Intellectual Property and Global Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life-Members

Life Members SUPREME COURT BAR ASSOCIATION Name & Address Name & Address 1 Abdul Mashkoor Khan 4 Adhimoolam,Venkataraman Membership no: A-00248 Membership no: A-00456 Res: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Res: "Prashanth", D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 110048 Tel: 09810857589 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Res: 328,Khan Medical Complex,Khair Nagar Fax: 41630065 Gate,Meerut,250002 Off: D-17, G.K. Enclave-I, New Delhi 110048 Tel: 0120-2423711 Tel: 011-26241780,41630065 Off: Apartment No.202, Tower No.4,, SCBA Noida Ch: 104,Lawyers Chamber, A.K.Sen Block, Supreme Project Complex, Sector - 99,, Noida 201303 Court of India, New Delhi 110001 Tel: 09810857589 Mobile: 9958922622 Mobile: 09412831926 Email: [email protected] 2 Abhay Kumar 5 Aditya Kumar Membership no: A-00530 Membership no: A-00412 Res: H.No.1/12, III Floor,, Roop Nagar,, Delhi Res: C-180,, Defence Colony, New Delhi 110024 110007 Off: C-13, LGF, Jungpura, New Delhi 110014 Tel: 24330307,24330308 41552772,65056036 Tel: 011-24372882 Tel: 095,Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: 104, Lawyers Chamber, Supreme Court of India, Ch: New Delhi 110001 New Delhi 110001 23782257 Mobile: 09810254016,09310254016 Tel: Mobile: 9911260001 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3 Abhigya 6 Aganpal,Pooja (Mrs.) Membership no: A-00448 Membership no: A-00422 Res: D-228, Nirman Vihar, Vikas Marg, Delhi 110092 Res: 4/401, Aganpal Chowk, Mehrauli, New Delhi Tel: 22432839 110030 Off: 704,Lawyers Chamber, Western Wing, Tis Hazari -

Abs Stop Sign Mp3, Flac, Wma

Abs Stop Sign mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop Album: Stop Sign Country: Australia Released: 2003 Style: Europop, Breakbeat, Electro MP3 version RAR size: 1422 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1715 mb WMA version RAR size: 1422 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 892 Other Formats: RA FLAC APE AAC MOD MP2 XM Tracklist Hide Credits Stop Sign Arranged By [Arrangement Input By] – A. Harrison*, G. Simmons*Backing Vocals – 1 Tracy AckermanMixed By – Absolute , Steve FitzmauriceProducer, Instruments [All 2:56 Instruments] – Absolute Written-By – Watkins*, O'Connell*, Sechleer*, Wynn*, Wilson*, Breen* Music For Cars Backing Band – Abs Backing Vocals – Richard "Biff" Stannard*Mixed By – Alvin 2 SweeneyProducer – Alvin Sweeney, Julian Gallagher, Richard "Biff" 3:02 Stannard*Programmed By – Julian GallagherWritten-By – Alvin Sweeney, Julian Gallagher, R. Breen*, Richard "Biff" Stannard* Stop That Bitchin' Backing Vocals – Shernette MayMixed By – Alvin SweeneyProducer, Instruments [All 3 Instruments] – Julian Gallagher, Richard "Biff" Stannard*Programmed By – Alvin 3:16 Sweeney, Julian Gallagher, Richard "Biff" Stannard*Written-By – Julian Gallagher, R. Breen*, Richard "Biff" Stannard* Video Stop Sign Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Copyright (c) – BMG UK & Ireland Ltd. Licensed From – Nestshare Ltd. Manufactured By – BMG Australia Limited Distributed By – BMG Australia Limited Pressed By – Technicolor, Australia Produced For – Biffco Productions Mixed At – Biffco Studios, Dublin Published -

