Employment Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Davie Update Volume 16 Issue 3

HOLIDAY EDITION 2019 | VOL. 16 DAVIETHE TOWN OF DAVIE’S UPDATEOFFICIAL NEWS MAGAZINE TOWN INFORMATION WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW HOLIDAY FESTIVITIES EVENTS, ACTIVITIES AND MORE! DAVIE UPDATE IN THIS ISSUE 5 Message from the Mayor 12 Parks, Recreation & Cultural Arts 6 Thoughts and Comments 15 Davie Aquatics & Fitness From the Davie Town Council 17 Events 7 Season of Giving 20 Police Updates 8 Together We Can Make a Difference 21 Fire Updates and HHW & Electronics Recycling 22 Out and About 10 Town Information 23 Employee Spotlight TOWN COUNCIL Pictured on the right 1 Mayor Judy Paul 2 Vice Mayor Caryl Hattan (District 2) 3 Councilmember Bryan Caletka (District 1) 4 Councilmember Susan Starkey (District 3) 5 Councilmember Marlon Luis (District 4) 1 2 3 3 THE DAVIE UPDATE The Davie Update is the official publication of the Town of Davie. The magazine is published three times per year and is mailed to residents within the Town under the direction of the Administration Department. The Davie Update also can be viewed on the web at 4 5 www.davie-fl.gov PAGE 2 PAGE The Town of Davie strives to be the ON THE Picture of Sunny Lake Bird Sanctuary located at preeminent community in South Florida COVER 5300 Griffin Road, Davie, FL to live, work, learn, and play while treasuring its preserved natural setting. ISSUE 3 | FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL @TOWNOFDAVIE TOWN ADMINISTRATION Town Administrator Richard J. Lemack Deputy Town Administrator Macciano K. Lewis Assistant Town Administrator Phillip R. Holste ___________ EDITORS Managing Editor Intergovernmental Affairs Manager 2019-2020 UPCOMING Leona Henry TOWN COUNCIL AND CRA MEETINGS 954-797-1035 [email protected] CRA November 6, 2019 6:00 p.m. -

Broward County Pioneer Day 2018

Broward County Historic Preservation Board presents 44TH ANNUAL PIONEER DAY &. ~ * "' ~. 2018 . l BR tWARD COUNTY FLORIDA FLORIDA HISTORIC PRESERVATION BOARD to the men and women who have been selected as Broward County Pioneers! FROM THE BROWARD COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS 44Tl-l ANNUAL PIONEER DAY ~ Broward County Historic Preservation Board presents the 44th Annual Pioneer Day Celebration Saturday, May 12th Davie Town Hall B~'>ci.WARD ~ COUNTY FLORIDA FLORIDA HISTORIC PRESERVATION BOARD Broward.org/History/PioneerDay Congratulations to the Broward County Historic Preservation Board as we celebrate the 44th Annual Pioneer Day event. This year we partner w ith t he Town of Davie who will host this special event at Davie City Hall; a beautiful venue in a beautiful city. The pioneer spirit is one that captures the imagination of us all. Pioneers explore new territories, exercise independent judgment, often in opposition to conventional w isdom and are risk takers willing to reach their goals through unconventional means. They have a vision of something better beyond their immediate world as they reject the status quo. Congratulations are in order for the men and women who have been selected as Broward County Pioneers. They jo in a group of over 2,000 other Pioneers the Commission has honored over past decades. Their visions and efforts have kept important pieces of Broward County's rich past intact for future generations to experience and appreciate. As we look to the future of Broward County and those who w ill make a lasting impact on our community; we express our g ratit ude and admirat ion for the pioneers of today and yesterday. -

