Interview of Robert Boyce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemistry at Shawnee State University

How We Stand Out: • Chemistry Students have been accepted into prestigious summer research programs at the University of California, Irvine; The University of North Dakota, and The University of Cincinnati. Shawnee • We have an active Chemistry club that invites speakers to campus, gets involved in our State University community, and organizes social activities. Department of Natural Sciences 740.351.3456 Chemistry at [email protected] College of Arts & Sciences Office of Admission The College of Arts & Sciences at Shawnee State 740.351.4SSU (4778) or 800.959.2SSU (2778) Shawnee State [email protected] University includes the Vern Riffe Center for the Arts, five academic departments, 34 baccalaureate Shawnee State University degree programs, 30 minors, and five associate 940 Second Street | Portsmouth, Ohio 45662 University degree programs. The College also includes a Master www.shawnee.edu of Mathematical Sciences degree. We invite you to explore opportunities available through our diverse areas of study. Chemistry at Shawnee How We Stand Out: A degree in chemistry from Shawnee State University • Four faculty members with Ph.D’s in Chemistry. State University prepares you for a career Shawnee State designed its Chemistry program using • Hands-on access to all instrumentation in the guidelines set forth by the American Chemical Society. It is a in science. Our graduates have found jobs department, including NMR, FTIR, GC, GC- rigorous, comprehensive program that contains course work MS, UV-VIS, AA, and a Bomb Calorimeter. working for chemical companies, as well in all areas of modern Chemistry: Analytical, Biochemistry, as continuing their education in graduate, Inorganic, Organic, and Physical Chemistry. -

2020 Scenic Scioto Heritage Trail

2020 Scenic Scioto Heritage Trail Corridor Management Plan (CMP) Ohio Department of Transportation Submitted January 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Designation Summary B. Byway Route Map II. BYWAY STRATEGIC PLAN 3 A. Vision, Mission and Beliefs B. Accomplishments since last CMP C. Goals, Objectives, and Action Plans III. BYWAY ORGANIZATION 4 A. Structure and Organization B. Committees, Representatives, Partners, Stakeholders C. Leaders’ Contact Information D. Level of Participation in State/Regional Meetings and Trainings E. Byway Leadership Succession Plan IV. BYWAY CORRIDOR CONDITIONS 5 A. Road Conditions and Signage B. Primary and Secondary Intrinsic Quality/Resources C. Changes in Intrinsic Quality/Resources since last CMP D. Accessibility to Intrinsic Quality/Resources V. VISITOR EXPERIENCE 10 A. Interpretation since Designation B. Byway Story C. Future Interpretation D. Plans for Improving Visitor Experience E. Preservation VI. MARKETING AND PROMOTION 13 A. Current and Future Planned Marketing Activities B. Recommended Products or Attachments for Media and Public Relations VII. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION 14 A. Ongoing Communication & Cooperation with Community Partners B. Public Meetings and Public Participation Opportunities C. Steps Taken to Update Byway Mission and Vision D. Narrative on Critical Issues and How They Will Be Addressed VIII. APPENDIX 15 A. Sign Inventory (Excel Spreadsheet of GIS data) B. Most Current Byway Map C. Maps Identifying Primary Intrinsic Quality/Resource Locations D. Seasonal Byway Photographs – 2 per season E. Marketing Materials I. INTRODUCTION AND MAP A. Byway Introduction Scioto County derives its name from a Native American word for “deer.” The Scioto and Ohio rivers meet in Scioto County, and the area’s hilly terrain, the foothills of the Appalachia Mountains, is often described as the “Little Smokies.” First settled in 1803, the county is rich in history, full of river lore and Native American influences, which is matched only by its natural beauty. -

