Download (15MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration Rules

Last updated 14.06.2021 Jersey Immigration Rules CONTENTS Paragraphs Introduction 1-3 Implementation and Transitional Provisions 4 Provision for Irish citizens 5-5B Interpretation 6 PART 1: General provisions regarding leave to enter or remain in Jersey Leave to enter Jersey 7-9 Exercise of the power to refuse leave to enter Jersey or to cancel leave 10 to enter or remain which is in force Suspension of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 10A Cancellation of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 10B Requirement for persons arriving in Jersey to produce evidence of 11 identity and nationality Requirement for a person not requiring leave to enter Jersey to prove that he has the right of abode 12-14 Common Travel Area 15 Admission of certain British passport holders 16-17 Persons outside Jersey 17A – 17B Returning residents 18-20 Non-lapsing leave 20A Holders of restricted travel documents and passports 21-23 Leave to enter granted on arrival in Jersey 23A-23B Entry clearance 24-30C Variation of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 31-33A Withdrawn applications for variation of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 34J Undertakings 35 Medical 36-39 Official 1 Last updated 14.06.2021 PART 2: [not used] PART 3: Persons seeking to enter or remain in Jersey for studies Students 57-62 Re-sits of examinations 69-69E Writing up of thesis 69F-69K Spouses, civil partners or unmarried partners of students 76-78 Children of students 79-81 PART 4: Persons seeking to enter or remain in Jersey as a Minister of Religion or seeking to enter Jersey under the Youth -

Immigration Law Affecting Commonwealth Citizens Who Entered the United Kingdom Before 1973

© 2018 Bruce Mennell (04/05/18) Immigration Law Affecting Commonwealth Citizens who entered the United Kingdom before 1973 Summary This article outlines the immigration law and practices of the United Kingdom applying to Commonwealth citizens who came to the UK before 1973, primarily those who had no ancestral links with the British Isles. It attempts to identify which Commonwealth citizens automatically acquired indefinite leave to enter or remain under the Immigration Act 1971, and what evidence may be available today. This article was inspired by the problems faced by many Commonwealth citizens who arrived in the UK in the 1950s and 1960s, who have not acquired British citizenship and who are now experiencing difficulty demonstrating that they have a right to remain in the United Kingdom under the current law of the “Hostile Environment”. In the ongoing media coverage, they are often described as the “Windrush Generation”, loosely suggesting those who came from the West Indies in about 1949. However, their position is fairly similar to that of other immigrants of the same era from other British territories and newly independent Commonwealth countries, which this article also tries to cover. Various conclusions arise. Home Office record keeping was always limited. The pre 1973 law and practice is more complex than generally realised. The status of pre-1973 migrants in the current law is sometimes ambiguous or unprovable. The transitional provisions of the Immigration Act 1971 did not intersect cleanly with the earlier law leaving uncertainty and gaps. An attempt had been made to identify categories of Commonwealth citizens who entered the UK before 1973 and acquired an automatic right to reside in the UK on 1 January 1973. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

(Post)Colonial Women and the British Immigration System

EXAMINERS’ COPIES A Logic of Subordination: (Post)colonial Women and the British Immigration System DISSERTATION Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Coursework in Migration Studies at the University of Oxford 2019–2020 by 1042115 Word Count: 15,042 Oxford Department of International Development and School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography University of Oxford A Logic of Subordination: (Post)colonial Women and the British Immigration System Image credit: see references cited. Clockwise from top left corner: newspaper article on a Kenyan Asian woman seeking to migrate to Britain in 1970; an immigration raid van in Southall, London, the Empire Windrush in 1948; Kenyan Asians disembarking a plane in London in 1968; a poster in solidarity with the Stansted 15, who blocked a deportation flight in London in 2017; a protest in response to the 2018 Windrush scandal; a protest by London’s Southall Black Sisters; a 1979 newspaper article on the practice of virginity testing at Heathrow airport. 2 Abstract The empirical realities of many migrant women in Britain often indicate vulnerability to various harms. These lived experiences reflect the institutionalised insecurity produced by the confluence of immigration law and varied social processes, and can therefore be understood as illustrative of migrants’ ‘precarity’ in Britain. Many migrants in Britain are also (post)colonial peoples, who carry histories of colonial subjugation. Recent migration scholarship has therefore illustrated a turn towards explaining immigration controls as a tool for maintaining Britain’s colonial ethic. According to this narrative, immigration law prevents (post)colonial peoples’ access to the advantage concentrated in Britain, produced through the same processes that have enabled their subjugation. -

