The Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District: a Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Researcher 37.3

TEXAS TRANSPORTATION A Publication of the Texas Transportation Institute • Member of The Texas A&M University System • Vol. 37 • No. 3 • 2001 ImprovingImproving WorkWork ZoneZone SafetySafety EnhancingEnhancing PedestrianPedestrian andand TransitTransit SafetySafety Cutting-EdgeCutting-Edge CrashCrash TestingTesting Center for Transportation Safety Texas legislature establishes safety center at TTI Over 300,000 traffic crashes occurred in Texas in 1999. More than 3,500 people died in those crashes and another 200,000 suffered injuries. Those losses are unacceptably large. To reduce these losses, a new center at the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) will focus on health and safety issues associated with transportation. The Governor signed legislation establishing the Center for Transportation Safety on June 13, 2001. Senate Bill 586, sponsored by Senator Steve Ogden, created the center, and the leg- islature appropriated $1 million to support the center in the coming biennium. “The center provides TTI with tremendous opportunities to address safety issues, and we are exploring a number of intriguing projects and partnerships,” says Dennis Christiansen, deputy director of TTI. “Work performed through the center will be closely coordinated with safety-related work being pursued by other agencies, such as the Texas Department of Transportation.” The center will conduct projects targeted to six main goals: Identifying and conducting research that will enhance transportation safety Providing educational opportunities for graduate-level and -

Kathy Ann Wilcox [email protected] 1541 Ranchview Lane Carrollton, TX 75007 (979)229-0781

Kathy Ann Wilcox [email protected] 1541 Ranchview Lane Carrollton, TX 75007 (979)229-0781 OBJECTIVE: To obtain a leadership position in which I can fully utilize my experience in underwriting, auditing, risk management, compliance, and working with people. PERSONAL: A highly motivated team player with a very strong work ethic in order to consistently innovate progressive success. EDUCATION: Texas A&M University, College Station, TX- Bachelor of Agricultural Development, emphasis Animal Science Degree- May 2003. Distinguished Student Award Aggie Representative Ambassador, Animal Science Department Eisenhower Leadership Development Program, The Bush School Alpha Zeta Honorary and Professional Fraternity of Agriculture Member Texas A&M Wool Judging Team Member Cattlewomen’s Club Member Saddle and Sirloin Club Member Sigma Alpha Agricultural Sorority Member SKILLS: Underwriting, Auditing, risk management, people and communication skills, expertise in analyzing various income documentation, personal and business financial statements, cash flows, income statements, paystubs, and tax returns. Strong analytical skills in reviewing credit reports, processing credit applications, surveys, legal descriptions, title work, appraisals, and worksheet data analysis. Experience in office management, supervising student workers, payment processing, records and retention, office policy and procedure. Knowledgeable in Excel 2007 vLookups, Microsoft Word, Outlook, Power Point, and all Bank of America underwriting software programs. EXPERIENCE: Bank of America Mortgage Retention Operations Quality Assurance Manager Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Servicing for Others- HAMP and Non-HAMP Modification Programs- March 2012 to present Managed a successful and large group of Retention Operation Quality Assurance Associates. Successfully communicated all GSE and Servicing for Others HAMP and Non-HAMP underwriting policy and procedures to a team of auditors. -

