ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

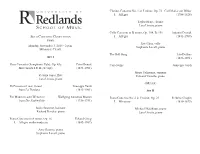

Delius Sea Drift • Songs of Farewell • Songs of Sunset

DELIUS SEA DRIFT • SONGS OF FAREWELL • SONGS OF SUNSET Bournemouth Symphony Bryn Terfel baritone Orchestra with Choirs Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Frederick Delius (1862 – 1934) 1 Sea Drift* 26:00 for baritone, chorus, and orchestra Songs of Farewell 18:04 for double chorus and orchestra 2 I Double Chorus: ‘How sweet the silent backward tracings!’ 4:28 3 II Chorus: ‘I stand as on some mighty eagle’s beak’ 4:39 4 III Chorus: ‘Passage to you! O secret of the earth and sky!’ 3:33 5 IV Double Chorus: ‘Joy, shipmate, joy!’ 1:31 6 V Chorus: ‘Now finalè to the shore’ 3:50 3 Songs of Sunset*† 32:59 for mezzo-soprano, baritone, chorus, and orchestra 7 Chorus: ‘A song of the setting sun!’ – 3:24 8 Soli: ‘Cease smiling, Dear! a little while be sad’ – 4:46 9 Chorus: ‘Pale amber sunlight falls…’ – 4:26 10 Mezzo-soprano: ‘Exceeding sorrow Consumeth my sad heart!’ – 3:43 11 Baritone: ‘By the sad waters of separation’ – 4:49 12 Chorus: ‘See how the trees and the osiers lithe’ – 3:35 13 Baritone: ‘I was not sorrowful, I could not weep’ – 4:46 14 Soli, Chorus: ‘They are not long, the weeping and the laughter’ 3:34 TT 77:20 Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano† Bryn Terfel baritone* Waynflete Singers David Hill director Southern Voices Graham Caldbeck chorus master Members of the Bournemouth Symphony Chorus Neville Creed chorus master Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra Brendan O’Brien leader Richard Hickox 4 Delius: Sea Drift / Songs of Sunset / Songs of Farewell Sea Drift into which the chorus’s commentaries are Both Sea Drift (1903 – 04) and Songs of Sunset effortlessly intermingled. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

DELIUS BOOKLET:Bob.Qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1

DELIUS BOOKLET:bob.qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1 second piece, Summer Night on the River, is equally evocative, this time suggested by the river Loing that lay at the the story of a voodoo prince sold into slavery, based on an episode in the novel The Grandissimes by the American bottom of Delius’s garden near Fontainebleau, the kind of scene that might have been painted by some of the French writer George Washington Cable. The wedding dance La Calinda was originally a dance of some violence, leading to painters that were his contemporaries. hysteria and therefore banned. In the Florida Suite and again in Koanga it lacks anything of its original character. The opera Irmelin, written between 1890 and 1892, and the first attempt by Delius at the form, had no staged Koanga, a lyric drama in a prologue and three acts, was first heard in an incomplete concert performance at St performance until 1953, when Beecham arranged its production in Oxford. The libretto, by Delius himself, deals with James’s Hall in 1899. It was first staged at Elberfeld in 1904. With a libretto by Delius and Charles F. Keary, the plot The Best of two elements, Princess Irmelin and her suitors, none of whom please her, and the swine-herd who eventually wins is set on an eighteenth century Louisiana plantation, where the slave-girl Palmyra is the object of the attentions of her heart. The Prelude, designed as an entr’acte for the later opera Koanga, makes use of four themes from Irmelin. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

The Choral Cycle

THE CHORAL CYCLE: A CONDUCTOR‟S GUIDE TO FOUR REPRESENTATIVE WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY RUSSELL THORNGATE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. LINDA POHLY AND DR. ANDREW CROW BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 Contents Permissions ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction What Is a Choral Cycle? .............................................................................1 Statement of Purpose and Need for the Study ............................................4 Definition of Terms and Methodology .......................................................6 Chapter 1: Choral Cycles in Historical Context The Emergence of the Choral Cycle .......................................................... 8 Early Predecessors of the Choral Cycle ....................................................11 Romantic-Era Song Cycles ..................................................................... 15 Choral-like Genres: Vocal Chamber Music ..............................................17 Sacred Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era ................................20 Secular Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era .............................. 22 The Choral Cycle in the Twentieth Century ............................................ 25 Early Twentieth-Century American Cycles ............................................. 25 Twentieth-Century European Cycles ....................................................... 27 Later Twentieth-Century American -

A Village Romeo and Juliet the Song of the High Hills Irmelin Prelude

110982-83bk Delius 14/6/04 11:00 am Page 8 Also available on Naxos Great Conductors • Beecham ADD 8.110982-83 DELIUS A Village Romeo and Juliet The Song of the High Hills Irmelin Prelude Dowling • Sharp • Ritchie Soames • Bond • Dyer Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Sir Thomas Beecham Naxos Radio (Recorded 1946–1952) Over 50 Channels of Classical Music • Jazz, Folk/World, Nostalgia Accessible Anywhere, Anytime • Near-CD Quality www.naxosradio.com 2 CDs 8.110982-83 8 110982-83bk Delius 14/6/04 11:00 am Page 2 Frederick Delius (1862-1934) 5 Koanga: Final Scene 9:07 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra • Sir Thomas Beecham (1879-1961) (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus) Recorded on 26th January, 1951 Delians and Beecham enthusiasts will probably annotation, frequently content with just the notes. A Matrix Nos. CAX 11022-3, 11023-2B continue for ever to debate the relative merits of the score of a work by Delius marked by Beecham, First issued on Columbia LX 1502 earlier recordings made by the conductor in the 1930s, however, tells a different story, instantly revealing a mostly with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, in most sympathetically engaged music editor at work. comparison with those of the 1940s and 1950s Pulse, dynamics, phrasing, expressive nuance and All recordings made in Studio 1, Abbey Road, London recorded with handpicked players of the Royal articulation, together with an acute sensitivity to Transfers & Production: David Lennick Philharmonic Orchestra. Following these two major constantly changing orchestral balance, are annotated Digital Noise Reduction: K&A Productions Ltd. periods of activity, the famous EMI stereo remakes with painstaking practical detail to compliment what Original recordings from the collections of David Lennick, Douglas Lloyd and Claude G. -

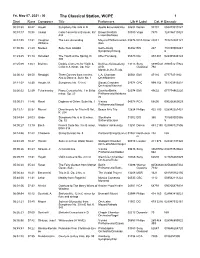

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Fri, May 07, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 30:47 Haydn Symphony No. 042 in D Apollo Ensemble/Hsu 02698 Dorian 90191 053479019127 00:33:1710:38 Vivaldi Cello Concerto in B minor, RV Brown/Scottish 03080 Virgo 7873 724356110328 424 Ensemble/Rees 00:44:5514:31 Vaughan The Lark Ascending Meyers/Philharmonia/L 03876 RCA Victor 23041 743212304121 Williams itton 01:00:5621:29 Nielsen Suite from Aladdin Gothenburg 06392 BIS 247 731859000247 Symphony/Chung 6 01:23:2501:14 Schubert The Youth at the Spring, D. Otter/Forsberg 05373 DG 453 481 028945348124 300 01:25:3933:03 Brahms Double Concerto for Violin & Bell/Isserlis/Academy 13113 Sony 88985321 889853217922 Cello in A minor, Op. 102 of St. Classical 792 Martin-in-the-Fields 02:00:1209:50 Respighi Three Dances from Ancient L.A. Chamber 00561 EMI 47116 07777471162 Airs & Dances, Suite No. 1 Orch/Marriner 02:11:02 14:30 Haydn, M. Symphony No. 12 in G Slovak Chamber 02578 CPO 999 154 761203915422 Orchestra/Warchal 02:26:3232:29 Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Gavrilov/Berlin 02074 EMI 49632 077774963220 minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Ashkena zy 03:00:3111:46 Ravel Daphnis et Chloe: Suite No. 1 Vienna 04578 RCA 68600 090266860029 Philharmonic/Maazel 03:13:1720:37 Mozart Divertimento for Trio in B flat, Beaux Arts Trio 12824 Philips 422 700 028942251427 K. 254 03:34:5424:03 Gade Symphony No. 6 in G minor, Stockholm 01002 BIS 355 731859000356 Op. -

