Soybean Aphid Host Range and Virus Transmission Efficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soybean Aphid Establishment in Georgia

Soybean Aphid Establishment in Georgia R. M. McPherson, Professor, Entomology J.C. Garner, Research Station Superintendent, Georgia Mountain Research and Education Center, Blairsville, GA P. M. Roberts, Extension Entomologist - Cotton & Soybean The soybean aphid, Aphis glycines Matsumura, has (nymphs) through parthenogenesis (reproduction by direct become a major new invasive pest species in North America. growth of egg-cells without male fertilization). Several It was first detected on Wisconsin soybeans during the generations of both winged and wingless female aphids are summer of 2000. By the end of the 2001 growing season, produced on soybeans during the summer. As soybeans begin soybean aphid populations were observed from New York to mature, both male and female winged aphids are produced. westward to Ontario, Canada, the Dakotas, Nebraska They migrate back to buckthorn where they mate and the and Kansas and southward to Missouri, Kentucky and females lay the overwintering eggs, thus starting the annual Virginia. By 2009 it had been detected in most of the cycle all over again. soybean-producing states in the U.S. On September 10 and October 1, 2002, during monthly field sampling of soybeans at the Georgia Mountain Research and Education Center in Blairsville, Ga., several small colonies of soybean aphids (eight to 10 aphids per leaf) were collected. Aphid identification was verified by Susan Halbert, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, Fla. Soybean aphids have been observed on soybeans in Union County, Ga., (Blairsville) Photo 1. Colony of soybean aphids on a every year since 2002 and in several other Georgia counties in soybean leaf. -

Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management Kelley Tilmon ([email protected]) Buyung Hadi ([email protected]) The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) is a significant insect pest of soybean in the North Central region of the U.S., and if left untreated can reduce regional production values by as much as $2.4 billion annually (Song et al., 2006). The soybean aphid is an invasive pest that is native to eastern Asia, where soybean was first domesticated. The pest was first detected in the U.S. in 2000 (Tilmon et al., 2011) and in South Dakota in 2001. It quickly spread across 22 states and three Canadian provinces. Soybean aphid populations have the potential to increase rapidly and reduce yields (Hodgson et al., 2012). This chapter reviews the identification, biology and management of soybean aphid. Treatment thresholds, biological control, host plant resistance, and other factors affecting soybean aphid populations will also be discussed. Table 35.1 provides suggestions to lessen the financial impact of aphid damage. Table 35.1. Keys to reducing economic losses from aphids. • Use resistant aphid varieties; several are now available. • Monitor closely because populations can increase rapidly. • Soybean near buckthorn should be scouted first. • Adults can be winged or wingless • Determine if your field contains any biocontrol agents (especially lady beetles). • Control if the population exceeds 250 aphids/plant. CHAPTER 35: Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management 1 Description Adult soybean aphids can occur in either winged or wingless forms. Wingless aphids are adapted to maximize reproduction, and winged aphids are built to disperse and colonize other locations. -

Tracking the Role of Alternative Prey in Soybean Aphid Predation

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 4390–4400 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03482.x TrackingBlackwell Publishing Ltd the role of alternative prey in soybean aphid predation by Orius insidiosus: a molecular approach JAMES D. HARWOOD,* NICOLAS DESNEUX,†§ HO JUNG S. YOO,†¶ DANIEL L. ROWLEY,‡ MATTHEW H. GREENSTONE,‡ JOHN J. OBRYCKI* and ROBERT J. O’NEIL† *Department of Entomology, University of Kentucky, S-225 Agricultural Science Center North, Lexington, Kentucky 40546-0091, USA, †Department of Entomology, Purdue University, Smith Hall, 901 W. State Street, West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2089, USA, ‡USDA-ARS, Invasive Insect Biocontrol and Behavior Laboratory, BARC-West, Beltsville, Maryland 20705, USA Abstract The soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is a pest of soybeans in Asia, and in recent years has caused extensive damage to soybeans in North America. Within these agroecosystems, generalist predators form an important component of the assemblage of natural enemies, and can exert significant pressure on prey populations. These food webs are complex and molecular gut-content analyses offer nondisruptive approaches for exam- ining trophic linkages in the field. We describe the development of a molecular detection system to examine the feeding behaviour of Orius insidiosus (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) upon soybean aphids, an alternative prey item, Neohydatothrips variabilis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), and an intraguild prey species, Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Specific primer pairs were designed to target prey and were used to examine key trophic connections within this soybean food web. In total, 32% of O. insidiosus were found to have preyed upon A. glycines, but disproportionately high consumption occurred early in the season, when aphid densities were low. -

Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 35: Soybean Aphid Identification, Biology, and Management Kelley Tilmon Buyung Hadi The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) is a significant insect pest of soybean in the North Central region of the U.S., and if left untreated can reduce regional production values by as much as $2.4 billion annually (Song et al., 2006). The soybean aphid is an invasive pest that is native to eastern Asia, where soybean was first domesticated. The pest was first detected in the U.S. in 2000 (Tilmon et al., 2011) and in South Dakota in 2001. It quickly spread across 22 states and three Canadian provinces. Soybean aphid populations have the potential to increase rapidly and reduce yields (Hodgson et al., 2012). This chapter reviews the identification, biology, and management of soybean aphid. Treatment thresholds, biological control, host plant resistance, and other factors affecting soybean aphid populations will also be discussed. Table 35.1 provides suggestions to lessen the financial impact of aphid damage. Table 35.1. Keys to reducing economic losses from aphids. • Use resistant aphid varieties; several are now available. • Monitor closely because populations can increase rapidly. • Soybean near buckthorn should be scouted first. • Adults can be winged or wingless • Determine if your field contains any biocontrol agents (especially lady beetles). • Control if the population exceeds 250 aphids/plant. 35-293 extension.sdstate.edu | © 2019, South Dakota Board of Regents Description Adult soybean aphids can occur in either winged or wingless forms. Wingless aphids are adapted to maximize reproduction, and winged aphids are built to disperse and colonize other locations. -

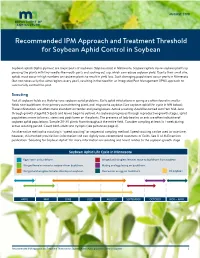

Recommended IPM Approach and Treatment Threshold for Soybean Aphid Control in Soybean

AUGUST 2018 Recommended IPM Approach and Treatment Threshold for Soybean Aphid Control in Soybean Soybean aphids (Aphis glycines) are major pests of soybeans (Glycines max) in Minnesota. Soybean aphids injure soybean plants by piercing the plants with tiny needle-like mouth parts and sucking out sap, which can reduce soybean yield. Due to their small size, aphids must occur in high numbers on soybean plants to result in yield loss. Such damaging populations occur yearly in Minnesota (but not necessarily the same regions every year), resulting in the need for an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach to successfully control this pest. Scouting Not all soybean fields are likely to have soybean aphid problems. Early aphid infestations in spring are often found in smaller fields near buckthorn, their primary overwintering plant, and migrate to soybean (See soybean aphid life-cycle in MN below). These infestations are often more abundant on tender and young leaves. Active scouting should be carried out from Mid-June through growth stage R6.5 (pods and leaves begin to yellow). As soybean progresses through reproductive growth stages, aphid populations move to leaves, stems and pods lower on the plants. The presence of lady beetles or ants are often indicative of soybean aphid populations. Sample 20-30 plants from throughout the entire field. Consider sampling at least 1x / week during active scouting period. Count both adults and nymphs (see picture on page 4). An alternative method to scouting is “speed scouting” or sequential sampling method. Speed scouting can be used to save time, however, this method provides less information and can slightly over-recommend treatment of fields. -

Insect Communities in Soybeans of Eastern South Dakota: the Effects

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2013 Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies Jonathan G. Lundgren USDA-ARS, [email protected] Louis S. Hesler USDA-ARS Sharon A. Clay South Dakota State University, [email protected] Scott F. Fausti South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Part of the Agriculture Commons Lundgren, Jonathan G.; Hesler, Louis S.; Clay, Sharon A.; and Fausti, Scott F., "Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies" (2013). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 1164. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/1164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crop Protection 43 (2013) 104e118 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Crop Protection journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Insect communities in soybeans of eastern South Dakota: The effects of vegetation management and pesticides on soybean aphids, bean leaf beetles, and their natural enemies Jonathan G. Lundgren a,*, Louis S. Hesler a, Sharon A. Clay b, Scott F. -

Aphid Vectors Impose a Major Bottleneck on Soybean Dwarf Virus Populations for Horizontal Transmission in Soybean Bin Tian1,2* , Frederick E

