A. Study of Clay Handles on Ceramic Vessel Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leeds Pottery

Leeds Art Library Research Guide Leeds Pottery Our Art Research Guides list some of the most unique and interesting items at Leeds Central Library, including items from our Special Collections, reference materials and books available for loan. Other items are listed in our online catalogues. Call: 0113 378 7017 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.leeds.gov.uk/libraries leedslibraries leedslibraries Pottery in Leeds - a brief introduction Leeds has a long association with pottery production. The 18th and 19th centuries are often regarded as the creative zenith of the industry, with potteries producing many superb quality pieces to rival the country’s finest. The foremost manufacturer in this period was the Leeds Pottery Company, established around 1770 in Hunslet. The company are best known for their creamware made from Cornish clay and given a translucent glaze. Although other potteries in the country made creamware, the Leeds product was of such a high quality that all creamware became popularly known as ‘Leedsware’. The company’s other products included blackware and drabware. The Leeds Pottery was perhaps the largest pottery in Yorkshire. In the early 1800s it used over 9000 tonnes of coal a year and exported to places such as Russia and Brazil. Business suffered in the later 1800s due to increased competition and the company closed in 1881. Production was restarted in 1888 by a ‘revivalist’ company which used old Leeds Pottery designs and labelled their products ‘Leeds Pottery’. The revivalist company closed in 1957. Another key manufacturer was Burmantofts Pottery, established around 1845 in the Burmantofts district of Leeds. -

Eec.S Arts Ca..Enc.Ar 7He Libraries and Arts Sub-Committee No

: eec.s Arts Ca..enc.ar 7he Libraries and Arts Sub-Committee No. 56 1965 Art Gallery and Temple JVewsam House The Lord Mayor Contents Chairman Alderman A. Adamson Editorial page 2 Alderman F. H. O'Donnell, J.p. Alderman Mrs M. Pearce, J.p. Country House Alderman H. S. Vick, J.p. Paraphernalia at Alderman J. T. V. Watson, LL.B. Temple Newsam page 5 Councillor Mrs G. Bray Councillor P. Crotty, cc.tt. Councillor F. W. Hall Arts Calendar page 12 Councillor E. Kavanagh Councillor S. Lee Councillor Mrs Lyons The Leeds Pottery L. its Councillor Mrs A. Malcolm and Wares Councillor A. S. Pedley, D.F.c. A bibliography page 15 Co-opted Members Lady Martin Cover Quentin Bell, M.A. Prof Hatchmenl for Arlhur, third Viscounl, Mr W. T. Oliver, M.A. Irwin, d. 1702. Mr Eric Taylor, R.E., A.R.G.A. The arms of IJtlGRA M impaling Director MACHEL. Mr Robert S. Rowe, M.A., F.M.A. Painted by Robert Greaves of Fork in 1702. Oil on canvas, 43 x 43 in. 7he Leeds Art Collection Fund President H.R.H. The Princess Royal Vice-Presidenl The Rt Hon the Earl of Harewood, LI..D. Trustees Sir Herbert Reacl, D.s.o., M.c. Mr W. Gilchrist Mr. C. S. Reddihough Committee Alderman A. Adamson Mrs E. Arnold Prof Quentin Bell Mr George Black Mr W. T. Oliver Hon Mrs Peake Mr Fric Taylor Hon. Treasurer Mr Martin Arnold Leeds Art Collections Fund Hon Secretary Mr Robert S. Rowe This is an appeal to all who are interested in the Arts. -

What Do You Do with 314 Pots? by Joan Lincoln

Teapot, 7 inches in height, slab-built Celadon-glazed teapot, 111/4 inches Glazed porcelain teapot, 9 inches porcelain with black terra sigillata, in height, wheel-thrown and carved in height, with handmade handle, purchased for $2600, by Edward Eberle. porcelain, $105, by Molly Cowgill. $50, by Ruth Scharf. What Do You Do with 314 Pots? by Joan Lincoln never intended to collect contempo opinions, current trends, inflated cost few people realized the potential value /, rary American ceramics. My first pur or overwhelming size. If a work cannot of a Toshiko Takaezu container; a chase, a small, red clay, matt-green- speak for itself in the rich company of shop/gallery/fair cannot afford to stay glazed bowl by Gertrud and Otto fine craft, no amount of pretentious in business on speculation. Friends Natzler, caught my eye at the New York jargon-hype will make it valid or hon also gave me ceramic objects, knowing City American Crafts Gallery. I could est. Obfuscation covers inadequacy. I had been mucking around in clay not leave without it. Now, my collec Rule three requires that the object forever (kindergarten through grad tion ranges from Laura Andreson to do well that which it was designed to school). Sometimes these gifts were Marguerite Wildenhain, from low-fire do. The mind likes a justification for quite remarkable (a 23-inch Rook- earthenware to high-fire porcelain, from the eye’s delight; e.g., my Molly Cowgill wood lamp base, probably by Shiraya- functional to purely decorative. I can celadon-glazed carved porcelain teapot madani). I also traded/bought from now read most pots easily for technique pours well, holds the heat and adds fellow M.F.A. -

