(Post)Colonial Women and the British Immigration System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Immigration Rules

Last updated 14.06.2021 Jersey Immigration Rules CONTENTS Paragraphs Introduction 1-3 Implementation and Transitional Provisions 4 Provision for Irish citizens 5-5B Interpretation 6 PART 1: General provisions regarding leave to enter or remain in Jersey Leave to enter Jersey 7-9 Exercise of the power to refuse leave to enter Jersey or to cancel leave 10 to enter or remain which is in force Suspension of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 10A Cancellation of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 10B Requirement for persons arriving in Jersey to produce evidence of 11 identity and nationality Requirement for a person not requiring leave to enter Jersey to prove that he has the right of abode 12-14 Common Travel Area 15 Admission of certain British passport holders 16-17 Persons outside Jersey 17A – 17B Returning residents 18-20 Non-lapsing leave 20A Holders of restricted travel documents and passports 21-23 Leave to enter granted on arrival in Jersey 23A-23B Entry clearance 24-30C Variation of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 31-33A Withdrawn applications for variation of leave to enter or remain in Jersey 34J Undertakings 35 Medical 36-39 Official 1 Last updated 14.06.2021 PART 2: [not used] PART 3: Persons seeking to enter or remain in Jersey for studies Students 57-62 Re-sits of examinations 69-69E Writing up of thesis 69F-69K Spouses, civil partners or unmarried partners of students 76-78 Children of students 79-81 PART 4: Persons seeking to enter or remain in Jersey as a Minister of Religion or seeking to enter Jersey under the Youth -

Immigration Law Affecting Commonwealth Citizens Who Entered the United Kingdom Before 1973

© 2018 Bruce Mennell (04/05/18) Immigration Law Affecting Commonwealth Citizens who entered the United Kingdom before 1973 Summary This article outlines the immigration law and practices of the United Kingdom applying to Commonwealth citizens who came to the UK before 1973, primarily those who had no ancestral links with the British Isles. It attempts to identify which Commonwealth citizens automatically acquired indefinite leave to enter or remain under the Immigration Act 1971, and what evidence may be available today. This article was inspired by the problems faced by many Commonwealth citizens who arrived in the UK in the 1950s and 1960s, who have not acquired British citizenship and who are now experiencing difficulty demonstrating that they have a right to remain in the United Kingdom under the current law of the “Hostile Environment”. In the ongoing media coverage, they are often described as the “Windrush Generation”, loosely suggesting those who came from the West Indies in about 1949. However, their position is fairly similar to that of other immigrants of the same era from other British territories and newly independent Commonwealth countries, which this article also tries to cover. Various conclusions arise. Home Office record keeping was always limited. The pre 1973 law and practice is more complex than generally realised. The status of pre-1973 migrants in the current law is sometimes ambiguous or unprovable. The transitional provisions of the Immigration Act 1971 did not intersect cleanly with the earlier law leaving uncertainty and gaps. An attempt had been made to identify categories of Commonwealth citizens who entered the UK before 1973 and acquired an automatic right to reside in the UK on 1 January 1973. -

Who Needs Leave to Remain? the Uncertain Legal Consequences of Missing the EU Settlement Scheme Deadline

Who needs leave to remain? The uncertain legal consequences of missing the EU settlement scheme deadline Bernard Ryan, Professor of Law, University of Leicester 22 June 2021 Introduction This note addresses the implications of an individual’s missing the 30 June 2021 deadline for applications to register under the EU settlement scheme. Article 18(3) of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement appears to protect individuals’ rights from the time that they make a late application.1 The focus here is on the status in United Kingdom law of persons eligible to apply under the settlement scheme, who fail to apply on time, and who stay in the United Kingdom. It makes no distinction between three scenarios where a person may be unregistered: (i) prior to a late application and successful registration; (ii) where a late application is made which is unsuccessful; and (iii) where no application is made. The analysis here of the status of those who are unregistered takes a historical starting-point. It shows that, from 1982, those exercising free movement rights in the United Kingdom were exempt from a requirement to obtain leave to enter.2 That led to an interpretation - set out in particular by Lord Hoffman in the House of Lords in Wolke in 1997 – that those who ceased to be eligible for free movement rights were lawfully present in the United Kingdom if they stayed on. Subsequently, a different view emerged, that persons who cease to be exempt under the Immigration Act 1971 – including EEA+ nationals who qualified for free movement rights - “require leave”.3 This different interpretation is of broad significance, as many legislative provisions came to use versions of that formulation. -

