I MIGHT BE WRONG and AS IF IT WAS MADE of GLASS by Stephen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banner Roundo) 2

Il =' II I-·I·III--· I- I II · I -- - I --- L- Ir I , · -'--r- · I - I · I 2 CAZIING HOME FOR MONEY TUST GOT CHEAPER. r ^M~~rli~ftlilll~~l^Jinl~~lia~~iI~syilli^^ii~~~nj~ia~gjiiiTT^^~ Now there's a cheaper way to call home-or anywhere else. coin and collect calls. You can even use your Home Federal Just buy a Pre-Paid Phone Card at BASED ON A 3 MINUTE CALL FROM NEW YORK TO: Pre-Paid Phone Card for cellular a\ our branch on campus or your Pay Phone AT&T Home Federal phone calls and pagers. At a\ Credit Card Phone Card r- nearest Home Federal branch. Anywhere in the U.S. $5.50 $3.41 $0.75 Home Federal, you don't have France, Germany, Norway, $12.60 $7.44 $1.50 E You'll enjoy savings of 40-70% Sweden, Switzerland and U.K. to go far to call far-for less. Just Italy $19.50 $9.65 $2.25 IQ) on pay phone and credit card Korea $19.50 $8.78 $4.00 think of what you can do with O Brazil $11.30 $11.24 $4.00 O long distance rates, and 150%o on all that spare change. $.- 0 516-689-8900 Student Activities Center, Lower Level Monday-Friday 9:00AM-4:30PM, Thursdays 9:00AM-7:00PM di o c> (&I0 4-^0 <^ YOu DON'T HAVE To CO FAR To GET FAR:m * < $4 I;'eniber r)IC 31 CONVENIENT BRANCH LOCATIONS THROUGHOUT BROOKLYN, QUEENS, NASSAU, SUFFOLKAND STATEN ISLAND EQUALHOUSING LENDER k-I I 3 at lIving Pla za Sold~~~~~~~~~~~~~~1Sold OuJrsOut Jars of ClaClay ConerConcert L at Irin zt7a BY DIANA GINGO through the set with energy and strong lead Statesmant Editor _ _ vocals. -

Wholemegillah

Congregation Beth Shalom Rodfe Zedek The WholeMegillah September & October 2017 10 Elul, 5777 – 11 Heshvan, 5778 Inside this issue Reflections and Schedule for the High Holy Days pg 6–7 Rabbi Bellows’ Teaching for Sukkot................................3 Editorial on the Sh’ma by Andy Schatz...................4–5 Ellen Nodelman Presents House of Peace and Justice, the History of CBSRZ at Books & Bagels.................10–11 News from the Kivvun Korner...................12–13 Baruch Zvi Ring, Memorial Tablet and Omer Calendar, Jewish Museum, New York City (Google Art Project) www.cbsrz.org T H A N K Y O U IN THIS ISSUE to the following donors from 6/6/2017 to 8/6/2017 2nd Century Campaign Carol, Sofia and Eva LeWitt: in memory of From Our Rabbi Rita Christopher & David Frank Dr. Abraham LeWitt & Nellie LeWitt Edward & Linda Pinn Carol LeWitt & Bruce Josephy: in memory of 3 Rabbi Marci Bellows Michael Roth & Kari Weil Phil Burzin, Bernie Slater, Bennett Millstein and 860-526-8920 Andy Schatz & Barbara Wolf Harvey Redak [email protected] Natalie Lindstrom: in memory of Lee Marcus Sh’ma Editorial Tzedakah Collective Norman Needleman: in memory of Ann Needleman Cantor Belinda Brennan Cantor Educator Sophie & Maurice Khaski Norman Needleman: in memory of Karen Joy 4–5 Berfond 860-526-8920 Harvey Payton: in memory of William Payton [email protected] Food/Beverage Fund Saul & Hila Rosen: in memory of Susan Cohen Ethan Goller & Rona Malakoff High Holiday Maxine Klein Glassberg, Harry Rosen, Mildred Rosen and President Debra Landrey Frances -

The Gift of Israel Jars of Clay Open up at UMBC Books, Java and Happy

I • Sept. 2000 ' ' J I PAGE 15 Jamie Peck trudges Curio Shoppe 20 through Survivor tell-all becomes She-Ra 23 Adam Craigmiles reach- Getting personal 20 es Sunny California with Persiflage 24 (insert name here] b y a n n a k a p I a n week has passed, and Andrew's second week of con a small green plastic test entries. Andrew, [INH] is Ahippo is still sitting very sorry that you did not get around the Retriever Weekly the prize. You really do office, wondering why no one deserve one for your consisten has come to pick it up yet. cy. Tune in next week for fur Where are you, Sal Paradise? ther prize announcements. Why won't you pick up your The official winner and the prize? If you can, please stop recipient of a book about cho by the office on Friday after lesterol whose title [INH] can noon. [Insert Name Here] is not recall at the moment is dying to meet a fellow someone named BigDon. His Kerouac fan. entry is as follows: Now on to the contest busi "Classes and their slogans ness. This is the second week Art: Where homicidal rages in a row that people have sub and clay can earn you a degree. mitted entries, which makes Greek Mythology: Large [INH] feel all warm and fuzzy naked men are the norm. inside. If this keeps happening, History: Undeniable proof it will just have to melt into a that people like to kill each big happy puddle on the floor. -

