The Silk Loom Community in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tezpur University Is Ranked Fifth in the National Institutional Ranking Fram

Volume No. 9 : : Issue 1 : : May 2016 In this issue Tezpur University receives the Visitor’s Best University Award 2016 2 VC’s Corner 3 Awards and Achievements 5 Seminars / Conferences / Events 10 Select Publications 16 Select Projects 17 Students’ Achievements 18 University Events 20 New Joining The NIRF top 10 universities are: 1. Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, Karnataka (91.81) 2. Institute of Chemical Technology, Mumbai, Maharashtra (87.58) 3. Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, Delhi (86.45) 4. University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, Telengana (85.45) 5. Tezpur University, Tezpur, Assam (84.31) 6. University of Delhi, Delhi (83.19) 7. Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh (81.22) 8. Indian Institute of Space Science & Tezpur University is ranked fifth in the National Technology, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) 2016 (78.82) 9. Birla Institute of Technology & Science, among the top 100 universities in India Pilani, Rajasthan (76.85) 10. Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (76.62) 2 Volume No. 9 : : Issue 1 : : May 2016 From the Vice Chancellor I am really very sorry to confess to a lapse on our part which the performance of a university might be for not being able to publish the Newsletter for nearly judged. The assessment is made by others including a year. We shall certainly like to see no recurrence of peers. To this end, our University has earned some such a slip in future. humble recognition by way of receiving the Visitor’s Best University Award 2016, 5th position in the NIRF The period of last 10 to 12 months has been remarka- MHRD Rankings 2016, NBA Accreditation and the bly eventful for our University. -

Brahmaputra and the Socio-Economic Life of People of Assam

Brahmaputra and the Socio-Economic Life of People of Assam Authors Dr. Purusottam Nayak Professor of Economics North-Eastern Hill University Shillong, Meghalaya, PIN – 793 022 Email: [email protected] Phone: +91-9436111308 & Dr. Bhagirathi Panda Professor of Economics North-Eastern Hill University Shillong, Meghalaya, PIN – 793 022 Email: [email protected] Phone: +91-9436117613 CONTENTS 1. Introduction and the Need for the Study 1.1 Objectives of the Study 1.2 Methodology and Data Sources 2. Assam and Its Economy 2.1 Socio-Demographic Features 2.2 Economic Features 3. The River Brahmaputra 4. Literature Review 5. Findings Based on Secondary Data 5.1 Positive Impact on Livelihood 5.2 Positive Impact on Infrastructure 5.2.1 Water Transport 5.2.2 Power 5.3 Tourism 5.4 Fishery 5.5 Negative Impact on Livelihood and Infrastructure 5.6 The Economy of Char Areas 5.6.1 Demographic Profile of Char Areas 5.6.2 Vicious Circle of Poverty in Char Areas 6. Micro Situation through Case Studies of Regions and Individuals 6.1 Majuli 6.1.1 A Case Study of Majuli River Island 6.1.2 Individual Case Studies in Majuli 6.1.3 Lessons from the Cases from Majuli 6.1.4 Economics of Ferry Business in Majuli Ghats 6.2 Dhubri 6.2.1 A Case Study of Dhubri 6.2.2 Individual Case Studies in Dhubri 6.2.3 Lessons from the Cases in Dhubri 6.3 Guwahati 6.3.1 A Case of Rani Chapari Island 6.3.2 Individual Case Study in Bhattapara 7. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

History Bodo-Bhutia Border Trade Relations in Colonial Era ABSTRACT

Volume : 5 | Issue : 5 | May 2016 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 | IF : 3.508 | IC Value : 69.48 Research Paper History Bodo-Bhutia Border Trade Relations In KEYWORDS : Border trade, Bodos, Bhut- Colonial Era ias, Economy Asha Basumatary Assistant Professor, Department of History Cachar College, Silchar P.O. Silchar, 788001 ABSTRACT Border trade is an overland trade operated by the way of exchange of certain commodities by the people living along both sides of the international border. It differs from trade carried through air, land and sea ports. Since North- Eastern states of India shares land borders with the countries of Bhutan, Tibet, China, Bangladesh, Myanmar, the Bodo tribes inhabiting the northern foothill regions of Assam and Bengal have maintained border trade relations with the Bhutia (Bhootea) tribes of Bhutan hills and the western Arunachal Pradesh hills since long time. Through the hill tribes, their trade was further extended to the Tibetans and the Chinese traders. This article thus intends to explore how Bodo tribes carried out border trade with Bhutia tribes of Bhutan during colonial times, and also to examine how far it contributed to the growth of their economy. Introduction cially representing the increase in trade in certain areas or re- Assam is the homeland of numerous indigenous tribes came gions, whereas the crossing borders are comparatively easy and from different directions for ages. It had once been a melting the products are much cheaper in one place than the other. In pot of which the different tribes took shelter with their different case of trade existed in between the Bodos and Bhutias some lo- multihued culture and traditions professing different religious cally produced commodities were traded by way of exchange in beliefs and practices. -

