Cell Cycle Control of Spindle Pole Body Duplication and Splitting by Sfi1 and Cdc31 in Fission Yeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ancestral Role of Pericentrin in Centriole Formation Through SAS-6 Recruitment

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/313494; this version posted May 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. An ancestral role of pericentrin in centriole formation through SAS-6 recruitment Daisuke Ito1*, Sihem Zitouni1, Swadhin Chandra Jana1, Paulo Duarte1, Jaroslaw Surkont1, Zita Carvalho-Santos1,2, José B. Pereira-Leal1, Miguel Godinho Ferreira1,3 and Mónica Bettencourt-Dias1* 1. Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Rua da Quinta Grande 6, Oeiras 2780-156, Portugal. 2. Present address: Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown, Lisbon, Portugal 3. Institute for Research on Cancer and Aging of Nice (IRCAN), INSERM U1081 UMR7284 CNRS, 06107 Nice, France *Correspondence to: [email protected] (DI); [email protected] (MBD) Running title: Ancestral role of pericentrin-SAS-6 interaction Key words: centrosome, centriole, fission yeast, SPB, SAS-6, pericentrin, calmodulin, evolution Short summary The pericentriolar matrix (PCM) is not only important for microtubule-nucleation but also can regulate centriole biogenesis. Ito et al. reveal an ancestral interaction between the centriole protein SAS-6 and the PCM component pericentrin, which regulates centriole biogenesis and elongation. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/313494; this version posted May 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract The centrosome is composed of two centrioles surrounded by a microtubule-nucleating pericentriolar matrix (PCM). Centrioles regulate matrix assembly. Here we ask whether the matrix also regulates centriole assembly. -

Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 T + is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 34 of which you can access for free at: 2016; 197:1477-1488; Prepublished online 1 July from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication 2016; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600589 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477 Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8 Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. Waugh, Sonia M. Leach, Brandon L. Moore, Tullia C. Bruno, Jonathan D. Buhrman and Jill E. Slansky J Immunol cites 95 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2016/07/01/jimmunol.160058 9.DCSupplemental This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2016 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 25, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. -

Identification of Genes Concordantly Expressed with Atoh1 During Inner Ear Development

Original Article doi: 10.5115/acb.2011.44.1.69 pISSN 2093-3665 eISSN 2093-3673 Identification of genes concordantly expressed with Atoh1 during inner ear development Heejei Yoon, Dong Jin Lee, Myoung Hee Kim, Jinwoong Bok Department of Anatomy, Brain Korea 21 Project for Medical Science, College of Medicine, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea Abstract: The inner ear is composed of a cochlear duct and five vestibular organs in which mechanosensory hair cells play critical roles in receiving and relaying sound and balance signals to the brain. To identify novel genes associated with hair cell differentiation or function, we analyzed an archived gene expression dataset from embryonic mouse inner ear tissues. Since atonal homolog 1a (Atoh1) is a well known factor required for hair cell differentiation, we searched for genes expressed in a similar pattern with Atoh1 during inner ear development. The list from our analysis includes many genes previously reported to be involved in hair cell differentiation such as Myo6, Tecta, Myo7a, Cdh23, Atp6v1b1, and Gfi1. In addition, we identified many other genes that have not been associated with hair cell differentiation, including Tekt2, Spag6, Smpx, Lmod1, Myh7b, Kif9, Ttyh1, Scn11a and Cnga2. We examined expression patterns of some of the newly identified genes using real-time polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization. For example, Smpx and Tekt2, which are regulators for cytoskeletal dynamics, were shown specifically expressed in the hair cells, suggesting a possible role in hair cell differentiation or function. Here, by re- analyzing archived genetic profiling data, we identified a list of novel genes possibly involved in hair cell differentiation. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Supplementary Table S1. Correlation Between the Mutant P53-Interacting Partners and PTTG3P, PTTG1 and PTTG2, Based on Data from Starbase V3.0 Database

