When Privacy Almost Won: Time, Inc. V. Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application, Hearing on High School Plans

ull Local Coverage Complete Newt, Pictures Newspaper Devoted Presented Fairly, dearly And Impartially Each Wr<»k |hc Community Interurt Snbepentient - leaber PRICE FIVK CENTS ;iS SIM nil'l ''1,193 WOODHHIiXiK. N. J , THURSDAY, JUNK 7, 1951 N J, actuation At Testimonial Dinner for Monsignor McCorristin StfltP f^alift fnr •m ulalc bid; Topic • i ii inn mmmm IT im •••••• MIIIII— \jailO LKJl Music' Application, Hearing •*a „ M.T Received •)•£', in KxerciscB " ,n| in Stadium On High School Plans ,||)(if: -- "MUSiC" Wft: ( me sixty-fifth an- ,',,-,'mpnt exercises of Two Youths, Who Stole Car Here, Boaid is Mum inch School at the ,,, 'IlUnt When 223 ,.,,,! diplomas. Nabbed as Wreck Climaxes Chase Oh Plea Other ,,.,,; wore suns hy the ,,,,;,linK "qde to Amer- WOODBRIDGE—Two Perth Amboy youths, one of whom j StUUY l)t* Mticlc* '.',,,, Your'SonW" ««« escaped froiti the State Home for Boys in Jamesbiirg, Moli- » J (••,nl" • , day, are still being questioned by local police this morning WOODBRIDGE-"A oompirtc set ;,,..,s of welcome, Ken- lifter they miraculously escaped injury yesterday when a;of new dnUt ami 1U1 :,ddu,ional ,';. [,on said In part; large car they had stolon from a local auto dealer over- stlll remain to be com- fc A,)• music is the theme of th hd tl f ll t dl e turned after a hectic chase near Freehold, pleted before the Board of EducR- 'mirement exercises. tion learns whether its $3,000,000 „.,.,, denned as ft pleas- The two ore Anthony Luqualta. - "~ 14 Merldlth Street, escapee, and liiKh school plans will be approved ,„ of harmonious Fucing Trial hy State authorities ln Trenton. -

The Functional Music of Gail Kubik: Catalyst for the Concert Hall

The Functional Music of Gail Kubik: Catalyst for the Concert Hall Alfred W. Cochran From the late 1930s through the mid-1960s, three composers for the concert hall profoundly influenced American music and exerted a strong influence upon music in the cinema-Virgil Thomson (1896-1989), Aaron Copland (1900-90), and Gail Kubik (1914-84). Each won the Pulitzer prize in music, and two of those awards, Thomson's and Kubik's, were derived from their film scores. 1 Moreover, both Thomson and Copland earned Academy Awards for their film work. 2 All three men drew concert works from their film scores, but only Kubik used functional music as a significant progenitor for other pieces destined for the concert hall. An examination of his oeuvre shows an affinity for such transformations. More common, perhaps, was the practice of composers using ideas derived from previously composed works when writing a film score. In Kubik's case, the opposite was true; his work for radio, films, and television provided the impetus for a significant amount of his nonfunctional music, including chamber pieces and orchestral works of large and small dimension. This earned well-deserved praise, including that of Nadia Boulanger, who was Kubik's teacher and steadfast friend. Kubik was a prodigy-the youngest person to earn a full scholarship to the Eastman School of Music, its youngest graduate (completing requirements in both violin and composition), a college teacher at nineteen, the MacDowell Colony'S youngest Fellow, and the youngest student admitted to Harvard University'S doctoral program in music. In 1940, he left the faculty of Teachers College, Columbia University and became staff composer and music program advisor for NBC. -

