Charles Oman, the Great Revolt of 1381

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mayor and Early Lollard Dissemination

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2012 The mayor and early Lollard dissemination Angel Gomez University of Central Florida Part of the Medieval History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Gomez, Angel, "The mayor and early Lollard dissemination" (2012). HIM 1990-2015. 1774. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1774 THE MAYOR AND EARLY LOLLARD DISSEMINATION by ANGEL GOMEZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Emily Graham Abstract During the fourteenth century in England there began a movement referred to as Lollardy. Throughout history, Lollardy has been viewed as a precursor to the Protestant Reformation. There has been a long ongoing debate among scholars trying to identify the extent of Lollard beliefs among the English. Attempting to identify who was a Lollard has often led historians to look at the trial records of those accused of being Lollards. One aspect overlooked in these studies is the role civic authorities, like the mayor of a town, played in the heresy trials of suspected Lollards. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Christ Church Letters

C HR I T H R H L S C U C E TTE R S . A VOLUME OF MEDIE VAL LETTERS R E LATIN G TO THE A F F AI R S O F THE PR IORY O F C HRIST C HU RC H C ANTERBU RY . EDITED BY HEPPARD J. B. S , H AMDEN E PRINTED FOR T E C SOC I TY . D C C . XX . M . C L VII WE S TMINS TE R PR NTE D BY NIC HO LS AND O N I S S , 2 5 P R ME NT TR E E , A LIA S T. COUNCIL OF THE CAMDEN SOCIETY FO R THE Y EA R - 1 8 7 6 7 7 . ' - - Pq es i (i cnt, THE F U F . R RI . A L V LA M THE GHT HON E R O ER , T ea u e . WILLI A M HA LL E . C PPE , SQ r s r r N Y S . A . E R A LE ES . F . H CH R S COOTE , Q J A M GA IRDNER ES . ES , Q - A M U L RAWSON G A D I R ES D i ecto . S E R NE , Q , r r W'ILLIA M E NHA M L E O HEW ETT , SQ . ' AL F D KI G ES S ec retao . RE N STON , Q , y I H . A . S R J M A L A E. O N C E N , S V. P. A . F D I Y E . RE ER C OUVR , SQ S T \ HE AR L F P VIS LL. -

Chaucer's Official Life

CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE JAMES ROOT HULBERT CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE Table of Contents CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE..............................................................................................................................1 JAMES ROOT HULBERT............................................................................................................................2 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................4 THE ESQUIRES OF THE KING'S HOUSEHOLD...................................................................................................7 THEIR FAMILIES........................................................................................................................................8 APPOINTMENT.........................................................................................................................................12 CLASSIFICATION.....................................................................................................................................13 SERVICES...................................................................................................................................................16 REWARDS..................................................................................................................................................18 -

Community and Childrens Services Terms of Reference

WOOTTON, Mayor RESOLVED: That the Court of Common Council holden in the Guildhall of the City of London on Thursday 19th April 2012, doth hereby appoint the following Committee until the first meeting of the Court in April, 2013. COMMUNITY & CHILDREN’S SERVICES COMMITTEE 1. Constitution A Ward Committee consisting of, two Aldermen nominated by the Court of Aldermen up to 33 Commoners representing each Ward (two representatives for the Wards with six or more Members regardless of whether the Ward has sides), those Wards having 200 or more residents (based on the Ward List) being able to nominate a maximum of two representatives a limited number of Members co-opted by the Committee (e.g. the two parent governors required by law) In accordance with Standing Order Nos. 29 & 30, no Member who is resident in, or tenant of, any property owned by the City of London and under the control of this Committee is eligible to be Chairman or Deputy Chairman. 2. Quorum The quorum consists of any nine Members. [N.B. - the co-opted Members only count as part of the quorum for matters relating to the Education Function] 3. Membership 2012/13 ALDERMEN 1 The Hon. Philip John Remnant, C.B.E. 1 New Alderman for the Ward of Aldgate COMMONERS 7 The Revd. Dr. Martin Dudley ………………………………………………………………….Aldersgate 2 Joyce Carruthers Nash, O.B.E., Deputy .........................................................................Aldersgate 4 Hugh Fenton Morris .......................................................................................................Aldgate -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Sarah L. Peverley a Tretis Compiled out of Diverse Cronicles (1440): A

