRISON Department of History, Philosophy and Religious Studies, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nazarbayev University, Astana, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Abstract Drawing on published documents and research in Russian, Uzbek, British and Indian archives, this article explains how a hasty attempt by Russia to put pressure on the British in Central Asia unintentionally triggered the second Anglo-Afghan War of 1878 - 80. This conflict is usually interpreted within the framework of the so-called 'Great Game', which assumes that only the European 'Great Powers' had any agency in Central Asia, pursuing a coherent strategy with a clearly-defined set of goals and mutually-understood rules. The outbreak of the Second Anglo-Afghan war is usually seen as a deliberate attempt by the Russians to embroil the British disastrously in Afghan affairs, leading to the eventual installation of 'Abd al-Rahman Khan, hosted for many years by the Russians in Samarkand, on the Afghan throne. In fact the Russians did not foresee any of this. ‘Abd al-Rahman’s ascent to the Afghan throne owed nothing to Russian support, and everything to British desperation. What at first seems like a classic 'Great Game' episode was a tale of blundering and unintended consequences on both sides. Central Asian rulers were not merely passive bystanders who provided a picturesque backdrop for Anglo-Russian relations, but important actors in their own right. Introduction ‘How consistent and pertinacious is Russian policy! How vacillating and vague is our own!' Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1885.1 At the crossroads of Sary-Qul, near the village of Jam, at the south-western edge of the Zarafshan valley in Uzbekistan, there is an obelisk built of roughly-squared masonry, with a rusting cross embedded near the top. -

Kandahar Survey Report

Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report February 1996 AREA Office 17 - E Abdara Road UfTow Peshawar, Pakistan Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report Prepared by Eng. Yama and Eng. S. Lutfullah Sayed ·• _ ....... "' Content - Introduction ................................. 1 General information on Kandahar: - Summery ........................... 2 - History ........................... 3 - Political situation ............... 5 - Economic .......................... 5 - Population ........................ 6 · - Shelter ..................................... 7 -Cost of labor and construction material ..... 13 -Construction of school buildings ............ 14 -Construction of clinic buildings ............ 20 - Miscellaneous: - SWABAC ............................ 2 4 -Cost of food stuff ................. 24 - House rent· ........................ 2 5 - Travel to Kanadahar ............... 25 Technical recommendation .~ ................. ; .. 26 Introduction: Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan/ AREA intends to undertake some rehabilitation activities in the Kandahar province. In order to properly formulate the project proposals which AREA intends to submit to EC for funding consideration, a general survey of the province has been conducted at the end of Feb. 1996. In line with this objective, two senior staff members of AREA traveled to Kandahar and collect the required information on various aspects of the province. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

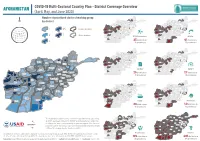

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

The Informal Regulation of the Onion Market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About Us

Researching livelihoods and Afghanistan services affected by conflict Kabul Jalalabad The social life of the Nangarhar Pakistan onion: the informal regulation of the onion market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations. Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals and international efforts at peace- building and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), Focus1000 in Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), -

“Othering” Oneself: European Civilian Casualties and Representations of Gendered, Religious, and Racial Ideology During the Indian Rebellion of 1857

“OTHERING” ONESELF: EUROPEAN CIVILIAN CASUALTIES AND REPRESENTATIONS OF GENDERED, RELIGIOUS, AND RACIAL IDEOLOGY DURING THE INDIAN REBELLION OF 1857 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Florida Gulf Coast University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters of Arts in History By Stefanie A. Babb 2014 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in History ________________________________________ Stefanie A. Babb Approved: April 2014 _________________________________________ Eric A. Strahorn, Ph.D. Committee Chair / Advisor __________________________________________ Frances Davey, Ph.D __________________________________________ Habtamu Tegegne, Ph.D. The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Copyright © 2014 by Stefanie Babb All rights reserved One must claim the right and the duty of imagining the future, instead of accepting it. —Eduardo Galeano iv CONTENTS PREFACE v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 CHAPTER TWO LET THE “OTHERING” BEGIN 35 Modes of Isolation 39 Colonial Thought 40 Racialization 45 Social Reforms 51 Political Policies 61 Conclusion 65 CHAPTER THREE LINES DRAWN 70 Outbreak at Meerut and the Siege on Delhi 70 The Cawnpore Massacres 78 Changeable Realities 93 Conclusion 100 CONCLUSION 102 APPENDIX A MAPS 108 APPENDIX B TIMELINE OF INDIAN REBELLION 112 BIBLIOGRAPHY 114 v Preface This thesis began as a seminar paper that was written in conjunction with the International Civilians in Warfare Conference hosted by Florida Gulf Coast University, February, 2012. -

New Great Game and Limits of American Power

38 IPRI Journal XIV,New no.Great 1 (WinterGame and 2014): Limits 38 of- 65American Power New Great Game and Limits of American Power Air Cdre. (R) Naveed Khaliq Ansaree Abstract The „New Great Game‟ is the global rivalry between the US- NATO bloc and its allies and their Counter-Alliance Camp. In the grand strategic calculus of Russia-China-Pakistan- Afghanistan-India entanglement, the US Camp seems to be losing its strategic foothold, particularly in Eurasia. The US‟ „Pivot to Asia‟ may also suffer serious setbacks. The deals on Syria‟s chemical weapons and Iran‟s nuclear programme have brought the Middle East under a „Strategic Pause‟ but have also exposed the limits of American power. Afghanistan is on the tipping-point of proving or disproving to be the „graveyard of empires‟. The danger of Saudi Arabia becoming the victim of a fresh „Arab Spring‟ as well as destabilization of Pakistan has increased manifold. The US‟ latest offer for full-spectrum revival of strategic alliance could merely be a „Strategic Deception‟ for Pakistan. The US-Iran nuclear deal may also manifest into additional space for US strategy and lines of operations for Afghanistan-Pakistan. Iran and Syria could be re-visited in the next cycle. Strategic wisdom is hoped to prevail amongst regional stake-holders. Any strategic failure of the US strategy could further expose the limits of American power. The dynamics could roll the ball for a new balance of power; thus shrinking the area of US imperialism and opening up spaces for the manifestation of „Chi-Merica‟ (China- America) or a multi-polar world. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina