MF2582 Soybean Aphid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soybean Aphid Establishment in Georgia

Soybean Aphid Establishment in Georgia R. M. McPherson, Professor, Entomology J.C. Garner, Research Station Superintendent, Georgia Mountain Research and Education Center, Blairsville, GA P. M. Roberts, Extension Entomologist - Cotton & Soybean The soybean aphid, Aphis glycines Matsumura, has (nymphs) through parthenogenesis (reproduction by direct become a major new invasive pest species in North America. growth of egg-cells without male fertilization). Several It was first detected on Wisconsin soybeans during the generations of both winged and wingless female aphids are summer of 2000. By the end of the 2001 growing season, produced on soybeans during the summer. As soybeans begin soybean aphid populations were observed from New York to mature, both male and female winged aphids are produced. westward to Ontario, Canada, the Dakotas, Nebraska They migrate back to buckthorn where they mate and the and Kansas and southward to Missouri, Kentucky and females lay the overwintering eggs, thus starting the annual Virginia. By 2009 it had been detected in most of the cycle all over again. soybean-producing states in the U.S. On September 10 and October 1, 2002, during monthly field sampling of soybeans at the Georgia Mountain Research and Education Center in Blairsville, Ga., several small colonies of soybean aphids (eight to 10 aphids per leaf) were collected. Aphid identification was verified by Susan Halbert, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Fla. Soybean aphids have been observed on soybeans in Union County, Ga., (Blairsville) Photo 1. Colony of soybean aphids on a every year since 2002 and in several other Georgia counties in soybean leaf. -

Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management Kelley Tilmon ([email protected]) Buyung Hadi ([email protected]) The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) is a significant insect pest of soybean in the North Central region of the U.S., and if left untreated can reduce regional production values by as much as $2.4 billion annually (Song et al., 2006). The soybean aphid is an invasive pest that is native to eastern Asia, where soybean was first domesticated. The pest was first detected in the U.S. in 2000 (Tilmon et al., 2011) and in South Dakota in 2001. It quickly spread across 22 states and three Canadian provinces. Soybean aphid populations have the potential to increase rapidly and reduce yields (Hodgson et al., 2012). This chapter reviews the identification, biology and management of soybean aphid. Treatment thresholds, biological control, host plant resistance, and other factors affecting soybean aphid populations will also be discussed. Table 35.1 provides suggestions to lessen the financial impact of aphid damage. Table 35.1. Keys to reducing economic losses from aphids. • Use resistant aphid varieties; several are now available. • Monitor closely because populations can increase rapidly. • Soybean near buckthorn should be scouted first. • Adults can be winged or wingless • Determine if your field contains any biocontrol agents (especially lady beetles). • Control if the population exceeds 250 aphids/plant. CHAPTER 35: Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management 1 Description Adult soybean aphids can occur in either winged or wingless forms. Wingless aphids are adapted to maximize reproduction, and winged aphids are built to disperse and colonize other locations. -

Natural Resources

Plants That Cause Problems – “Invasive Species” DestinationOakland.com STOP! What is an Invasive Species? Imagine spring wildflowers covered with a mat of twisted green vines. This is a sign that Oakland County Offenders invasive plants have moved in and native species have moved out. Invasive plant species originate in other parts of the world and are introduced into to the United States through flower a variety of ways. Not all plants introduced from other countries become invasive. The term invasive species is reserved for plants that grow and reproduce rapidly, causing changes to the areas where they become established. Invasive species impact our health, our economy seed and the environment, and can cost the United States $120 billion annually! flower pod flower A Ticking Time Bomb Growing unnoticed at first, invasive species spread and cover the landscape. They change the seed pod fruit ecology, affecting wildlife communities and the soil. Over time, invasive plant species form a monoculture in which the only plant growing is the invasive plant. Plants with Super Powers Invasive species have super powers to alter the ecological balance of nature. They flourish seed because controls in their native lands do not exist here. The Nature Conservancy ranks invasive species as the second leading cause of species extinction worldwide. Negative Effects of Invasive Species • Changes in hydrology— seed dispersal wetlands dry out • Release of chemicals into the soil that inhibit Black Swallow-wort Cynanchum louiseae & the growth of other plants. This is known as Pale Swallow-wort Cynanchum rossicum Autumn Olive Elaeagnus umbellate Garlic Mustard Allaria periolata Allelopathy. -

