Take a Sad Song and Make It Better: an Alternative Reading of Anglo-Indian Stereotypes in Shyamaprasad’S Hey Jude (2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8Th Pune International Film Festival ( 7Th - 14Th January 2010 ) SR

8th Pune International Film Festival ( 7th - 14th January 2010 ) SR. NO. TITLE ORIGINAL TITLE RUNTIME YEAR DIRECTOR COUNTRY OPENING FILM 1 About Elly DARBAREYE ELLY 119 2009 ASGHAR FARHADI IRAN WORLD COMPETITION 1 WHITE LIGHTENIN' - WC WHITE LIGHTNIN' 90 2009 Dominic Murphy UK 2 THE LITTLEONE LA PIVELLINA 100 2009 Tizza Covi, Rainer Frimmel Italy-Austria Alejandro Fernández Almendras - 3 HUACHO - WC HUACHO 89 Chile-France GERMANY CONFIRMED 4 APPLAUSE APPLAUS 86 2009 Martin Zandvliet Denmark CEA MAI FERICITA FATA DIN 5 The happiest girl in the world 100 2009 Radu Jude Romania LUME KIELLETY HEDELMÄ , Dome 6 FORBIDDEN FRUIT -WC 98 2009 Dome Karukoski FINLAND sweden karukoski WHO IS AFRAID OF THE WOLF 7 KDOPAK BY SE VLKA BÁL 90 2008 Maria Procházková czech republic -WC 8 SCRATCH -WC RYSA 89 2009 Michal Rosa poland 9 THE OTHER BANK -WC GAGMA NAPIRI 90 2009 George Ovashvili poland 10 I SAW THE SUN -WC GÜNESI GÖRDÜM 120 2009 Mahsun Kirmizigül. TURKEY THE MAN BEYOND THE BRIDGE- 11 PALTADACHO MUNIS 96 2009 Laxmikant Shetgaonkar INDIA WC 12 FRONTIER BLUES- WC FRONTIER BLUES 95 2009 Babak Jalali Iran-UK-Italy 13 77 DORONSHIP-WC 77 DORONSHIP 90 2009 Pablo Agüero france 14 OPERATION DANUBE-WC OPERACE DUNAJ 104 2009 Jacek Glomb poland 15 THE STRANGER IN ME -WC DAS FREMDE IN MIR 99 2009 Emily Atef GERMANY Marathi competition 1 RITA 145 2009 RENUKA SHAHANE India 2 PAANGIRA 135 2009 RAJEEV PATIL India GOSHTA CHOTI DONGRA 3 GOSHTA CHOTI DONGRA EVDHI 120 2009 NAGESH BHOSALE India EVDHI 4 VIHIR 120 2009 UMESH KULKARNI India 5 A CUP OF TEA EK CUP CHYA 120 -

Vidyamritam Experts

Vidyamritam - Lecture Series The annual extramural series ‘Vidyamritam’ hasbecome popular with its holistic approach for knowledge dissemination through Invited Lectures, Workshops and Conferences. During the Ninth Vidyamritam series, more than 50 lectures and Amrita Film Festivals and many National Conferences and Workshops were conducted. Conferences and Workshops are being organised in Cloud Computing, Cyber Security, Finance and Stock Exchange, FDI, Entrepreneurship, Supply Chain Management, Visual Media and Arts, Video Production, Advertising, Film and Documentary. Vidyamritam Distinguished Visitors Dr. N. Unnikrishnan Nair C. A. Venugopal. C. Govind, F.C.A. Dr. Manohar Shinde Sri. L. Gireesh Kumar Director, Sreepuram Tantric Former Vice Chancellor, CUSAT Mg. Partner, M/s. Varma and Varma Former Professor of Psychiatry Research Centre UCLA, USA Sri. Adarshkumar G. Nair Dr. K. Narayana Moorthy Sri. C. Radhakrishnan Dr. Sarath Menon, Professor MVI, Kochi Project Director, GSLV MK3, ISRO Renowned Literateur University of Houston, USA Dr. A. Unnikrishnan Dr. S. K. Ramachandran Nair Sri. K. Jayakrishnan Sri. K.V. Somanathan Pillai Associate Director, NPOL, Kochi Sr. Medical Administrator, AIMS Director, Xtend Technologies Senior Manager, Indian Bank Dr. N. Gopalakrishnan Dr. K. Ampady, MD, Kerala State Sri. Sunny Joseph Director, Indian Institue of Sri. K.V. PRADEEP KUMAR Scientific Heritage Director (Finance) , Central Ware- Coastal Area Development Corporation Cinematographer housing Corporation, New Delhi Dr. Prem Nair Dr. P. Muralikrishna Sri. G. Jayalal Padma Shri Madhu Medical Director, AIMS Hospital Scientist, NPOL, Kochi Director General, All India Radio Actor 60 Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi - Experts who shared their knowledge Department of Computer Science and I.T. Shri. S. -

