What Is Atonality (1930)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

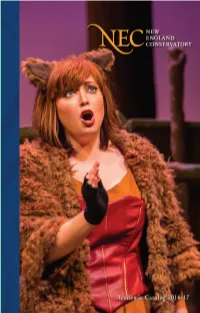

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

The Study of the Relationship Between Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily

THE STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ARNOLD SCHOENBERG AND WASSILY KANDINSKY DURING SCHOENBERG’S EXPRESSIONIST PERIOD D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sohee Kim, B.M., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2010 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Donald Harris, Advisor Professor Jan Radzynski Professor Arved Mark Ashby Copyright by Sohee Kim 2010 ABSTRACT Expressionism was a radical form of art at the start of twentieth century, totally different from previous norms of artistic expression. It is related to extremely emotional states of mind such as distress, agony, and anxiety. One of the most characteristic aspects of expressionism is the destruction of artistic boundaries in the arts. The expressionists approach the unified artistic entity with a point of view to influence the human subconscious. At that time, the expressionists were active in many arts. In this context, Wassily Kandinsky had a strong influence on Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg‟s attention to expressionism in music is related to personal tragedies such as his marital crisis. Schoenberg solved the issues of extremely emotional content with atonality, and devoted himself to painting works such as „Visions‟ that show his anger and uneasiness. He focused on the expression of psychological depth related to Unconscious. Both Schoenberg and Kandinsky gained their most significant artistic development almost at the same time while struggling to find their own voices, that is, their inner necessity, within an indifferent social environment. Both men were also profound theorists who liked to explore all kinds of possibilities and approached human consciousness to find their visions from the inner world. -

Alban Berg's Filmic Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn, "Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ALBAN BERG’S FILMIC MUSIC: INTENTIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF THE FILM MUSIC INTERLUDE IN THE OPERA LULU A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith A.B., Smith College, 1993 A.M., Smith College, 1995 M.L.I.S., Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1999 May 2002 ©Copyright 2002 Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to express gratitude to my wonderful committee for working so well together and for their suggestions and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Jan Herlinger, my dissertation advisor, for his insightful guidance, care and precision in editing my written prose and translations, and open mindedness. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation. -

Unit 8 Practice Test

Name ___________________________________ Date __________ Unit 8 Practice Test Part 1: Multiple Choice 1) In music, the early twentieth century was a time of A) the continuation of old forms B) stagnation C) revolt and change D) disinterest 2) Which of the following statements is not true? A) Twentieth-century music follows the same general principles of musical structure as earlier periods. B) After 1900 each musical composition is more likely to have a unique system of pitch relationships, rather than be organized around a central tone. C) Twentieth-century music relies less on pre-established relationships and expectations. D) The years following 1900 saw more fundamental changes in the language of music than any time since the beginning of the baroque era. 3) Which statement about composers of the 20th century is not true? A) Composers were asking the question "How can we make the music from the past better?" B) Some composers trying to distance themselves from the past. C) Some composers tried to return to some aspect of the past, especially the Classical Period. D) Composers had ambivalent attitudes toward the musical past. 4) Which statement concerning 20th century music is not true? A) Art music was becoming more relevant in day-to-day life. B) Composers whose music has become more and more complex have widened the gap between art and popular music. C) There was a widening gap between art music and popular music. D) Popular music especially jazz, country and rock became the central musical focus of the majority of people in the Western world. -