The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir

1 Murder, Mugs, Molls, Marriage: The Broken Ideals of Love and Family in Film Noir Noir is a conversation rather than a single genre or style, though it does have a history, a complex of overlapping styles and typical plots, and more central directors and films. It is also a conversation about its more common philosophies, socio-economic and sexual concerns, and more expansively its social imaginaries. MacIntyre's three rival versions suggest the different ways noir can be studied. Tradition's approach explains better the failure of the other two, as will as their more limited successes. Something like the Thomist understanding of people pursuing perceived (but faulty) goods better explains the neo- Marxist (or other power/conflict) model and the self-construction model. Each is dependent upon the materials of an earlier tradition to advance its claims/interpretations. [Styles-studio versus on location; expressionist versus classical three-point lighting; low-key versus high lighting; whites/blacks versus grays; depth versus flat; theatrical versus pseudo-documentary; variety of felt threat levels—investigative; detective, procedural, etc.; basic trust in ability to restore safety and order versus various pictures of unopposable corruption to a more systemic nihilism; melodramatic vs. colder, more distant; dialogue—more or less wordy, more or less contrived, more or less realistic; musical score—how much it guides and dictates emotions; presence or absence of humor, sentiment, romance, healthy family life; narrator, narratival flashback; motives for criminality and violence-- socio- economic (expressed by criminal with or without irony), moral corruption (greed, desire for power), psychological pathology; cinematography—classical vs. -

Funny Games and the History of Hostage Noir

ANN NO STOCKS SAVAGE NO SPORTS TRIBUTE ™ ALL NOIR www.noircity.com www.filmnoirfoundation.org VOL. 4 NO. 1 CCCC**** A PUBLICATION OF THE FILM NOIR FOUNDATION BIMONTHLY 2 CENTS MARCH / APRIL 2009 BLACK AND WHITE AND READ ALL OVER IN MEMORIAM DAHL, DEADLINES ANN SAVAGE DOMINATE NC7 By Haggai Elitzur Special to the Sentinel n e l or January, San Francisco’s weather was l A . unusually warm and sunny, but the atmos- M d phere was dark and desperate indoors at the i v F a Castro Theatre, as it always is for the NOIR CITY D film festival. On this, the festival’s seventh outing, Eddie Muller and Arlene Dahl onstage at the Castro most of the selections fell into the theme of news- paper noir. tive MGM when Warner Bros. was tardy in re- upping her contract. Arlene Dahl: Down-to-Earth Diva Dahl described meeting a large group of This year’s special guest was the still-beauti- friendly stars, including Gary Cooper, on her very ful redhead Arlene Dahl, whose two 1956 features first day on the Warner Bros. lot. She also offered screened as a double bill. Wicked as They Come some brief details about her two-year involvement By Eddie Muller was a British production featuring Dahl as a social with JFK, which was set up by Joe Kennedy him- Special to the Sentinel climber seducing her way across Europe. Slightly self. It was a spellbinding interview with a great Scarlet, a Technicolor noir filmed by John Alton, star; Dahl made it clear that she loved the huge ANN SAVAGE CHANGED MY LIFE . -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Judicial Genealogy (And Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts

The Judicial Genealogy (and Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts BRAD SNYDER* During his Supreme Court nomination hearings, John Roberts idealized and mythologized the first judge he clerkedfor, Second Circuit Judge Henry Friendly, as the sophisticated judge-as-umpire. Thus far on the Court, Roberts has found it difficult to live up to his Friendly ideal, particularlyin several high-profile cases. This Article addresses the influence of Friendly on Roberts and judges on law clerks by examining the roots of Roberts's distinguishedyet unrecognized lineage of former clerks: Louis Brandeis 's clerkship with Horace Gray, Friendly's clerkship with Brandeis, and Roberts's clerkships with Friendly and Rehnquist. Labeling this lineage a judicial genealogy, this Article reorients clerkship scholarship away from clerks' influences on judges to judges' influences on clerks. It also shows how Brandeis, Friendly, and Roberts were influenced by their clerkship experiences and how they idealized their judges. By laying the clerkship experiences and career paths of Brandeis, Friendly, and Roberts side-by- side in detailed primary source accounts, this Article argues that judicial influence on clerks is more professional than ideological and that the idealization ofjudges and emergence of clerks hips as must-have credentials contribute to a culture ofjudicial supremacy. * Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Thanks to Eleanor Brown, Dan Ernst, David Fontana, Abbe Gluck, Dirk Hartog, Dan -