Town of Davie Planning & Zoning Division

TOWN OF DAVIE PLANNING & ZONING DIVISION 6591 ORANGE DRIVE DAVIE, FLORIDA 33314-3399 Phone: 954.797.1103 www.davie-fl.gov MEMORANDUM TO: Planning and Zoning Board FROM: David Abramson, Deputy Planning & Zoning Manager THROUGH: David Quigley, Planning and Zoning Manager DATE: May 15, 2017 SUBJECT: Historic Preservation Ordinance BACKGROUND On September 23, 2014, the Broward County Board of County Commissioners enacted Ordinance (#2014-32) revising its historic preservation program to apply to both unincorporated areas and municipalities that have not established a local historical preservation ordinance. Consequently, Town staff has prepared a local ordinance that would add similar historic preservation regulations that are consistent with both federal and state requirements. Through this amendment, the Town could regulate its own program and establish criteria for designating historic and archaeological resources, as well as assist in pursuing Certified Local Government (CLG) status with the state. RECOMMENDATION Find that the proposed ordinance is consistent with and furthers the Town’s comprehensive plan and recommends as such to the Town Council. PZM_2017_25_(Historic_Preservation_Ord) .docx Pg. 1 of 1 HISTORIC PRESERVATION SUMMARY OF PROPOSAL No. Section Issue/Matter Proposal 1 2-73 Boards and Committees Create the Historic Preservation Board that 2-158 Establishes the authority and operations of Town includes the specifics of membership and duties. advisory boards/committees. 2 12-56 to Performance Standards Relocate archeological provisions within this 12-79 Regulates the intensity of development to the section into the proposed historic preservation natural capacity of a site that which otherwise may code. lead to the destruction of natural resources and wildlife habitats, as well as pollution of ground and surface water. -

Ron Bergeron Charitable Contributions

Charitable Donations American Cancer Society American Diabetes Association American Heart Association American Youth Soccer Organization Arthritis Foundation Aster Knight Parks Foundation Becca’s Closet Bergeron Everglades Museum Bergeron Park, Davie Bergeron Rodeo Grounds Books of Hope Boy Scouts of America Boys & Girls Club of Broward County Broward Cancer Society Broward County Airboat Association Broward County Career Days Broward County Pace Center for Girls Broward County Police Benevolent Association Broward County Police Memorial Broward County Sports Hall of Fame Broward Partnership for the Homeless Broward YMCA Schoarship Campaign Calvary Chapel Sawgrass Children’s Harbor Cooper City, Broward Sheriffs Office Crime Stoppers Broward County Davie Historical Society Davie Pro Rodeo Davie Rodeo Association Ducks Unlimited E.A.S.E. Foundation Five Star Championship Rodeo Florida Fish & Wildlife Florida High School Rodeo Association Florida Junior Rodeo Association Florida Sheriffs Youth Ranches Florida Special Olympics Florida Wrangler Rodeo Association Fort Lauderdale Historical Society Heart of Jonathon Heath Occupations Student of America Hispanic Unity Hispanic Women of Distinction Hollybrooke Gold Tournament Holy Ground Homeless Shelter Horses & Handicap In Jacob’s Shoes Jesen Beach High School Junior Achievement Junior League of Greater Fort Lauderdale Kentucky Employees Charitable Campaign Leadership Broward Foundation, Inc Memorial Hospital West Miramar Pembroke Pines Regional Chamber of Commerce Pinnacle Awards Muscular Dystrophy -

Broward County Historical Commission Awarded Historic Preservation Challenge Grants by David Baber

Broward County Historical Commission Awarded Historic Preservation Challenge Grants By David Baber Dave Baber has been the Administrator and Historic Preservation Officer of the Broward County Historical Commission since January of 2008. He has been active in historic preservation and grant administration over 30 years. n 2006, the Broward County Board of County Commissioners and the Broward County Historical ICommission created a grant program to assist the preservation of historic resources within the county owned by government or nonprofit organizations. $450,000 was allocated for grants between 2006 and 2008. As a result of this program, 11 historic sites throughout the county have The Annie Beck House in the been assisted. Project work for these grants fell into three 1950s. (Image courtesy of the Fort categories – repairing damage caused by the hurricanes Lauderdale Historical Society) of 2005, repairing general deterioration or reversing inappropriate alterations. What follows is a description of each project. The ANNIE BECK HOUSE, 1329 North Dixie Highway, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, owned by the Broward Trust for Historic Preservation, Inc., received a grant of $42,240.00. This craftsman bungalow house was built in 1916 of Dade County pine by Fort Lauderdale pioneers Dr. Alfred J. Beck and his wife, Annie. Dr. Beck, a pharmacist, came to Fort Lauderdale in 1915 and opened one of the first drug stores in town. In 1916, Dr. Beck married Annie Margaret Atkinson and together they built this house which was to remain as Annie’s home until she died in 1985. Annie Beck was heavily involved with organizations in the community. -