Sarah L. Peverley A Tretis Compiled out of Diverse Cronicles (1440): A Study and Edition of the Short English Prose Chronicle Extant in London, British Library, Additional 34,764 Sarah L. Peverley Introduction The short English prose chronicle extant in London, British Library, MS Additional 34,764 has never been edited or received any serious critical attention.1 Styled as ‘a tretis compiled oute of diuerse cronicles’ (hereafter Tretis), the text was completed in ‘the xviij yere’ of King Henry VI of England (1439–1440) by an anonymous author with an interest in, and likely connection with, Cheshire. Scholars’ neglect of the Tretis to date is largely attributable to the fact that it has been described as a ‘brief and unimportant’ account of English history, comprising a genealogy of the English kings derived from Aelred of Rievalux’s Genealogia regum Anglorum and a description of England abridged from Book One of Ranulph Higden’s Polychronicon.2 While the author does utilize these works, parts of the Tretis are nevertheless drawn from other sources and the combination of the materials is more sophisticated than has hitherto been acknowledged. Beyond the content of the Tretis, the manuscript containing it also needs reviewing. As well as being the only manuscript in which the Tretis has been identified to date, Additional 34,764 was once part of a (now disassembled) fifteenth- century miscellany produced in the Midlands circa 1475. The miscellany was 1 To date, the only scholar to pay attention to the nature of the text is Edward Donald Kennedy, who wrote two short entries on the chronicle (Kennedy 1989: 2665-2666, 2880-2881; 2010: 1). -

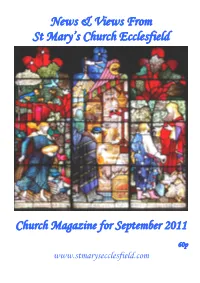

Front Cover- the Lower Left 3 Panels of the Parables of Nature (Gatty) Window 2

News & Views From St Mary’s Church Ecclesfield Church Magazine for September 2011 60p www.stmarysecclesfield.com First Words… Back To School – September is the “back to school” month. It’s also the month when lots of things get going again in the life of the Church. The changes that were outlined in last month’s magazine start to take shape in September. During this month we’ll start to think about the shape of our Joint Service. We’ll also start to plan our new After School Club. Harvest – This year we celebrate Harvest on 25th September with a Joint Service of Parish Communion at 10.30 a.m. Please come along and join with us. Celebration Weekend – A date for your diary. The weekend of 8/ 9 October will be a time of great celebration here in Ecclesfield. We will be celebrating the 700th anniversary of the first named Vicar of Ecclesfield and the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. Keep a look out in later magazines for further information. Daniel Hartley The Collect for Harvest Sunday Eternal God, you crown the year with your goodness and you give us the fruits of the earth in their season: grant that we may use them to your glory, for the relief of those in need and for our own well-being; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord, who is alive and reigns with you, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. Amen Front cover- The Lower Left 3 Panels of the Parables of Nature (Gatty) window 2 The Gatty Memorial Hall Priory Road Ecclesfield Sheffield S35 9XY Phone: 0114 246 3993 Accommodation now available for booking GROUPS • MEETINGS • ACTIVITIES FUNCTIONS Ecclesfield Church Playgroup The Gatty Memorial Hall Priory Road Ecclesfield A traditional playgroup for children 2½ to 5 years. -

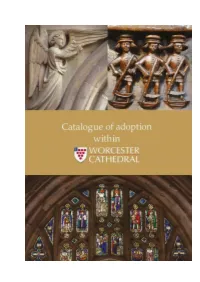

Catalogue of Adoption Items Within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window

Catalogue of Adoption Items within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window The cloister Windows were created between 1916 and 1999 with various artists producing these wonderful pictures. The decision was made to commission a contemplated series of historical Windows, acting both as a history of the English Church and as personal memorials. By adopting your favourite character, event or landscape as shown in the stained glass, you are helping support Worcester Cathedral in keeping its fabric conserved and open for all to see. A £25 example Examples of the types of small decorative panel, there are 13 within each Window. A £50 example Lindisfarne The Armada A £100 example A £200 example St Wulfstan William Caxton Chaucer William Shakespeare Full Catalogue of Cloister Windows Name Location Price Code 13 small decorative pieces East Walk Window 1 £25 CW1 Angel violinist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW2 Angel organist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW3 Angel harpist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW4 Angel singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW5 Benedictine monk writing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW6 Benedictine monk preaching East Walk Window 1 £50 CW7 Benedictine monk singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW8 Benedictine monk East Walk Window 1 £50 CW9 stonemason Angel carrying dates 680-743- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW10 983 Angel carrying dates 1089- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW11 1218 Christ and the Blessed Virgin, East Walk Window 1 £100 CW12 to whom this Cathedral is dedicated St Peter, to whom the first East Walk Window 1 £100 CW13 Cathedral was dedicated St Oswald, bishop 961-992, -

