Notes on Whitehill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

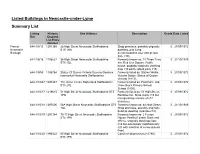

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-Under-Lyme Summary List

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-under-Lyme Summary List Listing Historic Site Address Description Grade Date Listed Ref. England List Entry Number Former 644-1/8/15 1291369 28 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Shop premises, possibly originally II 27/09/1972 Newcastle ST5 1RA dwelling, with living Borough accommodation over and at rear (late c18). 644-1/8/16 1196521 36 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 14 Three Tuns II 21/10/1949 ST5 1QL Inn, Red Lion Square. Public house, probably originally dwelling (late c16 partly rebuilt early c19). 644-1/9/55 1196764 Statue Of Queen Victoria Queens Gardens Formerly listed as: Station Walks, II 27/09/1972 Ironmarket Newcastle Staffordshire Victoria Statue. Statue of Queen Victoria (1913). 644-1/10/47 1297487 The Orme Centre Higherland Staffordshire Formerly listed as: Pool Dam, Old II 27/09/1972 ST5 2TE Orme Boy's Primary School. School (1850). 644-1/10/17 1219615 51 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly listed as: 51 High Street, II 27/09/1972 1PN Rainbow Inn. Shop (early c19 but incorporating remains of c17 structure). 644-1/10/18 1297606 56A High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly known as: 44 High Street. II 21/10/1949 1QL Shop premises, possibly originally build as dwelling (mid-late c18). 644-1/10/19 1291384 75-77 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 2 Fenton II 27/09/1972 ST5 1PN House, Penkhull street. Bank and offices, originally dwellings (late c18 but extensively modified early c20 with insertion of a new ground floor). 644-1/10/20 1196522 85 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Commercial premises (c1790). -

Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan

Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council October 2020 Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Prepared for: Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council AECOM Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Table of Contents 1. Foreword ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 6 3. Contextual analysis ......................................................................................... 9 Kidsgrove Town Deal Investment Area ............................................................................................................. 10 Kidsgrove’s assets and strengths .................................................................................................................... 11 Challenges facing the town ............................................................................................................................. 15 Key opportunities for the town ......................................................................................................................... 19 4. Strategy ......................................................................................................... 24 Vision ............................................................................................................................................................ -

North Housing Market Area Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessment

North Housing Market Area Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Needs Assessment Final report Philip Brown and Lisa Hunt Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit University of Salford Pat Niner Centre for Urban and Regional Studies University of Birmingham December 2007 2 About the Authors Philip Brown and Lisa Hunt are Research Fellows in the Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU) at the University of Salford. Pat Niner is a Senior Lecturer in the Centre for Urban and Regional Studies (CURS) at the University of Birmingham The Salford Housing & Urban Studies Unit is a dedicated multi-disciplinary research and consultancy unit providing a range of services relating to housing and urban management to public and private sector clients. The Unit brings together researchers drawn from a range of disciplines including: social policy, housing management, urban geography, environmental management, psychology, social care and social work. Study Team Core team members: Community Interviewers: Dr Philip Brown Sharon Finney Dr Lisa Hunt Tracey Finney Pat Niner Violet Frost Jenna Condie Joe Hurn Ann Smith Steering Group Karen Bates Staffordshire Moorlands District Council Abid Razaq Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Philip Somerfield East Staffordshire Borough Council Eleanor Taylor Stoke-on-Trent City Council Stephen Ward Stafford Borough Council 3 4 Acknowledgements This study was greatly dependent upon the time, expertise and contributions of a number of individuals and organisations, without whom the study could not have been completed. Members of the project Steering Group provided guidance and assistance throughout the project and thanks must go to all of them for their support to the study team. Special thanks are also due to all those who took the time to participate in the study, helped organise the fieldwork and provided invaluable information and support in the production of this report. -

Newcastle Way Guide Booklet

The Newcastle Way Walk from Mow Cop to Market Drayton The Newcastle Way Introduction: ironstone, coal and clay. 40 kilometres in easy stages Mow Cop The Newcastle Way is a long distance walking route on public rights of way through the Borough of Newcastle under-Lyme. It links the Pages 2-3 Staffordshire Way at Mow Cop with the Shropshire Union Canal towpath at Market Drayton, a distance of approximately 40km (25 miles) on the map. To follow the whole route using Ordnance Survey maps you will need Kidsgrove Bank 1:25000 scale Explorer sheets 258 The Potteries and Newcastle, 243 Market Drayton, and 257 Whitchurch. Pages 4-5 Changing Landscape. Red Street This is a fascinating walk at any time of year, with challenging terrain and Pages 6-7 a constantly changing landscape. From rough moorland scenery around Mow Cop the Way passes through the relics of coal mining, iron furnaces and brick making to rich farming country around Madeley. Then it's up Black Bank along the sandstone ridges of Maer and Ashley and across the wide open Finney Green clump - half way there spaces of Blore Heath to Almington and the 'Shroppie'. Along the route Pages 8-9 the landmarks on the horizon start to become very familiar, with frequent views into Cheshire, west to the Shropshire Hills and south as far as Cannock Chase. Madeley Walk in easy stages. Pages 10-11 In this booklet the Newcastle Way has been divided into seven sections for ease of reference and for those who would prefer to walk the route in easy stages. -

