The Mattel Affairs: Dealing in the Complexity of Extended Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FAQ & Troubleshooting Settings

FAQ & Troubleshooting Settings Issue: Controller volume is too loud or quiet The controller may be set to volume level that is too loud or quiet. You can increase or decrease the volume in the system settings menu. Press the ο button, then use the steering stick to toggle left and right through the settings. When you reach “speaker volume,” press the check button to enter. Toggle left and right to adjust the controller volume from 1 to 5, then press the check button to confirm. Issue: I want to mute the engine sounds Press the ο button, then use the steering stick to toggle left and right through the settings. When you reach “engine sounds,” press the check button to enter. Toggle left and right to turn engine sounds on and off, then press the check button to confirm. Issue: The controller is not speaking the language I require The incorrect language was selected at startup. Switch on the controller while holding down the X button to reset. Will the Hot Wheels AI system interfere with my home Wi-Fi if it’s also 2.4GHz? Our code is designed to behave in much the same way as a wireless router does. The controller will scan for unused channels in the 2.4 GHz range (there are lots of them), and select a free one to use. It works perfectly, without you even noticing. Do I need to be connected to a Wi-Fi network to play with Hot Wheels AI? No. Hot Wheels AI creates its own connections between cars and controllers. -

2020 Christmas Store Card Back3

DONATiONS NEEDED BABiES Blankets, activity center/ baby gym, sleepers, crib toys, clothes and bibs, crib mobiles, car seat toys 1-3 YEAR OLDS Large trucks and cars, baby dolls (all ethnicities), doll accessories (bottles, etc), sensory books, musical toys, building blocks, soft dolls, Little Tykes items, Little People items, Fisher-Price toys, educational toys, stuffed animals 4-5 YEAR OLDS Board games for young children, Lincoln Logs, Tinkertoys, doll house with accessories, Hot Wheels tracks and cars, stuffed animals, wooden train sets, Nerf balls, plastic tool sets, art supplies, musical instruments, kitchen play sets, children’s books, dolls and accessories, Play-Doh, plastic animals, Tonka-type cars, and trucks, puzzles 1ST-3RD GRADERS Barbie dolls (all ethnicities), Barbie doll accessories, action figures, traditional board games, card games (i.e. Uno, Skip-bo, etc), art supplies and sets, Beanie Babies, baby dolls and accessories, 18” dolls and accessories (i.e. American Girl Doll-size), hand-held games (non-violent), children’s books, Polly Pocket / Polly Fashion sets, remote control vehicles (w/ batteries), Hot Wheels cars and track, basketballs (intermediate 28.5), footballs (youth size), soccer balls (size 4 or 5), cooking sets 4TH-6TH GRADERS Remote control vehicles, baseball, bat and glove, basketballs (28.5 & 29.5), footballs, soccer balls (size 5), sports equipment, Legos, jewelry, DVD players, brain teasers / puzzle mania, chapter books, art supplies, craft kits TEENAGERS DVD players, makeup, body glitter, etc., cologne gift sets, sports equipment (full size), jewelry, purses, gift sets (bath, hair, nails), hoodies, iPods, headphones / earbuds, art supplies (pencils, drawing pads), remote control vehicles (w/ batteries), Xbox, PlayStation, Wii games (non-violent), wallets, winter hats, scarves, fun socks RiDiNG TOYS (NEW ONLY) Tricycles, bicycles (all sizes), preschool riding toys, scooters, ripsticks, skateboards, longboards, skates, helmets (all sizes) $15 Walmart Gift Cards CHRiSTMAS STORE VOLUNTEERS NEEDED BiRCHMAN.ORG. -

