Slum-Fit? Or, Where Is the Place of the Filipinx Urban Poor in the Philippine City?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY National Ecology Center, East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Phone Nos

LAGUNA LAKE DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY National Ecology Center, East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Phone Nos. (02) 8 376-4039, (02) 8 376-4072, (02) 8 376-4044, (02) 8 332-2353, (02) 8 332-2341, (02) 8 376-5430 Locals 115, 116, 117 and look for Ms. Julie Ann G. Blanquisco or Ms. Marivic A. Dela Torre-Santos E-mail: [email protected] | [email protected] Website: http://llda.gov.ph List of APPROVED DISCHARGE PERMITS as of September 03, 2021 Establishment Address Permit No. Approve Date 11 FTC Enterprises, Inc. 236 P. Dela Cruz San Bartolome Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03532 August 18, 2021 189 Realty Corp. (CI Market) Qurino Highway Santa Monica, Novaliches Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03744 August 20, 2021 189 Realty Corporation - 2nd (CI Market/Commercial Complex) Quirino Highway, Sta. Monica Novaliches Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03743 August 20, 2021 21st Century Mouldings Corporation 18 F. Carlos St. cor. Howmart Road Apolonio Samson Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03541 August 23, 2021 24K Property Ventures, Inc. (20 Lansbergh Place Condominium) 170 T. Morato Ave. cor. Sct. Castor Sacred Heart Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-02819 July 15, 2021 3J Foods Corp. Sta. Ana San Pablo City Laguna DP-16d-2021-03174 August 06, 2021 8 Gilmore Place Condominium 8 Gilmore Ave. cor. 1st St. Valencia New Manila Quezon City MM DP-25b-2021-03829 August 27, 2021 AC Technical Services, Inc. 5 RMT Ind`l. Complex Tunasan Muntinlupa City MM DP-23a-2021-01804 May 12, 2021 Ace Roller Manufacturing, Inc. -

Company Name: Ayala Land Malls Inc. Corporate Address: 5Th Floor, Glorietta 4, Ayala Center Makati City

Company Name: Ayala Land Malls Inc. Corporate Address: 5th Floor, Glorietta 4, Ayala Center Makati City Mall List Luzon Mall Name Mall Location Harbor Point Subic Bay Freeport Zone, Zambales MarQuee Mall Angeles City, Pamapanga Ayala Malls Cloverleaf A Bonifacio Ave Brgy Balingasa, Quezon City TriNoma Edsa Corner North Avenue, Quezon City Ayala Malls Vertis North North Avenue Brgy Bagong Pag-asa, Quezon City Fairview Terraces Quirino Highway cor Maligaya Drive Novaliches, Quezon City U.P. Town Center Katipunan Avenue Diliman, Quezon City Ayala Malls Feliz Amang Rodriguez Cor J.P. Rizal Brgy Dela Paz, Pasig City Ayala Malls Marikina Liwasag Kalayaan Brgy Marikina Heights, Marikina City Ayala Malls The 30th Meralco Ave. Brgy Ugong, Pasig City Market! Market! Bonifacio Global City, Taguig One Ayala Ave Ayala Avenue, Makati City Glorietta Ayala Center, Makati City Greenbelt Legazpi Street, Makati City Ayala Malls Circuit Circuit Makati, Hippodromo, Carmona, Makati City Ayala Malls Manila Bay Macapagal Blvd cor. Aseana Avenue, Paranaque City Alabang Town Center Alabang Town Center, Muntinlupa City The District Dasma Molina Road, Dasmarinas, Cavite The District Imus Aguinaldo Highway cor. Daang Hari Road Anabu II-D, Imus, Cavite Vermosa Daang Hari Road cor. Vermosa Blvd., Imus, Cavite Ayala Malls Solenad Nuvali, Brgy. Sto. Domingo, City of Santa Rosa, Laguna Ayala Malls Serin Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo Highway Tagaytay City, Cavite Ayala Malls Legazpi Rizal Street corner Quezon Ave., Barangay Capantawan, Legazpi City, Albay Mall List VisMin Mall Name Mall Location Abreeza J.P. Laurel Ave., Davao City Ayala Center Cebu Cebu Business Park, Cebu City Central Bloc I. Villa Street Cebu IT Park, Cebu City Centrio Mall CM Recto-Corrales Ave, Cagayan de Oro Ayala Malls Capitol Central Gatuslao Street, Bacolod City . -