Brazos Valley Coordinated Transportation Plan Update

2017 Brazos Valley Coordinated Transportation Plan Update Approved by Independent Stakeholder Committee, February 15, 2017 BRAZOS VALLEY COORDINATED TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE Thank you This update of the 2017 Coordinated Transportation Plan was made possible by numerous stakeholders throughout the region. We would like to thank our staff and numerous stakeholders and active citizens for their participation in this plan. BVCOG Staff Navasota Cab & Courier Leon County Health Resource Michael Parks Rance Parham Center Travis Halm Donna Danford Clay Barnett Texas Veterans Commission Gloria McCarty Jeffrey English Troy Robie Monica Rainey Madison County Health Vietnam Veterans Association Resource Center Brazos Transit District Thomas Powell Towanda Webber Wendy Weedon Sarah Santoy Workforce Solutions – Jobs Calvert Senior Center Center & Childcare Bea Cephas Brazos Valley Center for Gaylen Lange Independent Living Robert Gonzales Washington County Healthy Jackie Pacha Living Association Andrew Morse Area Agency on Aging Toy Kurtz Troy Howell Ronnie Gipson Cyndy Belt Stephen Galvin City of Bryan Tracy Glass Lindsay Hackett Department of Assistive and Brazos Valley Area Agency on Rehabilitative Services Regional Citizens Aging Virginia Herrera Ann Boehm Ronnie Gipson Steven Galvin Texas A&M Health Science Center Bryan-College Station MPO Karla Blaine Daniel Rudge Debbie Muesse Brad McCaleb Elizabeth Gonzalez-Silva Bart Benthul Angela Alaniz Heart of Texas Regional Burleson County Health Advisory Council Resource Commission Gary Clouse Albert Ramirez Sherii Alexander Housing Voucher Program Karla Flanagan Grimes County Health Resource Center Workforce Solutions Brazos Betty Feldman Valley Lara Meece Patricia Buck Nancy Franek Shawna Rendon 1 BRAZOS VALLEY COORDINATED TRANSPORTATION PLAN UPDATE Contents Thank you ........................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................... -

Groundwater Conservation Districts * 1

Confirmed Groundwater Conservation Districts * 1. Bandera County River Authority & Groundwater District - 11/7/1989 2. Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer CD - 8/13/1987 DALLAM SHERMAN HANSFORD OCHILTREE LIPSCOMB 3. Bee GCD - 1/20/2001 60 4. Blanco-Pedernales GCD - 1/23/2001 5. Bluebonnet GCD - 11/5/2002 34 6. Brazoria County GCD - 11/8/2005 HARTLEY MOORE HUTCHINSON ROBERTS 7. Brazos Valley GCD - 11/5/2002 HEMPHILL 8. Brewster County GCD - 11/6/2001 9. Brush Country GCD - 11/3/2009 10. Calhoun County GCD - 11/4/2014 OLDHAM POTTER CARSON WHEELER 11. Central Texas GCD - 9/24/2005 63 GRAY Groundwater Conservation Districts 12. Clear Fork GCD - 11/5/2002 13. Clearwater UWCD - 8/21/1999 COLLINGSWORTH 14. Coastal Bend GCD - 11/6/2001 RANDALL 15. Coastal Plains GCD - 11/6/2001 DEAF SMITH ARMSTRONG DONLEY of 16. Coke County UWCD - 11/4/1986 55 17. Colorado County GCD - 11/6/2007 18. Comal Trinity GCD - 6/17/2015 Texas 19. Corpus Christi ASRCD - 6/17/2005 PARMER CASTRO SWISHER BRISCOE HALL CHILDRESS 20. Cow Creek GCD - 11/5/2002 21. Crockett County GCD - 1/26/1991 22. Culberson County GCD - 5/2/1998 HARDEMAN 23. Duval County GCD - 7/25/2009 HALE 24. Evergreen UWCD - 8/30/1965 BAILEY LAMB FLOYD MOTLEY WILBARGER 27 WICHITA FOARD 25. Fayette County GCD - 11/6/2001 36 COTTLE 26. Garza County UWCD - 11/5/1996 27. Gateway GCD - 5/3/2003 CLAY KNOX 74 MONTAGUE LAMAR RED RIVER CROSBY DICKENS BAYLOR COOKE 28. Glasscock GCD - 8/22/1981 COCHRAN HOCKLEY LUBBOCK KING ARCHER FANNIN 29. -

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2008

Texas Fact Book 2 0 0 8 L e g i s l a t i v e B u d g e t B o a r d LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2007 – 2008 DAVID DEWHURST, JOINT CHAIR Lieutenant Governor TOM CRADDICK, JOINT CHAIR Representative District 82, Midland Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo WARREN CHISUM Representative District 88, Pampa Chair, House Committee on Appropriations JAMES KEFFER Representative District 60, Eastland Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means FRED HILL Representative District 112, Richardson SYLVESTER TURNER Representative District 139, Houston JOHN O’Brien, Director COVER PHOTO COURTESY OF SENATE MEDIA CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE EIGHTIETH TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing . 21 Population . 21 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Technology . 23 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2008 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U .s . 26 Texas and the U .s . Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . -

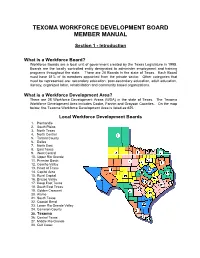

Texoma Workforce Development Board Member Manual

TEXOMA WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT BOARD MEMBER MANUAL Section 1 - Introduction What is a Workforce Board? Workforce Boards are a local unit of government created by the Texas Legislature in 1995. Boards are the locally controlled entity designated to administer employment and training programs throughout the state. There are 28 Boards in the state of Texas. Each Board must have 51% of its members appointed from the private sector. Other categories that must be represented are: secondary education, post-secondary education, adult education, literacy, organized labor, rehabilitation and community based organizations. What is a Workforce Development Area? There are 28 Workforce Development Areas (WDA) in the state of Texas. The Texoma Workforce Development Area includes Cooke, Fannin and Grayson Counties. On the map below, the Texoma Workforce Development Area is listed as #25. Local Workforce Development Boards 1. Panhandle 2. South Plains 3. North Texas 4. North Central 5. Tarrant County 6. Dallas 7. North East 8. East Texas 9. West Central 10. Upper Rio Grande 11. Permian Basin 12. Concho Valley 13. Heart of Texas 14. Capital Area 15. Rural Capital 16. Brazos Valley 17. Deep East Texas 18. South East Texas 19. Golden Crescent 20. Alamo 21. South Texas 22. Coastal Bend 23. Lower Rio Grande Valley 24. Cameron County 25. Texoma 26. Central Texas 27. Middle Rio Grande 28. Gulf Coast Who is a CEO? The CEOs are the Chief Elected Officials for each Board area. CEOs are defined in the legislation (HB 1863) that created Boards. For Texoma, the CEOs are the three county judges and the mayor of the largest city (Sherman). -

Soil Survey of Brazos County, Texas

United States In cooperation with Department of Texas Agricultural Agriculture Experiment Station and Soil Survey of Texas State Soil and Water Natural Conservation Board Brazos County, Resources Conservation Service Texas 3 How To Use This Soil Survey General Soil Map The general soil map, which is a color map, shows the survey area divided into groups of associated soils called general soil map units. This map is useful in planning the use and management of large areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the map, identify the name of the map unit in the area on the color-coded map legend, then refer to the section General Soil Map Units for a general description of the soils in your area. Detailed Soil Maps The detailed soil maps can be useful in planning the use and management of small areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the Index to Map Sheets. Note the number of the map sheet and turn to that sheet. Locate your area of interest on the map sheet. Note the map unit symbols that are in that area. Turn to the Contents, which lists the map units by symbol and name and shows the page where each map unit is described. The Contents shows which table has data on a specific land use for each detailed soil map unit. Also see the Contents for sections of this publication that may address your specific needs. 4 This soil survey is a publication of the National Cooperative Soil Survey, a joint effort of the United States Department of Agriculture and other Federal agencies, State agencies including the Agricultural Experiment Stations, and local agencies. -

Grimes County Health Services Directory

Grimes County Health Services Directory 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Emergency Numbers ............................................................................ 1 Police ............................................................................................. 1 Fire ................................................................................................ 1 Ambulance .................................................................................... 1 Sheriff’s Department ..................................................................... 1 Texas Highway Patrol ................................................................... 1 Other Emergency Numbers ................................................................. 2 Health Services ..................................................................................... 5 Ambulance/Emergency Medical Services ..................................... 5 Audiologists .................................................................................. 5 Chiropractors ................................................................................. 5 Counseling/Mental Health ............................................................. 5 Dentists .......................................................................................... 5 Diabetic Supplies .......................................................................... 6 DNA and Drug Testing ................................................................. 6 Fitness .......................................................................................... -

