ONE Magazine and Its Readers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jun Jul. 1970, Vol. 14 No. 09-10

Published bi-monthly by the Daughters of ONCE MORE WITH FEELING Bilitis, Inc., a non-profit corporation, at THE I have discovered my most unpleasant task as editor . having to remind y. 'i P.O. Box 5025, Washington Station, now and again of your duty as concerned reader. Not just reader, concern« ' reader. Reno, Nevada 89503. UDDER VOLUME 14 No. 9 and 10 If you aren’t — you ought to be. JUNE/JULY, 1970 Those of you who have been around three or more years of our fifteen years n a t io n a l OFFICERS, DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS, INC know the strides DOB has made and the effort we are making to improve this magazine. To continue growing as an organization we need more women, women . Rita Laporte aware they are women as well as Lesbians. If you have shy friends who might be President . jess K. Lane interested in DOB but who are, for real or imagined reasons, afraid to join us — i t h e l a d d e r , a copy of WHAT i w r ■ ’ '^hich shows why NO U N t at any time in any way is ever jeopardized by belonging to DOB or by t h e LADDER STAFF subscribing to THE LADDER. You can send this to your friend(s) and thus, almost surely bring more people to help in the battle. Gene Damon Editor ....................... Lyn Collins, Kim Stabinski, And for you new people, our new subscribers and members in newly formed and Production Assistants King Kelly, Ann Brady forming chapters, have you a talent we can use in THE LADDER? We need Bobin and Dana Jordan wnters always in all areas, fiction, non-fiction, biography, poetry. -

The Year 1969 Marked a Major Turning Point in the Politics of Sexuality

The Gay Pride March, begun in 1970 as the In the fertile and tumultuous year that Christopher Street Liberation Day Parade to followed, groups such as the Gay commemorate the Stonewall Riots, became an Liberation Front (GLF), Gay Activists annual event, and LGBT Pride months are now celebrated around the world. The march, Alliance (GAA), and Radicalesbians Marsha P. Johnson handing out flyers in support of gay students at NYU, 1970. Photograph by Mattachine Society of New York. “Where Were Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. which demonstrates gays, You During the Christopher Street Riots,” The year 1969 marked 1969. Mattachine Society of New York Records. sent small groups of activists on road lesbians, and transgender people a major turning point trips to spread the word. Chapters sprang Gay Activists Alliance. “Lambda,” 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. Gay Liberation Front members marching as articulate constituencies, on Times Square, 1969. Photograph by up across the country, and members fought for civil rights in the politics of sexuality Mattachine Society of New York. Diana Davies. Diana Davies Papers. “Homosexuals Are Different,” 1960s. in their home communities. GAA became a major activist has become a living symbol of Mattachine Society of New York Records. in America. Same-sex relationships were discreetly force, and its SoHo community center, the Firehouse, the evolution of LGBT political tolerated in 19th-century America in the form of romantic Jim Owles. Draft of letter to Governor Nelson A. became a nexus for New York City gays and lesbians. Rockefeller, 1970. Gay Activists Alliance Records. friendships, but the 20th century brought increasing legal communities. -

OUT of the PAST Teachers’Guide

OUT OF THE PAST Teachers’Guide A publication of GLSEN, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network Page 1 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Why LGBT History? 2 Goals and Objectives 3 Why Out of the Past? 3 Using Out of the Past 4 Historical Segments of Out of the Past: Michael Wigglesworth 7 Sarah Orne Jewett 10 Henry Gerber 12 Bayard Rustin 15 Barbara Gittings 18 Kelli Peterson 21 OTP Glossary 24 Bibliography 25 Out of the Past Honors and Awards 26 ©1999 GLSEN Page 2 Out of the Past Teachers’ Guide Why LGBT History? It is commonly thought that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered (LGBT) history is only for LGBT people. This is a false assumption. In out current age of a continually expanding communication network, a given individual will inevitably e interacting with thousands of people, many of them of other nationalities, of other races, and many of them LGBT. Thus, it is crucial for all people to understand the past and possible contributions of all others. There is no room in our society for bigotry, for prejudiced views, or for the simple omission of any group from public knowledge. In acknowledging LGBT history, one teaches respect for all people, regardless of race, gender, nationality, or sexual orientation. By recognizing the accomplishments of LGBT people in our common history, we are also recognizing that LGBT history affects all of us. The people presented here are not amazing because they are LGBT, but because they accomplished great feats of intellect and action. These accomplishments are amplified when we consider the amount of energy these people were required to expend fighting for recognition in a society which refused to accept their contributions because of their sexuality, or fighting their own fear and self-condemnation, as in the case of Michael Wigglesworth and countless others. -