Special Ohio Report

97 Years of Legislative Reporting in Ohio SPECIAL OHIO REPORT SPECIAL REPORT 123rd General Assembly Date Published: Friday, December 08, 2000 TERM LIMITS CREATE REPEAT OF 1972 ELECTION THAT BROUGHT 43 NEW MEMBERS TO GENERAL ASSEMBLY In early January of 1961, 136 members of the Ohio House of Representatives were sworn into office. One was Bob Netzley, a petroleum products dealer out of Laura in western Ohio’s Miami County. He arrived in Columbus with an agenda in hand that was chiseled out of the bedrock of Republican Party conservatism that has, like the man, endured through nearly forty years of social experimentation, from President Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” to - as it now stands - a President who either will show “compassionate conservatism” or one that will put some social programs in a “lock box.” Six years after Mr. Netzley arrived at the Statehouse, Troy Lee James decamped from one of Cleveland’s toughest neighborhoods to join Mr. Netzley in an Ohio House that, by 1967, had been reduced to 99 members as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court’s “one man, one vote” decision. Mr. James also had an agenda. It reflected not only traditional Democratic Party themes, but more subtle objectives that could only be achieved by personal conduct and - at times - tolerating personal humiliation. This month, Messrs. Netzley and James, the only two remaining state lawmakers from the tumultuous decade of the 1960s, will leave Columbus, having defeated all challenges through the years with the exception of term limits and the ravages that age can visit upon a body. -

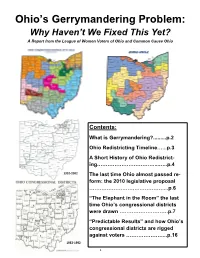

Ohio's Gerrymandering Problem

Ohio’s Gerrymandering Problem: Why Haven’t We Fixed This Yet? A Report from the League of Women Voters of Ohio and Common Cause Ohio Contents: What is Gerrymandering?.........p.2 Ohio Redistricting Timeline…...p.3 A Short History of Ohio Redistrict- ing……………………………...…..p.4 1992-2002 The last time Ohio almost passed re- form: the 2010 legislative proposal ……………………….……………...p.6 “The Elephant in the Room” the last time Ohio’s congressional districts were drawn ……………………….p.7 “Predictable Results” and how Ohio’s congressional districts are rigged against voters …………………...p.16 1982-1992 1 What is Gerrymandering? Redistricting 101: Why do we redraw districts? • Every ten years the US Census is conducted to measure population changes. • The US Supreme Court has said all legislative districts should have roughly the same population so that everyone’s vote counts equally. This is commonly referred to as “one person, one vote.” • In the year following the Census, districts are redrawn to account for people moving into or out of an area and adjusted so that districts again have equal population and, for US House districts, may change depending on the number of districts Ohio is entitled to have. • While the total number of state general assembly districts is fixed -- 99 Ohio House and 33 Ohio Senate districts -- the number of US House districts allocated to each state may change follow- ing the US Census depending on that state’s proportion of the total US population. For example, following the 2010 Census, Ohio lost two US House seats, going from 18 US House seats in 2002-2012 to 16 seats in 2012-2022. -