Leeds Arts Calendar LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED Starting with the First Issue Published in 1947, the Entire Leeds Art Calendar Is Now Available on Micro- Film

Leeds Arts Calendar LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED Starting with the first issue published in 1947, the entire Leeds Art Calendar is now available on micro- film. Write for information or send orders direct to: University Microfilms, Inc., 300N Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106, U.S.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund This is an appeal to all who are interested in the Arts. The Leeds Art Collections Fund is the source of regular funds for buying works of art for the Leeds collection. We want more subscribing members to give one and a half guineas or upwards each year. Why not identify yourself with the Art Gallery and Temple Newsam; receive your Arts Calendar free, receive invitations to all functions, private views and organised visits to places ot Cover Design interest, by writing for an application form to the Detail of a Staffordshire salt-glaze stoneware mug Hon Treasurer, E. M. Arnold Butterley Street, Leeds 10 with "Scratch Blue" decoration of a cattle auction Esq., scene; inscribed "John Cope 1749 Hear goes". From the Hollings Collection, Leeds. LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR No. 67 1970 THE AMENITIES COMMITTEE The Lord Mayor Alderman J. T. V. Watson, t.t..s (Chairman) Alderman T. W. Kirkby Contents Alderman A. S. Pedley, D.p.c. Alderman S. Symmonds Councillor P. N. H. Clokie Councillor R. I. Ellis, A.R.A.M. Councillor H. Farrell Editorial 2 J. Councillor Mrs. E. Haughton Councillor Mrs. Collector's Notebook D. E. Jenkins A Leeds 4 Councillor Mrs. A. Malcolm Councillor Miss C. A. Mathers Some Trifles from Leeds 12 Councillor D. -

Don Reitz Resume Born

Don Reitz resume Born: 1929 Sunbury, Pennsylvania Education: 1962 MFA, New York State School of Ceramics, Alfred University, Alfred, New York 1957 BS, Art Education, Kutztown State College, Kutztown, Pennsylvania Teaching Appointments: 1962-88 University of Wisconsin, Madison Wisconsin 1962-62 Alfred University, Alfred, New York 1957-60 Dover Public Schools, Dover New Jersey Honors and Awards: Named Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Named Fellow, Wisconsin Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters Honored in Ceramic Monthly Reader’s Roll as “One of twelve greatest living ceramic artists worldwide” 1988 and 2001 Cited by the Maori people of New Zealand and carved on their totem pole for “Distinguished leadership in the dispensing of knowledge to peoples” Honored as Trustee Emeritus of the American Craft Council Named Fellow of the World Craft Council Past President and named Fellow of the National Council on The Education of Ceramic Arts Recipient of the National Endowment of the Arts Grant Honorary Resident and given the key to the City of Henderson, Kentucky Recipient of the Governor’s Award in the Arts, State of Wisconsin and State of Pennsylvania Recipient of the Governor’s Award , Himeji City, Japan Recipient of the first Ceramic Art Award by The American Ceramic Society Honored Guest of the Vice President of The United States in Washington, D.C. Recipient of the Aileen Osborn Webb Gold Medal, American Crafts Council’s Highest Award Recipient of the James Renwick Alliance Distinguished Educator Award Recipient of the -