January 29, 2018: (Full-Page Version) Close Window “Where Is All the Knowledge We Lost with Information?” — T

January 29, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “Where is all the knowledge we lost with information?” — T. S. Eliot Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Franck The Breezes (A Symphonic Poem) National Orchestra of Belgium/Cluytens EMI Classics 13207 Awake! Welsh National Opera POLYGRAM 00:13 Buy Now! Delius In a Summer Garden, a Rhapsody 430202 28943020220 Orchestra/MacKerras RECORDS 00:28 Buy Now! Schumann Fantasy in C, Op. 17 Alan Marks Nimbus 5181 083603518127 01:00 Buy Now! Sibelius Night Ride and Sunrise, Op. 55 Philharmonia Orchestra/Rattle EMI 47006 N/A 01:16 Buy Now! Scarlatti, A. Sinfonia No. 7 in G minor for flute and strings Bennett/I Musici Philips 434 160 028943416023 01:24 Buy Now! Nielsen Violin Concerto, Op. 33 Lin/Swedish Radio Symphony/Salonen Sony 44548 07464445482 02:01 Buy Now! Strauss Jr. Emperor Waltz Vienna Philharmonic/Maazel DG 289 459 730 028945973029 02:13 Buy Now! Beethoven Minuets Nos. 1-4 Bella Musica Ensemble of Vienna Harmonia Mundi 1901017 3149021610175 02:22 Buy Now! Dvorak Piano Trio No. 1 in B flat, Op. 21 Suk Trio Denon 1409 T4988001077237 03:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Flute Concerto in D, RV 90 "Il gardellino" Antonini/Il Giardino Armonico Milan Teldec 72367 090317326726 03:12 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ The Siege of Corinth Orchestra St. Cecilia/Pappano Warner Classics 0825646243440 825646243440 03:23 Buy Now! Reinecke Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 134 "Hakon Jarl" Tasmanian Symphony/Shelley Chandos 9893 095115989326 04:00 Buy Now! Brahms Symphony No. -

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2013, Number 153

The Delius Society Journal Spring 2013, Number 153 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) President Lionel Carley BA PhD Vice Presidents Roger Buckley Sir Andrew Davis CBE Sir Mark Elder CBE Bo Holten RaD Lyndon Jenkins RaD Richard Kitching Piers Lane BMus Hon FRAM ARCM LMusA David Lloyd-Jones BA Hon DMus FGSM Julian Lloyd Webber FRCM John McCabe CBE, Hon DMus Anthony Payne Robert Threlfall Website: http://www.delius.org.uk ISSN-0306-0373 1 DSJ 153 Spring 2013.indd 1 08/04/2013 09:45 Chairman Martin Lee-Browne CBE Chester House, Fairford Gloucestershire GL7 4AD Email: Chairman@The DeliusSociety.org.uk Treasurer and Membership Secretary Peter Watts c/o Bourner Bullock – Chartered Accountants Sovereign House 212-224 Shaftesbury Avenue London WC2 8HQ Email: [email protected] Secretary Lesley Buckley c/o Crosland Communications Ltd The Railway Station Newmarket CB8 9WT Tel: 07941 188617 Email: [email protected] Journal Editor Paul Chennell 19 Moriatry Close Holloway, London N7 0EF Tel: 020 7700 0646 Email: [email protected] Front cover: Paul Guinery unravelling Delius’s harmony, at the British Library on 22nd September 2012 Photo: Roger Buckley Back cover: 23rd September 2012 Andrew J. Boyle at the summit of Liahovda, where Delius had his last glimpse of Norway’s mountain majesty Photo: Andrew Boyle The Editor has tried in good faith to contact the holders of the copyright in all material used in this Journal (other than holders of it for material which has been specifically provided by agreement with the Editor), and to obtain their permission to reproduce it.