Eyeclops Bionic Eye From

2007: the year in review THE “TOYING OF TECHNOLOGY” FocusingFocusing In:In: TheThe EyeClopsEyeClops®® BionicBionic EyeEye TakeTake itit toto thethe WebWeb GetGet MovingMoving THE YEAR OF HANNAH MONTANA® TOYS MICROECONOMICS ALSO IN TOYLAND TRENDTREND ALERT:ALERT: WHOWHO DOESN’TDOESN’T LOVELOVE CUPCAKES?CUPCAKES? AR 2007 $PRICELESS AR 2007 TABLE of CONTENTS JAKKS’ 4Girl POWER! In 2007 Disney® “It Girl” Miley Cyrus, a.k.a. Hannah Montana, hit the scene, and JAKKS was right there with her to catch the craze. Tween girls weren’t the only ones who took notice of the teen phenom. Hannah Montana toys from JAKKS were nominated for “Girls Toy of the Year” by the Toy Industry Association, received a 2008 LIMA licensing excellence award, and numerous retailers and media outlets also chose them as their top holiday picks for 2007. WIRED: SPOTLIGHT 6 on TECHNOLOGY From video game controllers to scientific magnifiers – in 2007 JAKKS expanded on its award-winning Plug It In & Play TV Games™ technology and created the EyeClops Bionic Eye, an innovative, handheld version of a traditional microscope for today’s savvy kids. JAKKS continued to amaze BOYS the action figure community will be by shipping more than 500 unique WWE® and BOYS Pokémon® figures to 8 retailers in more than 60 countries around the world in 2007. Joining the JAKKS powerhouse male action portfolio for 2008 and 2009 are The Chronicles of Narnia™: Prince Caspian™, American Gladiators®, NASCAR® and UFC Ultimate Fighting Championship® product lines, and in 2010… TNA® Total Non-Stop Action Wrestling™ toys. W e Hop e You E the Ne njoy w Ma gazine Format! - th 6 e editor 2007 ANNUAL REPORT THIS BOOK WAS PRINTED WITH THE EARTH IN MIND 2 JAKKS Pacifi c is committed to being a philanthropic and socially responsible corporate citizen. -

2011 Annual Report

Mattel Annual Report 2011 Click to play! Please visit: www.Mattel.com/AnnualReport The imagination of children inspires our innovation. Annual Report 2011 80706_MTL_AR11_Cover.indd 1 3/7/12 5:34 PM Each and every year, Mattel’s product line-up encompasses some of the most original and creative toy ideas in the world. These ideas have been winning the hearts of children, the trust of parents and the recognition of peers for more than 65 years. 80706_MTL_AR11_Text.indd 2 3/7/12 8:44 PPMM To Our Shareholders: am excited to be Mattel’s sixth environment. The year proved Chief Executive Offi cer in 67 to be a transition period for years, and honored to continue Fisher-Price with the expiration the legacy of such visionaries of the Sesame Street license as Mattel founders Ruth and and our strategic re-positioning Elliot Handler; Herman Fisher of the brand. and Irving Price, the name- sakes of Fisher-Price; Pleasant We managed our business Rowland, founder of American accordingly as these challenges Girl; and Reverend W. V. Awdry, played out during the year. We creator of Thomas & Friends®. maintained momentum in our core brands, such as Barbie®, First and foremost, I would like Hot Wheels®, American Girl® to acknowledge and thank and our new brand franchise, Bob Eckert for his tremendous Monster High®, as well as with contributions to the company key entertainment properties, during the last decade. Bob is such as Disney Princess® and a great business partner, friend CARS 2®. As a result, 2011 and mentor, and I am fortunate marks our third consecutive to still be working closely with year of solid performance: him as he remains Chairman revenues and operating of the Board. -

2012 Annual Report 2012 Annual Annual Report

Mattel 2012 Annual Report Annual Report Click to play! Please visit: corporate.mattel.com 42837_Cover.indd 1 3/13/13 9:59 AM 42837_Cover.indd 2 3/13/3/13/1313 99:59:59 AM 42837_Guts.indd 1 Nurture StructureStruct Plan Innovate 3/12/13 9:17 2012 Annual ReportReport corporate.mattel.com 1 AM To Our Shareholders: I am writing this letter having just completed one of my were well represented in their toy, video and consumer product busiest months as CEO. February 2013 started with our purchases. This, in turn, pleased fourth quarter and full-year 2012 earnings call, which our retail partners and allowed us to deliver solid results. was quickly followed by a formal presentation to the fi nancial analyst community during New York Toy Fair In 2012, we had record sales, eclipsing $7 billion in total gross sales for and an extensive series of meetings with many of our the fi rst time. Additionally, we grew investors across the country. NPD share in both the U.S. and the Euro51. It also marked the fourth I ended the month meeting with my straight year where we had strong senior management team to discuss gross margins and tight cost our future goals and how we can management, which drove expansion best achieve them. of our adjusted operating margins. All of these achievements resulted In short, February gave me great in adjusted EPS growth of 13%2, perspective on how our consumers, and our second consecutive year customers and owners are viewing of generating more than $1 billion our business. -

Sensory Play the Mattel Way!