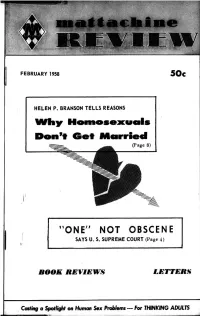

''One" Not Obscene Book Reviews Letters

FEBRUARY 1958 50c HELEN P. BRANSON TELLS REASONS Whx Homosexuals Don’t Get Married (Page 8) ’’ONE" NOT OBSCENE SAYS U. S. SUPREME COURT (Page 4) BOOK REVIEWS LETTERS Casting a Spotlight on Human Sox Problom s — For THINKING ADULTS ■ nattachf ne O ffici Of THf S04*D Of DI«ECrO*S inattachine ^rittg, M.. Copyright1 295S by the Matlacbine Society, incorporated FOURTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION-UATTACHIHE REVIEW founded January 1955 Mauaebint Foundation establisbid 1950; M<tttacbine*Society, Inc., ebartered 2954 OBSCENITY NEEDS TO BE DEFINED Volume IV FEBRUARY 1958 Number 2 The declaration by the U. S. Supreme Court that ONE magazine is not obscene (see page 4) is a victory for freedom of expression everywhere in the U. S., and not a gain for the 'homosexual press' Comtemt» alone. ARTICLES Changing times, changing attitudes and the general progress of human civilization call for old standards to be examined critically VICTORY FOR ONE by John Logan.........................................4 from time to time. The vague old bogey of obscenity is one of HOMOSEXUALS AS I SEE THEM by Helen P. Branson.. 8 these and within the past year or so sponsors of censorship on ob ENIGMA UNDER SCRUTING by Sexology Research Staff..14 scenity grounds have been called to task mote than once, but the right of Federal and State governments to judge and ban obscene SHORT FEATURES material has been upheld, as we believe it should be (see MATTA’ COURT RELEASES KINSEY MATERIAL..................................5 CHINE REVIEW. July 1957). We believe that ONE and MATTACHINE agree that freedom to CUSTOMS’ SEVEN-YEAR ITCH IS SCRATCHED............6 publish educational information, in an interesting and readable SOCIETY FOR THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF SEX..........7 form, on the subject of sex variation is a genuine service in the ARMY REVIEWS RISK DISCHARGES.......................................14 interest of truth, justice and human well-being. -

January 27, 1961: the Birth of Gaylegal Equality Arguments

\\Server03\productn\N\NYS\58-1\NYS111.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-FEB-02 15:54 JANUARY 27, 1961: THE BIRTH OF GAYLEGAL EQUALITY ARGUMENTS WILLIAM N. ESKRIDGE, JR.* In 1956, it was not exactly illegal to be a ªhomosexualº in the United States, but it was a felony to make love to anyone of the same sex, and mere suspicion of homosexuality could cost a citizen her livelihood. Dr. Franklin Kameny, a Harvard-educated (Ph.D.) astronomer, was arrested in August of that year for allegedly solicit- ing sex from an undercover police officer. Because the charges were expunged after a probationary period, Kameny's application for a position with the Army Map Service identified the incident as one in which the plea was ªnot guiltyº and the charge was ªdis- missed.º1 This description of the incident was technically correct under state law, but when the Army learned of the underlying charge, it concluded that Kameny had not been sufficiently forth- coming. The Army dismissed him, and the Civil Service Commis- sion (ªCSCº) barred him from federal employment for several years. The employment bar also automatically prevented Kameny from obtaining security clearances needed for virtually any private sector job in his field. That Kameny lost his job over a minor incident suggesting his homosexuality was nothing new in the period after World War II. Nor was the irony of his situation particularly unusual: dismissals from federal or state government service were just as likely to be based upon the failure of a government employee to be completely * John A. -

Mattachine Society by Craig Kaczorowski

Mattachine Society by Craig Kaczorowski Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com One of the earliest American gay movement (or homophile) organizations, the Mattachine Society began in Los Angeles in the winter of 1950. It was formed by Harry Hay, a leading gay activist and former Communist Party member, along with seven other gay men. The name refers to the Société Mattachine, a French medieval masque group that allegedly traveled from village to village, using ballads and dramas to point out social injustice. The name was meant to symbolize the fact that "gays were a masked people, unknown and anonymous." By sharing their personal experiences as gay men and analyzing homosexuals in the context of an oppressed cultural minority, the Mattachine founders attempted to redefine the meaning of being gay in the United States. They devised a comprehensive program for cultural and political liberation. In 1951, the Mattachine Society adopted a Statement of Missions and Purpose. This Statement stands out in the history of the gay liberation movement because it identified and incorporated two important themes. First, Mattachine called for a grassroots movement of gay people to challenge anti-gay discrimination; and second, the organization recognized the importance of building a gay community. The Mattachine Society also began sponsoring discussion groups in 1951, providing lesbians and gay men an opportunity to share openly, often for the first time, their feelings and experiences. The meetings were frequently emotional and cathartic. Over the next few years attendance at Mattachine meetings increased tremendously. Soon discussion groups were meeting throughout the United States. -

