Here They Have Been Most Felt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euroopa Parlamendi Arutelud 1

18-11-2008 ET Euroopa Parlamendi arutelud 1 TEISIPÄEV, 18. NOVEMBER 2008 ISTUNGI JUHATAJA: Luisa MORGANTINI asepresident 1. Osaistungjärgu avamine (Istung avati kell 9.00.) 2. Inimõiguste, demokraatia ja õigusriigi põhimõtete rikkumise juhtumite arutamine (esitatud resolutsiooni ettepanekute tutvustamine) (vt protokoll) 3. Otsus kiirmenetluse kohta Ettepanek võtta vastu nõukogu määrus, millega muudetakse nõukogu määrust (EÜ) nr 332/2002, millega liikmesriikide maksebilansi toetamiseks luuakse keskmise tähtajaga rahalise abi süsteem (KOM(2008)0717 – C6-0389/2008 – 2008/0208(CNS)) Pervenche Berès, majandus- ja rahanduskomisjoni esimees. – (FR) Proua juhataja, kõnealune arutelu toimub täna õhtul juhul, kui täiskogu hääletab kõnealust küsimust käsitleva kiirmenetluse poolt. See on Euroopa õigusakti muudatusettepanek, mis võimaldab meil tagada maksebilansi süsteemid väljaspool euroala asuvatele riikidele. Nagu me kõik teame, on tegemist Ungari küsimusega, kuid kahjuks ma usun, et me peame ettepoole vaatama ja seega edendama seda Euroopa Liidu süsteemi, et anda abi ELi, sealhulgas euroalast väljaspool asuvatele, liikmesriikidele. Seepärast palun ma täiskogul hääletada kõnealuse kiirmenetluse poolt. (Kiirmenetluse taotlus kiideti heaks)(1) 4. Ühise põllumajanduspoliitika raames põllumajandustootjate suhtes kohaldatavad otsetoetus- ja teatavad muud toetuskavad – Ühise põllumajanduspoliitika muudatused – Maaelu Arengu Euroopa Põllumajandusfondist antavad maaelu arengu toetused –Ühenduse maaelu arengu strateegiasuunised (2007–2013) (arutelu) Juhataja. -

Malala Yousafzai Documentary James Mcavoy Holds the Award for Best British Film

SUBSCRIPTION TUESDAY, MARCH 31, 2015 JAMADA ALTHANI 11, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Panel to Morocco Ancient Petra India’s women discuss diesel confronts sees few athletes box, smuggling abortion taboo visitors as Jordan shoot, wrestle with officials3 with reform7 tourism40 declines for17 recognition Ban names Amir ‘Global Min 22º Max 31º Humanitarian Champion’ High Tide 10:15 & 21:35 Low Tide UN chief hails Sheikh Sabah’s compassion, generosity 03:15 & 15:40 40 PAGES NO: 16476 150 FILS NEW YORK: UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon hoped world leaders emulate HH the Amir of Kuwait Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah’s humanitarian lead- NGOs pledge $506m for Syrian refugees ership, describing him as a “Global Humanitarian Champion”. In an exclusive interview with Kuwait News KUWAIT: A UN envoy warned yesterday of a “horrify- Agency (KUNA) and Kuwait TV, Ban expressed his deep- ing” humanitarian situation brewing in Syria as non- est appreciation of HH the Amir for his generous and governmental organizations pledged more than $500 compassionate leadership in hosting the third interna- million for refugees on the eve of a major donor con- tional donors conference (Kuwait III) for Syria. ference. The United Nations has launched an appeal Ban, noting the Syrian people’s dire need of to raise $8.4 billion for Syria this year and hopes to resources of all kinds, called on the world leaders to receive major pledges at the donor meeting today in take part in this pledging conference. With the estima- Kuwait. “Failing to meet the required funds risks tion of $8.4 billion set by the UN needed to address the resulting in a horrifying and dangerous humanitarian current humanitarian crisis in 2015-16, Ban said $2.9 bil- catastrophe,” Abdullah Al-Maatouq, UN special envoy lion is for the Syrian response plan and $5.5 billion is for humanitarian affairs, told a meeting of NGOs. -