Assam and Attached 80180 to the Occupation of Pat Learing by Which They Lived

THE SILK INDUSTRY OP •• .ASSAM BY RA! BHUPAL CHANDRA BASU BAHADUR, B.A.., lI.B.A..C.,lI.B.U. (EIIG.) EXTRA ASSISfANf COMMISSIONER ON SPEOIAL DUTY. BHILLONG: l'BINTE:Q A~ THE ~~AH 8EORETARIA~ l'RI~TING OFFICE. 1915.- CONTENTS. l'agt. Chapter I.-General ... ... ... .n n.-The rearing of the eri silkworm ... ... '1-16 " •• fIIullI 17-29 " III.-The rearing of the silkworm ... ... .. lV.-The rearing of the ,,,,, eilkworm ... .. SO-38 " V.-The Reeling and Spinning of Silk ... ... 39-46 47-52 " VL-The Preparation of yarn for weaving ... ... VlI.-Final 5S-57 " ... ... ... ... Appendix l.-Statemen~ of diseases fonnd in specimens of silkworms 58-59 1I(1J}.-Expori. of silk hy rail and river 60 " ... ... II(~}.-Imports of silk hy rail and river 61 " ... ... .. lI(c).-Exports of ,ilk to Bhutan' and other tmna·frontier countriel ••• . ... 62 lIl.-Estimated Dumher of mulberry silkworm rearers ... 63-640 " \ .. lV.-Note ou Synthetic Dyes used at PUIIl for dyeing eri silk ••• '... ... ,i. 65-66 " V.-Note OD Gr8/lieria diselSe of the fIII'11I silkworm ... 61-68 THE SILK INDUSTRY OF ASSAM. ---- CHAPTER I • • •• GENERAL. Out of the four speoies of silkworms reared in India, three are cultivated in Assam, namely, the cOlDmon or mulber'l: silkworm, the 'Three ...rie~i.1 of Silld" A....... mu!!a and the eri. The fourth, ./flsser, is not reared ill Assam at the present day, tho11gh it occurs in the wild state.. Er; and muga silk .re known to the outside world under tbe name of Assam silk. Mulberry silk which is known in Assa.m as pat is grown to such a small extent that the fa.ct of its existence in this province is not generally known. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

List of Candidates Called for Preliminary Examination for Direct Recruitment of Grade-Iii Officers in Assam Judicial Service

LIST OF CANDIDATES CALLED FOR PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION FOR DIRECT RECRUITMENT OF GRADE-III OFFICERS IN ASSAM JUDICIAL SERVICE. Sl No Name of the Category Roll No Present Address Candidate 1 2 3 4 5 1 A.M. MUKHTAR AHMED General 0001 C/O Imran Hussain (S.I. of Ploice), Convoy Road, Near Radio Station, P.O.- CHOUDHURY Boiragimath, Dist.- Dibrugarh, Pin-786003, Assam 2 AAM MOK KHENLOUNG ST 0002 Tipam Phakey Village, P.O.- Tipam(Joypur), Dist.- Dibrugarh(Assam), Pin- 786614 3 ABBAS ALI DEWAN General 0003 Vill: Dewrikuchi, P.O.:-Sonkuchi, P.S.& Dist.:- Barpeta, Assam, Pin-781314 4 ABDIDAR HUSSAIN OBC 0004 C/O Abdul Motin, Moirabari Sr. Madrassa, Vill, PO & PS-Moirabari, Dist-Morigaon SIDDIQUEE (Assam), Pin-782126 5 ABDUL ASAD REZAUL General 0005 C/O Pradip Sarkar, Debdaru Path, H/No.19, Dispur, Ghy-6. KARIM 6 ABDUL AZIM BARBHUIYA General 0006 Vill-Borbond Part-III, PO-Baliura, PS & Dist-Hailakandi (Assam) 7 ABDUL AZIZ General 0007 Vill. Piradhara Part - I, P.O. Piradhara, Dist. Bongaigaon, Assam, Pin - 783384. 8 ABDUL AZIZ General 0008 ISLAMPUR, RANGIA,WARD NO2, P.O.-RANGIA, DIST.- KAMRUP, PIN-781365 9 ABDUL BARIK General 0009 F. Ali Ahmed Nagar, Panjabari, Road, Sewali Path, Bye Lane - 5, House No.10, Guwahati - 781037. 10 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0010 Vill: Chamaria Pam, P.O. Mahtoli, P.S. Boko, Dist. Kamrup(R), Assam, Pin:-781136 11 ABDUL BATEN ACONDA General 0011 Vill: Pub- Mahachara, P.O. & P.S. -Kachumara, Dist. Barpeta, Assam, Pin. 781127 12 ABDUL BATEN SK. General 0012 Vill-Char-Katdanga Pt-I, PO-Mohurirchar, PS-South Salmara, Dist-Dhubri (Assam) 13 ABDUL GAFFAR General 0013 C/O AKHTAR PARVEZ, ADVOCATE, HOUSE NO. -

