Ink Knows No Borders • a Teaching Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Borders by Consent

Borders by Consent: A Proposal for Reducing Two Kinds of Violence in Immigration Practice Richard Delgado* Jean Stefancic** ABSTRACT We describe a new consensual theory of borders and immigration that reverses Peter Schuck’s and Rogers Smith’s notion of citizenship by consent and posits that borders are legitimate—and make sense—only if they are products of consent on the part of both countries on opposite sides of them. Our approach, in turn, leads to differential borders that address the many sovereignty and federalist problems inherent in border design by a close examination of the policies that different borders—for example, the one between California and Mexico—need to serve in light of the populations living nearby. We build on our work on border laws as examples of Jacques Derrida’s originary violence. We assert that laws that exhibit a high degree of originary violence lead, almost ineluctably, to actual violence and cruelty, such as that perpetrated by Donald Trump’s child-separation policy, and that consensual and relatively open borders are the most promising way to minimize both forms of violence, originary and actual. 338 ARIZONA STATE LAW JOURNAL [Ariz. St. L.J. INTRODUCTION Suppose that the underlying basis for a significant area of social regulation fails badly when viewed from the perspective of any of the leading theories of human organization and only holds appeal to those who are indifferent about perpetrating pain and hardship on fellow humans and need a plausible justification for doing so—namely that “they broke the law.”1 Consider current U.S. -

Thesis Final Draftx

ANTECEDENTS AND ADAPTATIONS IN THE BORDERLANDS: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF INFORMAL SOCIO-ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES ACROSS THE RHODESIA-MOZAMBIQUE BORDER WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE CITY OF UMTALI, 1900-1974 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Humanities of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Supervisor: Dr. Muchaparara Musemwa Fidelis Peter Thomas Duri University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa 2012 i CONTENTS Declaration ...................................................................................................................................... i Abstract ............................................................................................................................ ………..ii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iii List of acronyms ........................................................................................................................... iv Glossary of terms ...........................................................................................................................v List of illustrations ..................................................................................................................... viii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background ..............................................................................................................................1 -

MUSIC TRADE MAGAZINE KAY KNIGHT Nashville Editor Editorial KAREN WOODS, Assoc

MAGAZINE TRADE MUSIC THE 9 STAFF BOX GEORGE ALBERT President and Polisher ROBERT LONG VOL Ull, NO. #6, JUNE 23, 1990 Vice PresidentAJrban Marketing KEITH ALBERT Vice President/General Manager JIM SHARP Director, Nashville Operations PASIG CAMILLE COM j Director, Coin Machine Operations Marketing JIM WARSINSKE (LA.) MIKE GORDON (LA ) KEITH GORMAN Editor LEEJESKE BOX New York Editor THE MUSIC TRADE MAGAZINE KAY KNIGHT Nashville Editor Editorial KAREN WOODS, Assoc. Ed. (N. Y.j 8 KIMMY WIX, Assoc. Ed. (Nash.) ERNEST HARDY, Assoc. Ed. (LA) TONYSABOURNIN, Assoc. Ed., Latin (N. Y.) SHELLY WEISS, Assoc. Ed., Publishing (LA.) BERNETTA GREEN (NX) CONTENTS WILMA MELTON (Nash.) ALEX HENDERSON (LA.) 8 MUSIC PUBLISHING 1990 SPECIAL ISSUE Chart Research Interviews with26the movers and shakers of the publishing industry, and more, so much more. SCOTT M. SALISBURY 27 BY SHELLY WEISS Coordinator (LA.) 28 JOHN DECKER (Nash.) 30 C J. (War Flower)(LAJ 31 TERESA CHANCE (Nash.) 32 COLUMNS JEFF KARP (LA.) NATHAN W.(DXF) HOLSEY (LA.) 4 East Coasting / To long-box or not to long-box, that is the question, and Karen Woods has the answer. Production 4 London Calling / Chrissy Iley, Dusty Springfield and a whole shirtload of cats, plus a catty comment about the JIM GONZALEZ Beach Ball. Art Director 5 Faces On Top, by Ernest Hardy; Child's Play, by Alex Henderson; Doug Stone, by Kay Knight. Circulation New / NINATREGUB, Manager 6 Retail News / Retail for the visually impaired, by C.J. and Jeff Karp. CYNTHIA BANTA ; 7 Indie Focus / Hey, chief, that's indie, not in die, with Alex Henderson. -