Master Plan 2008 Forward Shawnee State University Portsmouth, Ohio

Master Plan 2008 Forward Shawnee State University Portsmouth, Ohio September 2007 Revised January 2011 Prepared by Jim Butz, Ltd. Columbus, Ohio Master Plan 2008 Forward Shawnee State University TABLE OF CONTENTS UNIVERSITY BACKGROUND 1 History 1 Mission 1 Location 1 Academics 2 Student Enrollment Table 2 Cost 3 Students 3 Campus Life 4 Strategic Plan 5 PLANNING PROCESS 5 Acknowledgements 6 Exhibit – Aerial Photograph 7 EXISTING CONDITIONS 8 Boundaries and Land Use 8 Buildings 8 Existing Building Table 9 Campus Amenities 10 Utilities 10 Water Service 11 Exhibit – Water System 12 Sewer System 13 Exhibit – Storm, Sanitary & Combined Sewers 14 Storm Water Management 15 Natural Gas Distribution 16 Exhibit – Natural Gas 17 GOALS and OBJECTIVES 18 Goal No. 1 – Facilitate Growth 18 Goal No. 2 – Strengthen the University Community 19 Goal No. 3 – Foster Community Partnerships 20 Goal No. 4 – Provide Adequate Infrastructure 20 THE MASTER PLAN 22 Land Use and Neighborhoods 22 Exhibit – Land Use Diagram 23 Boundaries and Property Acquisition 24 TC1 Master Plan 2008 Forward Shawnee State University Master Plan 24 Exhibit – Property Acquisition 25 Exhibit – Master Plan 26 Exhibit – Plan Detail at Academic Core 27 Exhibit – Plan Detail at Campus Center 28 Exhibit – Plan Detail at Ball Fields 29 Exhibit – Plan Detail at North Residences 30 Exhibit – Plan Detail at Northeast Corner 31 BUILDING SITES 32 Building Area Table 34 Exhibit – Building Sites 35 CAMPUS AMENITIES 36 Exhibit – Campus Amenities 40 VEHICULAR CIRCULATION 41 Campus Access 41 Campus Entry Portals 42 Campus Roads and Drives 42 Emergency, Security and Service Access 43 Signage 43 Exhibit – Vehicular Circulation 45 VEHICULAR PARKING 46 Parking Inventory Table 47 Exhibit – Vehicular Parking 48 PEDESTRIAN CIRCULATION 49 Exhibit – Pedestrian Circulation 50 SERVICES and UTILITIES 51 Utility Corridors 51 Storm Water and Sanitary Sewerage 51 TC2 Master Plan 2008 Forward Shawnee State University UNIVERSITY BACKGROUND History Shawnee State University is Ohio’s newest and fastest growing public university. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing fi’om left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microlilms International A Beil & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.761-4700 800,521-0600 Order Number 9130556 The development of the Black Elected Democrats of Ohio (BEDO) into a viable state legislative caucus Simms-Maddox, Margaret J., Ph.D. -

Ryan Smith State Representative 133Rd General Assembly

Columbus Office 93rd House District Vern Riffe Center Representing 77 S. High Street Gallia, Jackson, 11th Floor Lawrence and Columbus, Ohio 43215 Vinton Counties (614) 466-1366 [email protected] Ryan Smith State Representative 133rd General Assembly February 27, 2019 Secretary Elaine L. Chao United State Department of Transportation 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20590 Dear Secretary Chao: I am writing to support the Ohio Department of Transportation’s application for the Infrastructure for Rebuilding America (INFRA) grant to fund the Appalachian Opportunity Corridor Project in southern Ohio. This application is being co-sponsored by the Clermont County Transportation Improvement District. The Appalachian Opportunity Corridor – also known as Corridor D of the Appalachian Development Highway System – includes portions of Ohio State Route 32 and US Route 50 and connects the Cincinnati metro region with Bridgeport, West Virginia, in the heart of Appalachia. Investment along this critical roadway would plant a seed of change for many underserved communities and would provide a meaningful combination of both economic and safety benefits to those who use this corridor, which is a principal arterial for the movement of people, goods and services throughout the state, and is one of the highest-volume local routes in Ohio. This project seeks to improve the quality of life for countless residents of southern Ohio through improved transportation routes that will in turn benefit the region’s healthcare, education, and economic development -