A Semiological Analysis of Contemporary Christian Music (Ccm) As Heard on 95.5 Wfhm-Fm Cleveland, Ohio "The Fish" Radio Station (July 2001 to July 2006)

A SEMIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC (CCM) AS HEARD ON 95.5 WFHM-FM CLEVELAND, OHIO "THE FISH" RADIO STATION (JULY 2001 TO JULY 2006) A dissertation submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alexandra A. Vago May 2011 Dissertation written by Alexandra A. Vago B.S., Temple University, 1994 M.M., Kent State University, 1998 M.A., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by ___________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Denise Seachrist ___________________________, Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Ralph Lorenz ___________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Thomas Janson ___________________________, David Odell-Scott Accepted by ___________________________, Director, School of Music Denise Seachrist ___________________________, Dean, College of the Arts John R. Crawford ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS...................................................................................................iii! LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... iv! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. v! CHAPTER ! I. 95.5 FM: FROM WCLV TO WFHM "THE FISH"! A Brief History ............................................................................................ 6! Why Radio?.............................................................................................. -

A Metaphoric and Generic Criticism of Jars of Clayâ•Žs Concept Video, Good Monsters

Good Monsters Criticism 1 Running head: GOOD MONSTERS CRITICISM Monsters, Of Whom I am Chief: A Metaphoric and Generic Criticism of Jars of Clay’s Concept Video, Good Monsters Jennifer R. Brown A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2008 Good Monsters Criticism 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Faith Mullen, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Monica Rose, D.Min. Committee Member ______________________________ Michael P. Graves, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date Good Monsters Criticism 3 Abstract Images of Frankenstein and the boogeyman no doubt come to mind when one thinks of monsters. Can a monster be “good”? What does it mean to be something typically personified as bad and yet apply such a contradictory adjective? What do men dancing in brightly colored costumes have to do with people dying every day in sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world? These are just some of the questions inspired by a curious and unforgettable artifact. This study is a rhetorical analysis of the Jars of Clay song and concept video, Good Monsters . Within the professional and social context of the video’s release are many clues as to the intention of the creators of the text. How can a greater meaning be understood? The first methodology used in this study is metaphoric criticism, which is applied to the lyrics, visual images, and musical movements of the artifact. -

Rebecca Rubert 12/9/98 English 30

Rebecca Rubert 12/9/98 English 30 “But we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us." II Corinthians 4:7 “Like a Child” Having compared their music to a banana split, the band Jars of Clay has sweetened both Christian and non-Christian audiences with their music. As one of the only Christian bands to dive into the secular world, Jars of Clay is unique. Though originally a Christian band, Jars of Clay was surprised at the success of their single, “Flood,” in the secular market (Hefner 1). Both Christians and non-Christians alike have often criticized them for crossing over into the secular realm. However, they are not looking for fame or for money. Unlike Christian artists who delve into secular music with albums geared to a more integrated audience, the band wants to have fun playing their music as well as reach out to an audience who would not normally listen to a Christian influence (Lutes 2). Charlie Lowell, Dan Haseltine, Matt Bronleewe and Stephen Mason met at Greenville College while studying Contemporary Christian Music. As an assignment for their recording class, they recorded a few songs together. They eventually played some of these songs for friends and in clubs in the area. On a whim, they decided to enter a contest sponsored by the Contemporary Christian Music magazine for the best new Christian band, and they won (“The History” 2). With this instant recognition, they signed with Essential Records, a recording company, and their single, “Flood,” was given to the Silvertone division of the company to be released to alternative radio. -

