Imagereal Capture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inaugural Speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith

Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to thank officers from both Houses for their comments on a draft of this paper, in particular Stephanie Hesford and Jonathan Elliott from the Legislative Assembly and Stephen Frappell and Samuel Griffith from the Legislative Council. Thanks, too, to Lenny Roth and Greig Tillotson for their comments and advice. Any errors are the author’s responsibility. ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978 0 7313 1900 8 May 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament by Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Acting Senior Research Officer, Law ............................................ (02) 9230 3085 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. -

The French Economic Mission to Australia 1918

JACQUELINE DWYER 30 AHEAD OF THEIR TIME: THE FRENCH ECONOMIC MISSION TO AUSTRALIA 1918 JACQUELINE DWYER Introduction In the closing weeks of the Great War, Sydney was taken over by the enthusiastic welcome given to the delegates of an Economic Mission to Australia, sent on behalf of the government of France. They had that morning disembarked from the steamship Sonoma after their journey across the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco.1 The Mission’s principal aim was to re-establish and enhance the trading conditions that had existed between France and Australia in the years preceding the war, taking advantage of Germany’s eclipse. The French Department of Foreign Affairs hoped also to discuss the destiny of former German colonies in the South Pacific, and to resolve the pending situation of the New Hebrides.2 These delegates were to spend three months in Australia, visiting the other state capitals and regional centres where similar welcomes awaited them, and where they were shown the potential trading resources of this nation. This article proposes, through a more detailed description and analysis of the Mission than has been done to date, to cast light on French-Australian relations of the time, combining a number of sources. The Mission’s official report for the general public, The Economic Relations between France and Australia, published in English in 1919, is a detailed assessment of their bilateral trade.3 Especially valuable was Robert Aldrich’s article (1989), ‘La Mission Française en Australie de 1918’, based on the diplomatic archives of the Quai d’Orsay. (Its title has been shortened to Confidential Report.) A third report is the Rapport Thomsen. -

T'the Phoenix Has Now Risen from Its Ashes

THE ACADEMY & THE HUMANITIES IN 19691 » Graeme DAVison ‘The Phoenix has now risen from its ashes, Seventy-one year old Hancock and a lovelier bird and — what matters more — a seventy-five year old Menzies were near- Tlivelier one’, the inaugural president of the contemporaries, having both arrived at the Australian Academy of the Humanities, Sir University of Melbourne as scholarship boys Keith Hancock, wrote exultantly to its political in the years around World War One. Each patron, Sir Robert Menzies, at the end of man, in his way, had been imbued with ideals September 1969. ‘We have not only a new name of academic and public service through their but a new infusion of creative vigour’.2 Since studies under the university’s influential the foundation of the Australian Humanities Professor of Law, Harrison Moore.3 Both were Research Council (AHRC) in 1955, its founders products of the liberal imperialism of their era, had anticipated its transformation, in due Hancock becoming the pre-eminent historian course, into an Academy of Letters or, as it of the British Empire, and Menzies one of 'THE PHOENIX HAS NOW RISEN FROM ITS ASHES, A LOVELIER BIRD AND — WHat MattERS MORe — A LIVELIER ONE' — sIR KEITH HANCOCK IN A LEttER TO SIR ROBERT MENZIES, 1969. turned out, an Academy of the Humanities. its most devoted political servants. While The plumage of the new bird, with its royal Hancock had won academic laurels in Oxford charter and crest, was certainly more glorious and London, returning to his homeland only than that of the old AHRC, but the bird itself towards the end of his career, Menzies had was remarkably like the old one. -

