The Historical Context for Indigenous Culture Change in Dixie Valley Is Critical When Considering the Nature and Causation of Such Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Indian Cri'm,Inal Justice

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. 1 I . ~ f .:.- IS~?3 INDIAN CRI'M,INAL JUSTICE 11\ PROG;RAM',"::llISPLAY . ,',' 'i\ ',,.' " ,~,~,} '~" .. ',:f,;< .~ i ,,'; , '" r' ,..... ....... .,r___ 74 "'" ~ ..- ..... ~~~- :":~\ i. " ". U.S. DE P ----''''---£iT _,__ .._~.,~~"ftjlX.£~~I.,;.,..,;tI ... ~:~~~", TERIOR BURE AIRS DIVISION OF _--:- .... ~~.;a-NT SERVICES J .... This Reservation criminal justice display is designed to provide information we consider pertinent, to those concerned with Indian criminal justice systems. It is not as complete as we would like it to be since reservation criminal justice is extremely complex and ever changing, to provide all the information necessary to explain the reservation criminal justice system would require a document far more exten::'.J.:ve than this. This publication will undoubtedly change many times in the near future as Indian communities are ever changing and dynamic in their efforts to implement the concept of self-determination and to upgrade their community criminal justice systems. We would like to thank all those persons who contributed to this publication and my special appreciation to Mr. James Cooper, Acting Director of the U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center, Mr •. James Fail and his staff for their excellent work in compiling this information. Chief, Division of Law Enforcement Services ______ ~ __ ---------=.~'~r--~----~w~___ ------------------------------------~'=~--------------~--------~. ~~------ I' - .. Bureau of Indian Affairs Division of Law Enforcement Services U.S. Indian Police Training and Research Center Research and Statistical Unit S.UMM.ARY. ~L JUSTICE PROGRAM DISPLAY - JULY 1974 It appears from the attached document that the United States and/or Indian tribes have primary criminal and/or civil jurisdiction on 121 Indian reservations assigned administratively to 60 Agencies in 11 Areas, or the equivalent. -

CMS Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives in California

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives in California Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) staff work with beneficiaries, health care providers, state government, CMS contractors, community groups and others to provide education and address questions in California. American Indians and Alaska Natives If you have questions about CMS programs in relation to American Indians or Alaska Natives: • email the CMS Division of Tribal Affairs at [email protected], or • contact a CMS Native American Contact (NAC). For a list of NAC and their information, visit https://go.cms.gov/NACTAGlist Why enroll in CMS programs? When you sign up for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or Medicare, the Indian health hospitals and clinics can bill these programs for services provided. Enrolling in these programs brings money into the health care facility, which is then used to hire more staff, pay for new equipment and building renovations, and saves Purchased and Referred Care dollars for other patients. Patients who enroll in CMS programs are not only helping themselves and others, but they’re also supporting their Indian health care hospital and clinics. Assistance in California To contact Indian Health Service in California, contact the California Area at (916) 930–3927. Find information about coverage and Indian health facilities in California. These facilities are shown on the maps in the next pages. Medicare California Department of Insurance 1 (800) 927–4357 www.insurance.ca.gov/0150-seniors/0300healthplans/ Medicaid/Children’s Health Medi-Cal 1 (916) 552–9200 www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal Marketplace Coverage Covered California 1 (800) 300–1506 www.coveredca.com Northern Feather River Tribal Health— Oroville California 2145 5th Ave. -

