Confessions of a Yakuza I WANT IT in WRITING: I.O.U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VAGRANT RECORDS the Lndie to Watch

VAGRANT RECORDS The lndie To Watch ,Get Up Kids Rocket From The Crypt Alkaline Trio Face To Face RPM The Detroit Music Fest Report 130.0******ALL FOR ADC 90198 LOUD ROCK Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS Talkin' Dirty With Matt Zane No Motiv 5319 Honda Ave. Unit G Atascadero, CA 93422 HIP-HOP Two Decades of Tommy Boy WEEZER HOLDS DOWN el, RADIOHEAD DOMINATES TOP ADDS AIR TAKES CORE "Tommy's one of the most creative and versatile multi-instrumentalists of our generation." _BEN HARPER HINTO THE "Geggy Tah has a sleek, pointy groove, hitching the melody to one's psyche with the keen handiness of a hat pin." _BILLBOARD AT RADIO NOW RADIO: TYSON HALLER RETAIL: ON FEDDOR BILLY ZARRO 212-253-3154 310-288-2711 201-801-9267 www.virginrecords.com [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2001 VIrg. Records Amence. Inc. FEATURING "LAPDFINCE" PARENTAL ADVISORY IN SEARCH OF... EXPLICIT CONTENT %sr* Jeitetyr Co owe Eve« uuwEL. oles 6/18/2001 Issue 719 • Vol 68 • No 1 FEATURES 8 Vagrant Records: become one of the preeminent punk labels The Little Inclie That Could of the new decade. But thanks to a new dis- Boasting a roster that includes the likes of tribution deal with TVT, the label's sales are the Get Up Kids, Alkaline Trio and Rocket proving it to be the indie, punk or otherwise, From The Crypt, Vagrant Records has to watch in 2001. DEPARTMENTS 4 Essential 24 New World Our picks for the best new music of the week: An obit on Cameroonian music legend Mystic, Clem Snide, Destroyer, and Even Francis Bebay, the return of the Free Reed Johansen. -

UWM Libraries Digital Collections

Concert review: pg 13 David Byrne returns to Milwaukee uwMrOSl The Student-Run Independent Newspaper at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee The potential presidencies of V Obama and McCain compared Controversy over News pg 5 bookstore sweatshop allegations RunUp the Runway showcases local fashion designers Robert Spencer, founder of Jihad Watch, speaking Thursday evening in at MAM Bolton Hall. Post photo by Alana Soehartono Concert Reviews: Spencer lecture lacked Minus the Bear Mountain Goats outbursts, interruptions Man Man David Byrne Extensive Freedom Center is a conserva SDS claims stem from Bookstore, SDS approached the tive organization founded by UWM's refusal to join Brand Standards Committee security prevents Horowitz, who was the subject fringe pg 7 with a request that UWM reject of a controversial visit to UWM DSP program their support of two groups used Horowitz repeat this past spring. to assure all logo sale items are Prior to entering the lecture Women's soccer By Cordelia Ellis manufactured in a sweatshop By Jo Rey Lopez and Kevin Lessmiller hail, attendees had to endure an Special to The Post free environment with equal airport-like security screening, breaks season worker rights. With enough security to complete with a walk-through goal record The UW-Milwaukee Students SDS requested that UWM join quell a small riot, conservative metal detector, bag and purse for a Democratic Society (SDS) the Designated Supplier Program speaker Robert Spencer took the search, followed by another recently launched an anti-sweat (DSP), a proposed new system by stage in UW-Milwaukee's Bolton screening by a handheld metal "Kicks for Hoops" shop campaign, which claims WRC. -