Anderson County UWCD 2007 Management Plan

ANDERSON COUNTY UNDERGROUND WATER CONSERVATION DISTRICT 2007-2012 Water Management Plan Adopted: July 12, 2007 450 ACR 409, Palestine, Texas 75803 903-729-8066 [email protected] Anderson County Underground Water Conservation District Water Management Plan 2007-2012 CREATION OF THE DISTRICT The Anderson County Underground Water Conservation District is created under the authority ofArticle XVI, Section 59, ofthe Texas Constitution by Senate Bill 1518 on May 15, 1989. RIGHTS, POWERS AND DUTIES OF THE DISTRICT The district was originally governed by Chapter 52, Texas Water Code, which was repealed by the 74th Legislature in 1995. The district is now governed by and subject to Chapter 36, Texas Water Code, and has all the powers, duties, authorities and responsibilities provided by Chapter 36, Texas Water Code. The district is also governed by the Texas Administrative Code: Title 31 Natural Resources and Conservation, Part 10 Texas Water Development Board, Chapter 356 Groundwater Management. 1. The district may prohibit the pumping or use ofgroundwater ifthe district determinesthat the pumpingwould present an unreasonable risk ofpollution. 2. The district may limit the pumping ofgroundwater to uses determined by the board to benefit the district. 3. The district may requirepersonsholdinga permit for an injectionwell to purchase water from the district. 4. The district may adopt regulationsfor the disposal ofsalt dome leachate in the district or may require disposal ofsalt dome leachate outside the district. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Qualifications To be qualified for election as a director, a person must be: 1. a resident ofthe district, 2. at least 18 years ofage; and 3. not otherwise disqualified by Section 50.026, Water Code Composition ofthe Board The board ofthe district is composed ofnine members. -

Policy Report Texas Fact Book 2006

Te x a s F a c t Book 2006 LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD SEVENTY-NINTH TEXAS LEGISLATURE 2005 – 2006 DAVID DEWHURST, CO-CHAIR Lieutenant Governor, Austin TOM CRADDICK, CO-CHAIR Representative District 82, Midland Speaker of the House of Representatives STEVE OGDEN Senatorial District 5, Bryan Chair, Senate Committee on Finance ROBERT DUNCAN Senatorial District 28, Lubbock JOHN WHITMIRE Senatorial District 15, Houston JUDITH ZAFFIRINI Senatorial District 21, Laredo JIM PITTS Representative District 10, Waxahachie Chair, House Committee on Appropriations JAMES KEFFER Representative District 60, Eastland Chair, House Committee on Ways and Means FRED HILL Representative District 112, Richardson VILMA LUNA Representative District 33, Corpus Christi JOHN O’BRIEN, Deputy Director CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT STATEWIDE ELECTED OFFICIALS . 1 MEMBERS OF THE SEVENTY-NINTH TEXAS LEGISLATURE . 3 The Senate . 3 The House of Representatives . 4 SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES . 8 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEES . 10 BASIC STEPS IN THE TEXAS LEGISLATIVE PROCESS . 14 TEXAS AT A GLANCE GOVERNORS OF TEXAS . 15 HOW TEXAS RANKS Agriculture . 17 Crime and Law Enforcement . 17 Defense . 18 Economy . 18 Education . 18 Employment and Labor . 19 Environment and Energy . 19 Federal Government Finance . 20 Geography . 20 Health . 20 Housing. 21 Population . 21 Social Welfare . 22 State and Local Government Finance . 22 Technology . 23 Transportation . 23 Border Facts . 24 STATE HOLIDAYS, 2006 . 25 STATE SYMBOLS . 25 POPULATION Texas Population Compared with the U.S. 26 Texas and the U.S. Annual Population Growth Rates . 27 Resident Population, 15 Most Populous States . 28 Percentage Change in Population, 15 Most Populous States . 28 Texas Resident Population, by Age Group . -

MUNICIPAL POLICY SUMMIT H August 23-24, 2018 Hilton Austin 500 East Fourth Street Austin, Texas H Summit Delegates