Pit River and Rock Creek 2012 Summary Report

Pit River and Rock Creek 2012 summary report October 9, 2012 State of California Department of Fish and Wildlife Heritage and Wild Trout Program Prepared by Stephanie Mehalick and Cameron Zuber Introduction Rock Creek, located in northeastern California, is tributary to the Pit River approximately 3.5 miles downstream from Lake Britton (Shasta County; Figure 1). The native fish fauna of the Pit River is similar to the Sacramento River and includes rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss sp.), sculpin (Cottus spp.), hardhead (Mylopharadon conocephalus), Sacramento sucker (Catostomus occidentalis), speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus) and Sacramento pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis; Moyle 2002). In addition, the Pit River supports a wild population of non-native brown trout (Salmo trutta). It is unknown whether the ancestral origins of rainbow trout in the Pit River are redband trout (O. m. stonei) or coastal rainbow trout (O. m. irideus) and for the purposes of this report, we refer to them as rainbow trout. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife Heritage and Wild Trout Program (HWTP) has evaluated the Pit River as a candidate for Wild Trout Water designation since 2008. Wild Trout Waters are those that support self-sustaining wild trout populations, are aesthetically pleasing and environmentally productive, provide adequate catch rates in terms of numbers or size of trout, and are open to public angling (Bloom and Weaver 2008). The HWTP utilizes a phased approach to evaluate designation potential. In 2008, the HWTP conducted Phase 1 initial resource assessments in the Pit River to gather information on species composition, size class structure, habitat types, and catch rates (Weaver and Mehalick 2008). -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCHES and STUDIES No 4, 2014 3 a Lithuanian “Ethnographic Village”: Heritage, Private Property

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCHES AND STUDIES No 4, 2014 A Lithuanian “Ethnographic Village”: Heritage, Private Property, Entitlement Kristina Jonutyte Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Address correspondence to: Kristina Jonutyte, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, PO Box 11 03 51, 06017 Halle (Saale) Germany. Ph.: +49 (0) 345 2927 0; Fax: +49 (0) 345 2927 502; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this article, various aspects of engagement with the past and with heritage are explored in the context of Grybija village in southern Lithuania. The village in question is a heritage site within an "ethnographic villages" programme, which was initiated by the Soviet state and continued by Independent Lithuania after 1990. The article thus looks at the ideological aspects of heritage as well as its practical implications to Grybija's inhabitants. Moreover, local ideas about private property, righteous ownership and entitlement are explored in their complexity and in relation to the heritage project. Since much of the preserved heritage in the village is private property, various restrictions and prohibitions are imposed on local residents, which are deemed as neither righteous nor effective by many locals. In the meantime, the discourse of the "ethnographic villages" project exotifies and distances the village and its inhabitants, constructing an "Other" that is both admired and alienated. Keywords: heritage site, private property, Lithuania. The fieldsite Grybija is a small village in the far South of Lithuania, Dzūkija region. There are around 50 permanent inhabitants and another dozen or so who stay for the summer, plus weekend visitors.1 The village is in the territory of Dzūkijos National Park which was established in order to protect the landscape as well as natural and cultural monuments of the region. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest

Area Adventure Hat Creek Ranger District Lassen National Forest Welcome The following list of recreation activities are avail- able in the Hat Creek Recreation Area. For more detailed information please stop by the Old Station Visitor Information Center, open April - December, or our District Office located in Fall River Mills. Give Hat Creek Rim Overlook - Nearly 1 million years us a call year-around Mon.- Fri. at (530) 336-5521. ago, active faulting gradually dropped a block of Enjoy your visit to this very interesting country. the Earth’s crust (now Hat Creek Valley) 1,000 feet below the top of the Hat Creek Rim, leaving behind Subway Cave - See an underground cave formed this large fault scarp. This fault system is still “alive by flowing lava. Located just off Highway 89, 1/4 and cracking”. mile north of Old Station junction with Highway 44. The lava tube tour is self guided and the walk is A heritage of the Hat Creek area’s past, it offers mag- 1/3 mile long. Bring a lantern or strong flashlight nificent views of Hat Creek Valley, Lassen Peak, as the cave is not lighted. Sturdy Shoes and a light Burney Mountain, and, further away, Mt. Shasta. jacket are advisable. Subway Cave is closed during the winter months. Fault Hat Creek Rim Fault Scarp Vertical movement Hat Creek V Cross Section of a Lava Tube along this fault system alley dropped this block of earth into its present position Spattercone Trail - Walk a nature trail where volca- nic spattercones and other interesting geologic fea- tures may be seen. -