Your Information Your Rights Our Responsibilities Client Handbook

Client Handbook _________________________________________ Your Information Your Rights Our Responsibilities This handbook provides information about agency services, your rights and responsibilities, how protected health information may be used and disclosed and how you may access your health information. Please review it carefully. ______________________________________ February 2021 Contents Service Locations & Hours 2 Your Rights 4 Your Responsibilities 5 Explanation of Services 7 Ethical Standards 9 Notice of Privacy Practices 12 Grievance Policy & Procedures 14 Clermont County Mental Health & Recovery Board Notice of Privacy Practices 16 Service Locations & Hours 513.752.1555 Location Address Hours Child Focus, Inc. 4633 & 4629 Aicholtz Road M - TH 8:00 am - 9:00 pm Mt. Carmel, Ohio Cincinnati, Ohio 45244 F - 8:00 am - 4:30 pm (Clermont County) Ph# 513-752-1555 S - 8:00 am - 4:30pm (by appointment) Child Focus, Inc. 4286 Wuebold Lane Wasserman Day Treatment Center Cincinnati, Ohio 45245 M - F 8:00 am - 4:30 pm (Clermont County) Ph# 513-732-8800 Wasserman Day Treatment Center 1317 South Second Stree M - F 8:00 am - 4:30 pm (Brown County) Ripley, Ohio 45167 Ph# 937-392-4384 Child Focus, Inc. 988 Ohio Pike M - TH 8:00 am - 6:00 pm Amelia, Ohio Cincinnati, Ohio 45102 F - 8:00 am - 4:00 pm (Clermont County) Ph# 513-752-1555 Genesis 463 South Broadway Street M - F 7:00 am - 3:00 pm Williamsburg, Ohio Batavia, OH 45103 (Clermont County) Ph# 513-724-8555 Health Source 6535 Charles Snider Road By Appointment Loveland, Ohio Loveland, Ohio 45140 (Clermont County) Ph# 513-575-1444 Felicity Christian Church 847 State Route 133 By Appointment Felicity, Ohio Felicity, Ohio 45120 (Clermont County) Ph# 513-752-1555 Child Focus, Inc. -

TITLE Urban University Program, RR-92-02. INSTITUTION Ohio State Legislative Office of Education Oversight, Columbus

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 387 HE 029 063 TITLE Urban University Program, RR-92-02. INSTITUTION Ohio State Legislative Office of Education Oversight, Columbus. PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 63p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.)(120) Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Community Development; Higher Education; Metropolitan Areas; *Outreach Programs; Program Effectiveness; Program Evaluation; Social Responsibility; *State Programs; Technical Assistance; Urban Education; *Urban Universities IDENTIFIERS *Ohio ABSTRACT This report evaluates the Urban University Program (UUP), designed to improve urban outreach activities at eight Ohio Universities: Cleveland State University, Kent State University, Ohio State University, University of Akron, University of Cincinnati, University of Toledo, Wright State University, and Youngstown State University. The UUP provides craining and education, research, technical assistance, and data base services to Ohio's urban areas. Assessment involved interviews, observation of meetings, and program document review. Findings are reported in terms of the purpose, funding, organization, and impact of the program. The report concludes that the program has accomplished the general intent of addressing the needs of Ohio's urban centers in a positive manner. Suggested improvements in the program include better information on its impact on cities, a more equal distribution of funds among the eight schools, more priority to developing a state-level audience, more focus by UUP leadership on issues important to program success, and more coordination of local and regional efforts. Recommendations include development of statutory language to clarify the intent of UUP and development of an ongoing evaluation program. Appendixes provide the background questions used for analysis, a summary of UUP activities by school, a listing of research and technical assistance grants, and recommendations by and responses to the review panel. -