PART THREE Chapter Five Hope

PART THREE Chapter Five Hope For many former members of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) after World War I, life on the land on a small poultry or vegetable block in company with other returned men represented more than just a return to civilian life. It was hope – hope that the horrors of war could be erased, hope that the emerging new world would be more prosperous, and hope that their lives would be re-built through their own enterprise of land ownership. For a considerable number of men on these group settlements it was also their last hope. Expectations of success were, therefore, high in the beginning on these settlements. The previous chapters of this thesis have outlined the settlements’ origins and establishment and some of the issues facing settlers, such as poor quality land, stock or crops. These difficulties made earning a living from small acreages more arduous than the men had been led to believe and they often soon found themselves with little income and a massive debt. In addition to the problems of flooding and inferior land, badly constructed homes, poor communication systems, and isolation for themselves and their families, most of the men had war-related disabilities to contend with. In spite of all these challenges, these soldier settlers attempted to re-adapt to civilian life and to build a sustainable community as part of a group soldier settlement. To support the argument of this thesis that most soldier settlers on the six group settlements in this study returned from World War I service physically and mentally 180 scarred, leaving them with long-term or permanent disabilities, a number of primary sources have been used to build a picture of how they struggled to make a living after the war. -

Papers of Sir Edmund Barton Ms51

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA PAPERS OF SIR EDMUND BARTON MS51 Manuscript Collection 1968-70, 1996 and last amended 2001 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview 3 Biographical Note 6 Related Material 8 Microfilms 9 Series Description 10 Series 1: Correspondence 1827-1921 10 Series 2: Diaries, 1869, 1902-03 39 Series 3: Personal documents 1828-1939, 1844 39 Series 4: Commissions, patents 1891-1903 40 Series 5: Speeches, articles 1898-1901 40 Series 6: Papers relating to the Federation Campaign 1890-1901 41 Series 7: Other political papers 1892-1911 43 Series 8: Notes, extracts 1835-1903 44 Series 9: Newspaper cuttings 1894-1917 45 Series 10: Programs, menus, pamphlets 1883-1910 45 Series 11: High Court of Australia 1903-1905 46 Series 12: Photographs (now in Pictorial Section) 46 Series 13: Objects 47 Name Index of Correspondence 48 Box List 61 2 PAPERS OF EDMUND BARTON MS51 Overview This is a Guide to the Papers of Sir Edmund Barton held in the Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Australia. As well as using this guide to browse the content of the collection, you will also find links to online copies of collection items. Scope and Content The collection consists of correspondence, personal papers, press cuttings, photographs and papers relating to the Federation campaign and the first Parliament of the Commonwealth. Correspondence 1827-1896 relates mainly to the business and family affairs of William Barton, and to Edmund's early legal and political work. Correspondence 1898-1905 concerns the Federation campaign, the London conference 1900 and Barton's Prime Ministership, 1901-1903. -

Professor Carolyn Evans, Vice Chancellor and President, Griffith

Professor Carolyn Evans, Vice Chancellor and President, Griffith University Professor Carolyn Evans commenced her appointment as Vice Chancellor and President of Griffith University in February 2019, leading one of Australia’s fastest-growing and most progressive tertiary institutions, ranked in the top 2% of universities worldwide. Prior to joining Griffith, Professor Evans was Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Graduate and International) and Deputy Provost (2017-2018) at the University of Melbourne, and Dean and Harrison Moore Professor of Law, University of Melbourne Law School (2011-2017). Professor Evans has degrees in Arts and Law from the University of Melbourne and a doctorate from Oxford University, where she studied as a Rhodes Scholar and held a stipendiary lectureship for two years. In 2010, Carolyn was awarded a Fulbright Senior Scholarship to allow her to travel as a Visiting Fellow to American and Emory Universities to examine questions of comparative religious freedom. She has also taught in the human rights summer school at European University Institute. Throughout her career, Carolyn has promoted the importance of universities combining excellence in teaching and research with a commitment to social justice and inclusion. Carolyn is the author of Legal Protection of Religious Freedom in Australia (Federation Press 2012), Religious Freedom under the European Court of Human Rights (OUP 2001) and co-author of Australian Bills of Rights: The Law of the Victorian Charter and the ACT Human Rights Act (LexisNexis 2008). She is co-editor of Religion and International Law (1999, Kluwer); Mixed Blessings: Laws, Religions and Women's Rights in the Asia-Pacific Region (2006 Martinus Nijhoff) and Law and Religion in Historical and Theoretical Perspective (CUP 2008). -

LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154-56, M1584 Rt. Hon. Marquess of Linlithgow Hopetoun House South Queensferry Lothian Scotland EH30 9SL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1973, 1980, 1983 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE John Adrian Louis Hope (1860-1908), 7th Earl of Hopetoun (succeeded 1873), 1st Marquess of Linlithgow (created 1902), was born at Hopetoun House, near Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but did not enter the Army. In 1883 he was appointed Conservative whip in the House of Lords and in 1885 was made a lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria. In 1886 he married Hersey Moleyns, the daughter of Lord Ventry. In 1889 Lord Knutsford, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, appointed Hopetoun as Governor of Victoria and he held the post until March 1895. Although it was a time of economic depression, he entertained extravagantly, but his youthful enthusiasm and fondness for horseback tours of country districts won him considerable popularity. His term coincided with the first federation conferences and he supported the federation movement strongly. In 1895-98 Hopetoun was paymaster-general in the government of Lord Salisbury. In 1898 Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, offered him the post of Governor-General of Canada, but he declined. He was appointed Lord Chamberlain in 1898 and had a close association with members of the Royal Family. In July 1900 Hopetoun was appointed the first Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. He arrived in Sydney on 15 December 1900 and his first task was to appoint the head of the new Commonwealth ministry. -

The Australian Dried Fruits Association, Controlling Purchasing, Packing and Marketing

A New Idea Each Morning How food and agriculture came together in one international organisation Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Way, Wendy. Title: A new idea each morning : how food and agriculture came together in one international organisation / Wendy Way. ISBN: 9781922144102 (pbk.) 9781922144119 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: International organization. Intellectual cooperation. Food-supply--International cooperation. Agriculture--International cooperation. Dewey Number: 327.17 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Illustration . vii Preface and Acknowledgments . xi List of Figures . xv List of Tables . xvii Imperial Currency and Weights . xix Abbreviations . xxi Introduction . 1 Part A: Visions of Empire Prologue . 7 1 . Renmark . 15 2 . Working with Bruce . 37 3 . A Vision of Empire . 61 4 . The Vision Ends . 93 Part B: The League of Nations Prologue . 123 5 . The Wheat Crisis of the 1930s . 129 6 . ‘The Marriage of Health and Agriculture’ . 153 7 . A Vision for the League of Nations . 175 Part C: A New Deal for the World Prologue . 211 8 . The War of Ideas . 217 9 . ‘A Keen Outsider’ . 243 10 . -

SIR DUDLEY DE CHAIR Memoirs , C. 1955

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SIR DUDLEY DE CHAIR Memoirs , c. 1955 Reel M716 Commander H.G.D. de Chair Maintop Felden Lane Boxmoor, Hertfordshire National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1969 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Sir Dudley Rawson Stratford de Chair (1864-1958) was born in Lennoxville, Canada. His uncle, Admiral Sir Harry Rawson, was Governor of New South Wales in 1902-9. De Chair’s family returned to England in 1870 and in 1878 he joined the Royal Navy, becoming a midshipman in 1880. He was promoted to commander in 1897, captain in 1902 and rear admiral in 1912. De Chair married Enid Struben in 1903. In 1915-16 he was commander of the tenth cruiser squadron, which was responsible for the North Sea blockade of Germany. He was knighted in 1916 and promoted to vice admiral in 1917. In 1918 he took command of the coastguard and reserves. He became an admiral in 1920. De Chair was appointed Governor of New South Wales in October 1923 and he and Lady de Chair arrived in Sydney in February 1924. He faced considerable political difficulties following the election in May 1825 of a Labor Government led by J.T. Lang. Lang’s attempts to appoint 25 new members to the Legislative Council, with the ultimate aim of abolishing the Council, were foiled by de Chair, leading to calls from Government supporters for his recall. The tensions between Premier and Governor ended when the Lang Government was defeated at the election in October 1927. The rest of the governorship was mostly uneventful. -