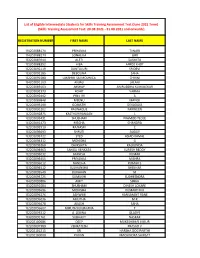

List of Eligible Intermediate Students for Skills Training Assessment Test (June 2021 Term) (Skills Training Assessment Test: 20.08.2021 - 31.08.2021 and Onwards)

List of Eligible Intermediate Students for Skills Training Assessment Test (June 2021 Term) (Skills Training Assessment Test: 20.08.2021 - 31.08.2021 and onwards) REGISTRATION NUMBER FIRST NAME LAST NAME '01202088174 PRIYANKA TIWARI '04202088273 SONALIKA GIRI '03202087644 ALETI SUSMITA '01202088392 HIBA AFROZ KHOT '02202092119 DANTULURI SRIDEVI '03202092185 DEBOLINA SAHA '02202091580 LAKSHMI SAI MOUNICA CHINNI '04202091103 ANJALI LALANI '02202089163 AKSHAY ANIRUDDHA KUWALEKAR '02202092373 ROHIT VARMA '02202092442 PREETHI A '02202089848 MEENU MANOJ '02202093198 GOMATHI DEVADASS '03202091202 RAUNAQUE PARWEEN '02202092875 KASTHURIRANGAN L '01202093431 SHUBHAM PRAMOD YEOLE '03202091473 MEGHA CHANDRA '02202092910 RAJYASRI C '03202095693 SHRUTI AUDDY '03202095722 SYED ASIAD KAMAL '02202094312 MONISHA G '02202095260 DHIKSHITA KALKONDA '02202094963 SANGU VENKATA SURESH REDDY '02202095032 MANISH KUMAR '03202095405 PRIYANKA MISHRA '02202096012 NANDHA KUMAR S '03202094512 SUDHANSHU SHEKHAR '02202095540 BURAHAN M '02202094725 SUMUKHI SUDHEENDRA '04202093886 AMIT SINGH '01202091084 SHUBHAM DINESH LOKARE '02202095696 MONISHA KUMARY M K '01202096276 ASHWINI HANUMANT RANE '02202096036 AMUTHA M R '03202096478 AKASH SAHA '02202096607 MIRUTHYUNJAYANA T '02202093212 A. ZEBINA GLADYS '03202091761 SUBHAJIT NASKAR '01202100686 DEEP MUKESHBHAI JAISUR '02202097389 VENKATESH PRASAD V '02202101215 SRI HARSHA DOGIPARTHI '01202100000 PAVAN MACHINDRA SHIRSAT '01202101675 AARFA HAQUE '02202099058 MANJULA KULLI '02202099128 RAM BABU V '02202100068 VISHNU SURYA PUJARI -

\ HONOURS CONFERRED on MASS COMMUNICATORS Vol. 36 2016

\ HONOURS CONFERRED ON MASS COMMUNICATORS Vol. 36 2016 NO 1 This service is meant primarily for the use of the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting and its media units. This paper gives in brief a background to the National Film Awards as also the details of the 63rd National Film Awards. NATIONAL DOCUMENTATION CENTRE ON MASS COMMUNICATION NEW MEDIA WING (FORMERLY RESEARCH REFERENCE AND TRAINING DIVISION) (MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING) Room No.437-442, Phase IV, Soochana Bhavan, CGO Complex, New Delhi Compiled, Edited & Issued by National Documentation Centre on Mass Communication NEW MEDIA WING (Formerly Research, Reference & Training Division) Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Chief Editor L. R. Vishwanath Editor Alka Mathur NATIONAL FILM AWARDS Recognized as one of the liveliest of arts, cinema is both a means of creative expression and a powerful medium of mass communication. It is a popular means of entertainment as well as an instrument of social change. Realizing its vast potential, the government has been promoting cinema in the country for the past many years. The National Film Awards like various other promotional schemes of the government aim at encouraging the production of quality films. Started on the recommendations of the Film Enquiry Committee, (headed by S.K. Patil in 1954) as an annual incentive, the State Film Awards strive to promote aesthetic and technical standards of films. The nomenclature of the awards was changed to National Film Awards in 1956. The awards have since come a long way to cover the entire spectrum of Indian Cinema. Initially, only three awards were instituted: the President’s Gold medal for the best feature film and the best documentary and the Prime Minister’s Silver Medal for the best Children’s film. -