Clement Castigador Camposano, Ph.D

UPD_EDUC_EDFD_CV_CCamposano Clement Castigador Camposano, Ph.D. Profile Clem Camposano earned his Ph D. in Philippine Studies (Anthropology) from the Tri-College Program of the University of the Philippines - Diliman in 2009. He holds an M.A. in Political Science from U.P Diliman (1992) and a B.A. in Political Science and History (double major) from U.P. Visayas (1986). His current research interest is in the anthropology of contemporary migration, anthropology of education, Philippine history and culture, as well as citizenship and civic education. He has published articles in scholarly and peer-reviewed journals and has consistently presented academic papers in both local and international conferences. He is the current President of the Philippine Studies Association (PSA) and served in the board of the Anthropological Association of the Philippines/Ugnayang Pang-Aghamtao (UGAT) until 2016. As a practicing ethnographer, he actively works with the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC) in providing trainings in qualitative research methods to the academic staff of various educational institutions. He also sits in the Editorial Advisory Board of Filipinas: Journal of the Philippine Studies Association, Inc. Dr. Camposano has had a long academic career, serving various institutions in different capacities. He is presently a faculty member at the Division of Curriculum and Instruction – Educational Foundations, College of Education, University of the Philippines Diliman where he teaches courses in the anthropology and sociology of education. Prior to joining U.P. Diliman in 2017, he was a faculty member at the University of Asia and the Pacific (UA&P) where he taught courses in Philippine history and culture, Southeast Asian history, social science research, political theory and political dynamics. -

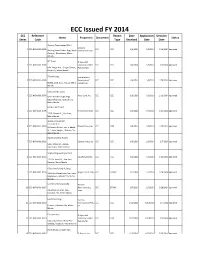

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date

ECC Issued FY 2014 ECC Reference Report Date Application Decision Name Proponent Document Status Series Code Type Received Date Date Alabang Town Center BPO 1 Alabang 1 ECC-NCR-1401-0001 ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Alabang Town Center, Brgy. Ayala, Commercial Corp. Alabang,, Muntinlupa, Metro Manila IBP Tower Ortigas and 2 ECC-NCR-1401-0003 Company Limited ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/6/2014 Approved Julia Vargas Ave., Ortigas Center,, Partnershipp Pasig City, Metro Manila T-Park Project Fort Bonifacio 3 ECC-NCR-1401-0005 Development ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/28/2014 Approved B18,L4, 26th, BGC,, Taguig, Metro Corporation Manila Vertis North Towers 4 ECC-NCR-1401-0006 Ayala Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/16/2014 Approved Vertis North Triangle, Brgy. Bagong Pag-asa,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Fortune Hill Project 5 ECC-NCR-1401-0008 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 173 P. Gomez St.,, San Juan, Metro Manila Studio A Residential Condominium 6 ECC-NCR-1401-0009 Filinvest Land, Inc. ECC IEER 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 1/20/2014 Approved 99 Xavierville Ave., cor. E. Abada St., Loyola Heights,, Quezon City, Metro Manila Plastic Recycling Project 7 ECC-NCR-1401-0011 Sanplas Industries ECC IEEC 1/6/2014 1/6/2014 2/7/2014 Approved 6390 Tatalon St., Ugong,, Valenzuela, Metro Manila Shipbuilding and Repair Yard 8 ECC-NCR-1401-0013 Sas Shipyard, Inc. -