Hugh Masekela: the Long Journey 1959-1968

HUGH MASEKELA: THE LONG JOURNEY 1959-1968 By RICARDO CUEVA A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research written under the direction of Dr. Henry Martin and approved by ___________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2020 © 2020 Ricardo Cueva ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Abstract of the Thesis Hugh Masekela: The Long Journey By Ricardo Cueva Thesis Director: Henry Martin This thesis chronicles Masekela's transition from African refugee to Grammy nominated artist while also encompassing a musical analysis of his work before and including The Promise of the Future. This thesis will provide brief biographical information of Masekela’s life as well as a sociological analysis to give context to his place in US pop culture. This study discusses Masekela’s upbringing in South Africa and explores his transition into 1960s America. This thesis argues that Masekela faced an authenticity complex when breaking into the US market because he defied the expectations of what US audiences thought Africans to be. Masekela overcame this obstacle with the release of The Americanization of Ooga Booga (1966). A musical analysis and critique of the first three albums with an emphasis on Masekela’s breakthrough compositions will be part of this thesis. This thesis concludes with a brief analysis of the cultural and racial impact of Masekela’s work both in the United States and South Africa. ii Acknowledgements I would first and foremost like to thank my parents for their constant support and sacrifice. -

Songs with a Global Conscience Using Songs to Build International Understanding and Solidarity

The New Teacher Book - Rethinking Schools Online Page 1 of 7 Songs with a Global Conscience Using Songs to Build International Understanding and Solidarity The songs below are divided into the following categories: The Colonial Past Current North/South Global Realities Global Sweatshops Food and Agriculture Globalization on the Homefront Culture, Power and Environment Teaching and Organizing for Justice By Bob Peterson Songs, like poetry, are powerful tools to build consciousness and solidarity on global issues. We begin everyday in my classroom with our "song of the week." Students receive the song lyrics and keep them in their three-ring binders. The songs generally relate to topics of study. I allow students to bring in songs as well, although they must know the lyrics and have a reason for sharing the song with classmates. By the end of the week, students may not have memorized the words to the "song of the week," but they are familiar enough with the lyrics and music so that the song becomes "theirs." Even with some of the songs that I would imagine the children think poorly of — say, some of the slower folk songs — by the end of the week the children demand to hear them a second or third time each morning. When I introduce a song, I go over the geographical connections using a classroom map. I also explain any vocabulary words that might be difficult. Finally, and most importantly, I give the social context. Depending on whether I use the song at the beginning of a unit of study, or in the middle, the amount of "context setting" varies greatly. -

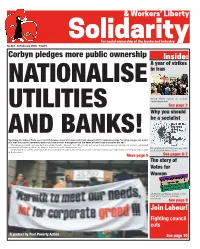

Corbyn Pledges More Public Ownership Inside: a Year of Strikes NATIONALISE in Iran

& Workers’ Liberty SolFor siociadl ownershaip of the branks aind intdustry y No 462 14 February 2018 50p/£1 Corbyn pledges more public ownership Inside: A year of strikes NATIONALISE in Iran Morad Shirin reports on workers organising in Iran. See page 3 UTILITIES Why you should be a socialist ASpeaking at a LNabour Party evDent on 10 Febru ary, JeBremy Corbyn rAeaffirmed LabNour’s 2017 manKifesto pledge “Sto bring energ! y, rail, water, and mail into public ownership and to put democratic management at the heart of how those industries are run”. “By taking our public services back into public hands”, he said, “we will not only put a stop to rip-off monopoly pricing, we will put our shared values and collective goals at the heart of how those public services are run”. We publish an extract from our new He promised “a society which puts its most valuable resources, the creations of our collective endeavour, in the hands of everyone who is part book, Socialism Makes Sense of that society”. More page 5 See pages 6-7 The story of Votes for Women Jill Mountford begins a series on the story of the women’s suffrage movement. See page 9 Join Labour! Fighting council cuts A protest by Fuel Poverty Action See page 10 2 NEWS More online at www.workersliberty.org Share-price wobble gives warning By Rhodri Evans lower than their recent highs on 29 higher than the average over the But wobbles can turn into selling shares again at a higher January, 23 January, and 26 January last 14 years, which is 12.6. -

Richard Butz)»