Prakash Raj INTERNATIONAL PAGES Prakash Raj (Born Prakash Rai; 26 March Prakash to Her Mentor K

MARCH 2018 www.Asia Times.US PAGE 1 www.Asia Times.US Globally Recognized Editor-in-Chief: Azeem A. Quadeer, M.S., P.E. MARCH 2018 Vol 9, Issue 3 FedEx Stubborn about Discounts NRA FedEx Corp. is maintaining discounts for some services at FedEx Office, according members of the National Rifle Associa- to company and NRA websites. NRA of- tion, even as calls for a boycott mount on ficials also didn’t immediately respond to social media after a deadly school shoot- a request for comment. ing in Florida. Delta Air Lines Inc. and United Conti- The courier said it “has never set or nental Holdings Inc. are among compa- changed rates for any of our millions of nies that cut ties with the NRA following customers around the world in response online calls to boycott the gun lobbying to their politics, beliefs or positions on group. Symantec Corp., owner of Lifelock issues.” The NRA is one of hundreds of and Simplisafe Inc.; rental car companies organizations in its alliance programs, Hertz Global Holdings Inc. and Avis Bud- FedEx said Monday in its first public com- get Group Inc. and insurer MetLife Inc. all ment on the matter. have cut ties to the NRA. Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. were among companies Since Sunday, the #BoycottFedEx hashtag being pressured Monday on social media has been included in more than 700 posts to drop the lobbying group’s streaming on Twitter, including one by Marjory TV channel. Stoneman Douglas high school student David Hogg that has been shared more For a look at why Delta, Hertz have more than 13,000 times. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kozhikode City District from 20.01.2019To26.01.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Kozhikode City district from 20.01.2019to26.01.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sajeev Kumar, S/o Velayudhan, Age 52/19, Edavanna 1 (House), Karuvisseri, Vengeri (PO), Kozhikode City 53/2019 U/s Abdul 52, District, Mob: 20-01- 279 IPC 185 Majeed.K, SI BAILED BY Sajeev Kumar Velayudhan Male 9656041477 Karuvisseri 2019, 00:00 MV Act CHEVAYOOR Chevayur PS POLICE Infront of Mathrubhumi 2 Baithul Office, KP 46/2019 U/s 23, Hudha,Modern,Nallal Kesavamenon 20-01- 279 IPC & 185 KOZHIKODE Subash Umer Sharik Nooh Male am Road 2019, 00:50 of MV Act TOWN Chandran, SI ARRESTED Kommadath Parambu, 47/2019 U/s 3 Ahammed 38, Kinassery,Pokkunnu Infront of 20-01- 118(a) of KP KOZHIKODE Subash Salih.A.T Koya Male Post HPO,Kozhikode 2019, 02:10 Act TOWN Chandran, SI ARRESTED 65/2019 U/s 4 27, Chelattu (H), Kallai Eranhipalam 20-01- 118(a) of KP Sajiv,. S, SI of BAILED BY Jishnu C Krishnanunni Male (PO) Jn. 2019, 02:50 Act NADAKKAVU Police POLICE 5 EF-4-5411, Nivedyam, 64/2019 U/s Vivek S Susheel 26, Keshavamenon Nagar Eranhipalam 20-01- 279 IPC & 185 Sajiv,. S, SI of BAILED BY Menon Kumar Male Colony, Eranjipalam Jn. -

