Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phantom Captain in Wakeathon

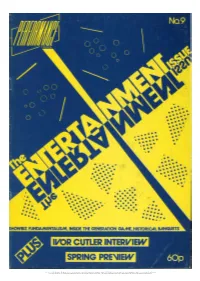

... • • • •• • • • •• • • • • • •• • • •I • • • • ' • • ( • ..• •.• ., .,,. .. , ••• .• • . • • •• • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • •"' • •. • .••• . ' . J '•• • - - • • • • • .• ...• • . • • • •• • • • • • • •• • ••• • ••••••••• • • • •••••• • • • • • • ••••• . • f • ' • • • ••• • •• • • •f • .• . • •• • • ., • , •. • • • •.. • • • • ...... ' • •. ... ... ... • • • • • ,.. .. .. ... - .• .• .• ..• . • . .. .. , • •• . .. .. .. .. • • • • .; •••• • •••••••• • 4 • • • • • • • • ••.. • • • •"' • • • • •, • -.- . ~.. • ••• • • • ...• • • ••••••• •• • 6 • • • • • • ..• -•• This issue of Performance Magazine has been reproduced as part of Performance Magazine Online (2017) with the permission of the surviving Editors, Rob La Frenais and Gray Watson. Copyright remains with Performance Magazine and/or the original creators of the work. The project has been produced in association with the Live Art Development Agency. NEW DANCE THEATRE IN THE '80s? THE ONLY MAGAZINE BY FOR AND ABOUT TODAYS DANCERS "The situation in the '80s will challenge live theatre's relevance, its forms, its contact with people, its experimentation . We believe the challenge is serious and needs response. We also believe that after a decade of 'consolidation' things are livening up again. Four years ago an Honours B.A. Degree in Theatre was set up at Dartington College of Arts to meet the challenge - combining practice and theory, working in rural and inner-city areas, training and experimenting in dancing, acting, writing, to reach forms that engage people. Playwrights, choreographers -

Translation in the Work of Omer Fast Kelli Bodle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 (Mis)translation in the work of Omer Fast Kelli Bodle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Bodle, Kelli, "(Mis)translation in the work of Omer Fast" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 4069. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4069 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (MIS)TRANSLATION IN THE WORK OF OMER FAST A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Kelli Bodle B.A., Michigan State University, 2002 August 2007 Table of Contents Abstract……...……………………………………………………………………………iii Chapter 1 Documentary and Alienation: Why Omer Fast’s Style Choice and Technique Aid Him in the Creation of a Critical Audience……………………………… 1 2 Postmodern Theory: What Aspects Does Fast Use to Engage Audiences and How Are They Revealed in His Work……………………………………….13 3 Omer Fast as Part of a Media Critique……………………….………………31 4 Artists and Ethics……………….……………………………………………39 5 (Dis)Appearance of Ethics in Omer Fast’s Videos..…………………………53 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..64 Vita...……………………………………………………………………………………..69 ii Abstract For the majority of people, video art does not have a major impact on their daily lives. -

Williams-Exeter Programme at Oxford University

WILLIAMS-EXETER PROGRAMME AT OXFORD UNIVERSITY Director: Professor Gretchen Long THE PROGRAMME Williams College offers a year-long program of studies at Oxford University in co-operation with Exeter College (founded in 1314), one of the constituent colleges of the University. Williams students will be enrolled as Visiting Students at Exeter and as such will be undergraduate members of the University, eligible for access to virtually all of its facilities, libraries, and resources. As Visiting Students in Oxford, students admitted to the Programme will be fully integrated into the intellectual and social life of one of the world’s great universities. Although students on the Programme will be members of Exeter College, entitled to make full use of Exeter facilities (including the College Library), dine regularly in Hall, and join all College clubs and organizations on the same terms as other undergraduates at Exeter, students will reside in Ephraim Williams House, a compound of four buildings owned by Williams College, roughly 1.4 miles north of the city centre. Up to six students from Exeter College will normally reside in Ephraim Williams House each year, responsible for helping to integrate Williams students into the life of the College and the University. A resident director (and member of the Williams faculty) administers Ephraim Williams House, oversees the academic program, and serves as both the primary academic and personal advisor to Williams students in Oxford. Students on the Williams-Exeter Programme are required to be in residence in Oxford from Tuesday, 25 September 2018, until all academic work for Trinity term is complete (potentially as late as at least 28 June 2019) with two breaks for vacations between the three terms. -