Tracking the Role of Alternative Prey in Soybean Aphid Predation

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 4390–4400 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03482.x TrackingBlackwell Publishing Ltd the role of alternative prey in soybean aphid predation by Orius insidiosus: a molecular approach JAMES D. HARWOOD,* NICOLAS DESNEUX,†§ HO JUNG S. YOO,†¶ DANIEL L. ROWLEY,‡ MATTHEW H. GREENSTONE,‡ JOHN J. OBRYCKI* and ROBERT J. O’NEIL† *Department of Entomology, University of Kentucky, S-225 Agricultural Science Center North, Lexington, Kentucky 40546-0091, USA, †Department of Entomology, Purdue University, Smith Hall, 901 W. State Street, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2089, USA, ‡USDA-ARS, Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory, BARC-West, Beltsville, Maryland 20705, USA Abstract The soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is a pest of soybeans in Asia, and in recent years has caused extensive damage to soybeans in North America. Within these agroecosystems, generalist predators form an important component of the assemblage of natural enemies, and can exert significant pressure on prey populations. These food webs are complex and molecular gut-content analyses offer nondisruptive approaches for exam- ining trophic linkages in the field. We describe the development of a molecular detection system to examine the feeding behaviour of Orius insidiosus (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) upon soybean aphids, an alternative prey item, Neohydatothrips variabilis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), and an intraguild prey species, Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Specific primer pairs were designed to target prey and were used to examine key trophic connections within this soybean food web. In total, 32% of O. insidiosus were found to have preyed upon A. glycines, but disproportionately high consumption occurred early in the season, when aphid densities were low. -

Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 35: Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management Kelley Tilmon Buyung Hadi The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) is a significant insect pest of soybean in the North Central region of the U.S., and if left untreated can reduce regional production values by as much as $2.4 billion annually (Song et al., 2006). The soybean aphid is an invasive pest that is native to eastern Asia, where soybean was first domesticated. The pest was first detected in the U.S. in 2000 (Tilmon et al., 2011) and in South Dakota in 2001. It quickly spread across 22 states and three Canadian provinces. Soybean aphid populations have the potential to increase rapidly and reduce yields (Hodgson et al., 2012). This chapter reviews the identification, biology, and management of soybean aphid. Treatment thresholds, biological control, host plant resistance, and other factors affecting soybean aphid populations will also be discussed. Table 35.1 provides suggestions to lessen the financial impact of aphid damage. Table 35.1. Keys to reducing economic losses from aphids. • Use resistant aphid varieties; several are now available. • Monitor closely because populations can increase rapidly. • Soybean near buckthorn should be scouted first. • Adults can be winged or wingless • Determine if your field contains any biocontrol agents (especially lady beetles). • Control if the population exceeds 250 aphids/plant. 35-293 extension.sdstate.edu | © 2019, South Dakota Board of Regents Description Adult soybean aphids can occur in either winged or wingless forms. Wingless aphids are adapted to maximize reproduction, and winged aphids are built to disperse and colonize other locations. -

Recommended IPM Approach and Treatment Threshold for Soybean Aphid Control in Soybean

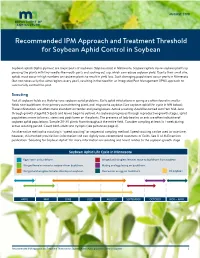

AUGUST 2018 Recommended IPM Approach and Treatment Threshold for Soybean Aphid Control in Soybean Soybean aphids (Aphis glycines) are major pests of soybeans (Glycines max) in Minnesota. Soybean aphids injure soybean plants by piercing the plants with tiny needle-like mouth parts and sucking out sap, which can reduce soybean yield. Due to their small size, aphids must occur in high numbers on soybean plants to result in yield loss. Such damaging populations occur yearly in Minnesota (but not necessarily the same regions every year), resulting in the need for an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach to successfully control this pest. Scouting Not all soybean fields are likely to have soybean aphid problems. Early aphid infestations in spring are often found in smaller fields near buckthorn, their primary overwintering plant, and migrate to soybean (See soybean aphid life-cycle in MN below). These infestations are often more abundant on tender and young leaves. Active scouting should be carried out from Mid-June through growth stage R6.5 (pods and leaves begin to yellow). As soybean progresses through reproductive growth stages, aphid populations move to leaves, stems and pods lower on the plants. The presence of lady beetles or ants are often indicative of soybean aphid populations. Sample 20-30 plants from throughout the entire field. Consider sampling at least 1x / week during active scouting period. Count both adults and nymphs (see picture on page 4). An alternative method to scouting is “speed scouting” or sequential sampling method. Speed scouting can be used to save time, however, this method provides less information and can slightly over-recommend treatment of fields. -