Tian et al. Phytopathology Research (2019) 1:29 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42483-019-0037-3 Phytopathology Research RESEARCH Open Access Aphid vectors impose a major bottleneck on Soybean dwarf virus populations for horizontal transmission in soybean Bin Tian1,2* , Frederick E. Gildow1, Andrew L. Stone3, Diana J. Sherman3, Vernon D. Damsteegt3,4 and William L. Schneider3,4* Abstract Many RNA viruses have genetically diverse populations in a single host. Important biological characteristics may be related to the levels of diversity, including adaptability, host specificity, and host range. Shifting the virus between hosts might result in a change in the levels of diversity associated with the new host. The level of genetic diversity for these viruses is related to host, vector and virus interactions, and understanding these interactions may facilitate the prediction and prevention of emerging viral diseases. It is known that luteoviruses have a very specific interaction with aphid vectors. Previous studies suggested that there may be a tradeoff effect between the viral adaptation and aphid transmission when Soybean dwarf virus (SbDV) was transmitted into new plant hosts by aphid vectors. In this study, virus titers in different aphid vectors and the levels of population diversity of SbDV in different plant hosts were examined during multiple sequential aphid transmission assays. The diversity of SbDV populations revealed biases for particular types of substitutions and for regions of the genome that may incur mutations among different hosts. Our results suggest that the selection on SbDV in soybean was probably leading to reduced efficiency of virus recognition in the aphid which would inhibit movement of SbDV through vector tissues known to regulate the specificity relationship between aphid and virus in many systems. -

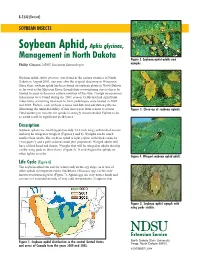

Soybean Aphid, Aphis Glycines

E-1232 (Revised) SOYBEAN INSECTS Soybean Aphid, Aphis glycines, Management in North Dakota Figure 2. Soybean aphid adults and Phillip Glogoza, NDSU Extension Entomologist nymphs. Soybean aphid, Aphis glycines, was found in the eastern counties of North Dakota in August 2001, one year after the original discovery in Wisconsin. Since then, soybean aphid has been found on soybean plants in North Dakota as far west as the Missouri River, though their overwintering survival may be limited to areas in the more eastern counties of the state. Though no economic infestations were found during the 2001 season, fields that had significant infestations warranting treatment to limit yield losses were treated in 2002 and 2003. Further, each of those seasons had different infestation patterns, illustrating the unpredictability of this insect pest from season to season. Figure 3. Close-up of soybean aphids. Field scouting to monitor for aphids is strongly recommended. Failure to do so could result in significant yield losses. Description Soybean aphids are small (approximately 1/16 inch long) soft-bodied insects and may be winged or wingless (Figures 2 and 3). Nymphs can be much smaller than adults. The soybean aphid is light yellow with black cornicles (“tail-pipes”) and a pale colored cauda (tail projection). Winged adults will have a black head and thorax. Nymphs that will be winged as adults develop visible wing pads on their thorax (Figure 5). In mid August the aphids are often lighter in color. Figure 4. Winged soybean aphid adult. Life Cycle (Figure 6) The soybean aphid can survive winter only in the egg stage, as is true of other aphids in temperate zones. -

Field Crops Department of Entomology

PURDUE EXTENSION E-217-W Field Crops Department of Entomology SOYBEAN APHID Christian H. Krupke, John L. Obermeyer, and Larry W. Bledsoe, Extension Entomologists In 2000, a new insect, the soybean aphid, Aphis glycines Matsumura, was discovered in soybean fields in many areas of the Midwest, including Indiana. Researchers do not know how, when, or where this exotic species entered the US, but since its discovery it has caused significant damage to Indiana soybean fields in 2001 and 2003. This publication summarizes what we know about soybean aphid biology and provides recommendations for scouting and making treatment decisions. The soybean aphid (Fig. 1) is a small yellow aphid with distinct black cornicles, often known as “tailpipes” (Fig. 2). Without careful inspection (10X magnification), they can be confused with other small arthropods living on soybean, including spider mites, thrips, and leafhoppers Fig. 2. Soybean aphid cornicles (Photo Credit: (Figs. 3a, b, c). Soybean aphid is native to Asia, and its current Ho Jung Yoo, Purdue University) distribution includes China, Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Australia, and Eastern Russia. In July of on soybean, the first report of this species in North America. 2000, researchers in Wisconsin discovered aphids feeding By the end of the 2000 growing season, soybean aphid was confirmed in eight Midwestern states. In Indiana, the aphid was found in low numbers on soybean in every county surveyed. The soybean aphid’s present distribution extends throughout the Midwest, much of the Great Plains’ states, and east to the Atlantic coast (Fig. 4). Damage and Symptoms The soybean aphid feeds using needle-like, sucking mouthparts to remove plant sap (Fig. -