12Th IDSFFK Festival Book

FESTIVAL BOOK Organised by Kerala State Chalachitra Academy on behalf of Dept. of Cultural Affairs, Govt. of Kerala CREDITS Chairman & Festival Director: Kamal Vice-Chairperson & Artistic Director: Bina Paul Secretary & Executive Director: Mahesh Panju Treasurer: Santhosh Jacob K Deputy Director (Festival): H Shaji Deputy Director (Programmes): N P Sajeesh Programme Manager (Festival): Gopeekrishna S Programme Manager (Finance): Sajith C C Programme Manager (Programmes): Vimal Kumar V P Print Unit Coordinator: P S Siva Kumar Programme Assistants: Tony Xavier, Saiyed Farooq Festival Assistants: Madhavi Madhupal, Sree Vidya J Cashier: Manu S T Festival Cell: Mary Ninan, Rijoy K J, Sarath M, Abhilash N S, K Harikumar, Shiju Lukose, Jaya L, G Sasikala, K Velayudhan Nair, K John Kurian, Lizy M, Nishanth S T, Shamlal S, Nithin, Abdulla K, Manu Madhavan, Naveen L Johnson, K Venukuttan Nair, Vijayamohan B, K Ravikumar, Arun R, A Maheshkumar Design: Priyaranjanlal FESTIVAL BOOK Chief Editor: Mahesh Panju Executive Editor: H Shaji Associate Editors: Vinayakumar V, Sooraj S Word Processing & Page Setting: Sivaprasad B Academy is grateful to various film journals, festival publications, film festival websites from which we have borrowed content to put together this book. The opinions expressed herein are not necessarily that of the Kerala State Chalachitra Academy or the Editors. Last minute changes to the programme have not been included in this book. Published by: Kerala State Chalachitra Academy, Centre for International Film Research & Archives (CIFRA) (Sathyan Smarakam), Kinfra Film & Video Park, Chanthavila, Kazhakuttom, Sainik School PO, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 585 www.idsffk.in Processed and Printed at: Akshara, Thiruvananthapuram 2 MESSAGE I am very happy to know that the Kerala State Chalachitra Academy is organising the 12th International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala, from 21st to 26th June 2019 at Thiruvananthapuram. -

Portrayal of Subjugated Women in Selected Movies of Shyama Prasad

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.6.Issue 1. 2018 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (Jan-Mar) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE SCREAMING VOICES ON THE SILVER SCREEN: PORTRAYAL OF SUBJUGATED WOMEN IN SELECTED MOVIES OF SHYAMA PRASAD NAMITHA ELIZABETH SMART MA English Language and Literature Kerala, India ABSTRACT Malayalam cinema has always taken its themes from pertinent social issues and has been interwoven with raw material from literature, drama, and politics since its provenience. ’Gender’ is always a very marked term which has a very consequential impact on every practice of a social being as it characterize men and women’s role profoundly. Women are generally considered as housekeeper and their identity depends on this consideration. The main objective of this paper is to study how subjugated women are portrayed in three films of Director Shyamaprasad namely Agnisakshi, Akale and Ore Kadal .These three films show how women are subjugated socially, physically, emotionally and sexually. Agnisakshi is the story of the difficulty of the antharjanam to rise above the fetters of tradition ,a Nampoothiri woman’s struggle to rise above the shackles of tradition and her journey towards self-realization. Akale , is mainly about the timid and fragile Rose, who harbors an inferiority complex because of her deformed legs. Rose’s physical disability not only restrains her physical mobility but also seriously curtails her capacity for involvement in society and wipes out her confidence in her worthiness for another’s love.In Ore Kadal , Deepthi,a village girl whose dream of studying further was not realized by her father and failed to receive the love and care from her husband. -