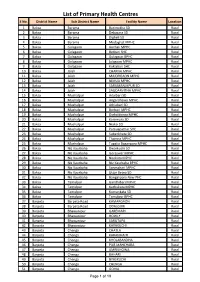

List of Primary Health Centres S No

List of Primary Health Centres S No. District Name Sub District Name Facility Name Location 1 Baksa Barama Barimakha SD Rural 2 Baksa Barama Debasara SD Rural 3 Baksa Barama Digheli SD Rural 4 Baksa Barama Medaghat MPHC Rural 5 Baksa Golagaon Anchali MPHC Rural 6 Baksa Golagaon Betbari SHC Rural 7 Baksa Golagaon Golagaon BPHC Rural 8 Baksa Golagaon Jalagaon MPHC Rural 9 Baksa Golagaon Koklabari SHC Rural 10 Baksa Jalah CHARNA MPHC Rural 11 Baksa Jalah MAJORGAON MPHC Rural 12 Baksa Jalah NIMUA MPHC Rural 13 Baksa Jalah SARUMANLKPUR SD Rural 14 Baksa Jalah SAUDARVITHA MPHC Rural 15 Baksa Mushalpur Adalbari SD Rural 16 Baksa Mushalpur Angardhawa MPHC Rural 17 Baksa Mushalpur Athiabari SD Rural 18 Baksa Mushalpur Borbori MPHC Rural 19 Baksa Mushalpur Dighaldonga MPHC Rural 20 Baksa Mushalpur Karemura SD Rural 21 Baksa Mushalpur Niaksi SD Rural 22 Baksa Mushalpur Pamuapathar SHC Rural 23 Baksa Mushalpur Subankhata SD Rural 24 Baksa Mushalpur Thamna MPHC Rural 25 Baksa Mushalpur Tupalia Baganpara MPHC Rural 26 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Dwarkuchi SD Rural 27 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Goreswar MPHC Rural 28 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Naokata MPHC Rural 29 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Niz Kaurbaha BPHC Rural 30 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Sonmahari MPHC Rural 31 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Uttar Betna SD Rural 32 Baksa Niz Kaurbaha Bangalipara New PHC Rural 33 Baksa Tamulpur Gandhibari MPHC Rural 34 Baksa Tamulpur Kachukata MPHC Rural 35 Baksa Tamulpur Kumarikata SD Rural 36 Baksa Tamulpur Tamulpur BPHC Rural 37 Barpeta Barpeta Road KAMARGAON Rural 38 Barpeta Barpeta Road ODALGURI Rural 39 Barpeta -

Assam Power Sector Investment Program - Tranche 2

Environmental Monitoring Report Project Number: 47101-003 March 2019 Period: January 2018 – June 2018 IND: Assam Power Sector Investment Program - Tranche 2 Submitted by Assam Power Distribution Company Limited, Guwahati This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Assam Power Sector Investment Program Tranche – 2 (Loan No.: 3327-IND) Bi-Annual Environmental Safeguard Monitoring Report (January-June 2018) February 2019 Prepared by the Assam Power Distribution Company Limited for the Asian Development Bank This environmental safeguard monitoring report is a document of the borrower and made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy 2011 and the Safeguard Policy Statement 2009. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff. Assam Power Sector Investment Program, Tranche - 2 Loan No. IND-3327 Abbreviation ADB Asian Development Bank AEGCL Assam Electricity Grid Corporation Ltd. AP Affected People APSEIP Assam Power Sector Enhancement Investment Program ASEB Assam State Electricity Board D.C. District Collector EA Executing Agency EMP Environmental Management Plan ESMU Environmental and Social Management Unit GoA Government of Assam GoI Government of India GRC Grievance Redress Committee GWSP Guwahati Water Supply Project IA Implementing Agency IEE Initial Environmental Examination Ltd. -