Guide to the One Archives Cataloging Project: Founders and Pioneers

GUIDE TO THE ONE ARCHIVES CATALOGING PROJECT: FOUNDERS AND PIONEERS FUNDED BY THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES ONE NATIONAL GAY & LESBIAN ARCHIVES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA GUIDE TO THE ONE ARCHIVES CATALOGING PROJECT: FOUNDERS AND PIONEERS Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Grant #PW-50526-10 2010-2012 Project Guide by Greg Williams ONE NATIONAL GAY & LESBIAN ARCHIVES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES, 2012 Copyright © July 2012 ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives Director’s Note In October 1952, a small group began meeting to discuss the possible publication and distribution of a magazine by and for the “homophile” community. The group met in secret, and the members knew each other by pseudonyms or first names only. An unidentified lawyer was consulted by the members to provide legal advice on creating such a publication. By January 1953, they created ONE Magazine with the tagline “a homosexual viewpoint.” It was the first national LGBTQ magazine to openly discuss sexual and gender diversity, and it was a flashpoint for all those LGBTQ individuals who didn’t have a community to call their own. ONE has survived a number of major changes in the 60 years since those first meetings. It was a publisher, a social service organization, and a research and educational institute; it was the target of major thefts, FBI investigations, and U.S. Postal Service confiscations; it was on the losing side of a real estate battle and on the winning side of a Supreme Court case; and on a number of occasions, it was on the verge of shuttering… only to begin anew. -

REVOLT HOMOSEXUAL Mattaclilne PUBLICATIONS for SALE by the MATT ACHINE SOCIETY Publuhed Monthly

m att acht DC 50c MAY 1959 REVOLT HOMOSEXUAL mattaclilne PUBLICATIONS FOR SALE BY THE MATT ACHINE SOCIETY PublUhed Monthly. Copyright 1959 by Mottochlno Soeloty, Ine. Available now from the National Headquarters of the Mattachine Soci V olum e V MAY 1959 N um ber 5 ety are the following publications at the prices indicated. Please send remittance with order. AH orders sent postpaid. CONTENTS MATTACHINE SOCIETY TODAY (Yellow Booklet of General Informa REVOLT OF THE HOMOSEXUAL tion) 1958 Edition. 24 pages. Gives general outline of Society, aims and by Seymour Krim ..................... .... 3 principles, how to form an Area Council, lists discussion group topics McREYNOLDS REPLIES TO KRIM and ideas, tells brief history of Society and what Mattaciiine does. 25 I by David McReynolds..........................8 cents. GREETINGS by C. V. Howard............................... 13 CONSTITUTION AND BY-LAWS (Blue Book of Official Information) WHOM SHOULD WE NOT TELL? 1959 Edition. 16 pages. Contains revised constitution, by-laws add by Stanley Norman ..............................15 articles of incorporation. 25 cents. ^ BOOK REVIEW : The F lam in g H e a rt............... 18 INFORMATION FOLDERS: “ In Case You Didn’t Know,” and "What CALLING SHOTS..................................................... 19 Does Mattachine Do.” Designed to be used as companion mailing pieces. NEGLECTED ART OF BEING DIFFERENT First tells of existence of homosexuality and purpose of Mattachine. by Arthur Gordon................................22 Second describes in detail the projects and functions of the Sdciety, along with the services it performs. 100 for $1.50; 50 for $1.00; smaller READERS WRITE................ 23 quantities, 3 cents each. Unless specified, orders will be fiUed with PROBLEM OF YOUTH WHOSE SEX IS MIXED UP an equal quantity of each. -

LGBTQ History Cards

LGBTQ History Cards Antinous, a 19-year-old man who Francis Bacon, a noted gay man was the Roman Emperor Hadrian’s who coined the term “masculine favorite lover, mysteriously dies love,” publishes “The Advancement in the Roman province of Egypt. of Learning—an argument for Richard Cornish of the Virginia After finding out about Antinous’s empirical research and against Colony is tried and hanged for death, Hadrian creates a cult that superstition.” This deductive sodomy. gave Antinous the status of a god system for empirical research and built several sculptures of him earned him the title “the Father of throughout the Roman Empire. Modern Science.” The first known conviction for Thomas Cannon wrote what may be lesbian activity in North America Thomas Jefferson revises Virginia the earliest published defense of occurs in March when Sarah law to make sodomy (committed homosexuality in English, “Ancient White Norman is charged with by men or women) punishable by and Modern Pederasty Investigated “lewd behavior” with Mary mutilation rather than death. Vincent Hammon in Plymouth, and Exemplify’d.” Massachusetts. We’wha, a Zuni Native American from New Mexico, is received by The Well of Loneliness, by U.S. President Grover Cleveland Henry Gerber forms the Society for Radclyffe Hall, is published as a “Zuni Princess.” They are Human Rights, the first gay group in the US. This sparks great an accomplished weaver, potter, in the United States, but the group legal controversy and brings the and the most famous Ihamana, a is quickly shut down. topic of homosexuality to public traditional Zuni gender role, now conversation. -