Malayalam New Film Rating

1 / 5 Malayalam New Film Rating Get updated Latest News and information from Malayalam movie Tamilyogi 2020 Reviews – New Tamil, Malayalam Movies Download .... Know about Film reviews, lead cast & crew, photos & video gallery on ... Daddy Cool Malayalam Movie: Check out the latest news about Mammootty's Daddy .... Mollywood, Malayalam Cinema, Malayalam Movie Reviews, Mohanlal, Mammootty, Dulquer Salmaan, Manju Warrier, Prithviraj, Nivin Pauly, .... 43 avg rating — 254 ratings score: 1,473, and 15 people voted My rating: 2 Ente ... Watch high-quality full songs of all latest movies on Mango Music Malayalam .... Tamilrockers Malayalam, Telugu, Tamil, Kannada Latest Movie Download in HD. ... Kaif starrer have been released and this film is having mixed critics reviews.. 'One' Malayalam movie review: Mammootty's political drama fails to hit the highs · The actor's towering screen presence holds the film together, .... Release Calendar DVD & Blu-ray Releases Top Rated Movies Most ... Get latest Malayalam films ratings, trailers, videos, songs, photos, .... Malayalam, Telugu, Tamil, Movies, Mohanlal, Mammootty, movies, Bollywood, actress, Kannada, download, Film News, malayalam, films, Kerala, Search, Movie Reviews . ... Most South Indian actresses come from the Tamil language film making ... Read latest bollywood news and gossips about your favorite actors and .... Watch new Malayalam video songs, mp4 song videos online for free. Leela Malayalam Movie Online Download - Online. Review and Rating of .... Nizhal Review, mystery thriller,Nizhal malayalam movie ,Nizhal ... The film begins with John Baby suffering an accident, which forces him to ... We do have aggregate rating page for every movies. You can rate and review latest Malayalam movies/films there. Your destination for Every Friday is here. -

An Analysis of the Star Image Construction of Malayalam Actress Sheela

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Research Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies (IRJMS) INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDIES Vol. 2, Issue 9, September, 2016 ISSN (Online): 2454-8499 Impact Factor: 1.3599(GIF), 0.679(IIFS) FEMALE STARDOM: AN ANALYSIS OF THE STAR IMAGE CONSTRUCTION OF MALAYALAM ACTRESS SHEELA 1Ms. SEENA J., 2Dr. D NIVEDHITHA 1Doctoral Research Scholar, 2Associate Professor & Head Department of Electronic Media & Mass Communication Pondicherry University, Pondicherry ABSTRACT: The notion of Stardom in the film field dates back its origin from the Hollywood cinemas and gradually shifted to Bollywood and later to regional cinemas. Star value attracts the financial backing for a movie. Broadly speaking the idea of stardom was predominantly linked to male star. If it comes to female stars the concept of stardom is poles apart. Female stars in the industry were taken granted for the purpose of giving the audience a human sense of beauty and eroticism. This paper is an analysis of the stardom of the yesteryear Malayalam actress Sheela who ruled the Malayalam film industry constantly for 23 years, which is a rare concept in the regional cinema world. She has surpassed the glory of superstardom with 475 films in her credit; a record may be unfeasible for any prevailing actress to outshine. She began her acting career in 1965 and up to 1985 she was active in the limelight of the industry handling strong character roles. After a break of 18 years she returned to celluloid in 2003. Keywords: Charisma, Malayalam Cinema, Sheela, Star image, Star Value, Female Stardom, Male Stardom. -

Film Socialisme, Debuted at Cannes

Kerala State Chalachitra Academy Department of Cultural Affairs Government of Kerala Recognised by Fédération Internationale des Associations de Producteurs de Films International Federation of Film Producers Associations International Film Festival of Kerala FEB. 10 > MARCH 05, 2021 THIRUVANANTHAPURAM KOCHI THALASSERY PALAKKAD The Festival Team Chairman & Festival Director, IFFK: Kamal Vice-Chairperson & Artistic Director, IFFK: Bina Paul Secretary & Executive Director, IFFK: C Ajoy Treasurer: Santhosh Jacob K Deputy Director (Festival): H Shaji Deputy Director (Programmes): N P Sajeesh Programme Manager (Festival): Rijoy K J Programme Manager (Finance): Sajith C C Programme Manager (Programmes): Vimal Kumar V P Festival Assistants: Tony Xavier, Sreevidya J Programme Assistants: Saiyed Farooq Z, Nekha Fathima Sulficar Programme Assistant (Programmes): Nitin R Viswan Print Unit Coordinator: P S Sivakumar Cashier: Manu S T Festival Cell: Mary Ninan, K Harikumar, John Kurian, Madhavi Madhupal, Nishanth S T, Jaya L, G Sasikala, Sarath M, Sandhya B, Abdulla A, Manu M, Shamlal S S, K Venukuttan Nair, Vijayamohan B, Arun R, A Maheshkumar, Lizy M, Omana J, Jayakumari D, Sudharsanan T, Sahadevan R, Rahul Vijayan Festival Programmers: Rosa Carillo, Alessandra Speciale, Eduardo Raccah Signature Film: Mahesh Narayanan Branding design & collaterals: Anoop Ramakrishnan Online Coordination: Shelly J Morris Photo Exhibition: Sajitha Madathil, Hylesh, Nitin R Viswan Filmmakers' Liaison & Guest Relations: Bandhu Prasad Aleyamma, Jayesh LR, Rameez Mohammed, Jithin Mohan AS (Trivi Art Concerns) FESTIVAL BOOK Chief Editor: C Ajoy Executive Editor: Rajesh Chirappadu Associate Editors: Rahul S, Nowfal N Editorial Team: Aneesa Iqbal, N N Baiju, Aswanth Chandrachoodan, Arnold Mathews, Anju S Anand, Swathy Lekshmi Vikram, Akash S S, Jayakumar, Binukumar M R Book Design: Anoop Ramakrishnan Word Processing & Page Setting: Sivaprasad B Academy is grateful to various film journals, festival publications, film festival websites from which we have borrowed content to put together this book. -