EU Londoners Hub

EU Londoners Hub The Mayor, Sadiq Khan, has been clear that EU citizens living in London belong and are welcome in our great city. To make sure EU citizens and their families have all the information they need about living in London after Brexit we have created this hub. We have launched a few resource sections to give you clear and impartial information and, if required, guide you to further support and advice. This page will continue to be updated. Sign me up for EU Londoner updates Brexit: what this means for EU Londoners The UK voted to leave the European Union in June 2016. Below we have provided answers to some of the questions you may have about this decision and how Brexit impacts you. What is Brexit? Brexit is the popular term for the process of the UK leaving the EU, as a result of the referendum held on 23 June 2016. In March 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May gave official notice to the EU of the UK’s intention to leave the EU - referred to as the Article 50 notice. This was the start of a two- year negotiation process to agree the terms under which the UK would leave, and what its future relationship with the EU would be. The UK has been a member of the EU since 1973. This means that many structures, arrangements and agreements in place as part of the UK’s membership of the EU become redundant when the UK leaves the EU. New structures, arrangement and agreements need to replace these, which will come under UK law, not EU law. -

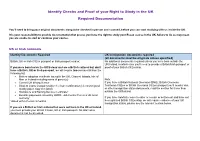

Identify Checks and Proof of Your Right to Study in the UK Required

Identify Checks and Proof of your Right to Study in the UK Required Documentation You’ll need to bring your original documents along to be checked in person and scanned, before you can start studying with us inside the UK. It is your responsibility to provide documentation that proves you have the right to study your Essex course in the UK, failure to do so may mean you are unable to start or continue your course. UK or Irish nationals Identity Documents Required UK Immigration documents required (all documents must be originals unless specified) British, UK or Irish Citizen passport or Irish passport card or; No additional documents required unless you were born outside the UK/Ireland, in which case you’ll need to provide a British/Irish passport or If you were born inside the UK/Ireland and are a British national but don’t proof of your British Citizenship. have a British, UK or Irish passport, we will require two documents from the following list: Birth or adoption certificate issued in the UK, Channel Islands, Isle of Man or Ireland including name of parent(s) Note: Current UK driving licence If you have a British National Overseas (BNO); British Overseas Student Loans Company tuition fee loan confirmation (electronic/good Territories Citizen or British Overseas Citizen passport you’ll need a visa quality paper copy accepted) or other immigration status documents, read the section for those from Disclosure and Barring Service Certificate* outside the UK/Ireland. Benefits paperwork issued by HMRC, Job Centre Plus or a UK local authority* If you have Indefinite leave to enter or remain or settlement and have not *dated within the last 3 months been granted British Citizenship, we will require evidence of your UK immigration status, please see the relevant section below. -

Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill

Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill [AS AMENDED ON REPORT] CONTENTS Appeals 1 Variation of leave to enter or remain 2Removal 3 Grounds of appeal 4 Entry clearance 5 Failure to provide documents 6 Refusal of leave to enter 7 Deportation 8 Legal aid 9 Abandonment of appeal 10 Grants 11 Continuation of leave 12 Asylum and human rights claims: definition 13 Appeal from within United Kingdom: certification of unfounded claim 14 Consequential amendments Employment 15 Penalty 16 Objection 17 Appeal 18 Enforcement 19 Code of practice 20 Orders 21 Offence 22 Offence: bodies corporate, &c. 23 Discrimination: code of practice 24 Temporary admission, &c. 25 Interpretation 26 Repeal Information 27 Documents produced or found 28 Fingerprinting 29 Attendance for fingerprinting 30 Proof of right of abode 31 Provision of information to immigration officers HL Bill 74 54/1 ii Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Bill 32 Passenger and crew information: police powers 33 Freight information: police powers 34 Offence 35 Power of Revenue and Customs to obtain information 36 Duty to share information 37 Information sharing: code of practice 38 Disclosure of information for security purposes 39 Disclosure to law enforcement agencies 40 Searches: contracting out 41 Section 40: supplemental 42 Information: embarking passengers Claimants and applicants 43 Accommodation 44 Failed asylum-seekers: withdrawal of support 45 Integration loans 46 Inspection of detention facilities 47 Removal: persons with statutorily extended leave 48 Removal: cancellation of leave 49 Capacity to make nationality application 50 Procedure 51 Fees 52 Fees: supplemental Miscellaneous 53 Arrest pending deportation 54 Refugee Convention: construction 55 Refugee Convention: certification 56 Deprivation of citizenship 57 Deprivation of right of abode 58 Acquisition of British nationality, &c. -

