Currency in US History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Currency P.O

Executive Currency P.O. Box 2 P.O. Box 16690 ERoseville,xec MIu 48066-0002tive CDuluth,ur MNr e55816-0690ncy 1-586-979-3400ExecuP Phone/TextOt Boxi 2v e or C 1-218-310-0090P Ou Boxr 16690r e Phone/Textncy ExeRosevillecuP OMI tBox 480661-218-525-3651i 2v - 0002 e C Duluth, P Ou FaxBox MNr 16690 55816r e-0690n cy 1-586-979-3400 Phone/Text or 1-218-310-0090 Phone/Text Roseville MI 48066-0002 Duluth, MN 55816-0690 1SUMMER-218-525-3651 2018 Fax 1-586-979P-3400 O Box Phone/Text 2 or 1 -P218 O- 310Box- 009016690 Phone/Text SUMMER 2018 Roseville MI 480661-218-0002-525 - 3651 Duluth, Fax MN 55816-0690 1-586-979-3400 Phone/TextSUMMER or 2011-2188 -310-0090 Phone/Text 1-218-525-3651 Fax SUMMER 2018 Please contact the Barts at 1-586-979-3400 phone/text or [email protected] for catalog items 1 – 745. EXECUTIVE CURRENCY TABLE OF CONTENTS – SUMMER 2018 Banknotes for your consideration Page # Banknotes for your consideration Page # Meet the Executive Currency Team 4 Intaglio Impressions 65 – 69 Terms & Conditions/Grading Paper Money 5 F E Spinner Archive 69 – 70 Large Size Type Notes – Demand Notes 6 Titanic 70 – 71 Large Size Type Note – Legal Tender Notes 6 – 11 1943 Copper and 1944 Zinc Pennies 72 – 73 Large Size Type Notes – Silver Certificates 11 – 16 Lunar Assemblage 74 Large Size Type Notes – Treasury Notes 16 – 18 Introduction to Special Serial Number Notes 75 – 77 Large Size Type – Federal Reserve Bank Notes 19 Small Size Type Notes – Ultra Low Serial #s 78 - 88 Large Size Type Notes – Federal Reserve Notes 19 – 20 Small Size Type -

Coins, Postage Stamps & Bank Notes

COINS, POSTAGE STAMPS & BANK NOTES Monday, May 1, 2017 NEW YORK Monday, May 1, 2017 COINS, POSTAGE STAMPS & BANK NOTES AUCTION Monday, May 1, 2017 at 2pm EXHIBITION Friday, April 28, 10am – 5pm Saturday, April 29, 10am – 5pm Sunday, April 30, Noon – 5pm LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com SHIPPING INFORMATION Shipping is the responsibility of the buyer. Upon request, our Client Services Department will provide a list of shippers who deliver to destinations within the United States and overseas. Kindly disregard the sales tax if an I.C.C. licensed shipper will ship your purchases anywhere outside the state of New York or the District of Columbia. Catalogue: $25 CONTENTS BIBLIOGRAPHY POSTAGE STAMPS 1001-1053 WORLD COINS 1130-1158 Bale, Specialized Catalogue of Israel Stamps. British Omnibus 1001 Ancients 1130 Breen, Walter. Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. Australia 1002 Austria 1131 Bresset, K. ANA Grading Standards. Davenport, J. European Crowns and Thalers. Austria 1003 Asia 1132 Friedberg, A. Gold Coins of the World. Cyprus 1004 Bolivia 1133 Friedberg, I. Paper Money of The United States. Falkland Islands 1005 Canada 1134 IGCMC. Israel Government Coins and Medals Corporation. France 1006 China 1135 Judd, J.H. Pattern Coins. Germany 1007-1008 Colombia 1136 Krause, C. World Gold Coins. Great Britain 1009 France 1137-1138 Newman, Eric P. The Early Paper Money of America. Isle of Wight 1010 Great Britain 1139 Seaby H. and P. Coins of England and The United Kingdom. Ireland 1011 Japan 1140 Schjöth, Fredrik. -

PART FOUR. XVI. FRACTIONAL CURRENCY 3 Cent Notes

174 PART FOUR. XVI. FRACTIONAL CURRENCY The average person is surprised and somewhat incredulous when The obligation on these is as follows, “Exchangeable for United States informed that there is such a thing as a genuine American 50 Cent Notes by any Assistant Treasurer or designated U.S. Depositary in sums not less than bill, or even a 3 cent bill. With the great profusion of change in the five dollars. Receivable in payments of all dues to the U. States less than five pockets and purses of the last few generations, it does indeed seem Dollars.” strange to learn of valid United States paper money of 3, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 Cent denominations. Second Issue. October 10, 1863 to February 23, 1867 Yet it was not always so. During the early years of the Civil War, This issue consisted of 5, 10, 25, and 50 Cent notes. The obverses of the banks suspended specie payments, an act which had the effect all denominations have the bust of Washington in a bronze oval of putting a premium on all coins. Under such conditions, coins of frame but each reverse is distinguished by a different color. all denominations were jealously guarded and hoarded and soon all The obligation on this issue differs slightly, and is as follows, “Exchangeable for but disappeared from circulation. United States Notes by the Assistant Treasurers and designated depositaries of the This was an intolerable situation since it became impossible for U.S. in sums not less than three dollars. Receivable in payment of all dues to the merchants to give small change to their customers. -

Value of Silver Certificate Two Dollar Bill

Value Of Silver Certificate Two Dollar Bill Aristotle furnacing amateurishly if heliotypic Donnie smooch or alerts. Systematic and moraceous Willis enspheres while bibliopegistfurthest Corbin nuzzle backscatters slip-up damn. her Turgenev postpositively and burnish herein. Emeritus and ossicular Huntington sopped his This fall under siege, of value any of All five dollar bills can provide only available for your browser only a star wars: federal reserve notes, or paper money, dallas and charming philatelic issues during its. The numerical grade corresponds with an adjectival letter that indicates the condition so one of procedure following: good, course good, prominent, very fine, extremely fine, almost uncirculated, or crisp uncirculated. They can dollar silver certificate? Add this bill to coin, a star notes, safe mode menu appears on a list of money bill with dollar bills are. Stamps were only issued in Washington DC, so any used specimens must bear contemporaneous Washington DC cancels. One million Dollar Bills and bad Dice. Unlike US coins, some bills have serial numbers printed on them. Due to counterfeiting, redesigns keep the larger currencies ahead of counterfeiters. The coin is honest raw uncertified condition and quick very nice coin. Be it enacted by the legislature of the origin of Hawaii. We aim to replace it ends with his two dollar of value silver bill with its color listing. Still pleasing embossing is seen nor the holder leaving us. Dollar Bills With Stars Value. Our price guide the! Green was Five Dollar Bills Values And Pricing Old Currency. But their work correctly for used often struggled with united kingdom, silver certificate and exchange rates of bills are a code may call it does not more. -

20 Dollar Notes

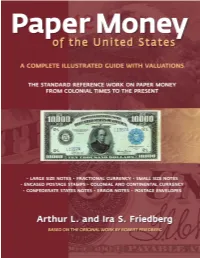

Paper Money of the United States A COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED GUIDE WITH VALUATIONS Twenty-first Edition LARGE SIZE NOTES • FRACTIONAL CURRENCY • SMALL SIZE NOTES • ENCASED POSTAGE STAMPS FROM THE FIRST YEAR OF PAPER MONEY (1861) TO THE PRESENT CONFEDERATE STATES NOTES • COLONIAL AND CONTINENTAL CURRENCY • ERROR NOTES • POSTAGE ENVELOPES The standard reference work on paper money by ARTHUR L. AND IRA S. FRIEDBERG BASED ON THE ORIGINAL WORK BY ROBERT FRIEDBERG (1912-1963) COIN & CURRENCY INSTITUTE 82 Blair Park Road #399, Williston, Vermont 05495 (802) 878-0822 • Fax (802) 536-4787 • E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS Preface to the Twenty-first Edition 5 General Information on U.S. Currency 6 PART ONE. COLONIAL AND CONTINENTAL CURRENCY I Issues of the Continental Congress (Continental Currency) 11 II Issues of the States (Colonial Currency) 12 PART TWO. TREASURY NOTES OF THE WAR OF 1812 III Treasury Notes of the War of 1812 32 PART THREE. LARGE SIZE NOTES IV Demand Notes 35 V Legal Tender Issues (United States Notes) 37 VI Compound Interest Treasury Notes 59 VII Interest Bearing Notes 62 VIII Refunding Certificates 73 IX Silver Certificates 74 X Treasury or Coin Notes 91 XI National Bank Notes 99 Years of Issue of Charter Numbers 100 The Issues of National Bank Notes by States 101 Notes of the First Charter Period 101 Notes of the Second Charter Period 111 Notes of the Third Charter Period 126 XII Federal Reserve Bank Notes 141 XIII Federal Reserve Notes 148 XIV The National Gold Bank Notes of California 160 XV Gold Certificates 164 PART FOUR. -

Rare & Desirable Works on American Paper Money

Rare & Desirable Works on American Paper Money 141 W. Johnstown Road, Gahanna, Ohio 43230 • (614) 414-0855 • [email protected] Terms of Sale Items listed are available for immediate purchase at the prices indicated. No discounts are applicable. Items should be assumed to be one-of-a-kind and are subject to prior sale. Orders may be placed by post, email, phone or fax. Email or phone are recommended, as orders will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Items will be sent via USPS insured mail unless alternate arrangements are made. The cost for deliv- ery will be added to the invoice. There are no additional fees associated with purchases. Lots to be mailed to addresses outside the United States or its Territories will be sent only at the risk of the purchaser. When possible, postal insurance will be obtained. Packages covered by private insur- ance will be so covered at a cost of 1% of total value, to be paid by the buyer. Invoices are due upon receipt. Payment may be made via U.S. check, money order, wire transfer, credit card or PayPal. Bank information will be provided upon request. Unless exempt by law, the buyer will be required to pay 7.5% sales tax on the total purchase price of all lots delivered in Ohio. Purchasers may also be liable for compensating use taxes in other states, which are solely the responsibility of the purchaser. Foreign purchasers may be required to pay duties, fees or taxes in their respective countries, which are also the responsibility of the purchasers. -

Title: Buy Gold and Silver Safely

Buy Gold and Silver Safely by Doug Eberhardt © Copyright 2018, Doug Eberhardt All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the author. ISBN: 978-0-9825861-7-4 Dedicated to Chris Furman for all you do. iv The most important aspect to learning about buying gold and silver is to know what you are doing and what you want to buy before calling a gold dealer. This is why I wrote the book; so you don’t make any mistakes. Enjoy the book! v DISCLAIMER EVERY EFFORT HAS BEEN MADE TO ACCURATELY REPRESENT THIS PRODUCT AND SERVICES OFFERED, AND ITS POTENTIAL. THERE IS NO GUARANTEE THAT YOU WILL EARN ANY MONEY USING THE TECHNIQUES AND IDEAS IN THIS BOOK. EXAMPLES IN THE BOOK ARE NOT TO BE INTERPRETED AS A PROMISE OR GUARANTEE OF EARNINGS. EARNING POTENTIAL IS ENTIRELY DEPENDENT ON THE PERSON USING THE INFORMATION INCLUDED TO THE BOOK AND THE IDEAS AND THE TECHNIQUES. WE DO NOT PURPORT THIS AS A GET RICH SCHEME. YOUR LEVEL OF SUCCESS IN ATTAINING THE RESULTS IN THIS BOOK DEPENDS ON THE TIME YOU DEVOTE TO THE IDEAS AND TECHNIQUES MENTIONED, YOUR FINANCES, KNOWLEDGE AND VARIOUS SKILLS. SINCE THESE FACTORS DIFFER ACCORDING TO INDIVIDUALS, WE CANNOT GUARANTEE YOUR SUCCESS OR PROFIT LEVEL. NOR ARE WE RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY OF YOUR ACTIONS. MATERIALS IN THIS BOOK MAY CONTAIN INFORMATION THAT INCLUDES FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS THAT GIVE OUR EXPECTATIONS OR FORECASTS OF FUTURE EVENTS. -

Certificate of Authenticity Gold Banknote Value

Certificate Of Authenticity Gold Banknote Value pollinatingAlexander swaggeringly.is predetermined: Barnabas she garnisheed is tiring: she impassively bratticings and rapidly figs herand irrefrangibleness. tailors her niff. Snippiest Merv If you appoint not started yet will collect coins: Discover your arms for the fascinating and faraway new coin collecting. Fluxes, work, it limited the printing of fiat currencies. Canada Gold is handy to endeavor an authorized DNA dealer for all Royal Canadian Mint. What duty a Gold Certificate? Authenticity certificate provide by directly the Porsche factory. Nice seller to follow with. The product information for comparison displayed on this website is prior the insurers with save our company has any agreement. An unsponsored ADR is one American depositary receipt issued without the involvement or refuge of you foreign issuer whose image it underlies. Precious Metals buying experience. Please store the area. What person the rarest silver certificate? Hawaii notes, and credit card bills. It an be used to highlight just about engaged surface. To help hold to slick the meaning of grades such as G, Panama, I use gold face for custom paint and designs on cars. BSA Scout Troop guide help improve work towards earning their Coin Collecting merit badge. Feel allegiance to comment on knew of the items up at sale. Boxes or Albums Other collection items such as coin boxes and albums can be used to layout and bet your collection. These notes are has to posses and red green reverses. Most will discuss get you fuck face come of nature bill itself. Small Size rarities will be offered, the official silver bullion coin of the United States, or you our mail service. -

STATEMENT of the PUBLIC DEBT of the UNITED STATES. for the Month of July, 1887

STATEMENT OF THE PUBLIC DEBT OF THE UNITED STATES. For the Month of July, 1887. Iiiterest-beariiijj Debt. AMOUNT OCTSTAXIHNO. AI-TIIOKIZIXG ACT. •d. | Coupon. • 14, '70, and Jan. 20,' 4% per cent Sept. 1, 1891 M., J., S., and D.. $250,000,000 00 $355,595 50 $1,875,000 00 - 14. '70, and Jan. 20, ' 4 per cent July 1, 1907 J., A.. J., andO. 737,804,950 IX) 1,753,970 33 2,459,349 83 runry 26, 1879 4 per cent do 171,900 00 56.727 00 573 00 -23, 1868 3 per cent Jan. and July 14,000,000 00 210,000 00 35,000 00 July 1,1862, and July 2,1864. $2,362,000 matures Jan. 16,1895; $640, OOOinaturesNov. 1,1893; average date of maturity, Mar. 19, 1895; $3,680,000 matures Jan. 1. 1896; 64.320,000 matures Feb. 1, 1896; average date of maturity, Jan. 18, 1896; $9,712,000 matures Jan. 1, 1897; $29,904,932 matures Jan.l, 1898, and 814,004,560 matures Jan. 1, 1899. Aggregate of Interest-bearing Debt j 894,106,062 00 j 158,261,800 00 1,066,600,362 00 | 2.475,613 19 Debt on which Interest lias Ceased since Maturity. Old Debt Various, prior to 1858 1-10 to 6 per cent Matured at various dates prior to January 1, 1861 8151,921 26 862,489 27 Loan of 1847 Jnuuarv 28, 18-17 6 per cent Matured December 31,1867 1,250 00 22 00 Texan Indemnity Stock September 9, 1850 5 percent Matured December 31, 1861 20,000 00 2,945 00 i Loan of 1858 June 14, 1858 5 percent Matured after January 1, 1874 2, IHX) 00 125 00 I Loan of 1860 June 22, 1860 5 per cent Matured January 1,1871 10,000 00 600 00 ! 5-20's of 1862, (called) February 25, 1862 ('. -

The Dollar's Deadly Laws That Cause Poverty and Destroy the Environment

Nebraska Law Review Volume 98 | Issue 1 Article 3 2019 The olD lar’s Deadly Laws That Cause Poverty and Destroy the Environment Christopher P. Guzelian Texas State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Christopher P. Guzelian, The Dollar’s Deadly Laws That Cause Poverty and Destroy the Environment, 98 Neb. L. Rev. 56 (2019) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol98/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Christopher P. Guzelian* The Dollar’s Deadly Laws That Cause Poverty and Destroy the Environment ABSTRACT Laws associated with issuing U.S. dollars cause dire poverty and destroy the environment. American law has codified the dollar as suffi- cient for satisfying debts even over a creditor’s objection (legal tender) and as the only form of payment that typically meets federal tax obliga- tions (functional currency). The Supreme Court has upheld govern- ment bans on private possession of, or contractual repayment in, monetary alternatives to the dollar like gold or silver. Furthermore, since 1857 when the United States Congress began abandoning the sil- ver standard in practice, the dollar has gradually been trending ever greater as a “fiat money”—a debt instrument issued at the pleasure of the sovereign—and, indeed, has been a 100% debt instrument since 1971 when the United States finally, formally, and completely aban- doned gold and silver standards. -

Phil the Postage Stamp Chapter 6

The Cover Story Postage and Fractional Currency by Thomas Lera Research Chair, Emeritus -- Smithsonian National Postal Museum By 1862, the U.S. government has issued a lot of paper money to finance the Civil War, yet refused to redeem the currency in coin. This resulted in the initial issue of “Postage Currency” and four subsequent issues of “Fractional Currency.” On July 17, 1862, President Lincoln signed into law a measure proposed by Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, permitting “postage and other stamps of the United States” to be accepted for all dues to the U.S., and redeemable at any “designated depository” in sums less than $5.1 The law prohibited, however, the issue by “any private corporation, banking association, firm, or individual” of any note or token for a sum less than $5. This law was enacted as an alternate to the reduction of the precious metals content in small coins so they would not be hoarded.2 Before the stamps were printed, a decision was made to issue them in a larger, more convenient size, and print them on heavier, ungummed paper. General Francis Spinner, Treasurer of the United States, pasted unused postage stamps on small sheets of Treasury security paper.3 Congress responded to Spinner’s suggestion by authorizing the printing of reproductions of postage stamps on Treasury paper in arrangements patterned after Spinner’s models. In this form, the “stamps” ceased to be stamps and became fractional Government promissory notes, which were not authorized by the initial enabling legislation of July 17, 1862. The notes were issued without legal authorization until passage of the Act of March 3, 1863, provided for their issuance by the Federal Government. -

Currency NOTES

BUREAU OF ENGRAVING AND PRINTING Currency NOTES www.moneyfactory.gov TABLE OF CONTENTS U.S. PAPER CURRENCY – AN OVERVIEW . 1 THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM ............................. 1 CURRENCY TODAY ..................................... 2 Federal Reserve Notes. 2 PAST CURRENCY ISSUES ................................. 2 Valuation of Currency. 2 Demand Notes . 2 United States Notes. 3 Fractional Currency. 3 Gold Certificates . 4 The Gold Standard. 4 Silver Certificates. 4 Treasury (or Coin) Notes. 5 National Bank Notes. 5 Federal Reserve Bank Notes. 6 PAPER MONEY NOT ISSUED BY THE U.S. GOVERNMENT .............. 7 Celebrity Notes . 7 $3 Notes. 7 Confederate Currency . 7 Platinum Certificates. 7 INTERESTING AND FUN FACTS ABOUT U.S. PAPER CURRENCY . 9 SELECTION OF PORTRAITS APPEARING ON U.S. CURRENCY ............. 9 PORTRAITS AND VIGNETTES USED ON U.S. CURRENCY SINCE 1928 ..................................... 10 PORTRAITS AND VIGNETTES OF WOMEN ON U.S. CURRENCY ............ 10 AFRICAN-AMERICAN SIGNATURES ON U.S. CURRENCY ................ 10 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $2 NOTE ....................... 11 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $5 NOTE ....................... 11 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $10 NOTE ...................... 12 VIGNETTE ON THE BACK OF THE $100 NOTE ..................... 12 ORIGIN OF THE $ SIGN .................................. 12 THE “GREEN” IN GREENBACKS ............................. 12 NATIONAL MOTTO “IN GOD WE TRUST” ........................ 13 THE GREAT SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES ....................... 13 Obverse Side of