6. Requiem by Karl Jenkins. an Analytical Approach to the Interweaving of Various Traditions in Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Clarinet Concerto in a Major, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 Mozart composed this concerto between the end of September and mid-November 1791, and it apparently was performed in Vienna shortly afterwards. The orchestra consists of two flutes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-nine minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was given at the Ravinia Festival on July 25, 1957, with Reginald Kell as soloist and Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra’s first subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on May 2, 1963, with Clark Brody as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on October 11 and 12, 1991, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra most recently performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 2001, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Andrew Davis conducting. This concerto is the last important work Mozart finished before his death. He recorded it in his personal catalog without a date, right after The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. The only later entry is the little Masonic Cantata, dated November 15, 1791. The Requiem, as we know, didn’t make it into the list. For decades the history of the Requiem was full of ambiguity, while that of the Clarinet Concerto seemed quite clear. But in recent years, as we learned more about the unfinished Requiem, questions about the concerto began to emerge. -

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

Requiem, Op. 48 Gabriel Fauré (1845 - 1924)

ASO Program Notes Requiem, Op. 48 Gabriel Fauré (1845 - 1924) Gabriel Fauré grew up in the French Pyrenees and began his musical education at a very early age. He studied organ, piano and choral music at increasingly more prestigious schools, ending up at the Niedermeyer School in Paris. His teachers included Camille Saint-Saëns. When he later became a teacher at the Paris Conservatory, Maurice Ravel and Nadia Boulanger were among his pupils. He served as organist and choirmaster at a number of large churches in Paris, and enjoyed an excellent reputation as a successful composer until he grew deaf and had to give up much of his musical life. There have been many famous Requiems, and all have their own style. Verdi, Berlioz, and Brahms all composed glorious Requiems addressing the themes of death, resurrection and final judgment. The tone of their works is grand and even theatrical. Mozart’s Requiem is moving and poignant. Fauré chose to make his gentler, full of solace and comfort for the mourners. It is also moving, but in a kinder, more consoling way. The awesome vision of “The Last Judgement” would have meant little to Fauré. In spite of the fact that most of his life had been dedicated to service to the church, he was an unbeliever, and so he focused more on the blessed rest for those whose life journey had come to an end. In Fauré’s words, “Everything I managed to entertain in the way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which is…dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest.” and at another time, “I see death as a happy deliverance, an aspiration towards happiness above, rather than as a painful experience.” Although firmly agnostic, he was a spiritual man, and sought to compose a newer kind of church music, different from the heavily romantic style of the German composers dominating European music at the time. -

Penderecki Has Enjoyed an International Reputation for Music That Blends Direct, Emotional Appeal with Contemporary Compositional Techniques

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Since 1966, with the composition of the St Luke Passion (Naxos 8.557149), Penderecki has enjoyed an international reputation for music that blends direct, emotional appeal with contemporary compositional techniques. The neo-Romantic choral work, Te Deum, was inspired by the anointing of Karol Wojtyla as the first Polish Pope in 1978. Although Penderecki’s recent choral works have tended to be similarly monumental in scale, he has written several of a more compact DDD PENDERECKI: nature, such as Hymne an den heiligen Daniel, whose opening ranks as one of the composer’s most PENDERECKI: affecting. This disc closes with two works for strings: the experimental Polymorphia from 1961, 8.557980 and the expressive Chaconne, written in 2005 as a tribute to the late Pope John Paul II. Krzysztof Playing Time PENDERECKI 67:06 (b. 1933) Te Deum Te Deum Te Te Deum (1979-80)* 36:46 Deum Te 1 Part One 13:02 2 Part Two 7:53 3 Part Three 15:51 4 Hymne an den heiligen Daniel (1997)† 12:14 www.naxos.com Made in the EU Kommentar auf Deutsch Booklet notes in English ൿ 5 Polymorphia (1961) 10:48 & 6 Polish Requiem: Chaconne (2005) 7:18 Ꭿ 2007 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Izabela Kłosi´nska, Soprano* • Agnieszka Rehlis, Mezzo-soprano* Adam Zdunikowski, Tenor* • Piotr Nowacki, Bass* Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir*† (Henryk Wojnarowski, choirmaster) Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Sung texts are available at www.naxos.com/libretti/557980.htm 8.557980 Recorded from 5th to 7th September, 2005 (tracks 1-3), and on 29th September, 2005 (track 4), 8.557980 at Warsaw Philharmonic Hall, Poland Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Lupa and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 1 and 4), and Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 2 and 3) • Publisher: Schott Musik Booklet notes: Richard Whitehouse • Cover image: Grey Black Cross by Sybille Yates (dreamstime.com). -