Iain Sinclair and the Psychogeography of the Split City

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Iain Sinclair and the psychogeography of the split city https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40164/ Version: Full Version Citation: Downing, Henderson (2015) Iain Sinclair and the psychogeog- raphy of the split city. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 IAIN SINCLAIR AND THE PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY OF THE SPLIT CITY Henderson Downing Birkbeck, University of London PhD 2015 2 I, Henderson Downing, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Iain Sinclair’s London is a labyrinthine city split by multiple forces deliriously replicated in the complexity and contradiction of his own hybrid texts. Sinclair played an integral role in the ‘psychogeographical turn’ of the 1990s, imaginatively mapping the secret histories and occulted alignments of urban space in a series of works that drift between the subject of topography and the topic of subjectivity. In the wake of Sinclair’s continued association with the spatial and textual practices from which such speculative theses derive, the trajectory of this variant psychogeography appears to swerve away from the revolutionary impulses of its initial formation within the radical milieu of the Lettrist International and Situationist International in 1950s Paris towards a more literary phenomenon. From this perspective, the return of psychogeography has been equated with a loss of political ambition within fin de millennium literature. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica ISSN: 1989-8975 Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública (INAP) Forte, Pierpaolo Breves consideraciones sobre la adquisición de obras de arte en la regulación europea de los contratos públicos Revista de Estudios de la Administración Local y Autonómica, núm. 8, 2017, Noviembre-Abril, pp. 97-115 Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública (INAP) DOI: 10.24965/reala.v0i8.10436 Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=576462577005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Recibido: 22-06-2017 Aceptado: 09-10-2017 DOI: 10.24965/reala.v0i8.10436 Breves consideraciones sobre la adquisición de obras de arte en la regulación europea de los contratos públicos Brief considerations on the acquisition of works of art in the European regulation of public contracts Pierpaolo Forte Università degli studi del Sannio [email protected] RESUMEN La obra, renunciando a una definición precisa de arte, reconoce que hay objetos de arte y objetos culturales, que, propiamente en esa capacidad, son relevantes también en términos legales, y trata de avanzar algunas reflexiones sobre la relevancia del arte en relación con la disciplina europea de contratos públicos y, en particular, con lo que puede deducirse de la Directiva 2014/24/UE, que puede entenderse como una especie de signo cultural capaz de ofrecer indicaciones sobre cómo se percibe el arte en Europa, también en términos políticos, en esta fase histórica. -

Frameworks for the Downtown Arts Scene

ACADEMIC REGISTRAR ROOM 261 DIVERSITY OF LONDON 3Ei’ ATE HOUSE v'Al i STREET LONDON WC1E7HU Strategy in Context: The Work and Practice of New York’s Downtown Artists in the Late 1970s and Early 1980s By Sharon Patricia Harper Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art at University College London 2003 1 UMI Number: U602573 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602573 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The rise of neo-conservatism defined the critical context of many appraisals of artistic work produced in downtown New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Although initial reviews of the scene were largely enthusiastic, subsequent assessments of artistic work from this period have been largely negative. Artists like Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kenny Scharf have been assessed primarily in terms of gentrification, commodification, and political commitment relying upon various theoretical assumptions about social processes. The conclusions reached have primarily centred upon the lack of resistance by these artists to post industrial capitalism in its various manifestations. -

King's Research Portal

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/10286632.2018.1557651 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Lee, H-K. (2019). The new patron state in South Korea: cultural policy, democracy and the market economy. International journal of cultural policy, 25(1), 48-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2018.1557651 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