Immigration Act 2014

Immigration Act 2014 CHAPTER 22 Explanatory Notes have been produced to assist in the understanding of this Act and are available separately £20.75 Immigration Act 2014 CHAPTER 22 CONTENTS PART 1 REMOVAL AND OTHER POWERS Removal 1 Removal of persons unlawfully in the United Kingdom 2 Restriction on removal of children and their parents etc 3 Independent Family Returns Panel Powers of immigration officers 4Enforcement powers Detention and bail 5 Restrictions on detention of unaccompanied children 6 Pre-departure accommodation for families 7 Immigration bail: repeat applications and effect of removal directions Biometrics 8 Provision of biometric information with immigration applications 9 Identifying persons liable to detention 10 Provision of biometric information with citizenship applications 11 Biometric immigration documents 12 Meaning of “biometric information” 13 Safeguards for children 14 Use and retention of biometric information ii Immigration Act 2014 (c. 22) PART 2 APPEALS ETC 15 Right of appeal to First-tier Tribunal 16 Report by Chief Inspector on administrative review 17 Place from which appeal may be brought or continued 18 Review of certain deportation decisions by Special Immigration Appeals Commission 19 Article 8 of the ECHR: public interest considerations PART 3 ACCESS TO SERVICES ETC CHAPTER 1 RESIDENTIAL TENANCIES Key interpretation 20 Residential tenancy agreement 21 Persons disqualified by immigration status or with limited right to rent Penalty notices 22 Persons disqualified by immigration status not to be leased premises 23 Penalty notices: landlords 24 Excuses available to landlords 25 Penalty notices: agents 26 Excuses available to agents 27 Eligibility period 28 Penalty notices: general Objections, appeals and enforcement 29 Objection 30 Appeals 31 Enforcement Codes of practice 32 General matters 33 Discrimination General 34 Orders 35 Transitional provision 36 Crown application 37 Interpretation Immigration Act 2014 (c. -

The Common Travel Area: More Than Just Travel

The Common Travel Area: More Than Just Travel A Royal Irish Academy – British Academy Brexit Briefing Professor Imelda Maher MRIA October 2017 The Common Travel Area: More Than Just Travel About this Series The Royal Irish Academy-British Academy Brexit Briefings is a series aimed at highlighting and considering key issues related to the UK’s withdrawal from the EU within the context of UK-Ireland relations. This series is intended to raise awareness of the topics and questions that need consideration and/ or responses as the UK negotiates its exit from EU. The Royal Irish Academy/Acadamh Ríoga na hÉireann (RIA) Ireland’s leading body of experts in the sciences, humanities and social sciences. Operating as an independent, all-island body, the RIA champions excellence in research, and teaching and learning, north and south. The RIA supports scholarship and promotes an awareness of how science and the humanities enrich our lives and benefit society. Membership of the RIA is by election and considered the highest academic honour in Ireland. The British Academy The UK’s independent national academy representing the humanities and social sciences. For over a century it has supported and celebrated the best in UK and international research and helped connect the expertise of those working in these disciplines with the wider public. The Academy supports innovative research and outstanding people, influences policy and seeks to raise the level of public understanding of some of the biggest issues of our time, through policy reports, publications and public events. The Academy represents the UK’s research excellence worldwide in a fast-changing global environment. -

Common Travel Area

Common Travel Area Version 9.0 Page 1 of 92 Published for Home Office staff on 01 July 2021 Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................... 2 About this guidance .................................................................................................... 6 Contacts ................................................................................................................. 6 Publication .............................................................................................................. 6 Changes from last version of this guidance ............................................................ 6 Common Travel Area – background........................................................................... 7 Legislation .................................................................................................................. 9 The Immigration Act 1971 ....................................................................................... 9 Schedule 4 – Interaction between the immigration laws of the UK and the Crown Dependencies ..................................................................................................... 9 Immigration (Control of Entry through Republic of Ireland) Order 1972 .................. 9 The status of Irish Citizens under UK legislation ............................................... 10 Legislation underpinning the immigration systems of the Crown Dependencies .. 11 The British Nationality Act 1981 -