The Habitat Preference of the Invasive Common Buckthorn in West Holland Sub-Watershed, Ontario

The Habitat Preference of The Invasive Common Buckthorn in West Holland Sub-watershed, Ontario by Ying Hong A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Forest Conservation Faculty of Forestry University of Toronto © Copyright by Ying Hong 2018 The Habitat Preference of The Invasive Common Buckthorn in West Holland Sub-watershed, Ontario Ying Hong Master of Forest Conservation Faculty of Forestry University of Toronto 2018 Abstract The project objective is to examine the habitat preference of the invasive common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) in West Holland Sub-watershed located in the Lake Simcoe Watershed in Ontario. Filed data from monitoring plots, dispersed throughout the West Holland, were collected as part of the natural cover monitoring in the watershed during the summer of 2017. In my capstone project, I will 1) examine the possible plot characteristics that are related to common buckthorn presence; 2) explore whether and how common buckthorn abundance is related to the plot characteristics and disturbance; 3) determine the relationship between common buckthorn and other plants in the plot; and 4) give recommendations regard to current common buckthorn issue. This research can improve the knowledge of the invasive common buckthorn in Lake Simcoe Watershed, which is crucial because the non-native common buckthorn is distributed extensively across southern Ontario. ii Acknowledgments I want to say thank you to everyone who gives me physical or/and mental support! Thanks to my supervisor Dr. Danijela Puric-Mladenovic offer me summer job and give me lots of help and advice on the capstone project, and my crew leader Kyle Vanin from whom I learn a lot in the field; thanks, Katherine Baird help me with GIS; thanks to other VSP crews for collecting data together; and thanks to OMNR, especially my external supervisor Melanie Shapiera and Alex Kissel; thanks, Steve Varga, Richard Dickinson, Dave Bradley, Wasyl Bakowsky, Bodhan Kowalyk. -

The Effects of Isoprene Emission from Native and Invasive Trees on Local Air Quality

DePaul Discoveries Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 6 2017 The Effects of Isoprene Emission from Native and Invasive Trees on Local Air Quality Aarti P. Mistry DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/depaul-disc Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Forest Management Commons, Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, Other Plant Sciences Commons, and the Weed Science Commons Recommended Citation Mistry, Aarti P. (2017) "The Effects of Isoprene Emission from Native and Invasive Trees on Local Air Quality," DePaul Discoveries: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/depaul-disc/vol6/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Science and Health at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Discoveries by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effects of Isoprene Emission from Native and Invasive Trees on Local Air Quality Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge Dr. Mark Potosnak. This article is available in DePaul Discoveries: https://via.library.depaul.edu/depaul-disc/vol6/iss1/6 Mistry: Isoprene Emissions from Native and Invasive Trees on Air Quality The Effects of Isoprene Emission from Native and Invasive Trees on Local Air Quality Aarti Mistry* Department of Environmental Studies and Science Mark Potosnak, PhD; Faculty Advisor Department of Environmental Studies and Science ABSTRACT Biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) are the most abundant category of reactive gasses emitted into the atmosphere by the biosphere. -

Plant Conservation Alliance®S Alien Plant Working Group Common

FACT SHEET: COMMON BUCKTHORN Common Buckthorn Rhamnus cathartica L. Buckthorn family (Rhamnaceae) NATIVE RANGE Eurasia DESCRIPTION Common buckthorn is a shrub or small tree that can grow to 22 feet in height and have a trunk up to 10 inches wide. The crown shape of mature plants is spreading and irregular. The bark is gray to brown, rough textured when mature and may be confused with that of plum trees in the genus Prunus. When cut, the inner bark is yellow and the heartwood, pink to orange. Twigs are often tipped with a spine. In spring, dense clusters of 2 to 6, yellow-green, 4-petaled flowers emerge from stems near the bases of leaf stalks. Male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. Small black fruits about ¼ inch in cross-section and containing 3-4 seeds, form in the fall. Leaves are broadly oval, rounded or pointed at the tip, with 3-4 pairs of upcurved veins, and have jagged, toothed margins. The upper and lower leaf surfaces are without hairs. Leaves appear dark, glossy green on the upper surface and stay green late into fall, after most other deciduous leaves have fallen. A similar problem exotic species is Rhamnus frangula, glossy buckthorn. Glossy buckthorn does not have a spine at twig tips, leaves are not toothed, and the undersides of the leaves are hairy. NOTE: Several native American buckthorns that occur in the eastern U.S. that could be confused with the exotic species. If in doubt, consult with a knowledgeable botanist to get an accurate identification. -