REAL.ESTATE Cpdprogram.Pdf

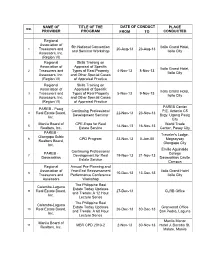

NAME OF TITLE OF THE DATE OF CONDUCT PLACE NO. PROVIDER PROGRAM FROM TO CONDUCTED Regional Association of 5th National Convention Iloilo Grand Hotel, 1 Treasurers and 20-Aug-13 23-Aug-13 and Seminar Workshop Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. (Region VI) Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 2 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 4-Nov-13 8-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 3 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 5-Nov-13 9-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice PAREB Center PAREB - Pasig Continuing Professional P.E. Antonio C5 4 Real Estate Board, 22-Nov-13 23-Nov-13 Development Seminar Brgy. Ugong Pasig Inc. City Manila Board of CPE-Expo for Real World Trade 5 14-Nov-13 16-Nov-13 Realtors, Inc. Estate Service Center, Pasay City PAREB - Traveler's Lodge, Olongapo Subic 6 CPD Program 23-Nov-13 0-Jan-00 Magsaysay Realtors Board, Olongapo City Inc. Emilio Aguinaldo Continuing Professional PAREB - College 7 Development for Real 19-Nov-13 21-Nov-13 Dasmariñas Dasmariñas Cavite Estate Service Campus Regional Annual Pre-Planning and Association of Year-End Reassessment Iloilo Grand Hotel 8 10-Dec-13 13-Dec-13 Treasurers and Performance Conference Iloilo City Assessors Workshop The Philippine Real Calamba-Laguna Estate Today Updates 9 Real Estate Board, 27-Dec-13 CLRB Office and Trends: A 12 Hour Inc. -

Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS

Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS PHYSICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE I. PHYSICAL PROFILE Geographic Location Barangay Lubas is located on the southern part of the municipality of La Trinidad. It is bounded on the north by Barangay Tawang and Shilan, to the south by Barangay Ambiong and Balili, to the east by Barangay Shilan, Beckel and Ambiong and to the west by Barangay Tawang and Balili. With the rest of the municipality of La Trinidad, it lies at 16°46’ north latitude and 120° 59 east longitudes. Cordillera Administrative Region MANKAYAN Apayao BAKUN BUGUIAS KIBUNGAN LA TRINIDAD Abra Kalinga KAPANGAN KABAYAN ATOK TUBLAY Mt. Province BOKOD Ifugao BAGUIO CITY Benguet ITOGON TUBA Philippines Benguet Province 1 Sally Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS POLITICAL MAP OF BARANGAY LUBAS Not to Scale 2 Sally Republic of the Philippines Province of Benguet Municipality of La Trinidad BARANGAY LUBAS Barangay Tawang Barangay Shilan Barangay Beckel Barangay Balili Barangay Ambiong Prepared by: MPDO La Trinidad under CBMS project, 2013 Land Area The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Cadastral survey reveals that the land area of Lubas is 240.5940 hectares. It is the 5th to the smallest barangays in the municipality occupying three percent (3%) of the total land area of La Trinidad. Political Subdivisions The barangay is composed of six sitios namely Rocky Side 1, Rocky Side 2, Inselbeg, Lubas Proper, Pipingew and Guitley. Guitley is the farthest and the highest part of Lubas, connected with the boundaries of Beckel and Ambiong. -

PHILIPPINE L STITUTE for DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Working Paper 83-01

PHILIPPINE L_STITUTE FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Working Paper 83-01 STUDIFS ON THE WOOD BASED FURNITURE, LEATHER PRODUGTS A_D FOOTWEAR MANUFACTURING INDUBTRIES Ok THE PHILIPPINES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to express our sincerest appreciation and gratitude for the cooperation, assistance and enaouragement of the following, with- out whom these studies would not have been completed: o Dr. Filologo Pante, Jr., Dr. Romeo Bautista, Mr. Isaac Puno III and Mr. Mario Ferramil of the Philippine Institute for Develop- ment Studies ; o Dr. Magdaleno Albarracin, Jr. and Prof. Remedios Balbin of the U.P. Business Research Foundation, Inc. o The SGV Foundation, Inc. and the SGV Development Center; o Messrs. Jaime Cari_o and Jose Cabacaa of Premiere Financing. C_P,; o Prof. Romeo dela Paz and Dr. Epictetus Patalin_hug of the U.Po College of Business Administration_ o Messrs. Edgardo Reyes and A1 de Lange, Jr. of the Chamber of Furniture Industries of the Philippines; o Mayor Osmundo de Guzman and Mr. Domingo Antonio of the Marikina Shoe Trade Commission; o Atty. Manuel Cruz of the Tanners Association of the Philippines; o Atty. Cora JacOb of £he leather products manufacturing industry; o Messrs. Gregorio Timbol and Juvenal CatejQy of the wood-based furniture industry; o Prof. Honesto Nuqui of the U.P. Computer Center; o Mr. Cristopher Gomez, for statistical advice, and Mr. Roberto Magno, Mr. Saturnino Navarrete and_, Ps_el_- Verdejo, for _omputer programming; and - ii - o Our research assistants, Ms. Araceli Paraiso, Mr. Ernesto Dacmnay, Ms. Gina Villa and Ms. Ma. Victoria Taro, and the corps of interviewers who helped us put together our data. -