RSD List 2020

Artist Title Label Format Format details/ Reason behind release 3 Pieces, The Iwishcan William Rogue Cat Resounds12" Full printed sleeve - black 12" vinyl remastered reissue of this rare cosmic, funked out go-go boogie bomb, full of rapping gold from Washington D.C's The 3 Pieces.Includes remixes from Dan Idjut / The Idjut Boys & LEXX Aashid Himons The Gods And I Music For Dreams /12" Fyraften Musik Aashid Himons classic 1984 Electonic/Reggae/Boogie-Funk track finally gets a well deserved re-issue.Taken from the very rare sought after album 'Kosmik Gypsy.The EP includes the original mix, a lovingly remastered Fyraften 2019 version.Also includes 'In a Figga of Speech' track from Kosmik Gypsy. Ace Of Base The Sign !K7 Records 7" picture disc """The Sign"" is a song by the Swedish band Ace of Base, which was released on 29 October 1993 in Europe. It was an international hit, reaching number two in the United Kingdom and spending six non-consecutive weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States. More prominently, it became the top song on Billboard's 1994 Year End Chart. It appeared on the band's album Happy Nation (titled The Sign in North America). This exclusive Record Store Day version is pressed on 7"" picture disc." Acid Mothers Temple Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo (Title t.b.c.)Space Age RecordingsDouble LP Pink coloured heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP Not previously released on vinyl Al Green Green Is Blues Fat Possum 12" Al Green's first record for Hi Records, celebrating it's 50th anniversary.Tip-on Jacket, 180 gram vinyl, insert with liner notes.Split green & blue vinyl Acid Mothers Temple & the Melting Paraiso U.F.O.are a Japanese psychedelic rock band, the core of which formed in 1995.The band is led by guitarist Kawabata Makoto and early in their career featured many musicians, but by 2004 the line-up had coalesced with only a few core members and frequent guest vocalists. -

The // Skyway \\ the Replacements Mailing List

the // skyway \\ the replacements mailing list issue #100 (november 24, 2016) info: www.theskyway.com www.facebook.com/thematsskyway send your submissions to [email protected] subscription info: you can send an email saying “subscribe skyway” (and hello) to [email protected] COLOR ME IMPRESSED 24 years later, issue #100. I'd say thank you for reading, but really I say thank you for writing. In the end, I have just collected and saved what everybody else has to say about the Replacements. I started because I wanted to hear what everyone else had to say and what memories they had of that band that I loved, from everywhere. So for this 100th issue, I asked 1024 Replacements fans all the questions you´d ask if you met for ten minutes and talked about their favorite band. People who hear the Replacements and just hear the sound of a loose, raucous bar band don't get why this group and its songs are held in such reverence in such a unique way. No matter which album you listen to, there is the spirit, the great songs, the guitar anthems, the colorful personalities, the legend itself of the band that could simultaneously be brilliant and a shambles and whose songs could make you simultaneously laugh and cry. The Replacements are a great story in how they failed at whatever hopes for mainstream success they pursued in a self- sabotaging way, only to reunite two decades later for a little over 30 shows only to become larger than ever and finally achieve the national acclaim they never had. -

Riverwest-Currents-July-2021-Issue

Pages 7 to 10 It’s Back, Sunday July 18. Ad. p16 FREE! News You Can Use • Riverwest, Harambee and The East Side Vol 20 Issue 7 JULY 2021 changed forever during your time. The way people worked and earned a living. The things that were being produced. The very values driving human life and activity were reexamined and significant changes were begun. This brings me to the point of this Letter from Zagora. It’s a call to action to each of you in the still active, still vibrant, still caring neighborhood of Riverwest. You need to come together at this time. You need to gather and discuss things. You need to decide on the things you are willing to fight for, the things his month’s 4-page centerspread — you are willing to work for, the things “Free Speech/Hate Speech/Outright you want to keep. TLies” — is by Barbara J. Miner, a And the things you are willing to writer/photographer/artist and longtime lose. resident of Riverwest. Miner, currently en- So. Let’s get to it. rolled in the Master of Fine Arts program Garden Park. Do you want to keep at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, it? used a variety of media to create the proj- Affordable housing. Do you want ect under the guidance of UWM professor to keep it? Jessica Meuninck-Ganger. Letter from Zagora: Discussions, Decisions, Destiny The right to vote. Do you want to Miner began the work in the fall of keep it? Garden Park , Prairie Garden July 2002, Vince Bushell 2020 and continued into 2021, increasingly Democracy. -