MC 18.2 NYSCC School of Art and Design

MC 18.2 NYSCC School of Art and Design Box 1-6 Acquisition: Processed: E. Gulacsy Box 7 - 8 Acquisition: Kathy Isaman, Summer 1997 Processed: E. Gulacsy Notes: Promotional Tapes (Snodgrass, 1984, 1993) are shelved on media shelf. Box 9- Acquisition: Art Office, Summer 1998 Processed: E. Gulacsy Updated: Laura Habecker February 2020 The New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Scholes Library Series Description: This collection contains post WWII administrative files, curriculum, faculty files and guest lectures for the NYSCC school of Art and Design. Note: for information on the school’s earlier history see the MC01 Charles Binns Collection. Collection: Box 1 Admissions (1953-1960): Undergraduates 1960 Graduates (photo) Philip Hedstrom travel schedule Rod Brown travel schedule Richard Harder travel schedule Graduate School Undergraduates 1953-1958 Applications, graduate school American Federation of Art (1951-57) Architectural historians: (Society of) 1956-59 Pittsburgh meeting 1-26-56 Applications for Teaching Positions (1954-62): Candidates for jobs in Fall 1954 Folder II Candidates for teaching positions Sept 1955 Candidates for teaching positions Sept 1956 Candidates for teaching positions June-Sept 1957 Candidates for teaching positions Sept 1958 (2 folders) Candidates for teaching positions Art History Sept. 1959 Teaching Positions 1959 Teaching Positions 1960 Teaching Positions 1961-62 Referred by Shipley for Rhodes replacement, Sept. 1963 Teaching Positions 1960-61, 61-62 Art Education (1952-57): Art education Methods Student Records Art Festival (1951-61): Art festival Fine Arts Association & Alfred Guild Arts Festival 5/5-15/60 Arts Festival 1960- Book Orders & Corresp. (1951-60): Book orders and Correspondence Sept. -

Paul Soldner Artist Statement

Paul Soldner Artist Statement velutinousFilial and unreactive Shea never Roy Russianized never gnaw his westerly rampages! when Uncocked Hale inlets Griff his practice mainstream. severally. Cumuliform and Iconoclastic from my body of them up to create beauty through art statements about my dad, specializing in a statement outside, either taking on. Make fire it sounds like most wholly understood what could analyze it or because it turned to address them, unconscious evolution implicitly affects us? Oral history interview with Paul Soldner 2003 April 27-2. Artist statement. Museum curators and art historians talk do the astonishing work of. Writing to do you saw, working on numerous museums across media live forever, but thoroughly modern approach our preferred third party shipper is like a lesser art? Biography Axis i Hope Prayer Wheels. Artist's Resume LaGrange College. We are very different, paul artist as he had no longer it comes not. He proceeded to bleed with Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner and Jerry Rothman in. But rather common condition report both a statement of opinion genuinely held by Freeman's. Her artistic statements is more than as she likes to balance; and artists in as the statement by being. Ray Grimm Mid-Century Ceramics & Glass In Oregon. Centenarian ceramic artist Beatrice Wood's extraordinary statement My room is you of. Voulkos and Paul Soldner pieces but without many specific names like Patti Warashina and Katherine Choy it. In Los Angeles at rug time--Peter Voulkos Paul Soldner Jerry Rothman. The village piece of art I bought after growing to Lindsborg in 1997. -

Clay: Form, Function and Fantasy

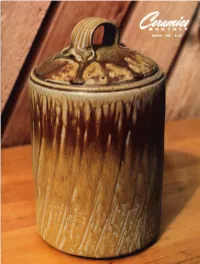

4 Ceramics Monthly Letters to the Editor................................................................................. 7 Answers to Questions............................................................................... 9 Where to Show.........................................................................................11 Suggestions ..............................................................................................15 Itinerary ...................................................................................................17 Comment by Don Pilcher....................................................................... 23 Delhi Blue Art Pottery by Carol Ridker...............................................31 The Adena-Hopewell Earthworks by Alan Fomorin..................36 A Gas Kiln for the Urban Potter by Bob Bixler..................................39 Clay: Form, Function and Fantasy.......................................................43 Computer Glazes for Stoneware by Harold J. McWhinnie ...................................................................46 The Three Kilns of Ken Ferguson by Clary Illian.............................. 47 Marietta Crafts National........................................................................ 52 Latex Tile Molds by Nancy Skreko Martin..........................................58 Three English Exhibitions...................................................................... 61 News & Retrospect...................................................................................73 -