Download (2260Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/4527 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. God and Mrs Thatcher: Religion and Politics in 1980s Britain Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2010 Liza Filby University of Warwick University ID Number: 0558769 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. ……………………………………………… Date………… 2 Abstract The core theme of this thesis explores the evolving position of religion in the British public realm in the 1980s. Recent scholarship on modern religious history has sought to relocate Britain‟s „secularization moment‟ from the industrialization of the nineteenth century to the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s. My thesis seeks to add to this debate by examining the way in which the established Church and Christian doctrine continued to play a central role in the politics of the 1980s. More specifically it analyses the conflict between the Conservative party and the once labelled „Tory party at Prayer‟, the Church of England. Both Church and state during this period were at loggerheads, projecting contrasting visions of the Christian underpinnings of the nation‟s political values. The first part of this thesis addresses the established Church. -

Who Needs Leave to Remain? the Uncertain Legal Consequences of Missing the EU Settlement Scheme Deadline

Who needs leave to remain? The uncertain legal consequences of missing the EU settlement scheme deadline Bernard Ryan, Professor of Law, University of Leicester 22 June 2021 Introduction This note addresses the implications of an individual’s missing the 30 June 2021 deadline for applications to register under the EU settlement scheme. Article 18(3) of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement appears to protect individuals’ rights from the time that they make a late application.1 The focus here is on the status in United Kingdom law of persons eligible to apply under the settlement scheme, who fail to apply on time, and who stay in the United Kingdom. It makes no distinction between three scenarios where a person may be unregistered: (i) prior to a late application and successful registration; (ii) where a late application is made which is unsuccessful; and (iii) where no application is made. The analysis here of the status of those who are unregistered takes a historical starting-point. It shows that, from 1982, those exercising free movement rights in the United Kingdom were exempt from a requirement to obtain leave to enter.2 That led to an interpretation - set out in particular by Lord Hoffman in the House of Lords in Wolke in 1997 – that those who ceased to be eligible for free movement rights were lawfully present in the United Kingdom if they stayed on. Subsequently, a different view emerged, that persons who cease to be exempt under the Immigration Act 1971 – including EEA+ nationals who qualified for free movement rights - “require leave”.3 This different interpretation is of broad significance, as many legislative provisions came to use versions of that formulation. -

EU Londoners Hub

EU Londoners Hub The Mayor, Sadiq Khan, has been clear that EU citizens living in London belong and are welcome in our great city. To make sure EU citizens and their families have all the information they need about living in London after Brexit we have created this hub. We have launched a few resource sections to give you clear and impartial information and, if required, guide you to further support and advice. This page will continue to be updated. Sign me up for EU Londoner updates Brexit: what this means for EU Londoners The UK voted to leave the European Union in June 2016. Below we have provided answers to some of the questions you may have about this decision and how Brexit impacts you. What is Brexit? Brexit is the popular term for the process of the UK leaving the EU, as a result of the referendum held on 23 June 2016. In March 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May gave official notice to the EU of the UK’s intention to leave the EU - referred to as the Article 50 notice. This was the start of a two- year negotiation process to agree the terms under which the UK would leave, and what its future relationship with the EU would be. The UK has been a member of the EU since 1973. This means that many structures, arrangements and agreements in place as part of the UK’s membership of the EU become redundant when the UK leaves the EU. New structures, arrangement and agreements need to replace these, which will come under UK law, not EU law. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation

ENGLAND’S ANSWER: IDENTITY AND LEGITIMATION IN BRITISH FOREIGN POLICY By STUART STROME A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 1 © 2014 Stuart Strome 2 To my grandfather 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my mom, dad, grandparents, and entire family for supporting me through this taxing process. Thank you for being voices of encouragement through can sometimes be a discouraging undertaking. Thank you to the rest of my family for being there when I needed you most. I truly love you all! I would like to thank my professors and colleagues, who provided guidance, direction and invaluable advice during the writing process. They say you don’t get to choose your family yourself, although whoever up there chose it did a wonderful job. I’d like to thank all my colleagues and mentors who provided intellectual inspiration and encouragement. Most specifically, I’d like to thank my dissertation committee, Dan O’Neill, Ido Oren, Aida Hozic, Matthew Jacobs, and above all, my committee chair, Leann Brown. Dr. Brown was incredibly supportive throughout the process, kept me grounded and on track, and provided a shoulder to cry on when needed (which was often!) I’ve never heard of a committee chair that would regularly answer phone calls to field questions, or sometimes just to act as a sounding post with whom to flesh out ideas. You are an inspiration, and I am lucky to have you as a mentor and friend. -