Supplementary Table S1. Correlation between the mutant p53-interacting partners and PTTG3P, PTTG1 and PTTG2, based on data from StarBase v3.0 database. PTTG3P PTTG1 PTTG2 Gene ID Coefficient-R p-value Coefficient-R p-value Coefficient-R p-value NF-YA ENSG00000001167 −0.077 8.59e-2 −0.210 2.09e-6 −0.122 6.23e-3 NF-YB ENSG00000120837 0.176 7.12e-5 0.227 2.82e-7 0.094 3.59e-2 NF-YC ENSG00000066136 0.124 5.45e-3 0.124 5.40e-3 0.051 2.51e-1 Sp1 ENSG00000185591 −0.014 7.50e-1 −0.201 5.82e-6 −0.072 1.07e-1 Ets-1 ENSG00000134954 −0.096 3.14e-2 −0.257 4.83e-9 0.034 4.46e-1 VDR ENSG00000111424 −0.091 4.10e-2 −0.216 1.03e-6 0.014 7.48e-1 SREBP-2 ENSG00000198911 −0.064 1.53e-1 −0.147 9.27e-4 −0.073 1.01e-1 TopBP1 ENSG00000163781 0.067 1.36e-1 0.051 2.57e-1 −0.020 6.57e-1 Pin1 ENSG00000127445 0.250 1.40e-8 0.571 9.56e-45 0.187 2.52e-5 MRE11 ENSG00000020922 0.063 1.56e-1 −0.007 8.81e-1 −0.024 5.93e-1 PML ENSG00000140464 0.072 1.05e-1 0.217 9.36e-7 0.166 1.85e-4 p63 ENSG00000073282 −0.120 7.04e-3 −0.283 1.08e-10 −0.198 7.71e-6 p73 ENSG00000078900 0.104 2.03e-2 0.258 4.67e-9 0.097 3.02e-2 Supplementary Table S2. -

The Transformation of the Centrosome Into the Basal Body: Similarities and Dissimilarities Between Somatic and Male Germ Cells and Their Relevance for Male Fertility

cells Review The Transformation of the Centrosome into the Basal Body: Similarities and Dissimilarities between Somatic and Male Germ Cells and Their Relevance for Male Fertility Constanza Tapia Contreras and Sigrid Hoyer-Fender * Göttingen Center of Molecular Biosciences, Johann-Friedrich-Blumenbach Institute for Zoology and Anthropology-Developmental Biology, Faculty of Biology and Psychology, Georg-August University of Göttingen, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The sperm flagellum is essential for the transport of the genetic material toward the oocyte and thus the transmission of the genetic information to the next generation. During the haploid phase of spermatogenesis, i.e., spermiogenesis, a morphological and molecular restructuring of the male germ cell, the round spermatid, takes place that includes the silencing and compaction of the nucleus, the formation of the acrosomal vesicle from the Golgi apparatus, the formation of the sperm tail, and, finally, the shedding of excessive cytoplasm. Sperm tail formation starts in the round spermatid stage when the pair of centrioles moves toward the posterior pole of the nucleus. The sperm tail, eventually, becomes located opposed to the acrosomal vesicle, which develops at the anterior pole of the nucleus. The centriole pair tightly attaches to the nucleus, forming a nuclear membrane indentation. An Citation: Tapia Contreras, C.; articular structure is formed around the centriole pair known as the connecting piece, situated in the Hoyer-Fender, S. The Transformation neck region and linking the sperm head to the tail, also named the head-to-tail coupling apparatus or, of the Centrosome into the Basal in short, HTCA. -

Centrosome Remodelling in Evolution

cells Review Centrosome Remodelling in Evolution Daisuke Ito * ID and Mónica Bettencourt-Dias * Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Rua da Quinta Grande 6, 2780-156 Oeiras, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.I.); [email protected] (M.B.-D.) Received: 26 May 2018; Accepted: 4 July 2018; Published: 6 July 2018 Abstract: The centrosome is the major microtubule organizing centre (MTOC) in animal cells. The canonical centrosome is composed of two centrioles surrounded by a pericentriolar matrix (PCM). In contrast, yeasts and amoebozoa have lost centrioles and possess acentriolar centrosomes—called the spindle pole body (SPB) and the nucleus-associated body (NAB), respectively. Despite the difference in their structures, centriolar centrosomes and SPBs not only share components but also common biogenesis regulators. In this review, we focus on the SPB and speculate how its structures evolved from the ancestral centrosome. Phylogenetic distribution of molecular components suggests that yeasts gained specific SPB components upon loss of centrioles but maintained PCM components associated with the structure. It is possible that the PCM structure remained even after centrosome remodelling due to its indispensable function to nucleate microtubules. We propose that the yeast SPB has been formed by a step-wise process; (1) an SPB-like precursor structure appeared on the ancestral centriolar centrosome; (2) it interacted with the PCM and the nuclear envelope; and (3) it replaced the roles of centrioles. Acentriolar centrosomes should continue to be a great model to understand how centrosomes evolved and how centrosome biogenesis is regulated. Keywords: centrosome; centriole; spindle pole body; SPB; PCM; evolution 1. Introduction In 1887, the German biologist Theodor Boveri first described and named the structure at the pole of a mitotic spindle as “centrosome” [1]. -