For OCKEGHEM

ss CORO hilliard live CORO hilliard live 2 Producer: Antony Pitts Recording: Susan Thomas Editors: Susan Thomas and Marvin Ware Post-production: Chris Ekers and Dave Hunt New re-mastering: Raphael Mouterde (Floating Earth) Translations of Busnois, Compère and Lupi by Selene Mills Cover image: from an intitial to The Nun's Priest's Tale (reversed) by Eric Gill, with thanks to the Goldmark Gallery, Uppingham: www.goldmarkart.com Design: Andrew Giles The Hilliard Ensemble David James countertenor Recorded by BBC Radio 3 in St Jude-on-the-Hill, Rogers Covey-Crump tenor Hampstead Garden Suburb and first broadcast on John Potter tenor 5 February 1997, the eve of the 500th anniversary Gordon Jones baritone of the death of Johannes Ockeghem. Previously released as Hilliard Live HL 1002 Bob Peck reader For Also available on coro: hilliard live 1 PÉROTIN and the ARS ANTIQUA cor16046 OCKEGHEM 2007 The Sixteen Productions Ltd © 2007 The Sixteen Productions Ltd N the hilliard ensemble To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs, visit www.thesixteen.com cor16048 The hilliard live series of recordings came about for various reasons. 1 Kyrie and Gloria (Missa Mi mi) Ockeghem 7:10 At the time self-published recordings were a fairly new and increasingly 2 Cruel death.... Crétin 2:34 common phenomenon in popular music and we were keen to see if 3 In hydraulis Busnois 7:50 we could make the process work for us in the context of a series of public concerts. Perhaps the most important motive for this experiment 4 After this sweet harmony... -

Faure Requiem Program V2

FAURÉ REQUIEM Conceived and directed by Barbara Pickhardt, Artistic Director Produced by Barbara Scharf Schamest Premiered: June 13, 2021 Ars Choralis Barbara Pickhardt, artistic director REQUIEM, Op. 48 (1893) Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Introit Brussels Choral Society Eric Delson, conductor Kyrie Ars Choralis Chamber Orchestra Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Offertory Ars Choralis Chuck Snyder, baritone Eribeth Chamber Players Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Sanctus The Dessoff Choirs Malcolm J. Merriweather, conductor Pie Jesu (Remembrances) Magna Graecia Flute Choir Carlo Verio Sirignano, guest conductor Sebastiano Valentino, music director Agnus Dei Ars Choralis Magna Graecia Flute Choir Carlo Verio Sirignano, guest conductor Chamber Orchestra Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Libera Me Ars Choralis Harvey Boyer, tenor Douglas Kostner, organ Barbara Pickhardt, conductor Memorial Prayers Tatjana Myoko Evan Pritchard Rabbi Jonathan Kligler Elizabeth Lesser Pastor Sonja Tillberg Maclary In Paradisum Brussels Choral Society Eric Delson, conductor 1 Encore Performances Pie Jesu Ars Choralis Amy Martin, soprano Eribeth Chamber Playersr Barbara Pickhardt, conductor In Paradisum The Dessoff Choirs Malcolm J. Merriweather, conductor About This Virtual Concert By Barbara Pickhardt The Fauré Requiem Reimagined for a Pandemic This virtual performance of the Fauré Requiem grew out of the need to prepare a concert while maintaining social distancing. We would surely have preferred to blend our voices as we always have, in a live performance. But the pandemic opened the door to a new and different opportunity. As we saw the coronavirus wreak havoc around the world, it seemed natural to reach out to our friends in other locales and include them in this program. In our reimagined version of the Fauré Requiem, Ars Choralis is joined, from Belgium, by the Brussels Choral Society, the Magna Graecia Flute Choir of Calabria, Italy, the Dessoff Choirs from New York City, and, from New York, instrumentalists from the Albany area, New York City and the Hudson Valley. -