Immigration and Right of Abode: Withdrawn

This guidance was withdrawn on 16 June 2021 Passport policy - Immigration and Right of Abode Right of Abode in the United Kingdom BCs with connection to the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man Passports with Gibraltar ´Belongers´ and ´non-belongers´ Applicants without ROA but entitled to re-admission to the UK Applicants subject to restrictions under the Immigration Act 1971 Applicants with the right of abode in Hong Kong Establishing settlement claims of parents Irish citizens Settled Status for Vietnamese refugees and Gurkhas Other refugees and asylum seekers Other members of HM Forces subject to Service Law No time limit stamps Permanent Residence label Right of Abode certificates European Union Format Visa (UFV) “Red” UK visa Annex A - Training noteArchived for Settlement Right of Abode in the United Kingdom A person with the nationality status of British citizen automatically has the Right Of Abode (ROA) in the United Kingdom under the provisions of section 2 of the Immigration Act 1971, as amended by section 39 of the British Nationality Act 1981, a copy of which can be found in Order Book Volume 2. The observation 'THE HOLDER HAS THE RIGHT OF ABODE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM' is only entered in passports of British Subjects who have a right of abode in the United Kingdom under the provisions of the 1971 Act. This guidance was withdrawn on 16 June 2021 Applicants may produce evidence of immigration status in the following ways:- ROA under section 2(1)(c) Immigration Act: • A status letter from the United Kingdom Border Agency (UKBA) confirming the applicant’s 2(1)(c) ROA status. -

Control of Immigration

Home Office Statistical Bulletin The Research, Development CONTROL OF IMMIGRATION : and Statistics Directorate exists to improve policy making, decision taking and practice in support of the Home Office STATISTICS purpose and aims, to provide the public and Parliament with information necessary for informed debate and to UNITED KINGDOM publish information for future use. 2009 Statistical Bulletins are prepared by staff in Home Office Statistics under the National Statistics Code of Practice and can be downloaded from both the UK Statistics Authority website and the Home Office Research, Development and Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds © Crown Copyright 2010 ISSN 1358-510X August 2010 15/10 CONTROL OF IMMIGRATION: STATISTICS UNITED KINGDOM 2009 ISSN 1358-510X ISBN 978-1-84987-250-8 August 2010 3 INTRODUCTION This bulletin presents the 2009 data on the control of immigration. It is the latest annual series available and aims to give an overview of the work of the UK Border Agency and other immigration processes. Further information is provided via supplementary web tables, which are available at: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/immigration-asylum-stats.html. Prior to 2008, data on the control of immigration were published in two separate bulletins: Control of Immigration: Statistics United Kingdom, published in the form of a Command Paper concentrating on border control, enforcement and compliance and managed migration; and Asylum Statistics United Kingdom. Figures for 2009 shown in this publication are provisional and subject to change. Forthcoming publications Quarterly provisional information on the key findings included in this bulletin are published in the Control of Immigration: Quarterly Statistical Summary, United Kingdom bulletin. -

Irish Citizens in Immigration Law After Brexit

Recognition after All: Irish Citizens in Immigration Law after Brexit [Post-peer review version, submitted on 1 October 2020] BERNARD RYAN* Abstract This article is concerned with the position of Irish citizens in British immigration law, both historically, and once the free movement of persons regime ceases. Drawing on legal and archival material, it traces the status of Irish citizens in British immigration law since the establishment of the Irish state in 1921- 1922. Until the early 1960s, Irish citizens were treated as British subjects, or as if they were, and therefore benefitted from right to enter and reside in the United Kingdom, and immunity from deportation from it. When the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Immigration Act 1971 introduced immigration restrictions and deportation for British subjects from the colonies and Commonwealth, the policy was to exempt Irish citizens in practice. Although the common travel area appears to have been the primary reason for that policy, it was highly controversial at the time, as it reinforced the view that that legislation was racially discriminatory. The legacy of that controversy, however, was inadequate provision for Irish citizens in immigration law after 1 January 1973, something which was masked by the availability of EU free movement rights as an alternative. These inadequacies are being addressed as the free movement of persons regime ceases, through an exemption from requirements to obtain leave to enter and remain in the Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill. It is linked to the wider normalisation of the two states’ relationship, which has enabled full recognition of the established patterns of migration and mobility between them.