Report 2021, No. 6

News Agency on Conservative Europe Report 2021, No. 6. Report on conservative and right wing Europe 20th March, 2021 GERMANY 1. jungefreiheit.de (translated, original by jungefreiheit.de, 18.03.2021) "New German media makers" Migrant organization calls for more “diversity” among journalists media BERLIN. The migrant organization “New German Media Makers” (NdM) has reiterated its demand that editorial offices should become “more diverse”. To this end, the association presented a “Diversity Guide” on Wednesday under the title “How German Media Create More Diversity”. According to excerpts on the NdM website, it says, among other things: “German society has changed, it has become more colorful. That should be reflected in the reporting. ”The manual explains which terms journalists should and should not use in which context. 2 When reporting on criminal offenses, “the prejudice still prevails that refugees or people with an international history are more likely to commit criminal offenses than biographically Germans and that their origin is causally related to it”. Collect "diversity data" and introduce "soft quotas" Especially now, when the media are losing sales, there is a crisis of confidence and more competition, “diversity” is important. "More diversity brings new target groups, new customers and, above all, better, more successful journalism." The more “diverse” editorial offices are, the more it is possible “to take up issues of society without prejudice”, the published excerpts continue to say. “And just as we can no longer imagine a purely male editorial office today, we should also no longer be able to imagine white editorial offices. Precisely because of the special constitutional mandate of the media, the question of fair access and the representation of all population groups in journalism is also a question of democracy. -

Parlament Ewropew

23.12.2009 MT Il-Ġurnal Uffiċjali tal-Unjoni Ewropea C 316 /1 http://www.europarl.europa.eu/QP-WEB IV (Informazzjoni) INFORMAZZJONI MINN ISTITUZZJONIJIET U KORPI TAL-UNJONI EWROPEA Parlament Ewropew MISTOQSIJIET BIL-MIKTUB BIT-TWEĠIBIET Lista tat-titli tal-Mistoqsijiet bil-Miktub imressqa mill-Membri fil-Parlament Ewropew, b'indikazzjoni tan-numru u tal-lingwa oriġinali tal-mistoqsija, tal-awtur tagħha u tal-grupp politiku tiegħu, tal-istituzzjoni destinatarja, kif ukoll tad-data tat-tressiq u tas-suġġett tal-mistoqsija. (2009/C316/01) E-3028/08 (ES) minn Willy Meyer Pleite (GUE/NGL) lill-Kummissjoni (27 ta' Mejju 2008) Suġġett: Il-ksur tad-Direttiva dwar it-trattament tal-ilma għar-rimi fl-estwarju ta’ O Burgo, Galicia, Spanja TweġiBa preliminarja mill-Kummissjoni (23 ta' Lulju 2008) TweġiBa konġunta mill-Kummissjoni (4 ta' Marzu 2009) P-4422/08 (EN) minn Inese Vaidere (UEN) lill-Kummissjoni (30 ta' Lulju 2008) Suġġett: Pjanijiet min-naħa tar-Russja li titneħħa s-sistema tal-viżi għal ċerti ċittadini tal-Unjoni Ewropea li għandhom nazzjonalità Russa TweġiBa mill-Kummissjoni (8 ta' SettemBru 2008) E-4679/08 (NL) minn Jeanine Hennis-Plasschaert (ALDE) lill-Kummissjoni (3 ta' SettemBru 2008) Suġġett: L-immaniġġjar tal-konfini esterni tal-Komunità u tat-Turkija – is-soluzzjoni għal dan l-intopp TweġiBa mill-Kummissjoni (29 ta' OttuBru 2008) E-4911/08 (EN) minn Caroline Jackson (PPE-DE) lill-Kummissjoni (17 ta' SettemBru 2008) Suġġett: ProBlema tas-saħħa TweġiBa mill-Kummissjoni (27 ta' OttuBru 2008) P-5000/08 (DE) minn Vural Öger (PSE) lill-Kummissjoni -