The Castle and the Virgin in Medieval

I 1+ M. Vox THE CASTLE AND THE VIRGIN IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE DRAMA John H. Meagher III A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOWLING GREEN UN1V. LIBRARY 13 © 1977 JOHN HENRY MEAGHER III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 11 ABSTRACT This study examined architectural metaphor and setting in civic pageantry, religious processions, and selected re ligious plays of the middle ages and renaissance. A review of critical works revealed the use of an architectural setting and metaphor in classical Greek literature that continued in Roman and medieval literature. Related examples were the Palace of Venus, the House of Fortune, and the temple or castle of the Virgin. The study then explained the devotion to the Virgin Mother in the middle ages and renaissance. The study showed that two doctrines, the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of Mary, were illustrated in art, literature, and drama, show ing Mary as an active interceding figure. In civic pageantry from 1377 to 1556, the study found that the architectural metaphor and setting was symbolic of a heaven or structure which housed virgins personifying virtues, symbolically protective of royal genealogy. Pro tection of the royal line was associated with Mary, because she was a link in the royal line from David and Solomon to Jesus. As architecture was symbolic in civic pageantry of a protective place for the royal line, so architecture in religious drama was symbolic of, or associated with the Virgin Mother. -

Pierre Riel, the Marquis De Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte's Spanish Policy, 1802-05 Michael W

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Fear and Domination: Pierre Riel, the Marquis de Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte's Spanish Policy, 1802-05 Michael W. Jones Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Fear and Domination: Pierre Riel, the Marquis de Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte’s Spanish Policy, 1802-05 By Michael W. Jones A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2005 Copyright 2004 Michael W. Jones All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approved the dissertation of Michael W. Jones defended on 28 April 2004. ________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Outside Committee Member Patrick O’Sullivan ________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ________________________________ James Jones Committee Member ________________________________ Paul Halpern Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my father Leonard William Jones and my mother Vianne Ruffino Jones. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Earning a Ph.D. has been the most difficult task of my life. It is an endeavor, which involved numerous professors, students, colleagues, friends and family. When I started at Florida State University in August 1994, I had no comprehension of how difficult it would be for everyone involved. Because of the help and kindness of these dear friends and family, I have finally accomplished my dream. -

A Fifteenth-Century Merchant in London and Kent

MA IN HISTORICAL RESEARCH 2014 A FIFTEENTH-CENTURY MERCHANT IN LONDON AND KENT: THOMAS WALSINGHAM (d.1457) Janet Clayton THOMAS WALSINGHAM _______________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS 3 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 4 Chapter 2 THE FAMILY CIRCLE 10 Chapter 3 CITY AND CROWN 22 Chapter 4 LONDON PLACES 31 Chapter 5 KENT LEGACY 40 Chapter 6 CONCLUSION 50 BIBILIOGRAPHY 53 ANNEX 59 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1: The Ballard Mazer (photograph courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, reproduced with the permission of the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College). Figure 2: Thomas Ballard’s seal matrix (photograph courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, reproduced with their permission). Figure 3: Sketch-plan of the City of London showing sites associated with Thomas Walsingham. Figure 4: St Katherine’s Church in 1810 (reproduced from J.B. Nichols, Account of the Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St Katharine near the Tower of London (London, 1824)). Figure 5: Sketch-map of Kent showing sites associated with Thomas Walsingham. Figure 6: Aerial view of Scadbury Park (photograph, Alan Hart). Figure 7: Oyster shells excavated at Scadbury Manor (photograph, Janet Clayton). Figure 8: Surrey white-ware decorated jug excavated at Scadbury (photograph: Alan Hart). Figure 9: Lead token excavated from the moat-wall trench (photograph, Alan Hart). 2 THOMAS WALSINGHAM _______________________________________________________________________________ ABBREVIATIONS Arch Cant Archaeologia Cantiana Bradley H. Bradley, The Views of the Hosts of Alien Merchants 1440-1444 (London, 2011) CCR Calendar of Close Rolls CFR Calendar of Fine Rolls CLB (A-L) R.R. Sharpe (ed.), Calendar of Letter-books preserved among the archives of the Corporation of the City of London at the Guildhall (London, 1899-1912) CPR Calendar of Patent Rolls Hasted E.