Action Figures

Action Figures Star Wars (Kenner) (1977-1983) Power of the Force Complete Figures Imperial Dignitary Masters of the Universe (1982-1988) Wave 1 Complete Figures Battle Ram (Vehicle) Castle Grayskull (Playset) Accessories Man-At-Arms - Mini-comic (The Vengeance of Skeletor), Mace, Leg Armor Zodac - Mini-comic (The Vengeance of Skeletor or Slave City!) Beast Man - Whip, Spiked Arm Band, Spiked Arm Band Mer-Man - Mini-comic Teela - Snake Staff Wave 2 Accessories Trap Jaw - Mini-comic (The Menace of Trap Jaw!), Hook Arm, Rifle Arm Wave 3 Complete Figures Battle Armor He-Man Mekaneck (figure and accessories detailed below) Accessories Battle Armor Skeletor - Ram Staff Webstor - Grapple Hook with string Fisto - Sword Orko - Mini-comic (Slave City!), Magic Trick Whiplash - Mini-comic (The Secret Liquid of Life) Weapons Pack - Yellow Beast Man Chest Armor, Yellow Beast Man Arm Band, Gray Grayskull Shield, Gray Grayskull Sword Mekaneck - Club, Armor Wave 4 Complete Figures Dragon Blaster Skeletor (figure and accessories detailed below) Moss Man (figure and accessories detailed below) Battle Bones (Creature) Land Shark (Vehicle) Accessories Dragon Blaster Skeletor - Sword, Chest Armor, Chain, Padlock Hordak - Mini-comic (The Ruthless Leader's Revenge) Modulok - 1 Tail, Left Claw Leg Moss Man - Brown Mace Roboto - Mini-comic (The Battle for Roboto) Spikor - Mini-comic (Spikor Strikes) Fright Zone - Tree, Puppet, Door Thunder Punch He-Man - Shield Wave 5 Complete Figures Flying Fists He-Man Horde Trooper (figure and accessories detailed below) Snout -

2015 New Year Day Annadana Sponsors

2015 New Year Day Annadana Sponsors Grand Sponsor Nandakumar & Family Platinum Sponsors Jaya & Family Krishnan‐Shah Family Foundation Polavali Family Venkat Rangan Gold Sponsors Ambica & Kiran Badi Amgen Foundation Ananya Mishra Anil & Divya Kundhur Reddy Anonymous Ashok & Uma Shetty Family Blessings to Upadhyayula Family from Srimathi Santhanam Debu Chatterjee & Family Durga Natesan Gautam Varadan Geetika, Durga, Annapurna & Venkatadri Bobba Gopal Jayaraman Happy Birthday Hasini Hemalatha Balasubramanian Himabindu,Srinivas Paranthanate Family In Honor of Rememberance of Mrs. Mohini Mahtaney and Mrs. Amrutha Rai In Memory of Late Col Virender Sawhney K R Sridhar Kolan Suresh Reddy & Family Krish Venkataraman Lakshman N Yagati & Family Mahadevan Narayanan & Family Muthuraman S Iyer Namineni Family Nandakumar Thiruvoipati & Family Narasimhan Ganesh & Family Nilesh Ashok Patel Pavan & Lavanya Piratla Pavan Kumar Davuluri & Family Prabhavathi, Narasimha Murthy Malladi, Rajeshwari & Ramurthy Kuppa Prasad K Narayana Prasad K Narayana Prem Jhamandas Hinduja R K & Nina Anand Family Raghavan Srinivasan & Family Rajan & Latha Rajan Govinda Lakshminarasimhan & Family Rajesh & Anjali Nair Family Rajesh Mohan Rajesh Namdev & Family Ram Gurunathan & Family Ramarao Venkata Velpuri Family Ramesh A Iyer & Family Rashida & Ravi Ramakrishnan Ravi, Gowri, Rohit & Rohan Jonnalagadda Ravikanth Ummaneni & Family Ria Bhakta Ritsnet Inc Sampath Ramakrishnan Seetharaman Ramasubramani Shantha N Ursell ShyamSundar Challa Sraavya & Soumya Kakarlapudi Sreelakshmi, -