Insect Communities in Soybeans of Eastern South Dakota: the Effects

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2013 Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies Jonathan G. Lundgren USDA-ARS, [email protected] Louis S. Hesler USDA-ARS Sharon A. Clay South Dakota State University, [email protected] Scott F. Fausti South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Part of the Agriculture Commons Lundgren, Jonathan G.; Hesler, Louis S.; Clay, Sharon A.; and Fausti, Scott F., "Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies" (2013). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 1164. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/1164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crop Protection 43 (2013) 104e118 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Crop Protection journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies Jonathan G. Lundgren a,*, Louis S. Hesler a, Sharon A. Clay b, Scott F. -

Aphid Vectors Impose a Major Bottleneck on Soybean Dwarf Virus Populations for Horizontal Transmission in Soybean Bin Tian1,2* , Frederick E

Tian et al. Phytopathology Research (2019) 1:29 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-019-0037-3 Phytopathology Research RESEARCH Open Access Aphid vectors impose a major bottleneck on Soybean dwarf virus populations for horizontal transmission in soybean Bin Tian1,2* , Frederick E. Gildow1, Andrew L. Stone3, Diana J. Sherman3, Vernon D. Damsteegt3,4 and William L. Schneider3,4* Abstract Many RNA viruses have genetically diverse populations in a single host. Important biological characteristics may be related to the levels of diversity, including adaptability, host specificity, and host range. Shifting the virus between hosts might result in a change in the levels of diversity associated with the new host. The level of genetic diversity for these viruses is related to host, vector and virus interactions, and understanding these interactions may facilitate the prediction and prevention of emerging viral diseases. It is known that luteoviruses have a very specific interaction with aphid vectors. Previous studies suggested that there may be a tradeoff effect between the viral adaptation and aphid transmission when Soybean dwarf virus (SbDV) was transmitted into new plant hosts by aphid vectors. In this study, virus titers in different aphid vectors and the levels of population diversity of SbDV in different plant hosts were examined during multiple sequential aphid transmission assays. The diversity of SbDV populations revealed biases for particular types of substitutions and for regions of the genome that may incur mutations among different hosts. Our results suggest that the selection on SbDV in soybean was probably leading to reduced efficiency of virus recognition in the aphid which would inhibit movement of SbDV through vector tissues known to regulate the specificity relationship between aphid and virus in many systems. -

Norway Maple Ailanthus Altissima – Tree of Heaven

TREESTREES • broadly winged samaras • milky sap • stout twigs • broad leaves, green on both sides • winter buds with only 4-6 scales Acer platanoides –Norway Maple Ailanthus altissima – tree of heaven •compound leaves with up to 40 leaflets •Leaflets entire except for 1-2 remnant teeth at base •Bruised foliage and twigs smell horrible •Fruits a samara similar to maple fruit •Fruits turn rusty brown •Bark smooth gray SHRUBS Berberis vulgaris – common barberry •Thorny fountain shaped shrub •Multi-parted thorn at each flush of leaves •Flowers held in a drooping raceme •Fruit a red drupe •Flowers golden yellow •Leaves bristle toothed Elaeagnus angustifolia – Russian olive •Often confused with autumn olive •No known escaped population in New England •Flowers yellow •Leaves silvery on both sides •Fruits yellow or dull red •Branches and stems heavily armed with true thorns Elaeagnus umbellata – autumn olive •15 to 20 foot high shrub •Prefers dry nutrient poor soils •Similar to willows from a distance •Leaves green on top and silver beneath •Flowers cream colored and very fragrant •Fruit a red berry appearing as if sprinkled with glitter •Young twigs have prominent yellow resin dots •Small tree/shrub, 15 to 20 ft. •Hard to distinguish •Leaves entire and egg-shaped •Flowers white, May- September •Fruit blue-black, June-October •Bark marked with white lenticels •Can confuse with alders or cherries – both have toothed leaves •Roots red Frangula alnus – glossy buckthorn Ligustrum obtusifolium –border privet •Need flowers to absolutely identify •Flowers