Housing Development Monitoring Report 2008

Newcastle-under-Lyme Housing Development Monitoring Report 2008 Borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme Housing Development Monitoring Report 2008 Page CONTENTS i LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND PLANS ii INTRODUCTION: 1 PART 1: HOUSING DEVELOPMENT IN 2007-2008: 1 1.1 DWELLINGS COMPLETED 1 1.2 DWELLINGS UNDER CONSTRUCTION 2 1.3 PLANNING PERMISSIONS GRANTED 3 1.4 LARGE HOUSING SITES 4 1.5 SMALL HOUSING SITES 7 PART 2: THE REGIONAL SPATIAL STRATEGY 2006-2026: 9 2.1 INTRODUCTION 9 2.2 PROGRESS TOWARDS MEETING REGIONAL SPATIAL STRATEGY ALLOCATION 2006-2026 9 PART 3: OTHER HOUSING DEVELOPMENT ISSUES: 13 3.1 DWELLINGS COMPLETED ON ‘WINDFALL’ SITES 13 3.2 DWELLINGS PROVIDED BY CONVERSION AND CHANGE OF USE: 15 3.3 PREVIOUS USE OF HOUSING SITES - BROWNFIELD/GREENFIELD ISSUE: 15 3.4 ANALYSIS OF HOUSE PRICES: 19 3.5 AFFORDABLE HOUSING 23 3.6 DENSITY OF NEW DEVELOPMENT 25 3.7 DEMOLITIONS 28 3.8 DWELLING TYPES COMPLETED 29 PART 4: THE RSS AND THE STATUTORY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 31 PART 5: HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY POSITION STATEMENT AT 1.4.08 32 i List of Tables: Page TABLE 1 Dwellings completed 1.4.07 to 31.3.08 1 TABLE 2 Dwellings under construction at 31st March 2008 2 TABLE 3 Full/Detailed Planning Permissions issued in 2007/08 - by type of housing and sector: 3 TABLE 4a Large sites under construction between 1st Apr 07 - 31st Mar 2008 4 TABLE 4b Progress update on ‘large’ sites ‘under construction’ in the Borough at 31st March 08 5 TABLE 5 Large sites where housebuilding had not commenced at 31st Mar 08 7 TABLE 6 New dwellings/conversions completed 1.4.06 to 31.3.08 9 TABLE 7 New dwellings commenced, completed and under construction 1.4.98 to 31.3.08 10 TABLE 8 New dwellings/conversions with outstanding planning permission at 1st Apr 08 11 TABLE 9 New dwellings/conversions completed, under construction, with outstanding planning permission and permitted subject to a S.106 Agreement at 1st Apr 08. -

Guide Book.Cdr

The Newcastle Way Walk from Mow Cop to Market Drayton The Newcastle Way Introduction: ironstone, coal and clay. 40 kilometres in easy stages Mow Cop The Newcastle Way is a long distance walking route on public rights of way through the Borough of Newcastle under-Lyme. It links the Pages 2-3 Staffordshire Way at Mow Cop with the Shropshire Union Canal towpath at Market Drayton, a distance of approximately 40km (25 miles) on the map. To follow the whole route using Ordnance Survey maps you will need Kidsgrove Bank 1:25000 scale Explorer sheets 258 The Potteries and Newcastle, 243 Market Drayton, and 257 Whitchurch. Pages 4-5 Changing Landscape. Red Street This is a fascinating walk at any time of year, with challenging terrain and Pages 6-7 a constantly changing landscape. From rough moorland scenery around Mow Cop the Way passes through the relics of coal mining, iron furnaces and brick making to rich farming country around Madeley. Then it's up Black Bank along the sandstone ridges of Maer and Ashley and across the wide open Finney Green clump - half way there spaces of Blore Heath to Almington and the 'Shroppie'. Along the route Pages 8-9 the landmarks on the horizon start to become very familiar, with frequent views into Cheshire, west to the Shropshire Hills and south as far as Cannock Chase. Madeley Walk in easy stages. Pages 10-11 In this booklet the Newcastle Way has been divided into seven sections for ease of reference and for those who would prefer to walk the route in easy stages. -