Chapter 28: Neoclassicism and Twelve-Tone Music: 1915–50 I

Chapter 28: Neoclassicism and Twelve-Tone Music: 1915–50 I. Introduction A. The carnage of World War I shattered the ideals of Romanticism. II. The First World War and its impact on the arts A. The wave of shock produced by the Great War reverberated in the arts. A preference emerged for spoken over sung, reason over feeling, and reportage over poetry. III. Neoclassicism A. After shocking the world with the scandalous Rite of Spring (and a few other works), Stravinsky went in an entirely different direction in 1923 with his Octet for woodwinds. This work marks the beginning of a new style: Neoclassicism. 1. This style was marked by “objectivity,” which composers conveyed by bringing back eighteenth-century gestures, although it could include aspects of Baroque, popular music of the 1920s, and even Tchaikovsky. IV. Igor Stravinsky’s Neoclassical path A. At the end of World War I (1918), Stravinsky composed Histoire du soldat. 1. The ensemble was small, by comparison with the Rite, and featured instruments associated with jazz. 2. Soon thereafter, Diaghilev and his recent choreographer Massine teamed up with Stravinsky to do a work based on eighteenth-century music: Pulcinella. 3. These two works (Histoire du soldat and Pulcinella) were stage works, but Stravinsky soon looked to instrumental pieces for this developing new style. 4. The raw aspect of Rite was noted early on. This aspect connects it with the lack of Romanticism (“renunciation of ‘sauce’”) noted in the later works. 5. In the 1920s, irony triumphed over sincerity as an artistic aim. B. The music of Stravinsky’s Octet 1. -

Twelve-Tone Serialism: Exploring the Works of Anton Webern James P

University of San Diego Digital USD Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-19-2015 Twelve-tone Serialism: Exploring the Works of Anton Webern James P. Kinney University of San Diego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/honors_theses Part of the Music Theory Commons Digital USD Citation Kinney, James P., "Twelve-tone Serialism: Exploring the Works of Anton Webern" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 1. https://digital.sandiego.edu/honors_theses/1 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Twelve-tone Serialism: Exploring the Works of Anton Webern ______________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty and the Honors Program Of the University of San Diego ______________________ By James Patrick Kinney Music 2015 Introduction Whenever I tell people I am double majoring in mathematics and music, I usually get one of two responses: either “I’ve heard those two are very similar” or “Really? Wow, those are total opposites!” The truth is that mathematics and music have much more in common than most people, including me, understand. There have been at least two books written as extensions of lecture notes for university classes about this connection between math and music. One was written by David Wright at Washington University in St. Louis, and he introduces the book by saying “It has been observed that mathematics is the most abstract of the sciences, music the most abstract of the arts” and references both Pythagoras and J.S. -

The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism As Seen in the Operas Performed Between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’S Jonny Spielt Auf

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 6-10-2020 The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf Nicole Fassold Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Fassold, Nicole, "The Concurrent Prevalence of Modernism and Romanticism as seen in the Operas Performed between the World Wars and Exemplified in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5301. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5301 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE CONCURRENT PREVALENCE OF MODERNISM AND ROMANTICISM AS SEEN IN THE OPERAS PERFORMED BETWEEN THE WORLD WARS AND EXEMPLIFIED IN ERNST KRENEK’S JONNY SPIELT AUF A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Nicole Fassold B.M., Colorado State University, 2015 M.M., University of Delaware, 2017 August 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the professors and panel members that have guided me throughout my Doctoral studies as well as to my parents and sister, my family all over the world, my friends, and my incredible husband for their unending support and encouragement. -

The Elements of Contemporary Turkish Composers' Solo Piano

International Education Studies; Vol. 14, No. 3; 2021 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Elements of Contemporary Turkish Composers’ Solo Piano Works Used in Piano Education Sirin A. Demirci1 & Eda Nergiz2 1 Education Faculty, Music Education Department, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey 2 State Conservatory Music Department, Giresun University, Turkey Correspondence: Sirin A. Demirci, Education Faculty, Music Education Department, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 19, 2020 Accepted: November 6, 2020 Online Published: February 24, 2021 doi:10.5539/ies.v14n3p105 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n3p105 Abstract It is thought that to be successful in piano education it is important to understand how composers composed their solo piano works. In order to understand contemporary music, it is considered that the definition of today’s changing music understanding is possible with a closer examination of the ideas of contemporary composers about their artistic productions. For this reason, the qualitative research method was adopted in this study and the data obtained from the semi-structured interviews with 7 Turkish contemporary composers were analyzed by creating codes and themes with “Nvivo11 Qualitative Data Analysis Program”. The results obtained are musical elements of currents, styles, techniques, composers and genres that are influenced by contemporary Turkish composers’ solo piano works used in piano education. In total, 9 currents like Fluxus and New Complexity, 3 styles like Claudio Monteverdi, 5 techniques like Spectral Music and Polymodality, 5 composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Guillaume de Machaut and 9 genres like Turkish Folk Music and Traditional Greek are reached. -