Jayal Amin Attorney at Law Phone: 847.230.0076 | Fax: 847.232.9303 PAGE: 2

PAGE: 1 Jayal Amin Attorney At Law Phone: 847.230.0076 | Fax: 847.232.9303 www.aminesq.com PAGE: 2 AMIN LAW OFFICES , LTD . Estate Planning • Wills/Revocable Living Trusts • Life Insurance Trusts • Irrevocable Trusts • Family Limited Partnerships • Probate / Trust Administration • Charitable Planning • Guardianship • Special Needs Planning Asset Protection Planning • Limited Liability Companies • Domestic Asset Protection Trusts • Oshore Asset Protection Trusts Jayal Amin Attorney At Law 1900 E. Golf Road– Suite 1120 • Schaumburg, IL 60173 Phone: 847.230.0076 | Fax: 847.232.9303 www.aminesq.com PAGE: 3 PROGRAM Master of Ceremony Sonal Aggarwal & Annita John, M.D. Social Hour and Exhibitor display 5:30 p.m. – 7:00 p.m National Anthems Annita John M.D. and Radhika Chimata, M.D. IAMA Business Meeting Suneela Harsoor, M.D. Secretary IAMA President’s Address Niranjana Shah, M.D. IAMACF Chairperson’s Address Lalitha Darbha, M.D., FACP Keynote Speaker’s Address Suja Mathew, M.D., FACP Chairman, Dept of Medicine, John H Stoger Jr Hospital Chief Guest George Dunea, M.D. President & CEO, Hektoen Institute Guest of Honors John Jay Shannon, M.D. Upendranath Nimmagadda, M.D. Dedication to Usharani Nimmagadda, M.D. Recognition Awards Vote of Thanks : Sonali Srinath, R.N., FNP Entertainment : Stand Up comedian Sonal Aggarwal Dinner Live DJ : DJ Saahil IAMACF MISSION The Clinic is committed to providing the basic primary health care, preventive medical care, public health education & community health care research with dignity & respect. PAGE: 4 Indian American Medical Association – Illinois Executive Committee 2019 Name Position Niranjana Shah, M.D. President Geeta Wadhwani, M.D. -

Constant Motion

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Constant Motion Daniel Rowe Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3120 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Daniel Rowe 2013 All Rights Reserved Constant Motion A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Kinetic Imaging at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Daniel Rowe Bachelor of Arts, Massachusetts College of Art, 2007 Director: Bob Paris, Associate Professor, Kinetic Imaging Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia May, 2013 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my father, Thomas, and mother, Dara, for showing me how to die with grace and how to keep living, respectively. I would like to thank Claire Krueger and Joseph Minek for their invaluable help and support through the Thesis Exhibition process. I would also like to thank Semi Ryu, Stephen Vitiello, Liz Canfield, Bob Paris, Pamela Turner, Sonali Gulati and Gretchen Soderlund for collectively teaching me how to write again. Finally, I would like to thank Ramona Rowe and Mika Rowe, my wonderful nieces and constant -

Women in Higher Education in India

Women in Higher Education in India Women in Higher Education in India: Perspectives and Challenges Edited by Hari Ponnamma Rani and Madhavi Kesari Women in Higher Education in India: Perspectives and Challenges Edited by Hari Ponnamma Rani and Madhavi Kesari This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Hari Ponnamma Rani, Madhavi Kesari and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0854-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0854-5 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................ 1 Streeling-Punling-Samething H.P. Rani, G. Siranjeevi, B. Sai Krishna Chapter Two ................................................................................................ 8 Transforming the Identity of Women—From Tradition to Modernity— Through Cinema: Towards Gender Equality Madhavi Kesari Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 14 Gender Discrimination in India: A Fly in the Ointment Suneetha Yedla, Sailaja Mukku Chapter Four ............................................................................................. -