Hör- und Lese-Tipps zum Beitrag «Blick auf den südafrikanischen Jazz. Eine langjährige Beziehungsgeschichte (Richard Butz)» CDs und LPs: Jazz and Hot Dance in South Africa 1946-1959 (LP, Harlequin Records, 1985) South African Hip Kings, Hip Queens and The New Jazz Pioneers (The Rough Guide, World Music Network, 2000) Live at the Birds Eye Jazz Club: Volume 13: South Africa (the bird’s eye jazz club, 2013) Hugh Masekela: Home Is Where the Music Is (Verve, 1978 / No Borders [Masekelas letztes Album] (Universal Music, 2016) Miriam Makeba: Homeland (Putumayo Records, 2000) / The Guinea Years (Sterns Music, 2001) Abdullah Ibrahim a.k.a. Dollar Brand: Duke Ellington Presents the Dollar Brand Trio (Reprise, 1964) / Anatomy of a South African Village, 1965 (Da Music, Jazz Colours, 1999) / mit Johnny Dyani: Good News from Africa, 1973 (Enja, 2007 & 2016) Sathima Bea Benjamin with Dollar Brand: African Songbird, 1976 (Matsuli Records, 2013) Irène Schweizer – Louis Moholo [1987] (Intakt Records, 1996) Chris McGregor Group: Township Bebop [1964] (Proper Records, 2002) / Originalformation mit Ronnie Beer, Tenorsaxofon: Very Urgent [1968] (Fledg’ling Records, 2008) / The Brotherhood of Breath: Live at Willisau [1973] (Ogun, 2016) Joe Malinga: Ithi Gqi (Brambus Records, 1990) Carlo Mombelli: Live at the Birds Eye 2009-2018 (Mombelli Music, 2019) Kesivan Naidoo mit Lucas Niggli Drum Quartet: Beat Bag Bohemia (Intakt, 2008) / Kesivan & The Lights: Brotherhood (Sony, 2014) Makaya Ntshoko & the New Tsotsis: Happy House (Steeplechase, 2008) / mit Omri Ziegele’s Where’s Africa Trio (mit Irène Schweizer): Can Walk on Sand (Intakt, 2010) Bänz Oester & The Rainmakers: Playing at The Birds Eye (Unit/Werkstatt Records, 2014) / Ukuzinikela Live in Willisau (Enja, 2015) Skyjack: Skyjack (Werkstatt Record, 2016) / The Hunter (Enja, 2019) Dominic Egli’s Plurism feat. -

Religion, Culture, and Society: the Case of Cuba

libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page i RELIGION, CULTURE, AND SOCIETY: THE CASE OF CUBA Woodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas • # 9 libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page ii Printed in Argentina Designed milstein)ravel www.milsteinravel.com.ar ©2003 Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, D.C. www.wilsoncenter.org libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page iii RELIGION, CULTURE, AND SOCIETY: THE CASE OF CUBA W oodrow Wilson Center Reports on the Americas • # 9 A Conference Report Conference Organizer & Editor Margaret E. Crahan with the assistance of Elizabeth Bryan Mauricio Claudio & Andrew Stevenson Latin American Program libro_Cuba_ok 1/12/03 6:09 PM Page iv THE WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Director BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joseph B. Gildenhorn, Chair; David A. Metzner, Vice Chair. Public Members: James H. Billington, Librarian of Congress; John W. Carlin, Archivist of the United States; Bruce Cole, Chair, National Endowment for the Humanities; Roderick R. Paige, Secretary, U.S. Department of Education; Colin L. Powell, Secretary, U.S. Department of State; Lawrence M. Small, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution; Tommy G. Thompson, Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Private Citizen Members: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., Carol Cartwright, Donald E. Garcia, Bruce S. Gelb, Daniel L. Lamaute, Tamala L. Longaberger, Thomas R. Reedy WILSON COUNCIL Bruce S. Gelb, President. Diane Aboulafia-D'Jaen, Elias F. Aburdene, Charles S. Ackerman, B.B. Andersen, Cyrus A. Ansary, Lawrence E. Bathgate II, John Beinecke, Joseph C. Bell, Steven Alan Bennett, Rudy Boschwitz, A. Oakley Brooks, Melva Bucksbaum, Charles W. -

ACHIEVING U.S. SECURITY THROUGH LEADERSHIP & LIBERTY June 9, 2016 Better.Gop

ACHIEVING U.S. SECURITY THROUGH LEADERSHIP & LIBERTY June 9, 2016 better.gop A BETTER WAY | 1 Report of the Task Force on National Security Table of Contents The Responsibility of Congress .............................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Keeping Americans safe at home ............................................................................................................ 4 Keep terrorists out of America and confront homegrown threats ............................................................... 4 Secure the border and enforce our immigration laws .............................................................................. 5 Enhance our cyber defenses ............................................................................................................... 6 Defeating Terrorists ............................................................................................................................. 8 Take the fight to the enemy ............................................................................................................... 8 Win the battle of ideas .................................................................................................................... 10 Defending Freedom and Advancing American Interests ............................................................................ -