News Competitions Diary Dates and More… Free Phone Card with the ‘BANGLA CALLING’ 660Ml Bottle Top Promotion

thestarISSUE 9 2009 FREE Don’t miss our interview with David Roper, the ‘piano’ in 4 Poofs and a Piano ✚ News Competitions Diary dates and more… Free Phone Card with the ‘BANGLA CALLING’ 660ml bottle top promotion “When your customer orders a beer go to the fridge and open a bottle of 660ml Bangla Premium Beer. Check the bottle top, if it reads Bangla on both sides you’re a winner” 1 in every 20 bottles is a winner... Good Luck! 1000’s of free Bangla Beer phone cards have been won, determined by ‘Bangla’ printed inside the bottle cap. Check to see if you’re a winner! To enter is Free of charge, for full terms and conditions please visit www.banglabeer.co.uk BOTTLED BANGLA 2007 INTERNATIONAL MONDE GOLD AWARD BANGLA BOTTLES Shapla Paani is a natural spring water. Being drawn deep through great british granite gives Shapla Paani its exceptional thirst quenching taste. A spring situated on the edge of Bodmin Moor in the picturesque and dramatic setting of Rough Tor. The bottling plant stands on an underground lake where pure Cornish moorland kissed rainfall naturally filters through the rock to produce a pure natural spring water. Why Stock Shapla Paani? • Shapla Paani spring water is specifically designed to fit into the Asian restaurant market. • Shapla Paani is exclusive to the on-trade, so it won’t be de-valued in your local supermarket. • Premium product, the quality and purity of this spring water is exceptional. • Available in 24x330ml and 12x750ml NRB cases. • Available in both Sparkling and Still variants. -

William Hope Hodgson's Borderlands

William Hope Hodgson’s borderlands: monstrosity, other worlds, and the future at the fin de siècle Emily Ruth Alder A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 © Emily Alder 2009 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter One. Hodgson’s life and career 13 Chapter Two. Hodgson, the Gothic, and the Victorian fin de siècle: literary 43 and cultural contexts Chapter Three. ‘The borderland of some unthought of region’: The House 78 on the Borderland, The Night Land, spiritualism, the occult, and other worlds Chapter Four. Spectre shallops and living shadows: The Ghost Pirates, 113 other states of existence, and legends of the phantom ship Chapter Five. Evolving monsters: conditions of monstrosity in The Night 146 Land and The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’ Chapter Six. Living beyond the end: entropy, evolution, and the death of 191 the sun in The House on the Borderland and The Night Land Chapter Seven. Borderlands of the future: physical and spiritual menace and 224 promise in The Night Land Conclusion 267 Appendices Appendix 1: Hodgson’s early short story publications in the popular press 273 Appendix 2: Selected list of major book editions 279 Appendix 3: Chronology of Hodgson’s life 280 Appendix 4: Suggested map of the Night Land 281 List of works cited 282 © Emily Alder 2009 2 Acknowledgements I sincerely wish to thank Dr Linda Dryden, a constant source of encouragement, knowledge and expertise, for her belief and guidance and for luring me into postgraduate research in the first place. -

Elizabethirvinephdthesis.Pdf (8.438Mb)

CONTINUITY IN INTERMITTENT ORGANISATIONS: THE ORGANISING PRACTICES OF FESTIVAL AND COMMUNITY OF A UK FILM FESTIVAL Elizabeth Jean Irvine A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6901 This item is protected by original copyright Continuity in Intermittent Organisations: The Organising Practices of Festival and Community of a UK Film Festival Elizabeth Jean Irvine Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews June 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis considers the relationship between practices, communities and continuity in intermittent organisational arrangements. Cultural festivals are argued to offer one such particularly rich and nuanced research context; within this study their potential to transcend intermittent enactment emerged as a significant avenue of enquiry. The engagement of organisation studies with theories of practice has produced a rich practice-based corpus, diverse in both theoretical concerns and empirical approaches to the study of practice. Nevertheless, continuity presents an, as yet, under- theorised aspect of this field. Thus, the central questions of this thesis concern: the practices that underpin the enactment of festivals; the themes emerging from these practices for further consideration; and relationships between festivals and the wider context within which they are enacted. These issues were explored empirically through a qualitative study of the enactment of a community-centred film festival. Following from the adoption of a ‘practice-lens approach’, this study yielded forty-eight practices, through which to explore five themes emerging from analysis: Safeguarding, Legitimising, Gatekeeping, Connecting and Negotiating Boundaries. -