TEXAS MUNICIPAL LEAGUE MUNICIPAL POLICY SUMMIT H August 23-24, 2018 Hilton Austin 500 East Fourth Street Austin, Texas H Summit Delegates Texas Municipal League Municipal Policy Summit Chair: Julie Masters, Mayor, Dickinson Co Vice-Chair: Kathryn Wilemon, Mayor Pro Tem, Arlington Co Vice-Chair: Anthony Williams, Mayor, Abilene TML Board Representative: Ramiro Rodriguez, Mayor, Palmhurst Jerry Bark, Director Parks and Recreation, Harker Heights Allen Barnes, City Administrator, Stephenville John Basham, Mayor Pro Tem, Reno Alan Bojorquez, City Attorney, Bastrop Jeffrey Boney, Councilmember, Missouri City Shelley Brophy, Mayor, Nacogdoches Cindy Burchfield, Councilmember, Daisetta Lynn Buxkemper, Mayor Pro Tem, Slaton Scott Campbell, City Manager, Roanoke Dawn Capra, Mayor, Johnson City Sylvia Carrillo-Trevino, Assistant City Manager, Corpus Christi Jesse Casey, Mayor, Hallsville Randy Childers, Building Official, Waco Roxann Pais Cotroneo, City Attorney, Three Rivers Drew Corn, Town Administrator, Northlake Jason Cozza, City Administrator, Hallettsville Jim Darling, Mayor, McAllen Kevin Falconer, Mayor, Carrollton Paul Frederiksen, Assistant City Manager, Duncanville Brian Frieda, Chief of Police, Sweetwater George Fuller, Mayor, McKinney Beverly Gaines, Councilmember, Webster Himesh Gandhi, Councilmember, Sugar Land Andrea Gardner, City Manager, Watauga Teclo Garica, Director of Strategic Partnerships & Program Development, Mission Gregg Geesa, Councilmember, White Settlement Reed Greer, Mayor, Melissa Tom Hart, City Manager, Grand Prairie -

Texas Continuum of Care Regions 2018

Dallam Sherman Hansford Ochiltree Lipscomb Texas Hartley Moore Hutchinson Roberts Hemphill Oldham Potter Carson Gray Wheeler Continuum of Care Collings- Deaf Smith Randall Armstrong Donley worth Childress Regions Parmer Castro Swisher Briscoe Hall Hardeman Bailey Lamb Hale Floyd Motley Cottle 2018 Foard Wilbarger Wichita Clay Montague Lamar Red River Cochran Hockley Lubbock Crosby Dickens King Knox Baylor Archer Cooke Grayson Fannin Delta Bowie Franklin Morris Throck- Jack Wise Denton Titus Yoakum Terry Lynn Garza Kent Stonewall Young Collin Hopkins Haskell morton Hunt Cass Camp Rockwall Rains Marion Shackel- Parker Tarrant Dallas Wood Upshur Gaines Scurry Jones Stephens Palo Pinto Dawson Borden Fisher ford Kaufman Harrison Gregg Van Zandt Hood Johnson Ellis Smith Martin Mitchell Eastland Andrews Howard Nolan Taylor Callahan Erath Somervell Henderson Panola Rusk Hill Navarro Comanche Bosque Cherokee El Paso Loving Winkler Ector Midland Glasscock Sterling Coke Runnels Coleman Anderson Brown Shelby Hamilton Freestone Nacogdoches McLennan Ward Mills San Limestone Augustine Hudspeth Culberson Crane Tom Coryell Upton Reagan Green Concho Houston Reeves Irion Falls Leon Angelina Sabine McCulloch Lampasas San Saba Trinity Bell Newton Robertson Madison Jasper Schleicher Menard Burnet Polk Pecos Milam Walker Tyler Jeff Davis Mason Brazos Llano Williamson Grimes San Crockett Burleson Jacinto Sutton Kimble Gillespie Travis Lee Montgomery Hardin Blanco Terrell Washington Orange Bastrop Kerr Hays Waller Liberty Presidio Val Verde Edwards Kendall Austin