Soybean Aphid Management in Nebraska Tom E

® ® University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources Know how. Know now. G2063 Soybean Aphid Management in Nebraska Tom E. Hunt, Extension Entomology Specialist; Keith J. Jarvi, Extension Educator; Wayne J. Ohnesorg, Extension Educator; and Lanae M. Pierson, Entomology Graduate Research Assistant Learn about the soybean aphid, its identification, life cycle, and damage, as well as how to scout and man- age it. Photos of different stages and natural enemies are included. The soybean aphid (Aphis glycines) was introduced into the U.S. in 2000 and first found in Nebraska in 2002. Yield losses of over 30 percent have been documented in northeast Nebraska and over 40 percent in others areas of the north central United States. Soybean Aphid Description Figure 1. Soybean aphids with black tipped cornicles. (All figures by The soybean aphid is soft bodied, light green to pale James A. Kalisch, University of Nebraska–Lincoln Depart- ment of Entomology) yellow, less than 1/16 inch long, and has two black-tipped cornicles (cornicles look like tailpipes) on the rear of the abdomen (Figure 1). It has piercing-sucking mouthparts and typically feeds on new tissue on the undersides of leaves near the top of recently colonized soybean plants (Figure 2). Later in the season the aphids can be found on all parts of the plant, feeding primarily on the undersides of leaves, but also on the stems and pods. The soybean aphid is currently the only aphid in North America that forms colonies on soybean. Soybean Aphid Life Cycle The seasonal life cycle of the soybean aphid is complex with up to 18 generations a year. -

Emerging Disease, Insect, and Weed Pests in South Dakota Soybean Production

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 27: Emerging Disease, Insect, and Weed Pests in South Dakota Soybean Production Darrell Deneke Kelley Tilmon Connie L. Strunk ([email protected]) New pests are always around the corner. As with other crop species introduced from other parts of the world, the pests of these plants frequently follow the plant. Once here, these pests often thrive because they do not have their natural predators. A recent example of a pest following the soybean plant is the Asian soybean aphid. The soybean aphid was first documented in North America in July of 2000. From then, its population rapidly grew and it’s now part of the South Dakota soybean grower’s annual insect pest management. This chapter discusses emerging soybean disease, insect, and weed pests that may be of concern for South Dakota soybean growers. The emerging pests covered include frogeye leaf spot, sudden death syndrome, Asian soybean rust, brown marmorated stink bug, kudzu bug, and herbicide-resistant Palmer amaranth (pigweed). Frogeye Leaf Spot Frogeye leaf spot is a common foliar disease of the southern soybean-growing states. Typically, the disease can occur sporadically in the central states, but can be seen farther north when weather conditions are favorable. Frogeye leaf spot favors warm, humid weather for development. Spores are spread short distances by wind or splashing rain. Dry weather severely limits disease development. The disease period in South Dakota is July through August. Occurrence is considered rare and is mainly seen in the southeastern parts of state. Figure 27.1. Soybean leaf showing frogeye leaf spot lesions. -

For Biological Control of the Soybean Aphid, Aphis Glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), in the Continental United States

United States Department of Agriculture Field Release of Aphelinus Marketing and Regulatory glycinis (Hymenoptera: Programs Animal and Aphelinidae) for Biological Plant Health Inspection Service Control of the Soybean Aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), in the Continental United States Environmental Assessment, September 2012 Field Release of Aphelinus glycinis (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) for Biological Control of the Soybean Aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae), in the Continental United States Environmental Assessment, September 2012 Agency Contact: Shirley Wager-Page, Branch Chief Pest Permitting Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Road, Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737–1236 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720–2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326–W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250–9410 or call (202) 720–5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Mention of companies or commercial products in this report does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) over others not mentioned. USDA neither guarantees or warrants the standard of any product mentioned. Product names are mentioned solely to report factually on available data and to provide specific information.