E-Mutpath: Computational Modelling Reveals the Functional Landscape of Genetic Mutations Rewiring Interactome Networks

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262386; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. e-MutPath: Computational modelling reveals the functional landscape of genetic mutations rewiring interactome networks Yongsheng Li1, Daniel J. McGrail1, Brandon Burgman2,3, S. Stephen Yi2,3,4,5 and Nidhi Sahni1,6,7,8,* 1Department oF Systems Biology, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA 2Department oF Oncology, Livestrong Cancer Institutes, Dell Medical School, The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 3Institute For Cellular and Molecular Biology (ICMB), The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 4Institute For Computational Engineering and Sciences (ICES), The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 5Department oF Biomedical Engineering, Cockrell School of Engineering, The University oF Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 6Department oF Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Science Park, Smithville, TX 78957, USA 7Department oF BioinFormatics and Computational Biology, The University oF Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, USA 8Program in Quantitative and Computational Biosciences (QCB), Baylor College oF Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA *To whom correspondence should be addressed. Nidhi Sahni. Tel: +1 512 2379506; Email: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262386; this version posted August 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Suppl. Table 1

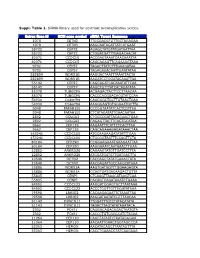

Suppl. Table 1. SiRNA library used for centriole overduplication screen. Entrez Gene Id NCBI gene symbol siRNA Target Sequence 1070 CETN3 TTGCGACGTGTTGCTAGAGAA 1070 CETN3 AAGCAATAGATTATCATGAAT 55722 CEP72 AGAGCTATGTATGATAATTAA 55722 CEP72 CTGGATGATTTGAGACAACAT 80071 CCDC15 ACCGAGTAAATCAACAAATTA 80071 CCDC15 CAGCAGAGTTCAGAAAGTAAA 9702 CEP57 TAGACTTATCTTTGAAGATAA 9702 CEP57 TAGAGAAACAATTGAATATAA 282809 WDR51B AAGGACTAATTTAAATTACTA 282809 WDR51B AAGATCCTGGATACAAATTAA 55142 CEP27 CAGCAGATCACAAATATTCAA 55142 CEP27 AAGCTGTTTATCACAGATATA 85378 TUBGCP6 ACGAGACTACTTCCTTAACAA 85378 TUBGCP6 CACCCACGGACACGTATCCAA 54930 C14orf94 CAGCGGCTGCTTGTAACTGAA 54930 C14orf94 AAGGGAGTGTGGAAATGCTTA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CCCGGTAATATCACTCGTTAA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CTCATAGATATTGAACAATAA 2802 GOLGA3 CTGGCCGATTACAGAACTGAA 2802 GOLGA3 CAGAGTTACTTCAGTGCATAA 9662 CEP135 AAGAATTTCATTCTCACTTAA 9662 CEP135 CAGCAGAAAGAGATAAACTAA 153241 CCDC100 ATGCAAGAAGATATATTTGAA 153241 CCDC100 CTGCGGTAATTTCCAGTTCTA 80184 CEP290 CCGGAAGAAATGAAGAATTAA 80184 CEP290 AAGGAAATCAATAAACTTGAA 22852 ANKRD26 CAGAAGTATGTTGATCCTTTA 22852 ANKRD26 ATGGATGATGTTGATGACTTA 10540 DCTN2 CACCAGCTATATGAAACTATA 10540 DCTN2 AACGAGATTGCCAAGCATAAA 25886 WDR51A AAGTGATGGTTTGGAAGAGTA 25886 WDR51A CCAGTGATGACAAGACTGTTA 55835 CENPJ CTCAAGTTAAACATAAGTCAA 55835 CENPJ CACAGTCAGATAAATCTGAAA 84902 CCDC123 AAGGATGGAGTGCTTAATAAA 84902 CCDC123 ACCCTGGTTGTTGGATATAAA 79598 LRRIQ2 CACAAGAGAATTCTAAATTAA 79598 LRRIQ2 AAGGATAATATCGTTTAACAA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TTGGATTTGTCTATACATATA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TAGACTTAGTATATAAATACA 2302 FOXJ1 CAGGACAGACAGACTAATGTA -