Sensory Play The Mattel Way! ©2020 Mattel Beach Day Race in a Box Extra shipping boxes? Upcycle your shipping boxes and give your Hot Wheels a beach day (from home)! Pour some play sand in a cardboard box, add some Hot Wheels and race track to give your cars the ultimate beach day race adventure! ©2020 Mattel Monster Trucks in Dirt Trucks are meant to get dirty! There is nothing better then playing in the dirt with your Hot Wheels Monster Trucks. Build a dirt arena, fill some of the areas with water, add a couple Hot Wheels for the Monster Trucks to smash and enjoy a messy adventure! ©2020 Mattel Dinosaur Escape Kids love slime...and dinosaurs! Pour some of your Jurassic World Dinosaurs in a bucket, plastic bin, or deep bowl. Then add your Ooblek! To create ooblek, add 2 parts of corn starch and 1 part of water and mix. You can even add food coloring to make it colorful! This will create a fun sticky texture that’s fun to play with. Can you help your Jurassic Dinosaurs escape the Ooblek? ©2020 Mattel Matchbox Car Wash Just add bubbles! Are your Matchbox cars dusty and dirty? It’s easy to give them a car wash! Fill the sink or bathtub with water and don’t forget to add the bubbles! Use a toothbrush, sponge, or washcloth to give all your Matchbox cars a good scrub! Don’t forget to dry them off to see them shine. ©2020 Mattel Barbie Sensory Bag The perfect accessory! Create fun sensory bags filled with colored water and toys for your little one to squish and squeeze without the mess! Go on a hunt to find all your favorite Barbie accessories and shoes and place them in a Ziploc bag. -

Discontinue Use of Toys Immediately

IMPORTANT VOLUNTARY PRODUCT RECALL INFORMATION One product recalled for impermissible levels of lead November 2006 magnet recall expanded DISCONTINUE USE OF TOYS IMMEDIATELY Thank you for responding to the voluntary product recall by Mattel® (NZ). Please note, the affected “CARS” die-cast vehicle assortment line was manufactured between March 2007 and July 2007. The toy in question is a green army vehicle known as “Sarge”. The affected car may have been sold alone or as part of an assortment containing Sarge cars. Surface paints on the car may contain increased levels of lead, which if ingested, may have health ramifications. The recalled car is marked on the bottom with ‘7EA’. Sarge Cars or Assortments containing Sarge Cars have the following Model Numbers on the package: H6414, M1253 or L6294. The affected products are marked “China”. There have been no reports of injuries involving the affected product in New Zealand or overseas. Additionally, Mattel® is voluntarily recalling magnetic toys manufactured between January 2002 and January 31, 2007 including certain dolls, figures, play sets and accessories that may release small, powerful magnets. The recall expands upon Mattel®’s voluntary recall of eight toys in November 2006 and is based on a thorough internal review of all Mattel® brands. Mattel® is exercising caution and has expanded the list of recalled magnetic toys due to potential safety risks associated with toys that might contain loose magnets. Beginning in January 2007, Mattel® implemented enhanced magnet retention systems in its toys across all brands. Consumers should immediately take the recalled toys away from children. Please review the following images and descriptions affected by these recalls, indicating the total number of toys you own in the space next to the image. -

American Girl Unveils Truly Me™ Doll Line and Helps Girls Explore and Discover Who They Truly Are

May 21, 2015 American Girl Unveils Truly Me™ Doll Line and Helps Girls Explore and Discover Who They Truly Are —New, Exclusive Content and Innovative Retail Experience Encourages Self-Expression— MIDDLETON, Wis.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Starting today, girls will have the opportunity to explore and discover their own unique styles and interests with Truly Me, American Girl's newly-rebranded line of contemporary 18-inch dolls and accessories, girls' clothing, and exclusive play-based content. Truly Me, formerly known as My American Girl, allows a girl to create a one-of-a- kind friend through a variety of personalized doll options, including 40 different combinations of eye color, hair color and style, and skin color, as well as an array of outfits and accessories. To further inspire girls' creativity and self-expression, each Truly Me doll now comes with a Me-and-My Doll Activity Set, featuring over four dozen creative ideas for girls to do with their dolls, and an all-new Truly Me digital play experience that's free and accessible to girls who visit www.americangirl.com/play. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150521005102/en/ The new Truly Me microsite features a "Fun-spiration" section that's refreshed daily with interactive crafts, doll activities, quizzes, games, and recipes. There are also sections dedicated to Pets, Quizzes, and Do-It- Yourself videos, plus a Fan Gallery to submit favorite girl-and-doll moments or finished crafts projects. The Truly Me world will also include a downloadable Friendship Ties App that lets girls make virtual friendship bracelets to save and share, as well as a line of new Truly Me activity books—Friends Forever, School Spirit, and Shine Bright— designed to encourage self-esteem through self-expression. -

DOLL HOSPITAL ADMISSION FORM HOSPITAL Where Your American Girl Doll Goes to Get Better! ® Please Allow Two to Four Weeks for Repair