ICCIASH-2020 PROCEEDINGS.Pdf

St. MARTIN’S ENGINEERING COLLEGE An Autonomous Institute A Non Minority College | Approved by AICTE | Affiliated to JNTUH, Hyderabad | NAAC-Accredited„A+‟ Grade|2(f)&12(B)status(UGC)ISO9001:2008 Certified| NBA Accredited | SIRO (DSIR) | UGC-Paramarsh | Recognized Remote Center of IIT, Bombay Dhulapally, Secunderabad – 500100, Telangana State, India. www.smec.ac.in Department of Science & Humanities International Conference on “Continuity, Consistency and Innovation in Applied Sciences and Humanities” on 13th & 14th August 2020 (ICCIASH – 20) Editor in Chief Dr. P. Santosh Kumar Patra Principal, SMEC Editor Dr. Ranadheer Reddy Donthi Professor & Head, Dept. of S&H, SMEC Editorial Committee Dr. A. Aditya Prasad, Professor, S&H Dr. N. Panda, Professor, S&H Dr. S. Someshwar, Associate Professor,S&H Dr. Andrea S. C. D’Cruz, Associate Professor, S&H Dr. Venkanna, Associate Professor, S&H Mr. S. Malli Babu, Associate Professor, S&H Mr.K.Sathish,AssistantProfessor,S&H ISBN No. 978-93-88096-42-3 St. MARTIN’S ENGINEERING COLLEGE Dhulapally, Secunderabad - 500100 NIRF ranked, NAAC A+ ACCREDITED M. LAXMAN REDDY CHAIRMAN MESSAGE I am extremely pleased to know that the department of Science & Humanities of SMEC is organizing Online International Conference on “Continuity, Consistency and Innovation in Applied Sciences and Humanities (ICCIASH-2020)” on 13th and 14th August, 2020. I understand that large number of researchers have submitted their research papers for presentation in the conference and also for publication. The response to this conference from all over India and Foreign countries is most encouraging. I am sure all the participants will be benefitted by their interaction with their fellow researchers and engineers which will help for their research work and subsequently to the society at large. -

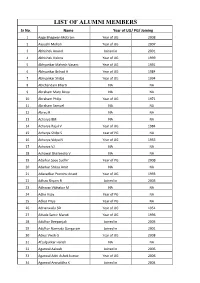

LIST of ALUMNI MEMBERS Sr No

LIST OF ALUMNI MEMBERS Sr No. Name Year of UG/ PG/ Joining 1 Aage Bhagwan Motiram Year of UG 2008 2 Aayushi Mohan Year of UG 2007 3 Abhishek Anand Joined in 2001 4 Abhishek Vishnu Year of UG 1999 5 Abhyankar Mahesh Vasant Year of UG 1991 6 Abhyankar Brihad A Year of UG 1984 7 Abhyankar Shilpa Year of UG 1994 8 Abichandani Bharti NA NA 9 Abraham Mary Binsu NA NA 10 Abraham Philip Year of UG 1971 11 Abraham Samuel NA NA 12 Abreu R NA NA 13 Acharya BM NA NA 14 Acharya Rajul V Year of UG 1984 15 Acharya Shilpi S Year of PG NA 16 Acharya Vidya N Year of UG 1955 17 Acharya VJ NA NA 18 Achawal Shailendra V NA NA 19 Adarkar Saee Sudhir Year of PG 2008 20 Adarkar Shilpa Amit NA NA 21 Adavadkar Pranshu Anant Year of UG 1993 22 Adhau Shyam R Joined in 2003 23 Adhavar Vibhakar M NA NA 24 Adhe Vijay Year of PG NA 25 Adkar Priya Year of PG NA 26 Adrianwalla SD Year of UG 1951 27 Adsule Samir Maruti Year of UG 1996 28 Adulkar Deepanjali Joined in 2005 29 Adulkar Namrata Gangaram Joined in 2001 30 Adwe Vivek G Year of UG 2008 31 Afzulpurkar Harish NA NA 32 Agarwal Aakash Joined in 2005 33 Agarwal Aditi Ashok kumar Year of UG 2006 34 Agarwal Aniruddha K Joined in 2004 35 Agarwal AVedprakash NA NA 36 Agarwal Bharat R NA NA 37 Agarwal CS NA NA 38 Agarwal Gayatri NA NA 39 Agarwal Hemant Shyam NA NA 40 Agarwal KK NA NA 41 Agarwal Krishnakumar NA NA 42 Agarwal Manit Sanjay Year of UG 2008 43 Agarwal Mohan B Year of UG 1970 44 Agarwal Nisha Rahul Year of PG MD PSM 09 45 Agarwal Parmanand Year of PG 2012 46 Agarwal Prakashchand G Year of UG 1998 47 Agarwal Rahul -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