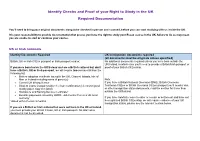

Identify Checks and Proof of Your Right to Study in the UK Required

Identify Checks and Proof of your Right to Study in the UK Required Documentation You’ll need to bring your original documents along to be checked in person and scanned, before you can start studying with us inside the UK. It is your responsibility to provide documentation that proves you have the right to study your Essex course in the UK, failure to do so may mean you are unable to start or continue your course. UK or Irish nationals Identity Documents Required UK Immigration documents required (all documents must be originals unless specified) British, UK or Irish Citizen passport or Irish passport card or; No additional documents required unless you were born outside the UK/Ireland, in which case you’ll need to provide a British/Irish passport or If you were born inside the UK/Ireland and are a British national but don’t proof of your British Citizenship. have a British, UK or Irish passport, we will require two documents from the following list: Birth or adoption certificate issued in the UK, Channel Islands, Isle of Man or Ireland including name of parent(s) Note: Current UK driving licence If you have a British National Overseas (BNO); British Overseas Student Loans Company tuition fee loan confirmation (electronic/good Territories Citizen or British Overseas Citizen passport you’ll need a visa quality paper copy accepted) or other immigration status documents, read the section for those from Disclosure and Barring Service Certificate* outside the UK/Ireland. Benefits paperwork issued by HMRC, Job Centre Plus or a UK local authority* If you have Indefinite leave to enter or remain or settlement and have not *dated within the last 3 months been granted British Citizenship, we will require evidence of your UK immigration status, please see the relevant section below. -

The Transcription Centre

The Transcription Centre: An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: The Transcription Centre, circa 1962-1977 Title: The Transcription Centre Records Dates: 1931-1986 (bulk 1960-1977) Extent: 25 boxes (10.50 linear feet) Abstract: The records of the Transcription Centre comprise scripts and manuscripts, correspondence, legal documents, business records, ephemera, photographs, and clippings spanning the years 1931 to 1986. Languages: English, Hausa, Swahili, German, French, and Italian . Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchase, 1990 (R12142) Processed by: Bob Taylor, 2008 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center The Transcription Centre, circa 1962-1977 Organizational History The Transcription Centre began its brief but significant life in February 1962 under the direction of Dennis Duerden (1927-2006), producing and distributing radio programs for and about Africa. Duerden was a graduate of Queen’s College, Oxford and had served as principal of the Government Teachers’ College at Keffi, Nigeria and later as producer of the Hausa Service of the BBC. As an artist and educator with experience in West Africa, as well as a perceptive critic of African art he was a natural in his new post. The Transcription Centre was created with funding provided initially by the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF) to foster non-totalitarian cultural values in sub-Saharan Africa in implicit opposition to Soviet-encouraged committed political attitudes among African writers and artists. Much of the CCF’s funding and goals were subsequently revealed to have come from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. The stress between the CCF’s presumed wish to receive value for their investment in the Transcription Centre and Duerden’s likely belief that politically-based programming would alienate the very audience it sought permeated his activities throughout his years with the radio service. -

Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill

Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill [AS AMENDED ON REPORT] CONTENTS Appeals 1 Variation of leave to enter or remain 2Removal 3 Grounds of appeal 4 Entry clearance 5 Failure to provide documents 6 Refusal of leave to enter 7 Deportation 8 Legal aid 9 Abandonment of appeal 10 Grants 11 Continuation of leave 12 Asylum and human rights claims: definition 13 Appeal from within United Kingdom: certification of unfounded claim 14 Consequential amendments Employment 15 Penalty 16 Objection 17 Appeal 18 Enforcement 19 Code of practice 20 Orders 21 Offence 22 Offence: bodies corporate, &c. 23 Discrimination: code of practice 24 Temporary admission, &c. 25 Interpretation 26 Repeal Information 27 Documents produced or found 28 Fingerprinting 29 Attendance for fingerprinting 30 Proof of right of abode 31 Provision of information to immigration officers HL Bill 74 54/1 ii Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill 32 Passenger and crew information: police powers 33 Freight information: police powers 34 Offence 35 Power of Revenue and Customs to obtain information 36 Duty to share information 37 Information sharing: code of practice 38 Disclosure of information for security purposes 39 Disclosure to law enforcement agencies 40 Searches: contracting out 41 Section 40: supplemental 42 Information: embarking passengers Claimants and applicants 43 Accommodation 44 Failed asylum-seekers: withdrawal of support 45 Integration loans 46 Inspection of detention facilities 47 Removal: persons with statutorily extended leave 48 Removal: cancellation of leave 49 Capacity to make nationality application 50 Procedure 51 Fees 52 Fees: supplemental Miscellaneous 53 Arrest pending deportation 54 Refugee Convention: construction 55 Refugee Convention: certification 56 Deprivation of citizenship 57 Deprivation of right of abode 58 Acquisition of British nationality, &c.