Irreplaceable Though Many Have Tried to Copy Them, There’S No Substitute for the Replacements

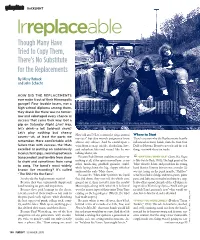

plalaylisylist BACKLIGHT Irreplaceable Though Many Have Tried to Copy Them, There’s No Substitute for the Replacements By Missy Roback and John Schacht HOW DID THE REPLACEMENTS ever make it out of their Minneapolis garage? Four lovable losers, not a high-school diploma among them, they drank like there was no tomor- row and sabotaged every chance at success that came their way. Got a gig on Saturday Night Live? Hey, Takin’ a Ride Left to right: Chris Mars, Bob Stinson, Paul Westerberg, and Tommy Stinson. let’s drink—a lot! Sold-out show? Let’s play nothing but cheesy Where to Start covers—uh, at least the parts we How old am I?/Let’s count the rings around my eyes” but also wrench poignancy from There’s a reason why the Replacements heavily remember. More comfortable with almost any subject. And he could open a influenced so many bands, from the Goo Goo failure than with success, the ’Mats vein about teenage suicide, alcoholism, love, Dolls to Nirvana. If you’ve never heard the real excelled at putting on notoriously and suburban life—and sound like he was thing, start with these ten tracks. inconsistent gigs, swerving between talking about you. transcendent and terrible from show Because Bob Stinson could wear a dress—or “SHIFTLESS WHEN IDLE” (Sorry Ma, Forgot to show and sometimes from song nothing at all, if the spirits moved him—as no to Take Out the Trash, 1981): The high point of the to song. The band’s most widely other lumbering goofball guitarist could, ’Mats’ abrasive debut, and proof that the young known live recording? It’s called while laying down the big, sloppy riffs that band (bassist Tommy Stinson was a tender 12) anchored the early ’Mats shows. -

Sfreeweekl Ysince | April

CHICAGO’SFREEWEEKLYSINCE | APRIL THIS WEEK CHICAGOREADER | APRIL | VOLUME NUMBER IN THIS ISSUE TR 08 NewsDoesthemayor’s astonishingimagesofhumanity’s - OPINION COVIDexecutiveorderputher impactontheplanet’stopography 30 IdentityandCultureSeeking @ onlightfooting? Roarisacaseagainstdisrupting safetyisn’tsoeasyifyou’rebattling 09 Dukmasova|PetsAnimal theanimalkingdomonawhim COVIDwhileBlack PTB sheltershavebeenoverwhelmed 31 ‘Americanness’Onrejecting ECS K KH CLR H withadoptionapplicationsduring antiAsianAmericanrhetoricand MEP M standinguptohate TDKR CEBW AEJL SWMD LG DI BJ MS EAS N L GD AH CITYLIFE L CSC-J 03 PublicService CEBN B AnnouncementZoomoverto L C M DLCMC J F S F JH I theseonlineclasses H C MJ MUSIC &NIGHTLIFE MKSK FOOD&DRINK 21 Galil|FeatureChristenThomas ND L JL MMAM -K 04 KeyIngredientIntroducing thepandemic bookedshowsforadecadewith J R N JN M O thefi rstinstallmentofPandemic 10 ImmigrationCoronavirusleaves theEmptyBottleandMetrobut 32 SavageLoveDanSavageoff ers M S CS PantryinwhichFunkenhausen’s immigrantstrappedinabyzantine thatworkwasjustthebeginning advicetoamanwhohasananxiety ---------------------------------------------------------------- MarkSteuermakesamiracleoutof courtsystemwithoutlawyersand ofthelovejoyandsupportshe attackwhenheseeshiswifenaked DD J D mushypasta morefrightenedthanever showeredonthescene D DCW SMCJ G 24 RecordsofNoteApandemic CLASSIFIEDS MPC ARTS&CULTURE can’tstopthefl owofgreatmusic 34 Jobs YD 13 Profi leBeforetherewasJoe Ourcriticsreviewreleasesthatyou 34 Apartments&Spaces SSP -