Urban Fragmentation and Class Contention in Metro Manila

Urban Fragmentation and Class Contention in Metro Manila by Marco Z. Garrido A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jeffery M. Paige, Chair Dean Filomeno V. Aguilar, Jr., Ateneo de Manila University Associate Professor Allen D. Hicken Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Frederick F. Wherry, Columbia University Associate Professor Gavin M. Shatkin, Northeastern University © Marco Z. Garrido 2013 To MMATCG ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my informants in the slums and gated subdivisions of Metro Manila for taking the time to tell me about their lives. I have written this dissertation in honor of their experiences. They may disagree with my analysis, but I pray they accept the fidelity of my descriptions. I thank my committee—Jeff Paige, Howard Kimeldorf, Gavin Shatkin, Fred Wherry, Jun Aguilar, and Allen Hicken—for their help in navigating the dark woods of my dissertation. They served as guiding lights throughout. In gratitude, I vow to emulate their dedication to me with respect to my own students. I thank Nene, the Cayton family, and Tito Jun Santillana for their help with my fieldwork; Cynch Bautista for rounding up an academic audience to suffer through a presentation of my early ideas, Michael Pinches for his valuable comments on my prospectus, and Jing Karaos for allowing me to affiliate with the Institute on Church and Social Issues. I am in their debt. Thanks too to Austin Kozlowski, Sahana Rajan, and the Spatial and Numeric Data Library at the University of Michigan for helping me make my maps. -

Company Registration and Monitoring Department

Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance Securities and Exchange Commission SEC Building, EDSA, Greenhills, Mandaluyong City Company Registration and Monitoring Department LIST OF CORPORATIONS WITH APPROVED PETITIONS TO SET ASIDE THEIR ORDER OF REVOCATION SEC REG. HANDLING NAME OF CORPORATION DATE APPROVED NUMBER OFFICE/ DEPT. A199809227 1128 FOUNDATION, INC. 1/27/2006 CRMD A199801425 1128 HOLDING CORPORATION 2/17/2006 CRMD 3991 144. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL INC. 2/27/2009 CRMD 12664 18 KARAT, INC. 11/24/2005 CRMD A199906009 1949 REALTY CORPORATION 3/30/2011 CRMD 153981 1ST AM REALTY AND DEVLOPMENT CORPORATION 5/27/2014 CRMD 98097 20th Century Realty Devt. Corp. 3/11/2008 OGC A199608449 21st CENTURY ENTERTAINMENT, INC. 4/30/2004 CRMD 178184 22ND CENTURY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 7/5/2011 CRMD 141495 3-J DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION 2/3/2014 CRMD A200205913 3-J PLASTICWORLD & DEVELOPMENT CORP. 3/13/2014 CRMD 143119 3-WAY CARGO TRANSPORT INC. 3/18/2005 CRMD 121057 4BS-LATERAL IRRIGATORS ASSN. INC. 11/26/2004 CRMD 6TH MILITARY DISTRICT WORLD WAR II VETERANS ENO9300191 8/16/2004 CRMD (PANAY) ASSOCIATION, INC. 106859 7-R REALTY INC. 12/12/2005 CRMD A199601742 8-A FOOD INDUSTRY CORP. 9/23/2005 CRMD 40082 A & A REALTY DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES, INC. 5/31/2005 CRMD 64877 A & S INVESTMENT CORPORATION 3/7/2014 CRMD A FOUNDATION FOR GROWTH, ORGANIZATIONAL 122511 9/30/2009 CRMD UPLIFTMENT OF PEOPLE, INC. (GROUP) GN95000117 A HOUSE OF PRAYER FOR ALL NATIONS, INC. CRMD AS095002507 A&M DAWN CORPORATION 1/19/2010 CRMD A. RANILE SONS REALTY DEVELOPMENT 10/19/2010 CRMD A.A. -