Internationally Acclaimed Pianist, Composer & Humanitarian Keiko

Internationally Acclaimed Pianist, Composer & Humanitarian Keiko Matsui Creates Enchanting Global Sonic Tapestry On New Shanachie Recording Echo New CD Unites Matsui with All-Star Line Up Including Gretchen Parlato, Marcus Miller, Kirk Whalum, Robben Ford & Kyle Eastwood “There is a strong spiritual quality Keiko Matsui brings to all of her creative projects.”- The Los Angeles Times "Keiko Matsui is appreciated not just as an artist but as a humanitarian. She dedicates every song she writes to causes that move her..."-NPR “…Pretty melodies and spiritually uplifting anthems.”- JazzTimes Magazine Acclaimed pianist, composer and humanitarian Keiko Matsui's transcendent and haunting melodies have long sought to build bridges. Her sonic cultural exchange has reached the hearts and minds of fans throughout the world and has allowed the pianist to work alongside icons Miles Davis, Stevie Wonder, Hugh Masekela and Bob James. “I would like my music to be a conduit for peace, kindness, love and light,” shares the petite, soft- spoken, yet commanding pianist. She adds, “My recording Echo is my attempt to capture all of these elements into the vibration of sound.” On February 22, 2019 Keiko Matsui will release her 28th recording as leader, Echo, which she co-produced with Grammy nominated producer Bud Harner. A master storyteller, Matsui crafts exquisite compositions replete with lush harmonies and global rhythms to create timeless musical anthems. Like iconic musicians Miles Davis and Shirley Horn, Keiko is also a master at utilizing space in her music to create a backdrop of drama, tension and sheer beauty. Keiko’s most inspired work yet, Echo features numerous special guests including bassist Marcus Miller, saxophonist Kirk Whalum, vocalist Gretchen Parlato, guitarist Robben Ford and bassist (and son of Clint Eastwood) Kyle Eastwood. -

Ethno-Techno: Writings on Performance, Activism, and Pedagogy

ethno-techno The performance of “extreme identity” is familiar to us all through the medium of television (just switch on Jerry Springer). So where does this leave the critical practice of artists who aim to make tactical, performative interventions into our notions of race, culture, and sexuality? Guillermo Gómez-Peña has spent many years developing his unique style of performance-activism: his theatricalizations of postcolonial theory. In Ethno-Techno: Writings on performance, activism, and pedagogy, he pushes the boundaries still further, exploring what’s left for artists to do in a post-9/11 repressive culture of what he calls “the mainstream bizarre”. Extensive photos document his artistic experiments. The text not only explores and confronts his political and philosophical parameters, it offers an insight into one of the most daring, innovative, and challenging performance artists of our age. Guillermo Gómez-Peña is a performance artist and writer, and Artistic Director of San Francisco-based company La Pocha Nostra. His pioneering work in per- formance, video, radio, installation, poetry, journalism, and cultural theory explores crosscultural issues, immigration, the side effects of globalization, the politics of language, “extreme culture,” and the digital divide. His previous books include Warrior for Gringostroika (1993), The New World Border (1996), and Dangerous Border Crossers (2000). ethno-techno Writings on performance, activism, and pedagogy by Guillermo Gómez-Peña edited by Elaine Peña L ˙ L ` ˙ L ` ˙ First published 2005 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Björk Reaches Beyond the Binaries

COMMUNICATOR BETWEEN WORLDS: BJÖRK REACHES BEYOND THE BINARIES Edwin F. Faulhaber A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2008 Committee: Kimberly Coates, Advisor Robert Sloane ii ABSTRACT Kimberly Coates, Advisor Icelandic pop star Björk has spent her career breaking down boundaries, blurring lines, and complicating binaries between perceived opposites. Examining a variety of both primary and secondary sources, this study looks at the ways that Björk challenges the binary constructions of “high” and “low” art, nature and technology, and feminism and traditional femininity, and also proposes that her uniquely postmodern approach to blurring boundaries can be a model for a better society in general. This study contends that Björk serves as a symbol of what might be possible if humans stopped constructing boundaries between everything from musical styles to national borders, and as a model for how people can focus on their commonalities while still respecting the freedom of individual expression. This is particularly important in the United States of America, a place where despite its infinite potential for cultural pluralism and collaboration, there are as many (or more) divisions between people based upon race, class, gender, and religion as anywhere else in the world. iii Dedicated to Morgaine iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Kim Coates and Rob Sloane, for all of their suggestions and encouragement while I wrote this thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Don McQuarie and Gloria Enriquez Pizana for their support and assistance, as well as a host of wonderful professors who laid the groundwork for this thesis by inspiring me along the way: Rob, Kim, Drs.