FEDERALISM : a CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS Author(S): S

Indian Political Science Association FEDERALISM : A CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS Author(s): S. A. Paleker Source: The Indian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 67, No. 2 (APR.- JUNE, 2006), pp. 303- 310 Published by: Indian Political Science Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41856217 Accessed: 02-04-2020 06:17 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indian Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Indian Journal of Political Science This content downloaded from 182.68.63.46 on Thu, 02 Apr 2020 06:17:42 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Indian Journal of Political Science Vol. LXVII, No. 2, Apr.-June, 2006 FEDERALISM : A CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS S. A. Paleker Most of the studies on federalism centre around the legislative, financial and administrative relations between the Centre and the States. Very little attention has been paid to the theory- building. In this paper an attempt has been made to deal with certain theories of federalism today. The paper deals with a conceptual analysis of federalism. Here a review of classical theory, origin theory and functional theory has been made but the conclusion is that each theory of federalism contains elements of validity and usefulness though each of the theories also suffers from inadequacies. -

The People and the Constitution

THE PEOPLE AND THE CONSTITUTION THE HON JUSTICE PATRICK KEANE AC* It is a great honour to have been asked to give this year’s Lucinda Lecture. It would be churlish of me, as a Queenslander, to observe that at the time that the great work was done on the ship after which this lecture is named, she was owned and crewed by Queenslanders. It would be churlish, but we Queenslanders acknowledge no equals when it comes to our capacity for churlishness. However, quite apart from being churlish, it would be wrong on this occasion to make special claims for the contributions of particular colonies because the work which was done on the Lucinda was done by individuals who made themselves the first Australians. By their efforts, they ensured that we, too, would have that privilege. Their work stands as an enduring reminder that, just as those individuals from their separate colonies combined their talents to forge a nation, so today’s Australians can work together to make a more just nation with confidence that their efforts will not be in vain. I THE PEOPLE IN POLITICS It was only in the latter half of the 18th century that the idea of the people as a source of sovereign authority emerged as a central element of political discourse in the west. And once it emerged it almost immediately became the focus of fierce polemic. Edmund Burke, in his reaction to the French Revolution, spoke of the aristocracy and higher clergy, and those who deferred to them, as the only true ‘people’ of France. -

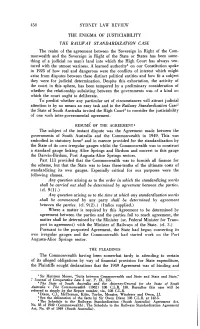

THE RAILWAY STANDARDIZATION CASE Any Question

SYDNEY LAW- REVIEW THE ENIGMA OF JUSTICIABILITY THE RAILWAY STANDARDIZATION CASE The realm of the agreement between the Sovereign in Right of the Com- monwealth and the Sovereign in Right of the State or States has been some- thing of a judicial no man's land into which the High Court has always ven- tured with the utmost wariness. A learned authority1 on our Constitution spoke in 1925 of how real and dangerous were the conflicts of interest which might arise from disputes between these distinct political entities and how fit a subject they were for judicial determination. Despite this exhortation, the activity of the court in this sphere, has been tempered by a preliminary consideration of whether the relationship subsisting between the governments was of a kind on which the court ought to deliberate. To predict whether any particular set of circumstances will attract judicial attention is by no means an easy task and in the Railway Standardization Case' the State of South Australia invited the High Court3 to consider the justiciability of one such inter-governmental agreement. RESUME/ OF THE AGREEMENT4 The subject of the instant dispute was the Agreement made between the governments of South Australia and the Commonwealth in 1949. Th'is was embodied in statutory form5 and in essence provided for the standardization by the State of its own irregular gauges whilst the Commonwealth was to construct a standard gauge linking Alice Springs and Birdum and convert to this gauge the Darwin-Birdum, Port Augusta-Alice Springs sectors. Part 111 provided that the Commonwealth was to furnish all finance for the scheme, but that the State was to bear three-tenths of the ultimate costs of standardizing its own gauges.