Oil and Insurgency in the Niger Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This PDF File

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.10, No.3, 2020 Primordial Niger Delta, Petroleum Development in Nigeria and the Niger Delta Development Commission Act: A Food For Thought! Edward T. Bristol-Alagbariya* Associate Dean & Senior Multidisciplinary Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Port Harcourt, NIGERIA; Affiliate Visiting Fellow, University of Aberdeen, UNITED KINGDOM; and Visiting Research Fellow, Centre for Energy, Petroleum & Mineral Law and Policy (CEPMLP), Graduate School of Natural Resources Law, Policy & Management, University of Dundee, Scotland, UNITED KINGDOM * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The historic and geographic ethnic minority Delta region of Nigeria, which may be called the Nigerian Delta region or the Niger Delta region, has been in existence from time immemorial, as other primordial ethnic nationality areas and regions, which were in existence centuries before the birth of modern Nigeria. In the early times, the people of the Niger Delta region established foreign relations between and among themselves, as people of immediate neigbouring primordial areas or tribes. They also established long-distance foreign relations with distant tribes that became parts and parcels of modern Nigeria. The Niger Delta region, known as the Southern Minorities area of Nigeria as well as the South-South geo-political zone of Nigeria, is the primordial and true Delta region of Nigeria. The region occupies a very strategic geographic location between Nigeria and the rest of the world. For example, with regard to trade, politics and foreign relations, the Nigerian Delta region has been strategic throughout history, ranging, for instance, from the era of the Atlantic trade to the ongoing era of petroleum resources development in Nigeria. -

Nigeria Last Updated: May 6, 2016

Country Analysis Brief: Nigeria Last Updated: May 6, 2016 Overview Nigeria is currently the largest oil producer in Africa and was the world's fourth-largest exporter of LNG in 2015. Nigeria’s oil production is hampered by instability and supply disruptions, while its natural gas sector is restricted by the lack of infrastructure to commercialize natural gas that is currently flared (burned off). Nigeria is the largest oil producer in Africa, holds the largest natural gas reserves on the continent, and was the world’s fourth-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in 2015.1 Nigeria became a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1971, more than a decade after oil production began in the oil-rich Bayelsa State in the 1950s.2 Although Nigeria is the leading oil producer in Africa, production is affected by sporadic supply disruptions, which have resulted in unplanned outages of up to 500,000 barrels per day (b/d). Figure 1: Map of Nigeria Source: U.S. Department of State 1 Nigeria’s oil and natural gas industry is primarily located in the southern Niger Delta area, where it has been a source of conflict. Local groups seeking a share of the wealth often attack the oil infrastructure, forcing companies to declare force majeure on oil shipments (a legal clause that allows a party to not satisfy contractual agreements because of circumstances beyond their control). At the same time, oil theft leads to pipeline damage that is often severe, causing loss of production, pollution, and forcing companies to shut in production. -

Dr. Modupe Oshikoya, Department of Political Science, Virginia Wesleyan University – Written Evidence (ZAF0056)

Dr. Modupe Oshikoya, Department of Political Science, Virginia Wesleyan University – Written evidence (ZAF0056) 1. What are the major security challenges facing Nigeria, and how effectively is the Nigerian government addressing them? 1.1 Boko Haram The insurgency group known globally as Boko Haram continues to wreak havoc in northeast Nigeria and the countries bordering Lake Chad – Cameroon, Chad and Niger. The sect refers to itself as Jamā'at Ahl as- Sunnah lid-Da'wah wa'l-Jihād [JAS], which in Arabic means ‘People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teaching and Jihad’, and rejects all Western beliefs. Their doctrine embraced the strict adherence to Islam through the establishment of sharia law across all of Nigeria, by directly attacking government and military targets.1 However, under their new leader, Abubakar Shekau, the group transformed in 2009 into a more radical Salafist Islamist group. They increased the number of violent and brutal incursions onto the civilian population, mosques, churches, and hospitals, using suicide bombers and improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The most prominent attack occurred in a suicide car bomb at the UN headquarters in Abuja in August 2011.2 Through the use of guerrilla tactics, Boko Haram’s quest for a caliphate led them to capture swathes of territory in the northeast of the country in 2014, where they indiscriminately killed men, women and children. One of the worst massacres occurred in Borno state in the town of Baga, where nearly an estimated 2,000 people were killed in a few hours.3 This radicalized ideological rhetoric of the group was underscored by their pledge allegiance to Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) in March 2015, leading them rename themselves as Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP).4 One of the most troubling characteristics of the insurgency has been the resultant sexual violence and exploitation of the civilian population. -

Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Quarterly Report Second Quarter – January 1 to March 31, 2019

d Northern Education Initiative Plus PY4 Quarterly Report Second Quarter – January 1 to March 31, 2019 DISCLAIMER This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Creative Associates International. Submission Date: April 30, 2019 Contract Number: AID-620-C-15-00002 October 26, 2015 – October 25, 2020 COR: Olawale Samuel Submitted by: Nurudeen Lawal, Acting Chief of Party, Northern Education Initiative Plus 38 Mike Akhigbe Street, Jabi, Abuja, Nigeria Email: [email protected] Northern Education Initiative Plus - PY4 Quarter 2 Report iii CONTENT 1. PROGRAM OVERVIEW ................................................................................................... 5 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. 6 1.1 Program Description ...................................................................................... 8 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ 12 2.1 Implementation Status ................................................................................. 15 Intermediate Result 1. Government systems strengthened to increase the number of students enrolled in appropriate, relevant, approved educational options, especially girls and out-of-school children (OOSC) in target locations ............................................................................. 15 Sub IR 1.1 Increased number of educational options (formal, NFLC) meeting -

Africa's Oil & Gas Scene After the Boom

January 2019: ISSUE 117 Africa’s oil and gas scene has This issue of the Oxford Energy Forum AFRICA'S OIL & GAS undergone dramatic changes over explores the aftermath of Africa’s SCENE AFTER THE BOOM: the past two decades. In 2000, the energy boom. It draws on contributors continent was producing nearly 8 from industry, academia, and civil WHAT LIES AHEAD million barrels per day (b/d). A society to offer multiple views of the decade later, largely on the back of opportunities and challenges that lie new production from Angola and ahead for oil and gas development on Contents Sudan, output rose to above 10 the African continent. The issue Introduction 1 million b/d. This came at the same examines continuities and changes in Luke Patey & Ricardo Soares de Oliveira time as a sharp rise in global oil the African energy landscape since oil Prospects for African oil 4 prices, generating enormous prices fell from record highs after 2014. James McCullagh and Virendra Chauhan revenues for African oil producers It focuses on the politics and The political economy of decline in Nigeria and Angola 6 and setting off exploration activities economics of seasoned producers in Ricardo Soares de Oliveira in largely unexplored regions. As sub-Saharan Africa and the birth of new Angola after Dos Santos 8 prices rose to over $100 per barrel oil and gas producers and up-and- Lucy Corkin on average from 2010 to 2014, comers, and shows that while old Nigeria’s oil reforms in limbo 10 Africa enjoyed an unprecedented oil political and security challenges persist, Eklavya Gupte boom. -