Soe V Modern Theories of Tonality

SOEV MODERN THEORIES OF TONALITY APPROVE )D: fe so r~ 0ij o Pr o linor Professor Director 0 he part-men Divi ussic Dea f the (.-ra te Division SOME MODERN THEORIES OF TONALITY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State Teachers College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Dorothy Robert, B. M. Denton, Texas January, 1946 138028 138928 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES . * * . * * * * .*. V Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . Exhaustion of iajor-Minor Tonality Signs of Revolution Composer and Audience New Founcations of Music Four Principal Theories Definitions of Tonality II. PRESENTATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF THE PRINCIPAL AUTHORITIES AND THEORISTS . 9 Hermann v. Helwholtz Adele Katt Arnold Schoenberg Paul Hindemith Joseph Yasser Application of Theories III. HERMANN v. HEL IOLTZ . .. 12 Physics of Sound Physiology of Hearing Aesthetic Approach to Music IV. ADELE T. KATZ . 16 Heinrich Schenker Challengers of Musical Tradition Schenker 's Theory Basic Structure and Prolongation The Structural Top Voice The Cadence Polytonality and Atonality Criticism iii Chapter page V. ARNOLD SCHOENBERG ... .... ..... 29 The Crisis before Schoenberg Schoenberg's Twelve-tone System Reactions to Schoenberg's Approach Schoenberg's Influence Criticism and Reinterpretation of Schoenberg's System VI. PAUL HINDEMITH . 39 Derivation of the Chromatic Scale Invertibility of Intervals Melodic and Harmonic Forces of Intervals Tonal Activity Comparison of Traditional Harmony with Hindemith' asSystem Atonality and Polytonality Summary VII. JOSEPH YASSER ................ 54 Historical Development of Scale Systems Relativity of Musical Terms Construction of the Infra-diatonic and Diatonic Systems Construction of the Supra-diatonic System The Supra-diatonic Scale The Supra-diatonic Modes The Supra-diatonic Intervals Supra-diatonic Chords Supra-tonality Anticipated in Contem- porary Music Definition of Tonality Atonality Vetsus Supra-tonality Historical Considerations and Prophecies Possible Objections to Yasser's System VIII. -

I ROW CONSTRUCTION and ACCOMPANIMENT in LUIGI

ROW CONSTRUCTION AND ACCOMPANIMENT IN LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA’S IL PRIGIONIERO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music by DORI WAGGONER Dr. Neil Minturn, Thesis Supervisor December 2007 i The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled ROW CONSTRUCTION AND ACCOMPANIMENT IN LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA’S IL PRIGIIONIERO presented by Dori Waggoner, a candidate for the degree of master of music, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Neil Minturn Professor Stefan Freund Professor Rusty Jones Professor Thomas McKenney Professor Nancy West ii Thank you to my husband and son. Without your support, patience, and understanding, none of this would have been possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the encouragement and advice of Dr. Neil Minturn, this document would not exist. I would like to thank him for encouraging me to listen to the music and to let it guide me through the analysis. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………...….ii LIST OF EXAMPLES……………………………………………………………...iv ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………….……..vi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….1 Compositional Influences Plot Summary 2. ROW CONSTRUCTION……………………………………………………..9 The Prayer Row The Hope Row The Freedom Row The Chorus Row The Fratello Motif/Row 3. ACCOMPANIMENT………...……………………………………….…….26 Accompaniment that Doubles the Vocal Line Accompaniment by Same Row Accompaniment by Different Row Accompaniment with Chromaticism Accompaniment with Octatonicism 4. CONCLUSIONS……………………………………………………………35 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………..……….39 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES Example Page 1. Volo di Notte , mm. 382–387………………………………………………….….….6 2. Prayer Row……………………………………………………….…………….…..11 3.