A View from the Bridge

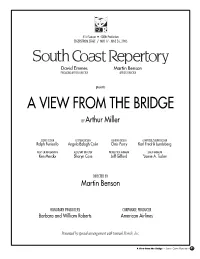

41st Season • 400th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / MAY 17 - JUNE 26, 2005 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE BY Arthur Miller SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN COMPOSER/SOUND DESIGN Ralph Funicello Angela Balogh Calin Chris Parry Karl Fredrik Lundeberg FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER Ken Merckx Sharyn Case Jeff Gifford *Jamie A. Tucker DIRECTED BY Martin Benson HONORARY PRODUCERS CORPORATE PRODUCER Barbara and William Roberts American Airlines Presented by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. A View from the Bridge • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Alfieri ....................................................................................... Hal Landon Jr.* Eddie ........................................................................................ Richard Doyle* Louis .............................................................................................. Sal Viscuso* Mike ............................................................................................ Mark Brown* Catherine .................................................................................... Daisy Eagan* Beatrice ................................................................................ Elizabeth Ruscio* Marco .................................................................................... Anthony Cistaro* Rodolpho .......................................................................... -

First Amendment Under Attack: a Defense of the People's Right to Know Elmer W

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 42 | Issue 6 Article 5 1-1-1967 First Amendment under Attack: A Defense of the People's Right to Know Elmer W. Lower Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Elmer W. Lower, First Amendment under Attack: A Defense of the People's Right to Know, 42 Notre Dame L. Rev. 896 (1967). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol42/iss6/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FIRST AMENDMENT UNDER ATTACK: A DEFENSE OF THE PEOPLE'S RIGHT TO KNOW* Elmer W. Lower** It was just after two in the morning in East New York, a tough part of Brooklyn. Leon Negri, sixty-one-year-old watchman, and his wife had attended a family party and stood waiting on the corner for a homeward-bound bus. As they waited, a group of youths were making a clamor half a block away. One of the youths left the group, walked the half block, and grabbed for Flora Negri's purse. At that moment, the bus pulled up, and as Flora's husband pounded on the door for help, the youth pulled out a 22-caliber revolver and shot him in the back. The husband collapsed on the bus floor, dead. The youth fled. All this was duly reported by the New York news media.' The next day a seventeen-year-old boy was booked on a charge of killing Mr. -

Congressional Record- Senate

10310 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- SENATE May 16 an agreement that will serve as a valuable STATE OF NEw YoRK, We deeply appreciate the confidence in precedent in safeguarding the public health EXECUTIVE CHAMBER, New York State evidenced by the expres and safety and in introducing into the regu Albany, Apr. 26, 1960. sion of the Commission's hope, contained latory control of atomic activities the com Hon. JoHN A. McCoNE, in Acting Chairman Floberg's letter to me petence and high regard for the public in Chairman, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, of April 12, that we take the lead in reach terest which exists among State authorities. Washington, D.C. ing an agreement with the Commission and We look upon this new step as a milestone DEAR JoHN: I am inclosing a copy of a thereby serve as an example for other States in the development and control of atomic letter I have sent to the President advis to follow. We shall make every effort to energy, and we shall do aJ.l that we can to ing that New York State will submit its com achieve this desirable objective. insure its success. · · ments on the Commission's criteria for With best wishes. Sincerely, proposed Federal-State atomic energy agree Sincerely, NELSON A. RocKEFELLER. ments to you within the next few weeks. NELSON A. RocKEFELLER. proval for mergers and consolidations of in embodied in the five freedoms-speech, SENATE sured banks; religion, press, assembly, and petition S. 1328. An act for the relief of Parker E. sanctified by the Bill of Rights adopted MoNDAY, MAY 16, 1960 Dragoo; S. -

(XXXVIII:10) Michael Cimino: the DEER HUNTER (1978, 183 Min.) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