A Guide to the New Commission

A guide to the new Commission allenovery.com 2 A guide to the new Commission © Allen & Overy LLP 2019 3 A guide to the new Commission On 10 September, Commission President-elect Ursula von der Leyen announced the new European Commission. There were scarcely any leaks in advance about the structure of the new Commission and the allocation of dossiers which indicates that the new Commission President-elect will run a very tight ship. All the Commission candidates will need approval from the European Parliament in formal hearings before they can take up their posts on 1 November. Von der Leyen herself won confirmation in July and the Spanish Commissioner Josep Borrell had already been confirmed as High Representative of the Union for Foreign Policy and Security Policy. The new College of Commissioners will have eight Vice-Presidents technological innovation and the taxation of digital companies. and of these three will be Executive Vice-Presidents with supercharged The title Mrs Vestager has been given in the President-elect’s mission portfolios with responsibility for core topics of the Commission’s letter is ‘Executive Vice-President for a Europe fit for the Digital Age’. agenda. Frans Timmermans (Netherlands) and Margrethe Vestager The fact that Mrs Vestager has already headed the Competition (Denmark), who are incumbent Commissioners and who were both portfolio in the Juncker Commission combined with her enhanced candidates for the Presidency, were rewarded with major portfolios. role as Executive Vice-President for Digital means that she will be Frans Timmermans, who was a Vice-President and Mr Junker’s a powerful force in the new Commission and on the world stage. -

The New European Commission – What Happens Next?

THE NEW EUROPEAN COMMISSION – WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? The new European Commission is taking shape, following last week’s announcement of the full line-up of new Commissioners and their portfolios. President-elect Ursula von der Leyen has achieved the gender parity she sought, with 13 of the 27 Commission posts taken by women. The portfolios have been carefully allocated, taking into account the previous experience of the nominees, as well as the size and relative influence of each Member State. The Commissioners-designate will now be vetted by the European Parliament Committees before a plenary vote on the full college of Commissioners next month. The hearings are an opportunity for MEPs to win political points and media attention. Given the frustration over the rejection of the Spitzenkandidat process, we can expect the Parliament to assert itself during the vetting process through threatening to withhold its approval from poorly performing nominees. As von der Leyen will be eager to ensure a straightforward vote in plenary, she is likely to listen seriously to the Parliament’s concerns. Below we set out what to expect from the hearing process and key dates ahead of the new Commission taking office on 1 November. TIMELINE: 30 SEPT - 8 OCT Hearings of Commissioners-designate. 19 SEPTEMBER October 2: Didier Reynders (Justice) and 23 OCTOBER 1 NOVEMBER Decision on which Committee Sylvie Goulard (Internal Market); European Parliament plenary New Commission takes office. will interrogate each nominee; October 3: Margaritis Schinas (VP - vote on the full College of European way of life); October 8: Margrethe Committees issue written questions Vestager (VP – tech and digital), Valdis Commissioners. -

The Eu's New Commission: Digital Policy in the Limelight

Policy Papers and Briefs - 13, 2019 THE EU’S NEW COMMISSION: DIGITAL POLICY IN THE LIMELIGHT Stephanie Borg Psaila Summary • The work of the new European Commission (EC) offi- • The EC President also wants to see a more balanced cially started in December 2019. Leading the work approach to how data is used: allowing the flow and use is a set of political guidelines issued by incoming EC of data for the benefit of innovation and market growth, President Ursula von der Leyen, focusing on climate, while adhering to strong privacy, security, and ethical technology, and demography. standards. • In relation to technology and digital policy, there are ten • Across other key areas, the EC President plans to make key areas of relevance, including artificial intelligence Europe a tech sovereign by taking the lead in stand- (AI) and data, which the EC President sees as the key ard-setting, and investing in the tech industry. ingredients that can help solve societal problems. • Although the guidelines will be the EC’s compass for the • Among the most anticipated policy measures is one that next five years, the implications go beyond European relates to AI: ‘In my first 100 days in office, I will put -for shores. ward legislation for a coordinated European approach on the human and ethical implications of AI.’ December 2019 Introduction: The Commission’s digital policy priorities for the next five years The work of the new European Commission (EC) officially including artificial intelligence (AI) and data, which she started in December, after a delay in vetting procedures sees as the key ingredients that can help solve soci- (and partially due to Brexit). -

Athens, 4 June 2021 Our Ref (Conf):135 Margaritis Schinas Vice-President of the European Commission Ylva Johansson European Commissioner for Home Affairs