Sr.No. PAN Legal Name Trade Name Mobile No Email ID GSTIN 1

Sr.No. PAN Legal Name Trade Name Mobile No Email ID GSTIN 1 AACCS7101B SESA STERLITE LIMITED VEDANTA LIMITED 8128987007 [email protected] 26AACCS7101B1ZY 2 AAACR5055K RELIANCE INDUSTRIES LIMITED RELIANCE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 9974063823 [email protected] 26AAACR5055K1Z9 3 AAACG1840M APAR INDUSTRIES LIMITED APAR INDUSTRIES LTD. 9909027642 [email protected] 26AAACG1840M1ZN 4 AAACH1004N HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED Hindustan Unilever Ltd. 9324843805 [email protected] 26AAACH1004N1ZW 5 AAACC4481E CASTROL INDIA LIMITED CASTROL INDIA LTD. 9167790529 [email protected] 26AAACC4481E1ZX 6 AABCJ5937F JSK INDUSTRIES PRIVATE LIMITED JSK INDUSTRIES PVT. LTD 8511186620 [email protected] 26AABCJ5937F1ZK 7 AAVCS7209P STERLITE POWER TRANSMISSION LIMITED STERLITE POWER TRANSMISSION LIMITED 7506779953 [email protected] 26AAVCS7209P2ZC 8 AAACS7934A SAVITA OIL TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED SAVITA OIL TECHNOLOGIES LTD. 7738461666 [email protected] 26AAACS7934A1ZL 9 AACCH0941E GULF OIL LUBRICANTS INDIA LIMITED GULF OIL LUBRICANTS INDIA LIMITED 9904103528 [email protected] 26AACCH0941E1Z1 10 AAACJ0866E JOHNSON & JOHNSON LIMITED JOHNSON AND JOHNSON LIMITED 9821333187 [email protected] 26AAACJ0866E1ZT 11 AADCD5709P D N H SPINNERS PRIVATE LIMITED DNH SPINNERS PVT LTD 9824131928 [email protected] 26AADCD5709P1Z9 12 AALCS2136B STANDARD GREASES AND SPECIALITIES PRIVATE LIMITED STANDARD GREASES AND SPECIALITES PVT. LTD. 9879002438 [email protected] 26AALCS2136B1ZO 13 AAACK1314Q KLJ POLYMERS AND CHEMICALS LTD KLJ POLYMERS AND CHEMICALS LTD. UNIT-II 9998966117 [email protected] 26AAACK1314Q1ZI 14 AACCS4923P RAJ PETRO SPECIALITIES PRIVATE LIMITED RAJ PETRO SPECIALITIES PVT. LTD. 8141800531 [email protected] 26AACCS4923P1ZX 15 AAACI1220M IPCA LABORATORIES LIMITED IPCA LABORATORIES LTD. 9324275115 [email protected] 26AAACI1220M1ZV 16 AAACN2329N NILKAMAL LIMITED NILKAMAL LTD. 7045883964 [email protected] 26AAACN2329N1ZC 17 AGLPS5447A NITIN SHANTARAM SULE HINDALCO INDUSTRIES LTD.