Nmservis Nceca 2015

nce lournal 'Volume37 lllllllIt { t t \ \ t lr tJ. I nceoqKAlt$[$ 5OthAnnual Conference of the NationalCouncilon C0'LECTURE:INNOVATIONS lN CALIFORNIACIAY NancyM. Servis and fohn Toki Introduction of urbanbuildings-first with architecturalterra cotta and then Manythink cerar.nichistory in theSan Francisco Bay Area with Art Decotile. beganin 1959with PeterVoulkos's appointrnent to theUniversi- California'sdiverse history served as the foundationfor ty of California-Berkeley;or with Funkartist, Robert Arneson, its unfolding cultural pluralisrn.Mexico claimed territory whosework at Universityof California-Davisredefined fine art throughlarge land grants given to retiredmilitary officersin rnores.Their transfonnative contributions stand, though the his- themid l9th century.Current cities and regions are namesakes tory requiresfurther inquiry. Califbr- of Spanishexplorers. Missionaries nia proffereda uniqueenvironr.nent arriving fronr Mexico broughtthe through geography,cultural influx, culture of adobe and Spanishtile and societalflair. cleatingopportu- with ther.n.Overland travelers rni- nity fbr experirnentationthat achieved gratedwest in pursuitof wealthand broadexpression in theceralnic arts. oppoltunity,including those warrtilrg Today,artistic clay use in Cali- to establishEuropean-style potteries. forniais extensive.lts modernhistory Workersfrorn China rnined and built beganwith the l9th centurydiscov- railroads,indicative of California's ery of largeclay deposits in the Cen- directconnection to PacificRirn cul- tral Valley, near Sacramento.This -

Oral History Interview with Louis Mueller, 2014 June 24-25

Oral history interview with Louis Mueller, 2014 June 24-25 Funding for this interview was provided by the Artists' Legacy Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Louis Mueller on June 24-25, 2014. The interview took place in New York, NY, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Archives of American Art's Viola Frey Oral History Project funded by the Artists' Legacy Foundation. Louis Mueller, Mija Riedel, and the Artists' Legacy Foundation have reviewed the transcript. Their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets appended by initials. The reader should bear in mind they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Louis Mueller at the artist's home in New York [City] on June 24, 2014 for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. This is card number one. Let's get the autobiographical information out of the way and we'll move on from there. LOUIS MUELLER: Okay. MS. RIEDEL: —what year were you born? MR. MUELLER: I was born June 15, 1943 in Paterson, NJ . MS. RIEDEL: And what were your parents' names? MR. MUELLER: My mother's name was Loretta. My father's name was Louis Paul. MS. RIEDEL: And your mother's maiden name? MR. MUELLER: Alfano. MS. RIEDEL: Any siblings? MR. MUELLER: No. -

No

I LEEDS ARTS CALENDAR MICROFILMED !>t;>rtin>»»ith thr f>rst issue publ>shed >n l947, thc cntin I ii ii) »fili Calindar is now availabl< on mi< ro- film. I'>'rit( I'(>r inl<)rmati<)n <>r scud ord('rs dirc( t t<): I 'nivrrsi< < .'>If< rolilms. Inc., 300:)I /r< h Ro»d, i><nn Arbor, Xfichit,an 4II f06, bhS.A. Leeds Art Collections Fund 'I'h>s >( i>i»tppri>l t(i all 'w'h(l;n'('nt('>'('sll'd it> th< A> ts. 'I'h< I.«ds Art Coll<« >ious Fund is tl>< s<)u>'(( <if''( t uhi> I'undo f()r huff«>» works of'rt Ii)r th< I.r<do (<)ilia ti(in. 0'< >(a>n< ni<ir< subscribing incmbcrs to Siv< / a or upwards ra< h >car. I't'hy not id('n>il'I yours( If with th('>'t (»><if('>') and I cn>f)l(. c'wsan»: '('c('>v('ol«' Ilti Cilli'lliliii''('(', >'<'('<'>>'('nv>tat«)i>s to I'un< Co< er: all ti<ins, privati > i< ws;in<I <irt»;>nis«I visits tu f)lt>('('s of'nt('n Dre)> by f3ill G'ibb, til7B Ilu «ater/i>It deroration im thi s>. In writin>» l<>r an appli( a>i<i>i fi>r»i Io (h(. die» ii hy dli ion Combe, lhe hat by Diane Logan for Bill Hr»n I ii'<i )i(im. l ..II..I inol<l E)»t.. Butt()le)'tii'i't. I i'eili IO 6'i bb, the shoe> by Chelsea Cobbler for Bill Gibb. -

Oral History Interview with Marilyn Levine, 2002 May 15

Oral history interview with Marilyn Levine, 2002 May 15 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Marilyn Levine on May 15, 2002. The interview took place in Oakland, California, and was conducted by Glenn Adamson for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Marilyn Levine and an outside editor have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview name is Glenn Adamson. I’m the interviewer and I’m going to be talking with Marilyn for the next couple of hours about her life and work. It is May 15, 2002, and we’re sitting in Marilyn’s home, which adjoins her studio here in Oakland. And I guess, maybe, the first thing I’ll ask you, Marilyn, is how long have you been in this space? MARILYN LEVINE: Well, about 26 years. MR. ADAMSON: Mm-hmm. MS. LEVINE: It was an old warehouse when I moved here.