July COF C1:Customer 6/7/2012 1:32 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18JUL 2012 JUL E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG 07 JULY COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 6/7/2012 12:16 PM Page 1 CAPTAIN AMERICA/IRON MAN” DUAL NATURE” GREY T-SHIRT Available only PREORDER NOW! from your local comic shop! BACK STAR WARS: “DARTH LUKE CAGE & POWER ADVENTURE TIME: VADER’S LAST STAND” MAN YELLOW T-SHIRT “WIGGLY LEGS COSTUME” WHITE T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! WHITE T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page July:gem page v18n1.qxd 6/7/2012 10:33 AM Page 1 THE SHAOLIN COWBOY GHOST #0 ADVENTURE MAGAZINE TP DARK HORSE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS TALON #0 DC COMICS STIEG LARSSON’S THE GIRL WITH THE STAR TREK: THE NEXT DRAGON TATTOO VOL. 1 HC GENERATION: HIVE #1 DC COMICS/VERTIGO IDW PUBLISHING GUARDING THE GLOBE #1 IMAGE COMICS ULTIMATE COMICS HAPPY! #1 ULTIMATES #16 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 6/7/2012 11:20 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS New Crusaders: Rise of the Heroes #1G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Wish You Were Here Volume 1 TP/HC G HALLOWEEN COMICSFEST G Halloween Mini Comics Mega Bundle 2012 PREVIEWS PUBLICATIONS 1 COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS 1 Sonic The Hedgehog: The Complete Comic Encyclopedia TP G ARCHIE COMICS Fashion Beast #1 G AVATAR PRESS The Simpsons‘ Treehouse of Horror #18 G BONGO COMICS The Lookouts: Riddle #1 G CRYPTOZOIC ENTERTAINMENT Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt #1 G D. -

'Writing' Media: an Investigation of Practical Production in Media Education by Secondary School Students

'WRITING' MEDIA: AN INVESTIGATION OF PRACTICAL PRODUCTION IN MEDIA EDUCATION BY SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS. BY JULIAN SEFTON-GREEN Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy in Education Institute ofEducation, University ofLondon January 1998 Abstract Chapter 1 provides an historical analysis ofthe role ofpractical production in media education in England. It discusses its varied educational aims. The need to consider practical work as a form of writing is advanced. Traditional notions of media education have possessed few theories of language and learning and have failed to conceptualise a relationship between critical understanding and making media. Discussion of 'media literacy' and 'visual literacy' is followed by an exploration of models of the writing process and the limits of the metaphor ofliteracy when applied to forms of media production. Selective accounts of theories ofwriting instruction (drawing upon models of the writing process), conclude that there are problems with the metaphor of media literacy. By contrast Cultural Studies has conceptualised creative productions by young people in terms that evoke notions of the written. The central research question is formulated in Chapter 2: what sense can we make ofmedia production using theories of writing; and thus by implication what change to such theories might be made using data drawn from educational research on media production? In Chapter 3 discussion of methodological questions draws attention to two traditions: Cultural Studies work on media audiences. and classroom based action research. Different methods of textual analysis are applied to media productions by young people in the next four chapters (4-7) within the specific histories of several classrooms in North London schools. -

Welcome to the Exalted 3E Homebrew Bestiary! By: an Idiot with Too Much Time on His Hands Sandact6

Welcome to the Exalted 3e Homebrew Bestiary! By: An idiot with too much time on his hands Sandact6 Hello everyone, and welcome to the unfiltered madness of my mind when I am left unchained and untethered to vomit forth words as I please. If you’re reading this, you are no doubt left wanting some monsters for your game. If that is the case feel free to scroll down and use them if you’re impatient. This introduction section will be short and sweet. We’ll be going over two optional components to this monster guide: Enemy Types and EX-Hard enemies. I also decided that this project would happen upon my 666th post on the OPP forums. So as you enjoy this document, settle in with those you truly care about while reading this manual. Having knowledge and comfort in that as the sky turns red on Christmas, my horrible form which cannot be described with any words shall make your death mercifully quick. Enemy Design Philosophy My goal for this monster manual, aside from just giving a wide array of baddies, is to make enemy design even more interesting in combat. Each enemy I’ll try to give some reason why you want that specific enemy dead the most in combat. Going beyond just mere filler enemies to make encounters interesting, and trying to make each monster interesting in a sense beyond that it's just a bag of numbers to overcome. New Enemy Classification Types People like to jump to conclusions. Did you know this section is optional and that you can totally ignore it and have this monster guide still work strictly RAW? Yes? Good.