Federal Republic of Nigeria .Official Gazette

Extraordinary Federal Republic of Nigeria .Official Gazette No. 40 Lagos - 3rd May, 2011 Vol. 98 J Government Notice No. 126 The followingis published as Supplement to this Gazette: S.I No. Short Title Page 13 National Environmental (DesertificationControl and Drought Mitigation ) Regulations, 2011 .. B399 -417 Printed and Published by The Federal GovernmentPrinter, Abuja, Nigeria FGP72/7201 l/400(OL 35) Annual subscription from 1st January, 2011 is Local: N 15,000.00 Overseas: N 21,500.00 (Surface Mail] N24.500.00 [Second Class Air Mail). Present issue Nl,500.00 per copy. Subscriberswho wish to obtain Gazetteafter 1st Januaryshould apply to the Federal Government Printer, Lagos for amended Subscriptions. B399 NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL (DESERTIFICATION CONTROL AND DROUGHT MITIGATION) REGULATIONS, 2011 ARRANGEMENT OF REGULA TI ONS REGULATION: PART I-GENERAL PROVISIONS ON DESERTIFICATION CONTROL 1. Application. 2. Objectives. 3. Principles. PART II -REGULATI ONS ON DESERTIFICATION CONTROL 4. Duties of the Agency. 5. The Role of States and Local Governments. 'i 6. Declaration of Specially ProtectedAreas. 7. DesertificationControl Guidelines. 8. Permit. 9. Implied Covenants. 10. Duties of Land Owners and Users. PART III - GENERAL PROVISIONS ON DROUGHT MITIGATION 11. Application. 12. Objectives. 13. Principles. PART IV -REGULATIONS ON DROUGHT MITIGATION 14. Duties of the Agency. 15. Duties of Relevant Line Ministries, Departments and Agencies. 16. Duties of the State Enforcement Team. 17. Duties of the Local Government EnforcementTeam. 18. Drought Mitigation Guidelines. 19. Health and Nutrition. / 20. Prevention of Wildfire. PART V - GENERAL 21. Offence and Penalties. 22. Interpretations. 23. Citation. B400 PART VJ - SCHEDULES Schedule - I List of Frontline States/Desertification Prone Areas in Nigeria. -

Reflections on Alagbariya, Asimini and Halliday-Awusa As Selfless

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.10, No.3, 2020 Natural Law as Bedrock of Good Governance: Reflections on Alagbariya, Asimini and Halliday-Awusa as Selfless Monarchs towards Good Traditional Governance and Sustainable Community Development in Oil-rich Bonny Kingdom Edward T. Bristol-Alagbariya * Associate Dean & Senior Multidisciplinary Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Port Harcourt, NIGERIA; Affiliate Visiting Fellow, University of Aberdeen, UNITED KINGDOM; and Visiting Research Fellow, Centre for Energy, Petroleum & Mineral Law and Policy (CEPMLP), Graduate School of Natural Resources Law, Policy & Management, University of Dundee, Scotland, UNITED KINGDOM * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Oil-rich Ancient Grand Bonny Kingdom, founded before or about 1,000AD, was the economic and political centre of the Ancient Niger Delta region and a significant symbol of African civilisation, before the creation of Opobo Kingdom out of it (in 1870) and the eventual evolution of modern Nigeria (in 1914). The people and houses of this oil-rich Kingdom of the Nigerian Delta region invest more in traditional rulership, based on house system of governance. The people rely more on their traditional rulers to foster their livelihoods and cater for their wellbeing and the overall good and prosperity of the Kingdom. Hence, there is a need for good traditional governance (GTG), more so, when the foundations of GTG and its characteristic features, based on natural law and natural rights, were firmly established during the era of the Kingdom’s Premier Monarchs (Ndoli-Okpara, Opuamakuba, Alagbariya and Asimini), up to the reign of King Halliday-Awusa. -