April 9, 2019 (XXXVIII:10) Michael Cimino: THE DEER HUNTER (1978, 183 min.) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. DIRECTOR Michael Cimino WRITING Michael Cimino, Deric Washburn, Louis Garfinkle, and Quinn K. Redeker developed the story, and Deric Washburn wrote the screenplay. PRODUCED BY Michael Cimino, Michael Deeley, John Peverall, and Barry Spikings CINEMATOGRAPHY Vilmos Zsigmond MUSIC Stanley Myers EDITING Peter Zinner At the 1979 Academy Awards, the film won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Film Editing, Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and Best Sound, and it was nominated for Oscars for Best Actor in a Leading Role, Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Best Writing, and Best Cinematography. CAST Robert De Niro...Michael John Cazale...Stan John Savage...Steven Christopher Walken...Nick was the first of a “spate of pictures. .articulat[ing] the effect on Meryl Streep...Linda the American psyche of the Vietnam war” (The Guardian). George Dzundza...John Cimino won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Directing and was Chuck Aspegren...Axel nominated for Best Writing for The Deer Hunter. The film was Shirley Stoler...Steven's Mother such an artistic and critical accomplishment that he was given Rutanya Alda...Angela carte blanche from United Artists to make his next film, the Pierre Segui...Julien western Heaven’s Gate* (1980). This decision was a serious Mady Kaplan...Axel's Girl blow to Cimino’s directorial career, and it brought about the Amy Wright... Bridesmaid downfall of United Artists, forcing its sale to MGM in 1981 (The Mary Ann Haenel...Stan's Girl Guardian). -

Securities Law in the Sixties: the Supreme Court, the Second Circuit, and the Triumph of Purpose Over Text

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Law & Economics Working Papers 2-7-2018 Securities Law in the Sixties: The Supreme Court, the Second Circuit, and the Triumph of Purpose over Text Adam C. Pritchard University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Robert B. Thompson Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/law_econ_current Part of the Law and Economics Commons Working Paper Citation Pritchard, Adam C. and Thompson, Robert B., "Securities Law in the Sixties: The Supreme Court, the Second Circuit, and the Triumph of Purpose over Text" (2018). Law & Economics Working Papers. 150. https://repository.law.umich.edu/law_econ_current/150 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law & Economics Working Papers by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pritchard and Thompson: Securities Law in the Sixties: The Supreme Court, the Second Circuit, and the Triumph of Purpose over Text A.C. Pritchard & Robert B. Thompson* 7 February 2018 ABSTRACT This articles analyzes the Supreme Court’s leading securities cases from 1962 to 1972—Capital Gains, J.I. Case v. Borak, Mills v. Electric Auto‐Lite Co., Bankers Life, and Affiliated Ute—relying not just on the published opinions, but also the justices’ internal letters, memos, and conference notes. The Sixties Court did not simply apply the text as enacted by Congress, but instead invoked the securities laws’ purposes as a guide to interpretation. -

A TALE of TWO HANDS: One Clapping; One Not

A TALE OF TWO HANDS: One Clapping; One Not Burt Neuborne* My thanks to the editors of the Arizona State Law Journal for organizing this symposium celebrating the 100th anniversary of Judge Learned Hand’s brilliant and courageous, if unsuccessful, effort in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten1 to slow down the repressive train that was running amok over Americans who vigorously spoke out against America’s entry into World War I. While many have chronicled the major Supreme Court cases from Schenck to Gitlow failing to protect free speech during and after World War I,2 they usually don’t go beneath the surface of the Supreme Court to plumb the massive wave of repression that swept the nation in the summer and fall of 1917, fanned by jingoism, fear of immigrants, war fever, fear of communism, and President Woodrow Wilson’s streak of fanaticism.3 Convinced that he was doing God’s work in committing the nation to a war to make the world safe for democracy, Wilson, a baffling figure who was an appalling racist, an economic reformer, an idealistic internationalist, and the first President to appoint a Jew to the Supreme Court,4 had no qualms about * Norman Dorsen Professor in Civil Liberties, New York University School of Law. I’m sorry that we lost my longtime friend and colleague, Norman Dorsen, who died on July 1, 2017, before he had a chance to join in the festivities. Much of what I say in this essay emerged from almost fifty years of conversations with Norman. We would have enjoyed writing this one together.