Outdoor Sunday Service 01/31/2021

Outdoor Sunday Service 01/31/2021 Call to Worship Isaiah 40:28-31 Have you not known? Have you not heard? The LORD is the everlasting God, the Creator of the ends of the earth. He does not faint or grow weary; his understanding is unsearchable. 29 He gives power to the faint, and to him who has no might he increases strength. 30 Even youths shall faint and be weary, and young men shall fall exhausted; 31 but they who wait for the LORD shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings like eagles; they shall run and not be weary; they shall walk and not faint. Desert Song Brooke Fraser This is my prayer in the desert when all that's within me feels dry This is my prayer in my hunger and need my God is the God who provides This is my prayer in the fire in weakness or trial or pain There is a faith proved of more worth than gold So refine me, Lord through the flame I will bring praise, I will bring praise, no weapon formed against me shall remain I will rejoice, I will declare God is my victory and He is here This is my prayer in the battle when triumph is still on its way I am a conqueror and co-heir with Christ so firm on His promise I'll stand I will bring praise, I will bring praise, no weapon formed against me shall remain I will rejoice, I will declare God is my victory and He is here All of my life in every season You are still God I have a reason to sing, I have a reason to worship All of my life in every season You are still God I have a reason to sing, I have a reason to worship All of my life in every season You are still God I have a reason to sing, I have a reason to worship All of my life in every season You are still God I have a reason to sing, I have a reason to worship I will bring praise, I will bring praise, no weapon formed against me shall remain I will rejoice, I will declare God is my victory and He is here This is my prayer in the harvest when favor and providence flow I know I'm filled to be emptied again the seed I've received I will sow © 2008 Hillsong Music Publishing (Admin. -

Jars of Clay “20”

JARS OF CLAY “20” Looking Back, Facing Forward: 20 Soundtracks Jars of Clay’s 20-Year Celebration with New Interpretations of Fan-Selected Favorites To celebrate 20 years together as a band, Jars of Clay has taken 2014 to throw themselves a yearlong birthday party. Not only have they spent the year performing a series of online Stageit concerts commemorating their previous albums, but they have also crafted a uniquely special, fan-curated retrospective double album of re-recorded favorites appropriately titled 20. As the band reflected on their previous twenty years, they wanted to mark the milestone in a way that seemed true to the spirit they had cultivated within their first two decades. During one of their early online Stageit concerts, Jars of Clay multi-instrumentalist Stephen Mason noticed, “There were some songs that were surprisingly hitting a really strong emotional chord in me because I had missed them the first time around.” It is this second-time-around sentiment that sparked the initial idea for 20. Not wanting to just compile their own favorite songs for an uninspired greatest hits package, the band looked for an opportunity to once again serve and thank their fans in a genuine, tangible way. They decided on the retrospective re-recording approach and as keyboardist Charlie Lowell explains, “We wanted to really honor the fans by letting them choose the songs.” By allowing the fans to say which songs they would do and allowing themselves to decide how they would do them, the adventurous 20 ends up feeling both nostalgic and now, simultaneously looking back and facing forward. -

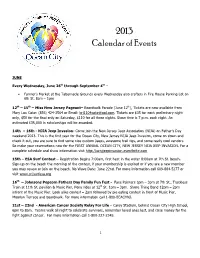

2013 Calendar of Events

2013 Calendar of Events JUNE Every Wednesday, June 26th through September 4th – • Farmer’s Market at the Tabernacle Grounds every Wednesday also crafters in Fire House Parking Lot on 6th St. 8am – 1pm 12th – 15th – Miss New Jersey Pageant– Boardwalk Parade (June 12th), Tickets are now available from Mary Lou Cake: (856) 424-3564 or Email: [email protected]. Tickets are $35 for each preliminary night only, $50 for the final only on Saturday, $110 for all three nights. Show time is 7 p.m. each night. An estimated $35,000 in scholarships will be awarded. 14th – 16th - NJJA Jeep Invasion- Come join the New Jersey Jeep Association (NJJA) on Father's Day weekend 2013. This is the first year for the Ocean City, New Jersey NJJA Jeep Invasion, come on down and check it out, you are sure to find some nice custom Jeeps, awesome trail rigs, and some really cool vendors. So make your reservations now for the FIRST ANNUAL OCEAN CITY, NEW JERSEY NJJA JEEP INVASION. For a complete schedule and show information visit http://ocnjjeepinvasion.eventbrite.com 15th – ESA Surf Contest – Registration begins 7:00am, first heat in the water 8:00am at 7th St. beach. Sign-up on the beach the morning of the contest, if your membership is expired or if you are a new member you may renew or join on the beach. No Wave Date: June 22nd. For more information call 609-884-5277 or visit www.snjsurfesa.org 16th – Johnsons Popcorn Fathers Day Family Fun Fest - Face Painters 1pm – 3pm at 7th St., Trackless Train at 11th St. -