500 Songs That Shaped Rock

500 Songs That Shaped Rock James Henke, chief curator for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, with the help of music writers and critics, selected 500 songs (not only rock songs) that they belie e ha e been most influential in shaping rock and roll! "he list is alphabetical by artist! A AC/DC, #$ack in $lack% AC/DC, #Highway to Hell% Roy Acuff and the Smoky Mountain Boys, #&abash 'annonball% Aerosmith, #(ream )n% Aerosmith, #"oys in the *ttic% Afrika Bambaataa, #+lanet Rock% The Allman Brothers Band, #Ramblin, -an% The Allman Brothers Band, #&hipping +ost% The Animals, #"he House of the Rising .un% The Animals, #&e /otta /et )ut of "his +lace% Louis Armstrong, #&est 0nd $lues% Arrested De elo!ment, #"ennessee% B The B"#$%s, #Rock 1obster% 1 of 19 The B-#$%s La&ern Baker, #Jim (andy% 'ank Ballard and the Midnighters, #&ork &ith -e *nnie% The Band, #"he 2ight "hey (ro e )ld (i3ie (own% The Band, #"he &eight% Beach Boys, #'alifornia /irls% Beach Boys, #(on,t &orry $aby% Beach Boys, #/od )nly 4nows% Beach Boys, #/ood 5ibrations% Beach Boys, #.urfin, 6!.!*!% The Beastie Boys, #(7ou /otta) Fight for 7our Right (to +arty)% The Beatles, #* (ay in the 1ife% The Beatles, #Help8% The Beatles, #Hey Jude% The Beatles, #9 &ant to Hold 7our Hand% The Beatles, #2orwegian &ood% The Beatles, #.trawberry Fields Fore er% The Beatles, #7esterday% The Beau Brummels, #1augh 1augh% Beck, #1oser% (eff Beck )rou!, #+lynth (&ater (own the (rain)% The Bee )ees, #.tayin, *li e% Archie Bell and the Drells, #"ighten 6p% Chuck Berry, #Johnny $! /oode% 2 of 19 Chuck Berry, #-aybelline% Chuck Berry, #Rock and Roll -usic% The Big Bo!!er, #'hantilly 1ace% Big Brother and the 'olding Com!any, #+iece of -y Heart% Big Star, #.eptember /urls% Black Sabbath, #9ron -an% Black Sabbath, #+aranoid% Bobby Blue Bland, #"urn )n 7our 1o e 1ight% Blondie, #Heart of /lass% *urtis Blo+, #"he $reaks% )ary ,-S- Bonds, #:uarter to "hree% Booker T- . -

Formal Charges Brought Against Brown • by Garry George with Trabant out of Town Be Reached for Comment

Formal charges brought against Brown • by Garry George With Trabant out of town be reached for comment. the college upon its formation Executive Editor this week, no one in the ad ·Contacted at home, yester in 1976 and retained the post All parties concerned with ministration is willing to com day morning, Brown would not until he was appointed vice the ousting of ex-Vice Presi ment on formal charges that comment on the substance of president in 1978. Brown said, dent for personnel and have now been filed against the charges filed against him however, that he has no desire employee relations Dr. C. Brown. · The case is to be by the university, but was will to return to the position--"! on Harold Brown remain reviewed in an upcoming ing to talk about his position ly want to teach." tight-lipped. Faculty Senate hearing. with the university as he sees According to the universi All but Brown that is. The hearing will determine it. ty's faculty handbook, a Last month, university Brown's position with the Brown said that he has not tenured faculty member can, President E. A. Trabant an university and would ordinari resigned, as the university only be dismissed: claimed last month, and that nounced that Brown had ly make a recommendation to •for three reasons-- "tendered his resignation, ef the vice president for person ·he has no plans to do so in the incompetency, gross fective immediately . for nel and employee relations of future. negligence or moral turpitude. personal reasons" and a board fice. -

This Is What Democracy Sounds Like: Protest Performances of the Citizenship Movement in Wisconsin and Beyond