Migration of Thymic Pre-T Cells Regulates Development

Alternative Splicing Controlled by Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein L Regulates Development, Proliferation, and Migration of Thymic Pre-T Cells This information is current as of October 2, 2021. Marie-Claude Gaudreau, Florian Heyd, Rachel Bastien, Brian Wilhelm and Tarik Möröy J Immunol published online 20 April 2012 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2012/04/20/jimmun ol.1103142 Downloaded from Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2012/04/20/jimmunol.110314 Material 2.DC1 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Why The JI? Submit online. • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication by guest on October 2, 2021 *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2012 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Published April 20, 2012, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1103142 The Journal of Immunology Alternative Splicing Controlled by Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein L Regulates Development, Proliferation, and Migration of Thymic Pre-T Cells Marie-Claude Gaudreau,*,† Florian Heyd,‡ Rachel Bastien,* Brian Wilhelm,x and Tarik Mo¨ro¨y*,† The regulation of posttranscriptional modifications of pre-mRNA by alternative splicing is important for cellular function, devel- opment, and immunity. -

Application of Genomic Technologies to Study Infertility Nicholas Rui Yuan Ho Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2016 Application of Genomic Technologies to Study Infertility Nicholas Rui Yuan Ho Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, Genetics Commons, and the Molecular Biology Commons Recommended Citation Yuan Ho, Nicholas Rui, "Application of Genomic Technologies to Study Infertility" (2016). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 786. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/786 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences Computational and Systems Biology Dissertation Examination Committee: Donald Conrad, Chair Barak Cohen Joseph Dougherty John Edwards Liang Ma Application of Genomic Technologies to Study Infertility by Nicholas Rui Yuan Ho A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2016 St. Louis, Missouri © 2016, Nicholas Rui Yuan Ho Table of -

Plk4-Induced Centriole Biogenesis in Human Cells

Plk4-induced Centriole Biogenesis in Human Cells Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften der Fakultät für Biologie der Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München Vorgelegt von Julia Kleylein-Sohn München, 2007 Dissertation eingereicht am: 27.11.2007 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.04.2008 Erstgutachter: Prof. E. A. Nigg Zweitgutachter: PD Dr. Angelika Böttger 2 Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation selbständig und ohne unerlaubte Hilfe angefertigt habe. Sämtliche Experimente wurden von mir selbst durchgeführt, soweit nicht explizit auf Dritte verwiesen wird. Ich habe weder an anderer Stelle versucht, eine Dissertation oder Teile einer solchen einzureichen bzw. einer Prüfungskommission vorzulegen, noch eine Doktorprüfung zu absolvieren. München, den 22.11.2007 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………..………. 6 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………. 7 Structure of the centrosome…………………………………………………………….. 7 The centrosome cycle…………………………………………………………………..10 Kinases involved in the regulation of centriole duplication………………………….12 Maintenance of centrosome numbers………………………………………………...13 Licensing of centriole duplication……………………………………………………... 15 ‘De novo ’ centriole assembly pathways in mammalian cells…………………..…...15 Templated centriole biogenesis in mammalian cells……………………………….. 18 The role of centrins and Sfi1p in centrosome duplication ……………………...…..19 Centriole biogenesis in C. elegans …………………………………………………… 21 Centriole biogenesis in human cells………………………………………………….. 23 Centrosome