May 1961 Mattachine Review

mattaclpine AUTHOR TKilj iq'61 i y d k / u t 50’ ECHOES OF PURITAN TERROR ............ Letters ptotesting wbst readers regard as unlawful action of Mnssaebuaetts author* ■ nattiicliine( ities as repotted in "Puritan Terror— Maasacfausetta 1961." in April REVIEW are beginning to arrive. Two ate published below, and mote will appear in the June issue. The first is from a person who cannot be identified: mrzw REVIEW EDITORi It is depressing to Founded in 1954-Fits! Issue January 1955 read of the outrage upon human beings my lifetim e, and I am very young. Cata committed by other human beings, as re clysmic changes lie ahead. I just hope lated in "Puritan Terror," and in the let that man doesn't succeed in reaching other planets. But enough of that: Pre ter from a mother in Minnesota, As a for Volume VII M AY 1961 Number 5 mer resident of the Commonwealth of dictions don’t change the course of his M assachusetts for four years, I can test tory. Editor HAROLD L. CALL ify that such official activity is entirely REVIEW EDITOR: Thanks for your fine consistent with the ethical qualities mani and fearless repotting in the moving art TABU CONTENTS fested in many other spheres by many of icle about the Puritan Terror in Massa Of the people of the state and their repre chusetts, 1961. Since this illegal out sentatives, For life in Massachusetts is rage might possibly set some kind of hor characterized by an all-pervading corrup fittsinwss M anafr rible precedent, Mattachine must see that DONALD S. -

Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections

Legacy Finding Aid for Manuscript and Photograph Collections 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. 20001 What are Finding Aids? Finding aids are narrative guides to archival collections created by the repository to describe the contents of the material. They often provide much more detailed information than can be found in individual catalog records. Contents of finding aids often include short biographies or histories, processing notes, information about the size, scope, and material types included in the collection, guidance on how to navigate the collection, and an index to box and folder contents. What are Legacy Finding Aids? The following document is a legacy finding aid – a guide which has not been updated recently. Information may be outdated, such as the Historical Society’s contact information or exact box numbers for contents’ location within the collection. Legacy finding aids are a product of their times; language and terms may not reflect the Historical Society’s commitment to culturally sensitive and anti-racist language. This guide is provided in “as is” condition for immediate use by the public. This file will be replaced with an updated version when available. To learn more, please Visit DCHistory.org Email the Kiplinger Research Library at [email protected] (preferred) Call the Kiplinger Research Library at 202-516-1363 ext. 302 The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation’s capital. Founded in 1894, it serves a diverse audience through its collections, public programs, exhibits, and publications. 801 K Street NW Washington, D.C. -

Nick Ota-Wang the Queen City: Denver's Homophile Organizations

Ota-Wang 1 Nick Ota-Wang The Queen City: Denver’s Homophile Organizations from 1950-1970 May 2020 This is an unpublished article. For questions please email the author at [email protected]. 1 1 1959 Newsletter Cover, Gay Organizations, Denver Area Council Mattachine Society, July 1957 – December 1959. July 1957-December, 1959. MS The Mattachine Society of New York Records, 1951-1976: Series 3. Gay Organizations Box 7, Folder 10. New York Public Library. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, Ota-Wang 2 Life in the United States prior to 1950 for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) individuals is unlike life today. LGBT individuals today can live Without fear of arrest, harassment, or exposure for being Who they are. Mid-twentieth century America did not provide a safe place for LGBT individuals to be themselves. Exposure for being a member of the LGBT community Would lead to life changing events for individuals. The LGBT community feared arrest, and the police. Individuals could be arrested at a private gathering or party, in a gay bar, or soliciting sex in any location (including private homes).2 If an individual Was arrested on a “morals charge” their life changed. The “morals charge” is hoW the police department could quickly and easily arrest anyone they suspected of being homosexual. LGBT individuals faced social stigma, incarceration, commitment to mental institutions, losing jobs, and being ousted by family and friends. 3 Because of the vast consequences LGBT individuals faced if their identity Was ever exposed, the need to keep their identity a secret Was important.