Broward County Pioneer Day 2019

BRf#{'i~ MMM•MiMM•M·i - B ~ ARD p mpano B~~ ARD COUNTY ':OUNT1 FLORIDA •HSTORIC PRESERVATION BOARD • beach ~Dw~ Fl o' ida 's Wa rmest Vle, lr,0m<; to the men and women who have been selected as Broward County Pioneers! FROMTHE BROWARD COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS District I District 4 District 7 Nan H. Rich Lamar P. Fisher Tim Ryan District 2 District 5 District 8 Mark D. Bogen Steve Geller Dr. Barbara Sharief Mayor District 6 District 9 District 3 Beam Furr Dale V.C. Holness Michael Udine Vice-Mayor m COUNTY FLORIDA Broward County Historic Preservation Board presents the 45th Annual Pioneer Day Celebration Saturday, May 11th Pompano Beach Cultural Center ~·, BPtW ARD p mpano BR-~ ARD COUNTY COUNTY FLORIDA HISTORIC PRESERVATION BOARD • beach~ Florida's Warmest Welcome ~~~ Broward.org/History Welcome to the 45th Annual Pioneer Day! This year we are lucky to be hosted in the City of Pompano Beach at the beautiful Pompano Beach Cultural Center. Pioneers are defined by their inventive spirit and their willingness to take risks. They can see beyond the world as it is to the world as it should be. The spirit of the pioneer is alive and well in Broward County, and it is a great service to be able to honor those individuals today. Congratulations to the men and women who have been selected as Broward County pioneers. They join a group of over 1,500 individuals that the Commission has honored over the past decades. Your contributions have helped build Broward County into what it is today and have laid a strong foundation for what it will become. -

Executive Summary Davie Elementary School

Executive Summary Davie Elementary School Broward County Public Schools Mr. Robert N Schneider 7025 S.W. 39th Street Davie, FL 33314 Document Generated On November 13, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Description of the School 2 School's Purpose 3 Notable Achievements and Areas of Improvement 4 Additional Information 6 Executive Summary Davie Elementary School Introduction Every school has its own story to tell. The context in which teaching and learning takes place influences the processes and procedures by which the school makes decisions around curriculum, instruction, and assessment. The context also impacts the way a school stays faithful to its vision. Many factors contribute to the overall narrative such as an identification of stakeholders, a description of stakeholder engagement, the trends and issues affecting the school, and the kinds of programs and services that a school implements to support student learning. The purpose of the Executive Summary (ES) is to provide a school with an opportunity to describe in narrative form the strengths and challenges it encounters. By doing so, the public and members of the school community will have a more complete picture of how the school perceives itself and the process of self-reflection for continuous improvement. This summary is structured for the school to reflect on how it provides teaching and learning on a day to day basis. Page 1© 2017 Advance Education, Inc. All rights reserved unless otherwise granted by written agreement. Executive Summary Davie Elementary School Description of the School Describe the school's size, community/communities, location, and changes it has experienced in the last three years. -

Executive Summary Davie Elementary School

Executive Summary Davie Elementary School Broward County Public Schools Mr. Erik Anderson 7025 S.W. 39th Street Davie, FL 33314 Document Generated On November 13, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Description of the School 2 School's Purpose 3 Notable Achievements and Areas of Improvement 4 Additional Information 6 Executive Summary Davie Elementary School Introduction Every school has its own story to tell. The context in which teaching and learning takes place influences the processes and procedures by which the school makes decisions around curriculum, instruction, and assessment. The context also impacts the way a school stays faithful to its vision. Many factors contribute to the overall narrative such as an identification of stakeholders, a description of stakeholder engagement, the trends and issues affecting the school, and the kinds of programs and services that a school implements to support student learning. The purpose of the Executive Summary (ES) is to provide a school with an opportunity to describe in narrative form the strengths and challenges it encounters. By doing so, the public and members of the school community will have a more complete picture of how the school perceives itself and the process of self-reflection for continuous improvement. This summary is structured for the school to reflect on how it provides teaching and learning on a day to day basis. Page 1© 2017 Advance Education, Inc. All rights reserved unless otherwise granted by written agreement. Executive Summary Davie Elementary School Description of the School Describe the school's size, community/communities, location, and changes it has experienced in the last three years. -