HELLENIC REPUBLIC Ministry of Migration & Asylum The Minister Athens, 4 June 2021 Our ref (conf):135 Margaritis Schinas Vice-President of the European Commission Ylva Johansson European Commissioner for Home Affairs Copies to: Horst Seehofer Federal Minister of the Interior, Building and Community Federal Republic of Germany Gérald Darmanin Minister of Home Affairs French Republic Sammy Mahdi State Secretary for Asylum & Migration Kingdom of Belgium Jean Asselborn Minister for Foreign & European Affairs Minister for Immigration & Asylum Grand Duchy of Luxembourg Ankie Broekers-Knol Minister for Migration Netherlands Karin Keller-Sutter Head of the Federal Department of Justice and Policy Swiss Confederation Dear Vice President, dear Commissioner, Following the letter, dated June 1st, sent by my esteemed colleagues in copy regarding the movement of refugees – lawful residents within the European Τ: +30 2132128410M:[email protected]:Thivon 196-198, A.I. Rentis, Greece 18233 Union, allow me to offer some comments on the important topics that are raised and touch upon the core of the CEAS policy. The timing of the letter coincides with a period of increased migratory pressure for the MED5 countries. It also comes at a time when the Council and the European Parliament are discussing the new Pact on Migration and Asylum, aiming at finding sustainable and effective European solutions to a collective European problem, in line with our joint commitments. I need to underline from the outset that, clearly, the situation described in the letter is not one of secondary flows of asylum seekers, as provided in the framework of the Dublin III Regulation. It is about the mobility of persons that have been granted a legal refugee status by an EU Member State on the basis of its obligations under the 1951 Geneva Convention and the EU acquis. -

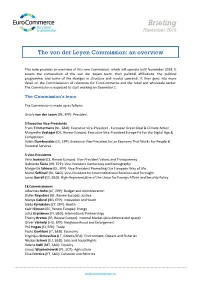

The Von Der Leyen Commission: an Overview

Briefing November 2019 The von der Leyen Commission: an overview This note provides an overview of this new Commission, which will operate until November 2024. It covers the composition of the von der Leyen team, their political affiliations, the political programme, and some of the changes in structure and modus operandi. It then goes into more detail on the Commissioners of relevance for EuroCommerce and the retail and wholesale sector. The Commission is expected to start working on December 1. The Commission’s team The Commission is made up as follows: Ursula von der Leyen (DE, EPP): President 3 Executive Vice-Presidents Frans Timmermans (NL, S&D): Executive Vice-President - European Green Deal & Climate Action Margrethe Vestager (DK, Renew Europe): Executive Vice-President Europe Fit For the Digital Age & Competition Valdis Dombrovskis (LV, EPP): Executive Vice-President for an Economy That Works For People & Financial Services 5 Vice-Presidents Věra Jourová (CZ, Renew Europe): Vice-President Values and Transparency Dubravka Šuica (HR, EPP): Vice-President Democracy and Demography Margaritis Schinas (EL, EPP): Vice-President Promoting Our European Way of Life Maroš Šefčovič (SK, S&D): Vice-President for Interinstitutional Relations and Foresight Josep Borrell (ES, S&D): High-Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy 18 Commissioners Johannes Hahn (AT, EPP): Budget and Administration Didier Reynders (BE, Renew Europe): Justice Mariya Gabriel (BG, EPP): Innovation and Youth Stella Kyriakides (CY, EPP): Health -

PANEL: the POWER of BELIEF Margaritis Schinas , Vice President, European Commission Archbishop Nikitas, Greek Orthodox Archbisho

PANEL: THE POWER OF BELIEF Margaritis Schinas, Vice President, European Commission Archbishop Nikitas, Greek Orthodox Archbishop, Great Britain Fatima Zaman, Advocate, Kofi Annan Foundation Moderated by Farah Nayeri, Culture Writer, The New York Times Each of the distinguished panelists brought with them a unique perspective based on their lived experiences of religious belief, political affiliation and identity within their respective communities. Each of them came with their own way of evaluating and combating intolerance based on belief. Archbishop Nikitas emphasized the importance of religious leaders and their role; removing their personal desires when deciphering divine messages and posited that religious leaders who succeed in this practice are able to manage religious disagreements or conflicts more peacefully and harmoniously than political leaders. According to Archbishop Nikitas, it is the obligation of religious leaders to guide others in “laying down their weapons” and “building bridges in place of walls.” Margaritis Schinas, a Vice President of the European Commission, spoke of the EU’s efforts to oppose acts of hatred and xenophobia through constitutional arrangements and community laws, saying that the antidote to the phenomena of anti-Semitism and xenophobia is “good policies,” which the EU is working on enthusiastically. Schinas regarded the EU as the “epicenter” and world champion of fundamental human rights fighting religious and minority intolerance, and described Europe not as a “bulldozer that imposes its own beliefs on others, but rather as a unique mirror that reflects our diversity, lifestyle, arts, religions, culture, language and history.” Fatima Zaman of the Kofi Annan Foundation described herself as a “hybrid” of multiple identities; a South Asian, a Briton, and a modern Muslim, each of which she says have been at odds with one another at some point in her life. -