Social Movement Studies, 2015 Vol. 14, No. 6, 635–650, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2014.995077 This Is What Democracy Sounds Like: Protest Performances of the Citizenship Movement in Wisconsin and Beyond ANNA PARETSKAYA Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA ABSTRACT This article is a case study of an ongoing singing protest in Wisconsin, the group that calls itself Solidarity Sing Along (SSA). An offshoot of the 2011 Wisconsin Uprising, for the first 15 months of its existence SSA was an important nexus of local activists working to recall Republican state senators and the governor. After the recall’s failure the group not only continued to carry on but quite effortlessly reoriented its claim making and centered its protests on the freedom to assemble and petition the government, which had been an important cause from early on. Maintaining its pro-labor orientation, SSA has become part of a broader movement for democratic citizenship rights. Situating the group in musical practices of the Wisconsin protests and social movements more generally, I show that how SSA makes and performs its music makes it a part of the citizenship movement. This case study reveals a novel form of claim making within the repertoire of contention practiced by social movements: SSA is a ‘part-time occupation’ and as such has potential to be more resilient and durable than ‘permanent’ occupations a` la Occupy Wall Street. KEY WORDS: Protest music, labor movements, citizenship movements, Wisconsin Uprising, Occupy Wall Street, repertoires of contention The Wisconsin Uprising has long been over. -

The Ways of the Poem..Pdf

63-07910 821*08 M643w $32!? e'^ Miles, Josephine , 1911- The ways of the poem, Sngle- wood Cliffs, N.J.. PrenticP^ 8a .08 Hiles, Josephine, ^, The ways of the poem. CUffs, N.J., Prentice- ties) literature se f edited by Josephine Miles PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH * UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA N. Englewood Cliffs, J. Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1961 1961 PRENTICE-HALL, INC. ENGLEWOOD CLIFFS, N, J, This volume, with minor revisions, is a shorter version of The Poem by Josephine Miles 1959 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED IN ANY FORM, BY MIMEO GRAPH OR ANY OTHER MEANS, WITHOUT PER MISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHERS. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD No.: 61-13262 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 94630- C f^. To like a poem is often to want to talk about it, to learn more about it, to hear it over and think about what is heard. This book begins with the ways and terms of such hearing. Then it proceeds to an abundance of poems of all kinds, com posed from different points of view by a hundred poets of four centuries in England and America. Finally, it considers poets as well as poems and poetry, with the work of five poets in some ways wholly individual and in some ways representative of historical changes in thought and tone. This volume is a shorter version of The Poem by about 100 pages of poetry, but contains the work of as many poets, over as wide a range of type and time, as does the fuller form. -

WLIR Playlist

I believe this complete list of WLIR/WDRE songs originally appeared on this site, but the full playlist is no longer available. https://wlir.fm/ It now only has the list of “Screamers and Shrieks” of the week—these were songs voted on by listeners as the best new song of the week. I’ve included the chronological list of Screamers and Shrieks after the full alphabetical playlist by artist. 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Can't Ignore The Train 10,000 Maniacs Eat For Two 10,000 Maniacs Headstrong 10,000 Maniacs Hey Jack Kerouac 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Non-Live version) 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather (Live) 10,000 Maniacs Peace Train 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs What's The Matter Here 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 12 Drummers Drumming We'll Be The First Ones 2 NU This Is Ponderous 3D Nearer 4 Of Us Drag My Bad Name Down 9 Ways To Win Close To You 999 High Energy Plan 999 Homicide A Bigger Splash I Don’t Believe A Word (Innocent Bystanders) A Certain Ratio Life's A Scream A Flock Of Seagulls Heartbeat Like A Drum A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran A Flock Of Seagulls It's Not Me Talking A Flock Of Seagulls Living In Heaven A Flock Of Seagulls Never Again (The Dancer) A Flock Of Seagulls Nightmares A Flock Of Seagulls Space Age Love Song A Flock Of Seagulls Telecommunication A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls What Am I Supposed To Do A Flock Of Seagulls Who's That Girl A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing A Popular History Of Signs The Ladderjack