Vol16 Issue 2 Davieupdatetext

SUMMER 2019 | VOL. 16 | ISSUE 2 DAVIE UPDATE THE TOWN OF DAVIE’S OFFICIAL NEWS MAGAZINE CENSUS 101: WHY 2020 MATTERS REASONS TO COMPLETE THE FORM SUNRISE UTILITIES INFORMATION:QUESTIONS & ANSWERS HURRICANE PREPAREDNESS:HOW TO KEEP YOUR FAMILY SAFE Page 2 FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL:@TownofDavie TOWN ADMINISTRATION Town Administrator Richard J. Lemack Deputy Town Administrator Macciano K. Lewis Assistant Town Administrator Phillip R. Holste ___________ EDITORS Managing Editor Public Relations Coordinator Leona Henry 954-797-1035 [email protected] Design Editor Public Relations Assistant Sussette Rodriguez 954-797-1102 [email protected] 2019 TOWN COUNCIL AND CRA MEETINGS CRA July 31, 2019 6:00 p.m. Council July 31, 2019 6:30 p.m. CRA August 7, 2019 6:00 p.m. Council August 7, 2019 6:30 p.m. CRA August 21 2019 6:00 p.m. Council August 21 2019 6:30 p.m. CRA September 5, 2019 6:00 p.m. Council September 5, 2019 6:30 p.m. Council September 18, 2019 6:30 p.m. CRA October 2, 2019 6:00 p.m. Council October 2, 2019 6:30 p.m. *Dates and times subject to change* Please visit www.davie-fl.gov for the latest meeting information. DAVIE UPDATE Page 3 IN THIS ISSUE Page 4 Message from the Mayor Page 5 Thoughts and Comments From the Davie Town Council Page 6 Community Endowment Fund Page 7 HHW & Electronics Recycling Page 8 Hurricane Preparedness Tips Page 9 Town Information Page 10 Flood Hazard Information Page 12 Town Events Page 13 Parks, Recreation & Cultural Arts Page 19 Census 101 Page 20 Police Updates Page 21 Fire Updates Page 23 Sunrise Utilities FAQs TOWN COUNCIL Picture of Davie Town Council on the right 1 Mayor Judy Paul 2 Vice Mayor Caryl Hattan (District 2) 3 Councilmember Bryan Caletka (District 1) 4 Councilmember Susan Starkey (District 3) 5 Councilmember Marlon Luis (District 4) THE DAVIE UPDATE: The Davie Update is the official publication of the Town of Davie. -

Volume 13, Issue 3, October 2016

DAVIE UPDATE Fall 2016 Vol. 13, Issue 3 The Town of Davie’s Official News Magazine THE DAVIE UPDATE The Davie Update is the official publication of the Town of Davie. The magazine is published three In this times per year and is mailed to Issue residents within the Town under Fall 2016 Vol. 13, Issue 3 the direction of the Administration Department. The Davie Update also can be viewed on the web at 3 Mayor’s Message 10 Out & About www.davie-fl.gov. 4 Town Council Thoughts & Comments 12 Police & Fire Rescue The Town of Davie strives to be the preeminent community in 5 The mural titled Run 14 In the Holiday Spirit South Florida to live, work, learn, and play while treasuring our 6 A Penny at Work 15 Parks, Recreation & Cultural Arts preserved natural setting. 8 PACE Broward 22 Bergeron Rodeo Grounds 9 Calling all Baby Boomers 23 Old Davie School/Young at Art Town Council Mayor Judy Paul District 1 Councilmember Bryan Caletka District 2 Councilmember Caryl Hattan Upcoming Town Council District 3 Meetings Councilmember Susan Starkey District 4 Vice Mayor Marlon Luis 11/02/16 Wed. 6:30 P.M. Administration Town Administrator 12/07/16 Wed 6:30 P.M. Richard J. Lemack 01/04/17 Wed. 6:30 P.M. Deputy Town Administrator Macciano K. Lewis 01/18/17 Wed. 6:30 P.M. Assistant Town Administrator Phillip R. Holste Editor Public Relations Coordinator Advisory Committees & Other Meetings Anita Reid The Town has a number of advisory boards and committees that provide recommendations to 954-797-1102 the Town Council regarding special program areas. -