Legislative Platform Biennial Report

Judicial Conference Ohio Judicial Conference Legislative Platform 2019-2020 Biennial Report & 2017-2018 A Word from the Ohio Judicial Conference January 2019 The Honorable Mike DeWine, Governor The Honorable Larry Obhof, President Vern Riffe Building, 30th Floor The Ohio Senate 77 South High Street 1 Capitol Square, Room 201 Columbus, OH 43215 Columbus, Ohio 43215 The Honorable Kenny Yuko, Minority Leader The Honorable Larry Householder, Speaker The Ohio Senate The Ohio House of Representatives 1 Capitol Square, Room 303 Vern Riffe Building, 14th Floor Columbus, Ohio 43215 77 South High Street Columbus, Ohio 4321 The Honorable Emilia Sykes, Minority Leader Mark Flanders, Director The Ohio House of Representatives Legislative Service Commission 77 South High Street, 14th Floor 77 South High Street, 9th Floor Columbus, Ohio 43215 Columbus, Ohio 43215 Enclosed is the 2019-2020 Legislative Platform and 2017-2018 Biennial Report of the Ohio Judicial Conference. We hope that you will consider the issues presented in the 2019-2020 Platform and contact us if you are interested in working together on one or more of them. Of course, we also stand ready to provide you with independent information or comment on any issues of interest to you that might impact Ohio’s courts or the judiciary. As a record of proceedings of the Conference for the past two years and a plan for the next two years, these materials constitute our statutory obligation to report and make recommendations for the improvement of the administration of justice. In addition to the legislative work of the Conference, the OJC was called on last year to take a position on a Constitutional amendment, something that is rarely done but something that was necessary in 2018 because of State Issue 1’s enormous impact on the administration of justice. -

Scioto County Board of DD Guthrie Now Director of School Programs Tammy Guthrie Has Been «I Take Pride in in Elementary Educati On

May 2016 Together, We Build Meaningful Lives Scioto County Board of DD Guthrie now Director of School Programs Tammy Guthrie has been «I take pride in in Elementary Educati on. She earned named Director of School Pro- her master’s degree in Interventi on grams at Scioto County Board the opportunity from University of Rio Grande and is of Developmental Disabiliti es. provided to me completi ng a Ph.D. in Special Educati on This positi on is equivalent to and look forward Administrati on at Capella University. principal and directly super- Prior to being hired in 2015 as Ear- vises staff and operati ons at to going to work ly Educati on Supervisor at SCBDD, Vern Riff e School. every day.» Guthrie worked as a teacher in the She has been Interim Direc- Tammy Guthrie Portsmouth City Schools. tor of School Programs since “Since taking the helm in January, Mark Cornwell’s reti rement was happy that the students remem- Tammy has proven herself to be an earlier this year. bered me after all these years. I take excellent leader who is highly qualifi ed “It is an honor to work in this ca- pride in the opportunity provided to in the arena of educati on and inter- pacity with our students, families, and me and look forward to going to work venti on services,” said Superintendent staff ,” Guthrie said. “I taught several every day.” Julie Monroe. “She’s an asset to our of our high school-aged students in Guthrie is a nati ve of West Ports- organizati on, and the Board and I elementary school and remained close mouth and a graduate of the University are very pleased to have her in the with their families over the years. -

“New Deal Republican:”

“NEW DEAL REPUBLICAN:” JAMES A. RHODES AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE REPUBLICAN PARTY, 1933-1983 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By William Russell Coil, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Warren Van Tine, Adviser Professor David Stebenne __________________________ Professor Andrew Cayton Adviser Graduate Program in History Copyright by William Russell Coil 2005 ABSTRACT Ohio governor James Allen Rhodes (1909-2001) lived both an authentic American success story and an embellished populist myth. The son of a coal miner, Rhodes survived the insecurity that characterized the lives of early twentieth-century working-class Americans, matured after an extended adolescent aimlessness, and became Ohio's most powerful governor. He also exaggerated key parts of his biography and omitted other events in order to authenticate his credentials as a champion of the common man. From this odd mix of fact and fiction emerges a story of an important but overlooked politician. This dissertation is the first full length investigation into Rhodes’ life and political career, placing him in a larger context of regional political change, the rise of the consumer culture, and the working-class origins of populist economic security. Before Rhodes, Midwestern Republicans opposed the New Deal and saw nothing more than slavery in Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s promise to deliver economic security to American voters. As Ohio’s longest serving governor (1963-1971 and 1975-1983), as a child of the insecure working class, and as a young politician maturing in the 1930s, Rhodes made security the central part of his Republican philosophy.