® DOLL DOLL HOSPITAL ADMISSION FORM HOSPITAL Where your American Girl doll goes to get better! ® Please allow two to four weeks for repair. To learn more about our Doll Hospital, visit americangirl.com. Date / / Name of doll’s owner We’re admitting Hair color Eye color (Doll’s name) All repairs include complimentary wellness service. After repairs, dolls are returned with: For 18" dolls—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Socks • Doll Hospital ID Bracelet • Get Well Card WI 53562 eton, For Bitty Baby™/Bitty Twins™ dolls—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Cap • Get Well Card For WellieWishers™—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Socks • Get Well Card DOLL HOSPITAL A la carte services for ear piercing/hearing aid installation excludes wellness service and other items included with repairs. Place Fairway 8350 Middl Type of repair/service: Admission form 18" AMERICAN GIRL DOLLS Total price Bill to: USD: method. a traceable via the hospital doll to your REPAIRS Adult name Clip and tape the mailing label to your package to send send to package your to the mailing label Clip and tape Send to: New head (same American Girl only) $44 Address New body (torso and limbs) $44 New torso limbs (choose one) $34 Apt/suite Eye replacement (same eye color only) $28 City Doll Hospital Admission Process Reattachment of head limbs (choose one) $32 Place your undressed doll and admission form Wellness visit $28 State Zip Code Skin cleaned, hair brushed, hospital gown, with payment attached, including shipping and certificate, but no “major surgery” † charges, in a sturdy box. -

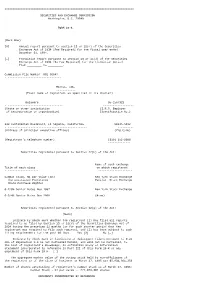

Page 1 of 2) COMPUTATION of INCOME PER COMMON and COMMON EQUIVALENT SHARE ------(In Thousands, Except Per Share Amounts)

================================================================================ SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) [X] Annual report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [Fee Required] for the fiscal year ended December 31, 1994. [_] Transition report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [No Fee Required] for the transition period from _________ to _________. Commission File Number 001-05647 - --------------------------------- MATTEL, INC. ------------ (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 95-1567322 - ---------------------------------- ------------------- (State or other jurisdiction (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 333 Continental Boulevard, El Segundo, California 90245-5012 - ------------------------------------------------- ---------- (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (Registrant's telephone number) (310) 252-2000 -------------- Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered - ------------------- --------------------- Common stock, $1 par value (and New York Stock Exchange the associated Preference Pacific Stock Exchange Share Purchase Rights) 6-7/8% Senior Notes Due 1997 New York Stock Exchange 6-3/4% Senior Notes Due 2000 (None) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: (None) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

A Boneca Barbie: Relações Entre Design Do Produto, Representação Do Feminino E Significação

XII Semana de Extensão, Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação - SEPesq Centro Universitário Ritter dos Reis A boneca Barbie: relações entre design do produto, representação do feminino e significação Laura Felhauer Toledo Mestranda em Design Centro Universitário Ritter dos Reis - Uniritter [email protected] Suelen Rizzi Mestranda em Design Centro Universitário Ritter dos Reis - Uniritter [email protected] César Steffen Doutor em Comunicação Social Centro Universitário Ritter dos Reis - Uniritter [email protected] Resumo: O artigo tem por objetivo apresentar um breve histórico da boneca Barbie levando em consideração o contexto social e as alterações realizadas no design do produto. Para tal, foi realizada uma pesquisa desde o surgimento da boneca Barbie em 1959, idealizada por Ruth Handler após conhecer a boneca “Bild Lili” em uma viagem a Alemanha e lançada pela Mattel- empresa criada por ela e o marido- chegando até a contemporaneidade, onde é possível encontrar diversos modelos de Barbies, pois a boneca passou por modificações nas formas corporais e estéticas. Primeiramente foram feitas pequenas alterações na forma e na mobilidade, depois foram acrescentadas opções de bonecas oriundas de outras etnias, modificando o tom da pele e cabelo e alguns traços faciais. Em 2016 foi lançada a coleção “Barbie Fashionistas 2016”, na qual a Mattel introduz três novos tipos de corpo – “Tall”, “Curvy” e “Petite”. Para entender como as mudanças formais e estéticas do produto podem ter diferentes significações para as crianças, foi necessário relacionar o histórico da boneca com o contexto de cada momento. Pretende-se mostrar a evolução no design dos corpos das bonecas Barbie ao longo dos anos, evidenciando suas principais diferenças e mudanças, com a finalidade de entender as significações que essas alterações podem gerar.