BCC Executive Council

Cultural Division 100 S. Andrews Avenue • Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33301 • 954-357-7457 • FAX 954-357-5769 DATE: July 9, 2020 TO: BROWARD CULTURAL COUNCIL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING FROM: Phillip Dunlap, Director SUBJECT: MEETING NOTIFICATION Thursday, July 16, 2020, 12:00pm WebEx Virtual Meeting Conference Call Number: 408-418-9388 If you haven’t already done so, RSVP to notify if you plan to attend the meeting by calling Ava Stringfellow at 954-357-7308 or accessing the doodle link: https://doodle.com/poll/ndpd9wkhk67c858v Cultural Division invites you to join this Webex meeting. Meeting number (access code): 126 172 6237 Meeting password: Executive (39328848) Distribution: EC: Broward Cultural Council Kimm Campbell, Acting Assistant Administrator Arlene Jardine, County Administration Specialist Cultural Division Staff - Andy Royston (for web posting) Broward County Board of County Commissioners Mark D. Bogen • Lamar P. Fisher • Beam Furr • Steve Geller • Dale V.C. Holness • Nan H. Rich • Tim Ryan • Barbara Sharief • Michael Udine www.broward.org BROWARD CULTURAL COUNCIL Executive Committee Meeting Thursday, July 16, 2020 - 12:00 PM WebEx Conference Meeting AGENDA I. Call to Order and Roll Call Gregory Reed, Chair Ava Stringfellow, Administrative Assistant II. Approval of meeting minutes of April 16, 2020 (Exhibit 1, pages 1 - 4) Ill. Action Agenda GRANTS 1. MOTION TO RECOMMEND approval of the peer review panel's recommendations for the Cultural Investment Program (CINV) from the April 22, 2020 panel review meeting for FY 2021. Funding recommendations for awardees will commence October 1, 2020, for FY 2021, with later adjustments to funding awards to be made based on approval of the FY 2021 incentive (grant) budget. -

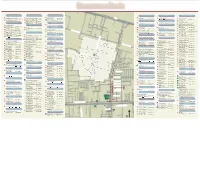

Davie Road Establishment Map (PDF)

Downtown Davie ACCOUNTANTS CONTRACTORS ELECTRICAL HOTELS / LODGING PRINTING SPECIALTY STORES 97 36 107 Davie Electric Service 76 35 43 Goode, Medvin & Weissman, LLC Clearview Cleaning Contractors I5I59 Comfort Suites State-Wide Printing . 4144 Davie Road (954) 583-3901 5 Army Navy Outdoors 6330 SW 41st Court (954) 581-0801 6440 SW 42nd Street (954) 452-0003 2540 Davie Road (954) 585-7071 4166 Davie Road (954) 791-8447 4130 Davie Road (954) 584-7227 104 1 4 Bel-Tec Electrical Services Inc. 17 Santini & Associates, CPA., P.A. James B. Pirtle Construction Inc. ICE CREAM SHOP PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 4468 Davie Road 4740 Davie Road (954) 797-0410 16 118 Circle K T.V. Repair Shop Megan South General Contractors ELECTRONICS 88 ATTORNEYS Dairy Queen Downtown Davie (Proposed Development) 4470 Davie Road (954) 584-0097 6521 Orange Drive (954) 316-7000 6552 SW 39th Street (954) 584-4081 111 30 Credit Restoration Consolidation, Inc. 132 PUBLIC PARKING LOT Bonne Z. Scheflin, P.A CONVENIENCE STORES Sonic Boom Mobile Electronics & Beepers INSURANCE 4263 Davie Road Ste. 2 (954) 581-5050 4699 Davie Road (954) 443-8580 4232 Davie Road (954) 791-1491 23 Datel Corp 68 93 FARM SUPPLIES 15 P Douglas P. Johnson & Associates Farm Store 4274 Davie Road (954) 797-0329 A Able Insurance Public Parking 2924 Davie Road (954) 522-0223 6516 SW 39th Street (954) 791-1397 73 7 4480 Davie Road (954) 791-7116 4166 South West 63 Avenue Florida Radio Rental, Inc. 114 127 114 Henderson & Kisslan Attorney At Law Super Stop Grifs Feed & Pet Supply N 78 Allstate Insurance Company 2700 Davie Road (954) 581-4437 O REAL ESTATE 4431 Davie Road, Ste.