BILTEN – Pregled Člankov Iz Časopisja [18

BILTEN – pregled člankov iz časopisja [18. jan. - 24. jan. 2019] [194] Novice – slovenski tednik na Koroškem, Celovec • Zmagovalke prihajajo iz treh šol. Novice – slovenski tednik na Koroškem, Celovec, št. 2, 18.1.2019, str. 2 Govorniški natečaj NSKS in KKZ http://www.novice.at/uncategorized/zmagovalke-prihajajo-iz-treh-sol/ Š Slika: Šest nastopajočih: nagrade pa so osvojile dijakinje iz treh šol (2., 3. in 4. z leve). Foto: Novice Slika: Žirija govorniškega natečaja v prostorih Dvojezične trgovske akademije v Celovcu. Foto: Novice Celovec. Na tradicionalnem govorniškem natečaju NSKS in KKZ ob podelitvi Tischlerjeve nagrade je žirija izmed šestih nastopajočih izbrala zmagovalke in na prvo mesto uvrstila Jano Haab, dijakinjo 6.a razreda Slovenske gimnazije s temo »Ali se lahko zapremo v svoj mali udobni svet ali je v resnici celotni svet postal podoben odprti vasi? Kaj so aktualna vprašanja današnje migracije in kaj ali kdo jo pospešuje?« Z isto temo je osvojila drugo mesto Hana Jusufagić (4.a DTAK), tretja pa je postala Zala Filipič (I. letnik Višje šole Šentpeter) s temo »Kolikor jezikov znaš – toliko veljaš! Je v današnjem globaliziranem svetu znanje ‚malih‘ jezikov še potrebno? Kaj pomeni zate osebno slovenski jezik na Koroškem?« Sodelovali so še in prejeli priznanje Lucija Pfeifer (6.a ZG/ZRG za Slovence v Celovcu), Tadej Ogorevc (4.a DTAK) in Kristina Mlakar (V. letnik Višje šole za gospodarske poklice v Šentpetru pri Šentjakobu). • Novice jutri. Avtor: Emanuel Polanšek. Novice – slovenski tednik na Koroškem, Celovec, št. 2, 18.1.2019, str. 2 http://www.novice.at/forum/komentar/novice-jutri/ Od izobraženega, kulturnega in olikanega človeka pričakujemo, da je v enaki meri samokritičen kakor je kritičen, da sta njegova socialna inteligenca in njegov čut solidarnosti razvita vsaj v isti meri kakor njegovo upravičeno stremljenje po napredovanju, zmagovanju in samouresničevanju, da mu v današnjem svetu, kjer visoko cenimo uspeh, bogastvo in moč, niso tuji sočutje, usmiljenje in hvaležnost. -

A First Appraisal of the Juncker Commission Hussein Kassim School

what’s new? a first appraisal of the juncker commission hussein kassim School of Politics, Philosophy, Language and Communication Studies The University of East Anglia, Norwich Research Park Norwich, NR4 7TJ United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Although still in its early phases, the Juncker Commission has already broken new ground. Not only is Jean-Claude Juncker the first Commission President to be selected by the Spitzenkandidaten process, an extra-constitutional system that has reconfigured the European Union’s institutional balance, but he has transformed the structure and operation of the College in order to create a more political, and therefore more effective, Commission, and made good – so far – on his promise ‘to do better on the bigger things and be small on the small things’. This article examines this three-fold transformation. It looks at the innovations and change associated with the Juncker Commission. It considers what motivated them and how they were achieved, sets them in historical perspective, and discusses their implications for the institutions and for the EU more broadly. Keywords Juncker Commission; European Commission; European Commission Presidency; Spitzenkanditaten 1 Although still at an early stage of its five-year term, the Juncker Commission is already one of the most noteworthy in the history of the European Union (EU). Its President, Jean-Claude Juncker, is the first to be nominated to the office as a result of the Spitzenkandidaten process, a system intended to mobilise interest in elections to the European Parliament and to enhance the EU’s legitimacy by linking the election results to the appointment of the European Commission.