First Election Security Threat Assessment

SECURITY THREAT ASSESSMENT: TOWARDS 2015 ELECTIONS January – June 2013 edition With Support from the MacArthur Foundation Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Security Threat Assessment for North Central III. Security Threat Assessment for North East IV. Security Threat Assessment for North West V. Security Threat Assessment for South East VI. Security Threat Assessment for South South VII. Security Threat Assessment for South West Executive Summary Political Context The merger between the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), All Nigerian Peoples Party (ANPP) and other smaller parties, has provided an opportunity for opposition parties to align and challenge the dominance of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). This however will also provide the backdrop for a keenly contested election in 2015. The zoning arrangement for the presidency is also a key issue that will define the face of the 2015 elections and possible security consequences. Across the six geopolitical zones, other factors will define the elections. These include the persisting state of insecurity from the insurgency and activities of militants and vigilante groups, the high stakes of election as a result of the availability of derivation revenues, the ethnic heterogeneity that makes elite consensus more difficult to attain, as well as the difficult environmental terrain that makes policing of elections a herculean task. Preparations for the Elections The political temperature across the country is heating up in preparation for the 2015 elections. While some state governors are up for re-election, most others are serving out their second terms. The implication is that most of the states are open for grab by either of the major parties and will therefore make the electoral contest fiercer in 2015 both within the political parties and in the general election. -

AFRREV VOL 13 (4), S/NO 56, SEPTEMBER, 2019 African Research Review: an International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia AFRREV Vol

AFRREV VOL 13 (4), S/NO 56, SEPTEMBER, 2019 African Research Review: An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia AFRREV Vol. 13 (4), Serial No 56, September, 2019: 74-85 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v13i4.7 Chieftaincy Institution and Military Formations in the Eastern Niger Delta of Nigeria Adagogo-Brown, Edna, PhD. Associate Professor of History Captain Elechi Amadi Polytechnic E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +2348033091227 Abstract This paper showed the military formations in the Eastern Niger Delta prior to Nigerian independence which the British colonial government tried to destroy in the wake of the establishment of the Protectorate of the Oil Rivers and Consular paper treaties. The Chieftaincy institution in the Eastern Niger Delta dates to at least 1000 years ago. After the migration story had been completed, the various communities that made up the Eastern Niger Delta commenced the early political and economic institutions with the ward or wari system of government and the long-distance trade with their neighbours. In the early fifteenth century, the Asimini ward in Bonny and Korome ward in Kalabari produced their early kings. The Chieftaincy institution assumed a greater relevance in the kingdoms of Bonny and Kalabari with the emergence of King Perekule of Bonny and King Amachree of Kalabari respectively. These two kings introduced the war canoe house political system in response to the slave trade which had increased tremendously with the entrance of Britain. The risks and the competitions among the City-states of Bonny, Kalabari, Okrika and Nembe-Brass to procure slaves necessitated the acquisition of war canoes to equip and constitute the military arm of the states. -

Nigeria: the Challenge of Military Reform

Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform Africa Report N°237 | 6 June 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Long Decline .............................................................................................................. 3 A. The Legacy of Military Rule ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Military under Democracy: Failed Promises of Reform .................................... 4 1. The Obasanjo years .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Yar’Adua and Jonathan years ....................................................................... 7 3. The military’s self-driven attempts at reform ...................................................... 8 III. Dimensions of Distress ..................................................................................................... 9 A. The Problems of Leadership and Civilian Oversight ................................................ -

Ethnic Militias and Conflict in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: the International Dimensions (1999-2009)

ETHNIC MILITIAS AND CONFLICT IN THE NIGER DELTA REGION OF NIGERIA: THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS (1999-2009) By Lysias Dodd Gilbert A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ADEKUNLE AMUWO 2010 DECLARATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Graduate Programme in Political Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work. All citations, references and borrowed ideas have been duly acknowledged. I confirm that an external editor was not used. It is being submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities, Development and Social Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. None of the present work has been submitted previously for any degree or examination in any other University. ______________________________________ Lysias Dodd Gilbert ______________________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page...................................................................................................................................i Certification...............................................................................................................................ii Table of Contents.....................................................................................................................iii Dedication................................................................................................................................vii -

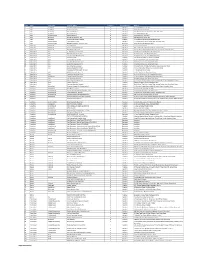

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State.