Ide — Intsormil

|\¡0 E.A.P. 201(28) IDE — INTSORMIL BIBLIOTECA Wllsnv „ ESCUELA AQniC'OLA pi °PEWOi January 2001 «ÿBTADO *MEF»°ANA TEei/C<GAiOAT ,._S3 Publication 01-1 •'Ui,uu«AS Newsletter of the Sorghum/Millet Collaborative Research Support Program colleagues inAfrica, Central America, ICRISAT and C-ommei/uts from, the t>lreetor other parts of the world. We look forward to closer J relationships with our colleagues in the regional networks, ROCAFREMI, ROCARS, ASARECA, Greetings to all INTSORMIL collaborating scientists and ECARSAM, SMINET, and CLAIS (Central America). friends of INTSORMIL in this new year of 2001. As we We see this new year of 2001 as a propitious time for us reflect back, we are truly appreciative of the hard work all to work together in promoting sorghum and pearl and dedication which each person has given to help mold millet as the commercial food and feed grain crops of the INTSORMIL into the excellent program that it is today. future in the semi-arid tropics. Now we are looking to the future and are preparing the John M. Yohe program for continuing its work into the first decade of the 21st Century. We are moving forward with some significant changes and a loss of familiar faces which helped to make INTSORMIL such a distinctive program. We lost a great friend and sorghum research scientist Inside Page through the death of Dr. John Axtell. In addition, the John Axtell 2 program has experienced the loss of breeding, entomology, pathology, and physiology expertise with the Retirements 3 retirements of Professor David Andrews, Dr. -

2018–2019 Year in Review

MOREHEAD-CAIN YEAR IN REVIEW 2018–2019 YEAR IN REVIEW 2018–2019 MOREHEAD-CAIN FOUNDATION POST OFFICE BOX 690 CHAPEL HILL, NC 27514-0690 moreheadcain.org @moreheadcain WITH PURPOSE. WITH PROMISE. YEAR IN REVIEW 2018–2019 CONTENTS From the Director 1 Morehead-Cain Foundation Board of Trustees 3 Morehead-Cain Day of Giving: November 19, 2018 4 Are You a Morehead-Cain Partner? 6 Honor Roll of Giving 8 Graduate and Professional School Donors 8 Alumni and Scholar Donors by Class 8 2018 Alumni Forum Sponsors 20 Friends of the Program 22 Morehead-Cain Staff Donors 27 Parents of Alumni and Scholars 27 Parents’ Perspective: Sandy McKenzie and Larry Nabatoff 29 Corporation and Foundation Donors 30 Morehead-Cain Scholarship Fund Board of Directors 32 Cover: James Dean ’89 delivers his SEVEN Talk in Memorial Hall on the Carolina campus at the Eighth Triennial Morehead-Cain Alumni Forum This page: SEVEN Speakers and Forum Co-Chairs on the Memorial Hall stage A Message from the Fund Board Chair 33 Morehead-Cain Benefactors 82 The Year in Review 2018–2019 36 Scholar Impact at Carolina 85 The Morehead-Cain Selection Process 61 Class of 2019 109 Selection Process at a Glance 62 Class of 2020 139 Professional Readers 63 Class of 2021 145 Regional Selection Committee 63 Class of 2022 151 Central Selection Committee 64 Class of 2023 158 British Selection Process 66 Morehead-Cain Staff 166 Canadian Selection Process 66 Special Thanks New Nominating Schools 67 The Summer Enrichment Program 69 The John Motley Morehead Society 76 John Motley Morehead Society Spotlight: Anne and Alex Lassiter ’10 78 #TakeoverTuesday 81 FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, I find it hard to summarize the past year at Carolina and Morehead-Cain. -

Wholemegillah

Congregation Beth Shalom Rodfe Zedek The WholeMegillah September & October 2018 21 Elul, 5778 – 22 Heshvan, 5779 Inside this issue A Story for the High Holy Days by Allan Appel pgs 10–14 Letter from our new president, Brad Jubelirer........................4–5 High Holy Days schedule and reflections.......................6–7 Alison Miller’s journey leads her to the Holy Scrollers.....14–15 Exhibition of the underwater photography of David Zeleznik................17–18 Melinda Alcosser visits Guatemala........................19–20 www.cbsrz.org Dakota Udoff guarding the entrance to CBSRZ T H A N K Y O U IN THIS ISSUE to the following donors from 6/6/2018 to 8/3/2018 2nd Century Campaign Meg Magida: in memory of Nat Magida William & Janet Brownstein Christine & Robert Mangiafico: in memory of From Our Rabbi John Schwolsky & Elizabeth Storch: in memory of Maxine Klein's bat mitzvah 3 Evelyn and Irving Schwolsky and Alan & Florence Storch Helen McNutt: in memory of David Klar Arthur & Marcia Meyers: in memory of Linda Chesed Fund Rabbi Marci Bellows Sherman President's Letter 860-526-8920 Ray & Liz Archambault: in memory of Linda Sherman Norman Needleman: in memory of Ann Needleman [email protected] Eric & Barbara Infeld: in memory of Linda Sherman 4–5 Harvey Payton & Lori Shafner: in memory of Food/Beverage Fund Linda Sherman Cantor Belinda Brennan Eric & Barbara Infeld: in memory of David Klar Michael & Susan Peck: in memory of David and High Holy Days Cantor Educator Arthur & Marcia Meyers Miriam Klar 860-526-8920 Andrea Pollack &