“Ein Deutsches Requiem” De Brahms : Una Aproximación Hermeneútica

Scarabino, Guillermo Religiosidad en “Ein deutsches requiem” de Brahms : una aproximación hermeneútica Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Scarabino, Guillermo. “Religiosidad en Ein deutsches requiem de Brahms : una aproximación hermeneútica” [en línea]. Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” 26,26 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/religiosidad-ein-deutsches-requiem-brahms.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, Buenos Aires, 2012, pág. 657 RELIGIOSIDAD EN EIN DEUTSCHES REQUIEM DE BRAHMS. UNA APROXIMACIÓN HERMENÉUTICA GUILLERMO SCARABINO Resumen El Requiem Alemán de Brahms ha sido objeto de numerosos análisis teológico- musicológicos, debido principalmente a dos características peculiares: 1. es una obra del género requiem que no utiliza el texto de la Missa pro defunctis, sino que emplea una selección de textos bíblicos elegidos por su autor, y 2. su contenido motívico deriva de manipulaciones sobre la melodía del coral Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten, que aparecen a lo largo de los 7 números de la obra. Este trabajo pone de relieve la existencia de un motivo autónomo, independiente del contenido del coral, que aparece en cinco de los siete números y al que el autor asigna la representación simbólica de la Redención. -

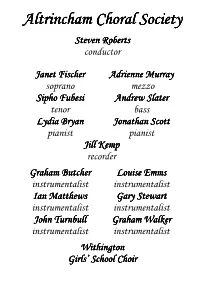

Steven Roberts Conductor

Altrincham Choral Society Steven Roberts conductor Janet FisFisccccherherherher Adrienne Murray soprano mezzo Sipho Fubesi Andrew Slater tenor bass Lydia Bryan Jonathan Scott pianist pianist Jill Kemp recorder Graham Butcher Louise Emms instrumentalist instrumentalist Ian Matthews Gary Stewart instrumentalist instrumentalist John Turnbull Graham Walker instrumentalist instrumentalist Withington Girls’ School Choir Altrincham Choral Society The Society invites our supporters to become Patrons or Sponsors of ACS. They receive advance publicity, complimentary tickets, reserved seating for performances and are acknowledged on the choir web-site and in all programmes. If you are interested in becoming a Patron or Sponsor of the society, please contact E Lawrence 01925 861862. ACS is grateful to the following for their continued support this season: Platinum Patrons Sir John Zochonis Gold Patrons Bernard H Lawrence John Kennedy Lee Bakirgian Family Trust Sponsors Faddies Dry Cleaners of Hale Florence Matthews Flowers by Remember Me of Hale Altrincham Choral Society Altrincham Choral Society prides itself in offering a diverse, innovative and challenging programme of concerts, including many choral favourites. A forward thinking and progressive nature at ACS is complemented by a commitment to choral training and standards which provides its members with the knowledge and confidence to thoroughly enjoy their music-making. Rehearsals are on Monday evenings at Altrincham Methodist Church, Springfield Road, Altrincham – off Woodlands Road (opposite the Cresta Court Hotel). We are only 5 minutes walk from the train/metro station. Rehearsals are from 7.45 to 10.00 pm For more information you can contact us in a variety of ways: E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: P Arnold (Secretary) 01270 764335 Or log onto our web-site www.altrincham-choral.co.uk where you can find more information about the choir, future plans, and photographs from previous concerts including Verona, Florence and the recent tour to Prague. -

The Music and Musicians of St. James Cathedral, Seattle, 1903-1953: the First 50 Years

THE MUSIC AND MUSICIANS OF ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL, SEATTLE, 1903-1953: THE FIRST 50 YEARS CLINT MICHAEL KRAUS JUNE 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of figures................................................................................................................... iii List of tables..................................................................................................................... iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 – Music at Our Lady of Good Help and St. Edward’s Chapel (1890- 1907)..................................................................................................................5 Seattle’s temporary cathedrals......................................................................5 Seattle’s first cathedral musicians ................................................................8 Alfred Lueben..................................................................................................9 William Martius ............................................................................................14 Organs in Our Lady of Good Help ............................................................18 The transition from Martius to Ederer.......................................................19 Edward P. Ederer..........................................................................................20 Reaction to the Motu Proprio........................................................................24 -

The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music

UCLA Recent Work Title The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9sn4k8dr ISBN 9780822372646 Author Eidsheim, Nina Sun Publication Date 2018-01-11 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Race of Sound Refiguring American Music A series edited by Ronald Radano, Josh Kun, and Nina Sun Eidsheim Charles McGovern, contributing editor The Race of Sound Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music Nina Sun Eidsheim Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Nina Sun Eidsheim All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Leigh Baker and typeset in Garamond Premier Pro by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Title: The race of sound : listening, timbre, and vocality in African American music / Nina Sun Eidsheim. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Series: Refiguring American music | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2018022952 (print) | lccn 2018035119 (ebook) | isbn 9780822372646 (ebook) | isbn 9780822368564 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isbn 9780822368687 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: African Americans—Music—Social aspects. | Music and race—United States. | Voice culture—Social aspects— United States. | Tone color (Music)—Social aspects—United States. | Music—Social aspects—United States. | Singing—Social aspects— United States. | Anderson, Marian, 1897–1993. | Holiday, Billie, 1915–1959. | Scott, Jimmy, 1925–2014. | Vocaloid (Computer file) Classification:lcc ml3917.u6 (ebook) | lcc ml3917.u6 e35 2018 (print) | ddc 781.2/308996073—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018022952 Cover art: Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2017. -

International Research and Exchanges Board Records

International Research and Exchanges Board Records A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by Karen Linn Femia, Michael McElderry, and Karen Stuart with the assistance of Jeffery Bryson, Brian McGuire, Jewel McPherson, and Chanté Wilson-Flowers Manuscript Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2011 International Research and Exchanges Board Records Page ii Collection Summary Title: International Research and Exchanges Board Records Span Dates: 1947-1991 (bulk 1956-1983) ID No: MSS80702 Creator: International Research and Exchanges Board Creator: Inter-University Committee on Travel Grants Extent: 331,000 items; 331 cartons; 397.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English and Russian Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: American service organization sponsoring scholarly exchange programs with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the Cold War era. Correspondence, case files, subject files, reports, financial records, printed matter, and other records documenting participants’ personal experiences and research projects as well as the administrative operations, selection process, and collaborative projects of one of America’s principal academic exchange programs. International Research and Exchanges Board Records Page iii Contents Collection Summary .......................................................... ii Administrative Information ......................................................1 Organizational History..........................................................2 -

The Grande Messe Des Morts (Requiem), Op. 5 by Hector Berlioz

THE GRANDE MESSE DES MORTS (REQUIEM), OP. 5 BY HECTOR BERLIOZ: A CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, ORCHESTRATION, RHETORICAL/DRAMA-LITURGICAL PROJECTION AND FORMAL/STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS BY KRISTOFER J. SANCHACK Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Jan Harrington, Research Director ______________________________________ Jan Harrington, Chair ______________________________________ Betsy Burleigh ______________________________________ Dominick DiOrio ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto 30 November 2015 ii Copyright © 2015 Kristofer J. Sanchack iii Dedicated to my parents and grandparents who have supported me through a very long process iv Acknowledgements There are so many people to whom I am extremely grateful. First I would like to thank my family. My parents, grandparents, sister and niece have continued each and every day to encourage me to finish this paper. Without their support, I doubt this project would have been completed. I also want to thank my partner, who throughout the process was supportive, helpful, understanding and caring. I would like to thank Dr. Carmen-Helena Téllez who began with me on this odyssey, and my mentor, friend and research chair Dr. Jan Harrington, who believed and continued to be a pillar of strength to me throughout this endeavor. I am also indebted to Dr. Betsy Burleigh, Dr. Dominick DiOrio and Dr. Frank Samarotto, who graciously agreed to serve on the committee for this paper.