Strategic Housing Market Assessment Stoke-On-Trent City Council and Newcastle-Under-Lyme Borough Council

Strategic Housing Market Assessment Stoke-on-Trent City Council and Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council July 2015 Contents Executive Summary i 1. Introduction 5 2. Housing Market Area Geography 14 3. Housing Stock 19 4. Demographic and Economic Drivers of the Market 38 5. Market Signals 77 6. Alternative Projections of Housing Need 117 7. Affordable Housing Need 158 8. Housing Requirements of Specific Groups 184 9. Study Conclusions and the Objective Assessment of Need 216 Appendix 1: Stakeholder Workshop 228 Appendix 2: Defining Housing Market Area Geographies 231 Appendix 3: Objectively Assessed Need in Neighbouring Authorities 232 Appendix 4: Edge Analytics Modelling Assumption Note 236 Appendix 5: Modelled Change in Households by Size 237 Appendix 6: Affordable Housing Needs Assessment 242 July 2015 Executive Summary 1. This report presents a new Strategic Housing Market Assessment (SHMA) for Stoke-on- Trent and Newcastle-under-Lyme. The research has been undertaken by Turley in partnership with specialist demographic consultancy Edge Analytics. 2. The preparation of a new joint SHMA for Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stoke-on-Trent will form a key part of the evidence base for the new Joint Local Plan, identifying a range of suitable objectively assessed housing need targets in conformity with guidance outlined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and Planning Practice Guidance (PPG). 3. The PPG highlights the importance of considering needs across housing market area geographies, recognising that this often extends beyond local authority boundaries. This report includes a review of a range of spatial indicators – including trends in migration, house prices and commuting – to confirm that Newcastle-under-Lyme and Stoke-on- Trent can jointly be considered to represent a single housing market area, for the purposes of assessing housing need in line with the PPG. -

To the Chair and Members of the LICENSING COMMITTEE

Miss J Cleary To the Chair and Members 742227 of the JEC/EVB LICENSING COMMITTEE 30 January 2009 Dear Sir/Madam A meeting of the LICENSING COMMITTEE will be held in the COUNCIL CHAMBER, CIVIC OFFICES, MERRIAL STREET, NEWCASTLE on THURSDAY, 12 FEBRUARY 2009 at 7.00pm AGENDA 1. Minutes from meeting held on 12 November 2007 (yellow paper). 2. To consider the reports of your Officers (copies attached – white paper). 3. To consider any business which is urgent within the meaning of Section 100B(4) of the Local Government Act 1972. Yours faithfully P W CLISBY Head of Central Services Officers will be in attendance prior to the meeting for informal discussions on agenda items. NEWCASTLE-UNDER-LYME BOROUGH COUNCIL REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT TEAM TO THE LICENSING COMMITTEE 12 February 2009 1. LICENSING ACT 2003 – STATEMENT OF LICENSING POLICY Purpose For Members to consider whether the Special Saturation Policy that was agreed at the meeting held on 21 August 2008 is still needed. Recommendations (a) That subject to the evidence provided, the Special Saturation Policy remain on its existing boundaries as detailed in the Licensing Policy for the next 12 months. (b) That the remit of the Licensing Liaison Group be expanded to allow consideration of the Licensing and Gambling Polices. 1. Background 1.1 At the meeting of the Licensing Committee held on 22 August 2007, Members approved the draft Statement of Licensing Policy for consultation between the beginning of September and the 12 October 2007. During that period a consultation exercise was carried out with the statutory consultees, the Police, the Fire Authority and national organisations representing the licensing trade and also organisations representing local businesses and residents. -

Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Report

Level 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment Final Report October 2019 www.jbaconsulting.com Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED JBA Project Manager Hannah Hogan BA (hons) MA IWA-MCIWEM C.WEM CEnv The Library St Philips Courtyard Church Hill Coleshill Warwickshire B46 3AD Revision History Revision Ref / Date Amendments Issued to Issued 01/02/2019 Draft Report Karl Conyon, Growth & Prosperity Directorate, Stoke-on-Trent City Council 15/04/2019 Second Draft Report Karl Conyon Growth & Prosperity Directorate, Stoke-on-Trent City Council 04/10/2019 Final Report Jemma March, Planning Policy, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council Contract This report describes work commissioned by Karl Conyon on behalf of Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council via Faithful & Gould in accordance with the PAGABO professional framework services on the 20th July 2018. Hannah Hogan, Freyja Scarborough and Erin Holroyd of JBA Consulting carried out this work. Prepared by .................................................. Freyja Scarborough BSc MSc Analyst ....................................................................... Erin Holroyd BSc Technical Assistant Reviewed by ................................................. Hannah Hogan MA IWA-MCIWEM C.WEM CENV Chartered Senior Analyst …………….................................................... Hannah Coogan BSc MCIWEM C.WEM Technical Director Purpose This document has been prepared as a Final Report for Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council. JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability -

Property Auction Catalogue Property Auctions Online Only Sale – Pre-Registration Required

Online Only Sale – pre-registration required Monday 22nd February, 6.30pm start Property auction catalogue Property auctions Online Only Sale – pre-registration required SALE DATE CLOSING DATE 29th March 19th February 10th May 2nd April 14th June 7th May 26th July 18th June 20th September 13th August 25th October 17th September 29th November 22nd October All auctions start at 6.30pm Freehold & Leasehold Lots offered in conjunction with... 02 View property auction results at buttersjohnbee.com The region’s number 1 property auctioneer John Hand Donna Fern Rob Oulton Auction Manager Auction Negotiator Auctioneer Here at butters john bee we have over 150 years’ experience of selling property at auction. For the time being and foreseeable future our auctions will remain ONLINE ONLY SALES. We are doing our utmost to keep things on track so we can continue to give you the best service, and we are having great success with our Internet Sales. Obviously we have always offered remote bidding at all our auctions, and I’m pleased to say that we are now working in partnership with EIG (Essential Information Group) who will be hosting our live sale as well as the Legal Pack page, streamlining the service we are able to offer and making it much easier for you to register to bid. This sale will run in exactly the same the market nationally, as all Auctioneers format as usual, as in we will have our are reverting to online sales, so we are auctioneer on the podium offering each following suit so you don’t miss out. -

Joint Local Plan Preferred Options Consultation Housing Technical

Joint Local Plan Preferred Options Consultation Housing Technical Paper – December 2017 This paper sets out the technical evidence to support the information on housing development that is presented in the Joint Local Plan Preferred Options Consultation document. 1.0 Housing Requirement 1.1 The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) states that Local Authorities should ‘use their evidence base to ensure that their Local Plan meets the full, objectively assessed needs (OAN) for market and affordable housing in the housing market area, as far as is consistent with the policies set out in this Framework, including identifying key sites which are critical to the delivery of the housing strategy over the plan period;’ The NPPF (para 14) also states, for plan-making, that Local Authorities should positively seek opportunities to meet the development needs of their area. 1.2 The Strategic Options Consultation document set out four growth options that were being considered for the Joint Local Plan to deliver, as follows: Table 1 - Strategic Options Growth Options Growth Description: New Houses New Houses Option: Required Each Required 2013- Year: 33: Carry forward the existing levels A of growth set out in the Core 855 17,100 Spatial Strategy Support our natural population B 1,084 21,680 growth Supporting our economic growth C 1,390 27,800 (OAN) Maximising our economic D 1,814 36,280 potential 1 1.3 It was stated in the Strategic Options Consultation document that Options A and B were unlikely to be compliant with national policy1. This level of growth is well below that recommended in the SHMA2 as the objectively assessed need. -

John Henry Clive, Born 1781, but Certain Parish Registers Are Missing at That Date, and I Can Only State What Tradition Hands Down to Us

I. i' i ! i 2, I 1· I 11ve John Henrvwl C I 1781-1853 of North Staffordshire and his Descendants. BY PERC-Y~ \\~. L. .J..~D'"~{s .J,... ....-1..~, .l ( A Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London) Author of "A History of the Adams Family of North Staffordshire" "The Douglas Family of Morton in Nithsdal,e" •'Notes on N ortk Staffordshire Families " "The Jukes Family of Cound, Sal.op" Contributor to ..Memorials of Old Staffordshire " Sometime Hon. Editor & Sec. of " The Staffordshire Parish Registers Society," dk. I Printed at the Press of l G. T. BAGGULEY at NEWCASTLE in the County of Stafford 1947 I Every generation needs regeneration- C. H. SPURGEON : "Salt Cellars" ~.......- ....,_;_ ~' ., ~,'..~ ,r- . .,--.,.. ~~.. :-_·:· 1781) (1853 DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF ROBERT CLEMENT AND MARY CLIVE FOREWORD Some ten years before the death of my parents' old friend, Col. Robert Clement Clive, of Graven hunger, W oore, he handed over to me a mass offamily papers, knowing that I had written several f amity histories in my spare moments. I looked through them, but being very busy at the time nothing materialised, and I returned the papers. I, however, did form a scrap of a pedigree, and after his death I passed what I had made out to his son, Col. Harry Clive, of Willoughbridge, who was so much interested that in odd moments I was encouraged to add a good deal more to the account of the family until I was astonished to find it had run into a great many pages.