Clifford-Ishi's Story

ISHI’S STORY From: James Clifford, Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the 21st Century. (Harvard University Press 2013, pp. 91-191) Pre-publication version. [Frontispiece: Drawing by L. Frank, used courtesy of the artist. A self-described “decolonizationist” L. Frank traces her ancestry to the Ajachmem/Tongva tribes of Southern California. She is active in organizations dedicated to the preservation and renewal of California’s indigenous cultures. Her paintings and drawings have been exhibited world wide and her coyote drawings from News from Native California are collected in Acorn Soup, published in 1998 by Heyday Press. Like coyote, L. Frank sometimes writes backwards.] 2 Chapter 4 Ishi’s Story "Ishi's Story" could mean “the story of Ishi,” recounted by a historian or some other authority who gathers together what is known with the goal of forming a coherent, definitive picture. No such perspective is available to us, however. The story is unfinished and proliferating. My title could also mean “Ishi's own story,” told by Ishi, or on his behalf, a narration giving access to his feelings, his experience, his judgments. But we have only suggestive fragments and enormous gaps: a silence that calls forth more versions, images, endings. “Ishi’s story,” tragic and redemptive, has been told and re-told, by different people with different stakes in the telling. These interpretations in changing times are the materials for my discussion. I. Terror and Healing On August 29th, 1911, a "wild man,” so the story goes, stumbled into civilization. He was cornered by dogs at a slaughterhouse on the outskirts of Oroville, a small town in Northern California. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

From Valley to Valley

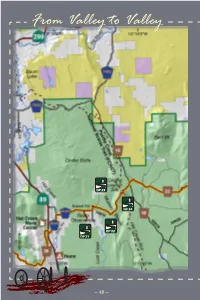

From Valley to Valley DP 23 DP 24 DP 22 DP 21 ~ 48 ~ Emigration in Earnest DP 25 ~ 49 ~ Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ValleyFrom to Valley Emigration in Earnest Section 5 Discovery Points 21 ~ 25 Distance ~ 21.7 miles eventually developed coincides he valleys of this region closely to the SR 44 Twere major thoroughfares for route today. the deluge of emigrants in the In 1848, Peter Lassen and a small 19th century. Linking vale to party set out to blaze a new trail dell, using rivers as high-speed into the Sacramento Valley and to transit, these pioneers were his ranch near Deer Creek. They intensely focused on finding the got lost, but were eventually able quickest route to the bullion of to join up with other gold seekers the Sacramento Valley. From and find a route to his land. His trail became known as the “Death valley to valley, this land Route” and was abandoned within remembers an earnest two years. emigration. Mapquest, circa 1800 During the 1800s, Hat Creek served as a southern “cut-off” from the Pit River allowing emigrants to travel southwest into the Sacramento Valley. Imagine their dismay upon reaching the Hat Creek Rim with the valley floor 900 feet below! This escarpment was caused by opposite sides of a fracture, leaving behind a vertical fault much too steep for the oxen teams and their wagons to negotiate. The path that was Photo of Peter Lassen, courtesy of the Lassen County Historical Society Section 5, Emigration in Earnest ~ 50 ~ Settlement in Fall River and Big Valley also began to take shape during this time. -

Black Lives Matter and Ethnographic Museums

ICME NEWS ISSUE 90 AUGUST 2020 black lives matter and etHnographic museums A statement from ICME Committee Announcements AND NEWS / Exhibitions and Conferences: Announcements and Reviews / ARTICLES / NOTICES ICME NEWS 90 AUGUST 2020 2 CONTENTS Words from the Editor .........................................................3 ICME Board Announcements and News Black Lives Matter and Ethnographic Museums: A Statement from ICME .........................................................4 Postponement of the 2020 ICME Conference ........................5 Exhibitions and Conferences: Announcements and Reviews Conference Review: Absence and Belonging in Museums of Everyday Life – Laurie Cosmo ...............................................6 Conference Review: Beyond collecting; new ethics for museums in transition – Flower Manasse .................................13 Conference Announcement: Anthropology and Geography ......15 Conference Announcement: Mapping South-South Connections ..........................................................16 Film Review: Bang the Drum – Jenny Walklate .......................17 Articles How can Museums Challenge Racism and Colonial Fantasies? - Boniface Mabanza in conversation with Anette Rein ............19 Getting out, getting in: Amerindian and European perspectives around the museum - Rui Mourão .........................25 Kurmanjan Datka. Museum of Nomadic Civilization, The Kyrgyz Republic - Aida Alymova and Gulbara Abdykalykova .............29 Beyond Trophies and Spoils of Wars - Staci-Marie Dehaney ........33