Municipal Strategies to Address Homelessness In

municipal strategies to address homelessness in british columbia knowledge dissemination and exchange activities on homelessness homelessness knowledge development program municipal strategies to address homelessness in british columbia i municipal strategies to address homelessness in british columbia knowledge dissemination and exchange activities on homelessness homelessness knowledge development program Authors: Robyn Newton, Senior Researcher Design & Layout: Joanne Cheung © September 2009 SPARC BC is a charitable organization operating in BC since 1966. We work with communities and organizations on issues of accessibility, income security, community development, and social planning. We are a well known resource for evidence-based social research and provider of the Parking Permit Program for People with Disabilities. Access Awareness Day is an annual campaign to promote understanding and action around the need for a more inclusive and accessible society. social planning and research council of british columbia 4445 Norfolk Street, Burnaby BC, V5G 0A7 www.sparc.bc.ca [email protected] tel: 604-718-7733 i knowledge dissemination & exchange activities on homelessness Acknowledgements This project could not have been completed without the contributions of a host of staff members from municipalities throughout BC. Our appreciation to all the municipal housing planners who took the time to complete our survey, with special gratitude to those who also participated in our key informant interviews. A special thanks to the interns and volunteers who assisted with the background research: Carrie Smith, Raphael Santurette and Keith Leung. The resources of a number of organizations proved particularly helpful, including BC Housing, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Metro Vancouver, and Smart Growth BC, and we thank these agencies for making their research materials available. -

Metro Manila AFFILIATED HOSPITALS, CLINICS & Tel No: (02) 874 2506 / (02) 874 HOSPITAL of the INFANT JESUS SAN RAMON HOSPITAL INC

LAS PIÑAS Tel No.: (02) 682 2222 ADVENTIST MANILA MEDICAL Quezon Ave cor. Sct Magbanua, EAST MANILA HOSPITAL Blanket accreditation of all doctors CENTER Diliman, Quezon City MANAGERS CORP (OUR LADY OF 1975 Donada St., Pasay City Tel No: (02) 3723825 ALABANG MEDICAL CLINIC LOURDES HOSPITAL) SALVE REGINA HOSPITAL Tel. No: (02) 5259191 (Las Piñas Branch) Alabang –Zapote Sta. Mesa, Manila Marcos Hi-Way, Marikina City; Blanket accreditation with doctors DE LOS SANTOS MEDICAL CENTER Road Cor. Pelayo Village Talon, Las Tel No: (02) 716-8001 to 20 Trunkline: 477-4832/ 477-4847 201 E Rodriguez Sr. Ave, Quezon Piñas City SAN JUAN DE DIOS EDUCATIONAL City, 1112 Metro Manila AFFILIATED HOSPITALS, CLINICS & Tel No: (02) 874 2506 / (02) 874 HOSPITAL OF THE INFANT JESUS SAN RAMON HOSPITAL INC. FOUNDATION INC. HOSPITAL Tel. No: 893 5762 DENTISTS as of (April 29, 2019) 0164 / 0925 729 5550 Laong Laan Road, Sampaloc, 108 Gen.Ordonez, Marikina, 1811 Roxas Boulevard, Pasay City; Blanket accreditation with doctors Manila MMla; Trunkline: 831-9731, 831-6921 DILIMAN DOCTORS HOSPITAL Please call/text our 24/7 HOTLINE Tel. No: 7312771 Blanket accreditation of doctors 251 Commonwealth Ave, ALABANG MEDICAL CLINIC Blanket Accreditation with Doctors Tel No: (02) 941 8632 Matandang Balara, Quezon City, numbers for proper endorsement PASIG (Almanza Branch) 2F Susana Arcade 1119 Metro Manila GLOBE: 09778042137 #476 Real Street Almanza, Las Piñas MANILA DOCTORS HOSPITAL ST. VICTORIA HOSPITAL Tel. No (02) 883 6900 SUN: 09256521927 City United Nation Avenue, Malate, J.P.Rizal, Marikina, Metro Manila; MEDCOR PASIG HOSPITAL AND PLDT: 02 (2084611) Tel No: (02) 800 3840 / (02) 800 Manila; Trunkline: 942-2022 MEDICAL CENTER / MARIKINA DR. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP.