De Stijl, 1917-1928

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and Related Aspects of Dutch Architecture 1917-1930

25 March 2002 Art History W36456 The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and related aspects of Dutch architecture 1917-1930. Walter Gropius, Design for Director’s Office in Weimar Bauhaus, 1923 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building, Dessau 1925-26 [Cubism and Architecture: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Maison Cubiste exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, Paris 1912 Czech Cubism centered around the work of Josef Gocar and Josef Chocol in Prague, notably Gocar’s House of the Black Virgin, Prague and Apt. Building at Prague both of 1913] H.P. (Hendrik Petrus) Berlage Beurs (Stock Exchange), Amsterdam 1897-1903 Diamond Workers Union Building, Amsterdam 1899-1900 J.M. van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and P.L. Kramer’s work on the Sheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam 1911-16. Amsterdam School and in particular the project of social housing at Amsterdam South as well as other isolated housing estates in the expansion of the city. Michel de Klerk (Eigenhaard Development 1914-18; and Piet Kramer (De Dageraad c. 1920) chief proponents of a brick architecture sometimes called Expressionist Robert van t’Hoff, Villa ‘Huis ten Bosch at Huis ter Heide, 1915-16 De Stijl group formed in 1917: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerritt Rietveld and others (Van der Leck, Huzar, Oud, Jan Wils, Van t’Hoff) De Stijl (magazine) published 1917-31 and edited by Theo van Doesburg Piet Mondrian’s development of “Neo-Plasticism” in Painting Van Doesburg’s Sixteen Points to a Plastic Architecture Projects for exhibition at the Léonce Rosenberg Gallery, Paris 1923 (Villa à Plan transformable in collaboration with Cor van Eestern Gerritt Rietveld Red/Blue Chair c. -

Extended Sensibilities Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

CHARLEY BROWN SCOTT BURTON CRAIG CARVER ARCH CONNELLY JANET COOLING BETSY DAMON NANCY FRIED EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEDD GARET GILBERT & GEORGE LEE GORDON HARMONY HAMMOND JOHN HENNINGER JERRY JANOSCO LILI LAKICH LES PETITES BONBONS ROSS PAXTON JODY PINTO CARLA TARDI THE NEW MUSEUM FRAN WINANT EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART CHARLEY BROWN HARMONY HAMMOND SCOTT BURTON JOHN HENNINGER CRAIG CARVER JERRY JANOSCO ARCH CONNELLY LILI LAKICH JANET COOLING LES PETITES BONBONS BETSY DAMON ROSS PAXTON NANCY FRIED JODY PINTO JEDD GARET CARLA TARDI GILBERT & GEORGE FRAN WINANT LE.E GORDON Daniel J. Cameron Guest Curator The New Museum EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES STAFF ACTIVITIES COUNCJT . Robin Dodds Isabel Berley HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART Nina Garfinkel Marilyn Butler N Lynn Gumpert Arlene Doft ::;·z17 John Jacobs Elliot Leonard October 16-December 30, 1982 Bonnie Johnson Lola Goldring .H6 Ed Jones Nanette Laitman C:35 Dieter Morris Kearse Dorothy Sahn Maria Reidelbach Laura Skoler Rosemary Ricchio Jock Truman Ned Rifkin Charles A. Schwefel INTERNS Maureen Stewart Konrad Kaletsch Marcia Thcker Thorn Middlebrook GALLERY ATTENDANTS VOLUNTEERS Joanne Brockley Connie Bangs Anne Glusker Bill Black Marcia Landsman Carl Blumberg Sam Robinson Jeanne Breitbart Jennifer Q. Smith Mary Campbell Melissa Wolf Marvin Coats Jody Cremin This exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joanna Dawe the Arts in Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and is made possible in Jack Boulton Mensa Dente part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. Elaine Dannheisser Gary Gale Library of Congress Catalog Number: 82-61279 John Fitting, Jr. -

L'aubette 1928

« L’AUBETTE 1928 » VISITES GUIDÉES Téléchargez gratuitement Place Kléber Possibilité de visites guidées pour l’audio-guide de l’Aubette 1928 : les groupes aux horaires d’ouverture HORAIRES de l’Aubette. Du mercredi au samedi VISITES POUR LES SCOLAIRES de 14h à 18h : R. Aginako Imp. Int. C. U. Strasbourg U. C. Int. Aginako R. Imp. : Mercredis, jeudis et vendredis matin. : M. Bertola, M. : StrasbourgMuséesVille de la de L’AUBETTE 1928 Résa. au 03 88 88 50 50 (du lundi Entrée libre au vendredi de 8h 30 à 12h 30) WWW.MUSEES.STRASBOURG.EU Photos Graphisme L’AUBETTE 1928 BIOGRAPHIES LES ESPACES RESTITUÉS LA RESTAURATION L’AUBETTE 1928 L’AUBETTE ORIGINELLE L’AUBETTE AU XIXE ET DÉBUT DU XXE SIÈCLE L’INITIATIVE DES FRÈRES HORN DESCRIPTIF DU COMPLEXE La réalisation de l’Aubette est confiée en 1765 Après avoir abrité dès 1845 un café dans une Paul Horn réalise de 1922 à 1926 les premiers plans Le complexe de loisirs de l’Aubette comprend alors à l’architecte Jacques-François Blondel (1705- partie de ses locaux, l’Aubette accueille en 1869 intérieurs. Cette même année, les entrepreneurs quatre niveaux (sous-sol, rez-de-chaussée, entresol 1774). Faute de ressources suffisantes, le projet le musée municipal de peintures, créé en 1803, s’adjoignent les compétences de Hans Jean Arp et et premier étage) dont les trois artistes se répar- initial qui comprenait, outre le corps de bâtiment, qui sera ravagé par un incendie le 24 août 1870. Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Le couple d’artistes s’associe tissent la décoration. Seuls les espaces du premier le traitement symétrique de la place Kléber, est La réhabilitation du bâtiment intervient entre 1873 en septembre 1926 à Theo Van Doesburg, peintre étage, accueillant le Ciné-bal et la salle des fêtes aux abandonné. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

Mondrian and De Stijl

Exhibition November 11, 2020 – March 1, 2021 Sabatini Building, Floor 1 Mondrian and De Stijl Piet Mondrian, Lozenge Composition with Eight Lines and Red (Picture no. III), 1938 Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Beyeler Collection. © Mondrian/Holtzman, 2020 The work of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian within the context of the movement De Stijl [The Style] set the course of geometric abstract art from the Netherlands and contributed to the drastic change in visual culture after the First World War. His concept of beauty based on the surface, on the structure and composition of color and lines, shaped a novel and innovative style that aimed at breaking down the frontiers between disciplines and surpassing the traditional limits of pictorial space. De Stijl, the magazine of the same name founded in 1917 by the painter and critic Theo van Doesburg, was the platform for spreading the ideas of this new art and overcoming traditional Dutch provincialism. Contrary to what has often been said, the members of De Stijl did not pursue a utopia but a world where collaboration between all disciplines would make it possible to abolish hierarchies among the arts. These would thus be freed to merge together and give rise to something new, a reality better adapted to the world of modernity that was just starting to be glimpsed. Piet Mondrian (Amersfoort, Netherlands, 1872-New York, 1944) is considered one of the founders of this new art. His progressive ideas about the relationship between art and society grew from the deep- rooted Dutch realist tradition inherited from the seventeenth century. -

Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum

1 Guide to International Decorative Art Styles Displayed at Kirkland Museum (by Hugh Grant, Founding Director and Curator, Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art) Kirkland Museum’s decorative art collection contains more than 15,000 objects which have been chosen to demonstrate the major design styles from the later 19th century into the 21st century. About 3,500 design works are on view at any one time and many have been loaned to other organizations. We are recognized as having one of the most important international modernist collections displayed in any North American museum. Many of the designers listed below—but not all—have works in the Kirkland Museum collection. Each design movement is certainly a confirmation of human ingenuity, imagination and a triumph of the positive aspects of the human spirit. Arts & Crafts, International 1860–c. 1918; American 1876–early 1920s Arts & Crafts can be seen as the first modernistic design style to break with Victorian and other fashionable styles of the time, beginning in the 1860s in England and specifically dating to the Red House of 1860 of William Morris (1834–1896). Arts & Crafts is a philosophy as much as a design style or movement, stemming from its application by William Morris and others who were influenced, to one degree or another, by the writings of John Ruskin and A. W. N. Pugin. In a reaction against the mass production of cheap, badly- designed, machine-made goods, and its demeaning treatment of workers, Morris and others championed hand- made craftsmanship with quality materials done in supportive communes—which were seen as a revival of the medieval guilds and a return to artisan workshops. -

2 , 31 Octobre 2009 2 , 31 Oktober 2009

les journées de l’architecture architecture en mouvement(s) 2 , 31 octobre 2009 , oktober 2009 oktober 31 2 architektur in bewegung(en) in architektur die architekturtage die Karlsruhe Haguenau Drusenheim Baden-Baden Herrlisheim Mundolsheim Bühl Wiwersheim La Wantzenau Schiltigheim Strasbourg Molsheim Lingolsheim Illkirch- Graffenstaden Offenburg Stuttgart j Saint-Pierre Sélestat Colmar Freiburg im Breisgau Dessenheim Mulhouse Riedisheim Village-Neuf Weil am Rhein Rheinfelden Basel © Google Earth 2008 Il y a mille et une façons de « lire » l’architecture et trois façons de consulter ce programme… À vous de choisir le sommaire qui vous convient : par villes (ci-dessous), par manifestations (pages 2 à 5) ou par dates (en fi n de programme). Architektur lässt sich auf verschiedenste Arten „lesen“ und dieses Programm auf drei… Wählen Sie die Inhaltsübersicht aus, die Ihnen am Besten gefällt: geordnet nach Städten Bühl (siehe unten), nach Veranstaltungen (Seiten 2 bis 5) oder nach Datum (am Ende des Programms). ●F Pour un public francophone | Für französischsprachiges Publikum ●D Pour un public germanophone | Für deutschsprachiges Publikum Sans frontière 12 Baden-Baden 20 Basel 22 Colmar 26 Freiburg im Breisgau 30 Haguenau 40 Karlsruhe 42 Mulhouse 50 Offenburg 54 Schiltigheim 58 Sélestat 62 Strasbourg 70 Wiwersheim 104 + Bühl, Dessenheim, Drusenheim, Herrlisheim, Illkirch-Graffenstaden, Lingolsheim, Molsheim, Mundolsheim, Rheinfelden, Riedisheim, Saint-Pierre, Stuttgart, Village-Neuf, La Wantzenau, Weil am Rhein 2 MANIFESTATIONS | VERANSTALTUNGEN Ouverture | Eröffnung k MULHOUSE 10 Expositions | Ausstellungen Der Osten im Übergang – Grenzen in Bewegung 20 k BADEN-BADEN BBC : bâtiments basse consommation en Alsace 26 k ColmAR EPAPA : petits projets d’architecture des pays d’Alsace 27 k ColmAR Kunst bau werk II, Architektur-Blicke 30 k FREIbuRG IM BREISGAU Architekturfotografie: Tomas Riehle 31 k FREIbuRG IM BREISGAU 15. -

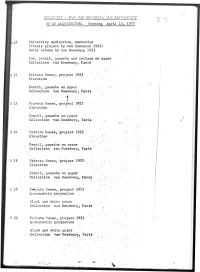

The Devk.Opment of an Architecture

/o n Glir.CKI.IST - THi-.O V.M^ DOESBURG: TIIK DEVKl.OrMEnT OF AH ARCHITECTURli: Opcntng April 10. 1970 3-7 10 University auditorium, Amatcrdam (Thesis project by van Eesteren 1922) Color scheme by van Doesburg 1923 Ink, pencil, gouache and collage on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris ^\ ' IB 12 Private House, project 1923 Elevation Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris D 13 Private House, project 1923 Elevation Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris U 14 Private House, project 1923 Elevation Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris B 15 Private House, project 1923 Elevation ' ' , Pencil, gouache on paper i\ ' Collection van Doesburg, Paris D 19 Pwivatc House, proj.ect 1923 A::onoinetric projection - Black and white print Collection van Doesburg, Paris ^ 20 Private House, project 1923 ' A::onomotrtc projection Black apd vhite print Collection van Doesburg, Paris t •••••• ^ I van Docoburs/2| B 23 Private H0U80, project 1923 A::onoinetrlc projection Dlack and vhlte print vlth gouache and collage Collection van Eesteren, Amstordam B 24 Private House, project 1923 ' Axonomotrtc projection,' Lithosraph , Collection van Doesburg, Paris ..;..: I', B 25 Private House, project 1923 Study for "Counter-Construction" Ink, couache on paper .^i /, Collection van Doesburg, Paris ; B 26 Private House, project 1923 Study for "Counter-Construction" Pencil, gouache on paper Collection van Doesburg, Paris' B 33 Private House, project 1923-24 V • 9> '"Counter-Construction"^ . / . Photomontage ' ' • .* Collection van Doesburg, Paris ; . B 27 Private House, project 1923 •"Counter-Cons truetlorf' Pencil and gouache on paper x Collection van Doesburg, Paris' B 28 Private House, project 1923^ v ' V "Counter-Construction" ! ' . -

Avant-Gardes in Yugoslavia

Filozofski vestnik | Letnik XXXVII | Številka 1 | 2016 | 201–219 Miško Šuvaković* Avant-Gardes in Yugoslavia In this study, I will approach the avant-gardes as interdisciplinary, internation- ally oriented artistic and cultural practices.1 I will present and advocate the the- sis that the Yugoslav avant-gardes were a special geopolitical and geo-aesthetic set of artistic and cultural phenomena defined by the internal dynamics and interrelations of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and by the external dynamics, cosmopolitan relations, and inter- nationalisations of local artistic excess and experimentation with international avant-garde practices. I will devote special attention to the local and interna- tional networking of cities as the political and cultural environments where the avant-gardes took place. Above all, the avant-gardes thereby acquired the char- acter of extremely urban artistic and cultural phenomena. Introductory Interpretation of the Concept of the Avant-garde Discussing the status, functions, and effects of any avant-garde does not boil down to asking what phenomenal or conceptual, i.e. formalist, qualities are characteristic of an avant-garde work of art, the behaviour of an avant-garde artist, or her private or public life. On the contrary, equally important are direc- tional questions regarding the instrumental potentialities or realisations of the avant-garde as an interventional material artistic practice in between or against dominant and marginal domains, practices, or paradigms within historical or 201 present cultures. Avant-garde artistic practices are historically viewed as trans- formations of artistic, cultural, and social resistances, limitations, and ruptures within dominant, homogeneous or hegemonic artistic, cultural, and social en- vironments. -

4 De Stijl: 'Manifesto L' S Theo Van Doesburg

IIIC Abstraction and Form 281 hnique tendency, led by Khlebnikov, to create a new and properly poetic language has fficulty emerged . In the light of these developments we can define poetry as attenuated, tortuous n itself speech. Poetic speech is formed speech. Prose is ordinary speech [ . .] ?bjec1 is 4 De Stijl: 'Manifesto l' 'arm is The De Stijl group was founded in Holland in 1917, dedicated to a synthesis of art, design and is this: architecture. Its leading figure was Theo van Doesburg. Other members included Gerrit ich are Rietveld and J. J. P. Ou d, both architect-designers, and the painters Georges Vantongerloo :reate a and Piet Mondrian. Links were established with the Bauhaus in Weimar Germany, and with ·ng as a similar projects in Russia, particularly through contacts with El Lissitsky. The 'Manifesto', principally the work of van Doesburg, was composed in 1918. ltwas published in the group's journal De Stijl, V, no. 4, Amsterdam, 1922. The present translation by Nicholas Bullock is taken from Stephen Bann (ed.), The Tradition of Constructivism, London, 197 4, p. 65. ; in its s com Ne find There is an old and a new consciousness of time. uthor's The old is connected with the individual. tion. A The new is connected with the universal. ,ossible The struggle of the individual against the universal is revealing itself in the world ;ky has war as well as in the art of the present day. ,articu 2 The war is destroying the old world and its contents: individual domination in Jficult, every state. -

International Style in Archıtecture Rietveld Art Deco

08.12.2011 ARCHITECTURE IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Adolf Loos & origins of the modern façade Cubism, De Stijl and New Conceptions of Space: The International Style in Archıtecture Rietveld Art Deco Week 11 WORLD HISTORY ART HISTORY ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY Wrights flight airplane 1903 Machintosh builds Hill House Einstein announces relativity theory 1905 First Fauve exhibit, Die Brücke founded Earthquake shakes San Francisco 1906 Gaudi starts building Casa Mila 1907 Brancusi carves first abstract sculpture 1908 Picasso and Braque found Cubism FAUVISM 1908-13 Ash Can painters introduced realism CUBISM EARLY Wright invents Prairie House 1910 Kandinsky paints first abstract canvas Adolf Loos builds Steiner house. 1911 Der Blaue Reiter formed Henry Ford develops assembly line 1913 Armory Show shakes up American art World War I declared 1914 CUBISM HIGH 1916 Dada begins FUTURISM Lenin leads Russian revolution 1917 De Stijl founded 1918 Bauhaus formed EXPRESSIONISM 1920s Mexican muralists active U.S. Women win vote 1920 Soviets suppress Constructivism LATE CUBISM LATE Hitler writes Mein Kampf 1924 Surrealists issue manifesto Gropius builds Bauhaus in Dessau Lindbergh flies solo across Atlantic 1927 Buckminister Fuller designs Dymaxian House Fleming discovers penicillin 1928 CONSTRUCTIVISM PRECISIONISM Stock Market crashes 1929 Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoy sets style for Modernism 1930s American scene painters popular, Social Realists paint political art Empire State Building opens FDR becomes President 1933 Commercial television begins 1939 U.S: enters WWII 1941 SURREALISM First digital computer developed 1944 Pope’s National Gallery is last major Classical building in U.S. Hiroshima hit with atom bomb 1945 Dubuffet coins term “L’Art Brut” Mahatma Gandhi assasinated, Israel founded 1948 People’s Republic of China founded 1949 Oral Contraceptive invented 1950 Abstract expressionism recognized 1952 Harold Rosenberg coins term “Action Painting” DNA structure discovered, Mt. -

Geoff Lucas -- Towards a Concrete

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Towards a Concrete Art A Practice-Led Investigation Lucas, Geoff Award date: 2015 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Towards a Concrete Art: A Practice-Led Investigation Geoff Lucas PhD Fine Art, (Full-time). Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design University of Dundee September 2010 - September 2015 Towards a Concrete Art: A Practice-Led Investigation Geoff Lucas Boyle Family: Loch Ruthven, 2010 Installation view 4 5 Contents 1.33 Can this dialogue operate without representational elements? 96 1.4 HICA Exhibition: Richard Couzins: Free Speech Bubble , 1 March–5 April 2009 98 List of Illustrations 10 1.41 Questioning the location of meaning 98 Abstract 15 1.42 Sign and signified; ‘outer’ and