Internationale Situationniste 79 a Special Issue Guesteditor, Thomas F Mcdonough

Art Theory Criticism Politics OCTOBER Guy Debord and the Internationale situationniste 79 A Special Issue Guesteditor, Thomas F McDonough Thomas F. McDonough RereadingDebord, Rereading the Situationists T.J. Clark and WhyArt Can't Kill the Donald Nicholson-Smith Situationist International Claire Gilman AsgerJorn'sAvant-Garde Archives Vincent Kaufmann Angels of Purity Kristin Ross Lefebvreon the Situationists: An Interview Situationist Textson Visual Culture and Urbanism:A Selection $10.00 / Winter 1997 Publishedby theMIT Press 79 Thomas F. McDonough Rereading Debord, Rereading the Situationists 3 T.J. Clark and WhyArt Can't Kill the Donald Nicholson-Smith Situationist International 15 Claire Gilman AsgerJorn's Avant-Garde Archives 33 Vincent Kaufmann Angels of Purity 49 Kristin Ross Lefebvreon the Situationists: An Interview 69 Situationist Texts on Visual Culture and Urbanism: A Selection 85 Cover photo: AsgerJorn. The Avant-Garde Doesn't Give Up. 1962. Rereading Debord, Rereading the Situationists* THOMAS F McDONOUGH "He must be read and reread, for the same phrases are always cited. He is reduced to a few formulas, at best out of nostalgia but more often in a negative sense, as if to say: look at where thinking like that gets you!"' So cautioned Philippe Sollers one week after Guy Debord's suicide on November 30, 1994. It is advice well taken, if recent glosses on the life and work of this founding member of the Situationist International are any indication. When, twenty-odd years after the publication of his Societedu spectacle(1967), Debord circulated his Commentaires on this book (1988), it was greeted with general skepticism. The reviewer for Le Mondeconceded the verity of its characterizations: Can we decide against him, when he emphasizes the generalized secrecy predominant in this gray world? The more we speak of transparency, the less we know who controls what, who manipulates whom, and to what end. -

YOU KILLED ME FIRST the Cinema of Transgression Press Release

YOU KILLED ME FIRST The Cinema of Transgression Press Release February 19 – April 9, 2012 Opening: Saturday, February 18, 2012, 5–10 pm Press Preview: Friday, February 17, 2012, 11 am Karen Finley, Tessa Hughes-Freeland, Richard Kern, Lung Leg, Lydia Lunch, Kembra Pfahler, Casandra Stark, Tommy Turner, David Wojnarowicz, Nick Zedd “Basically, in one sentence, give us the definition of the ‚Cinema of Transgression’.” Nick Zedd: “Fuck you.” In the 1980s a group of filmmakers emerged from the Lower East Side, New York, whose shared aims Nick Zedd later postulated in the Cinema of Transgression manifesto: „We propose … that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. … We propose to go beyond all limits set or prescribed by taste, morality or any other traditional value system shackling the minds of men. … There will be blood, shame, pain and ecstasy, the likes of which no one has yet imagined.“ While the Reagan government mainly focused on counteracting the decline of traditional family values, the filmmakers went on a collision course with the conventions of American society by dealing with life in the Lower East Side defined by criminality, brutality, drugs, AIDS, sex, and excess. Nightmarish scenarios of violence, dramatic states of mind, and perverse sexual abysses – sometimes shot with stolen camera equipment, the low budget films, which were consciously aimed at shock, provocation, and confrontation, bear witness to an extraordinary radicality. The films stridently analyze a reality of social hardship met with sociopolitical indifference. Although all the filmmakers of the Cinema of Transgression shared a belief in a radical form of moral and aesthetic transgression the films themselves emerged from an individual inner necessity; thus following a very personal visual sense and demonstratively subjective readings of various living realities.