Town Directory, Part IX-A, Series-4, Assam

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES-4 ASSAM PART IX-A TOWN· DIRECTORY .Director of Census Operations, Assam Registrar Genera. of India (In charge of the census of India and vital statistics) Office Address: 2A Mansingh Road New Delhi 110011, India Telephone: (91-11 )3383761 Fax: (91-11)3383145 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.censusindia.net Registrar General of India's publications can be purchased from the following: • The Sales Depot (Phone:338 6583) Office of the Registrar General of India 2-A Mansingh Road New Delhi 110011, India Directorates of Census Operations in the capitals of all states and union territories in India • The Controller of Publication Old Secretariat Civil Lines \ Delhi 110054 • .~Itab Mahal ~ te Emporia Complex. Unit No.21 Be. ba Kharak Singh Marg Ne\~ Delht110 001 • sale!.\ outlets of the Controller of Publication all over India Census data ,'wailable on floppy disks can be purcha~'~d from the following: • Office of live Registrar General. India Data Proce'ssing Division 2nd Floor, .~. Wing Pushpa Bhav."an Madangir Roatj New Delhi 110 i.162, India Telephone: (91-1'1)6H81558 Fax: (91-11)6S180295 Email: [email protected] © Registrar General of India The contents of this pul)lication may be quoted citing the sou rce clearly CONTENTS Page No. FOREWORD (v) PREFACE {vii) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT (be) LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS (xi) SECTION-A 1-48 Analytical Note Chapter-I Introduction 5 Chapter-II Status and Growth History 7. Chapter-III Physical and Locational Aspect 15 Chapter-IV Municipal Finance 21 Chapter-V Civic -

Pat-Muga Industry As a Source of Women Empowerment in Rural Areas of Kamrup District of Assam

RESEARCH PAPER Economics Volume : 5 | Issue : 10 | October 2015 | ISSN - 2249-555X Pat-Muga Industry as a Source of Women Empowerment in Rural Areas of Kamrup District of Assam KEYWORDS Women Empowerment, Employment, weaver Preeti Chakravartty Research Scholar Department of Economics Bodoland University, Kokrajhar ABSTRACT Women Empowerment refers to increasing the economic, political, social, educational, gender or spir- itual strength of women. It often involves the empowered developing confidence in their own capacities. Here, an attempt has been made to analyse the nature of women empowerment through Pat-Muga industry. Pat-Muga industry is one of the oldest weaving industries in Assam. Females known as born weaver in North-East India. The paper is mainly based on to discuss the employment opportunities of women in Pat-Muga silk sector, present mar- ket situation and will discuss the various problems faced by the women this industry. The paper is an empirical study made in Sualkuchi village of Assam, based on both Primary and Secondary data collection. Introduction: There are four different varieties of silk- Muga, Eri, Mulber- The word women empowerment essentially means that ry and Tasar silk. India is the second largest producer of the women should have the power or capacity to regulate silk followed by China. India contributes 18% of total raw their day-to-day lives in the social, political and economic silk of the world. terms – a power which enables them to move from the pe- riphery to the centre stage. Women Empowerment refers Assam has the unique distinction in producing four major to empowering women to be self-dependent by providing varieties of silk- Muga silk, Eri silk, Mulberry silk and Tasar them access to all the freedoms and opportunities, which silk. -

Ancient Indian Texts of Knowledge and Wisdom

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com The Saree - The Very Essence of Indian Womanhood Copyright © 2013, DollsofIndia A saree or sari is a long strip of unstitched cloth, which is draped by Indian women – it practically typifies Indian women and showcases the vast diversity of Indian culture as a whole. The word "Sari" is derived from the Sanskrit and the Prakrit (pre-Sanskrit language) root, "Sati", which means, "strip of fabric". Interestingly, the Buddhist Jain works, the Jatakas, describe women’s apparel, called the "Sattika", which could well have been similar to the present-day saree. Another fact is that the end of the saree that hangs downward from the shoulder is called the Pallav. Experts believe that the name came to be during the reign of the Pallavas, the ruling dynasty of ancient Tamilnadu. A saree typically ranges from six to nine yards in length and can be worn in several ways, depending upon the native of the wearer and her outlook on current fashion. Usually, a saree is tucked in at the waist and is then wrapped around the body with pleats in the center, the other end draped loosely over the left shoulder, showing the midriff. This apparel is also popular in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Singapore and Malaysia. This very feminine garment is worn over a petticoat, also referred to as a lehenga in the North, a paavaadai in the South, a parkar or ghaghra in the West and a shaya in the East. It is worn along with a bodice or blouse, called the choli (in North India) or ravikkai (in South India).